User:Thijshijsijsjss/Gossamery: Difference between revisions

(Transclude (currently non-existent) entry for imaginary quartets) |

m (Fix link and transclusion (for future copy paste reasons)) |

||

| (2 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 25: | Line 25: | ||

==[[User:Thijshijsijsjss/Gossamery/Exercises_in_Style|Exerices in Style]]== | ==[[User:Thijshijsijsjss/Gossamery/Exercises_in_Style|Exerices in Style]]== | ||

{{:User:Thijshijsijsjss/Gossamery/Exercises_in_Style}} | {{:User:Thijshijsijsjss/Gossamery/Exercises_in_Style}} | ||

==[[User:Thijshijsijsjss/Gossamery/Game_Poems|Game Poems: Videogame Design as a Lyric Practise]]== | |||

{{:User:Thijshijsijsjss/Gossamery/Game_Poems}} | |||

==[[/Profielen_Letter_Joseph|Profielen ingezonden brief: Laptops drie jaar gebruiken is niet genoeg!]]== | ==[[/Profielen_Letter_Joseph|Profielen ingezonden brief: Laptops drie jaar gebruiken is niet genoeg!]]== | ||

| Line 40: | Line 43: | ||

==[[User:Thijshijsijsjss/Gossamery/The_New_Media_Reader/Time_Frames|The New Media Reader, chapter 50: Time Frames]]== | ==[[User:Thijshijsijsjss/Gossamery/The_New_Media_Reader/Time_Frames|The New Media Reader, chapter 50: Time Frames]]== | ||

{{:User:Thijshijsijsjss/Gossamery/The_New_Media_Reader/Time_Frames}} | {{:User:Thijshijsijsjss/Gossamery/The_New_Media_Reader/Time_Frames}} | ||

==[[User:Thijshijsijsjss/Gossamery/The_New_Media_Reader/Nonlinearity_and_Literary_Theory|The New Media Reader, chapter 52: Nonlinearity and Literary Theory]]== | |||

{{:User:Thijshijsijsjss/Gossamery/The_New_Media_Reader/Nonlinearity_and_Literary_Theory}} | |||

==[[User:Thijshijsijsjss/Gossamery/The_World_of_Warcraft_Psychogeographical_Association|The World of Warcraft Psychogeographical Association]]== | ==[[User:Thijshijsijsjss/Gossamery/The_World_of_Warcraft_Psychogeographical_Association|The World of Warcraft Psychogeographical Association]]== | ||

Latest revision as of 12:10, 4 August 2024

A gossamery glossary cemetery, parce que 解読 est un cadeau wanneer je het liebst / lebst.

La Musée Bibliotheque

Annotations

16 Case storyies reimagining the practise of layout

- Read: May 2024

- Download it here from the bootleg library. I also have this publication in physical form.

This publication was given to me by Gijs de Heij after the 2024-04-04 Pen Plotting Party at OSP. I started reading it purely on the merit of him having given it to me in relation to this event I was part of, and because it is a pen plotted publication. So far, my explorations with plotters have not included a lot of text. Also, I am still a novice at graphic design. This publication should be exciting on both accounts.

[...] a way to use software as a tool to think with, as location for a dialogie about practise and tools.

The text On the Dataset's ruins[1] poses that it is the dataset that determines the algorithms that needs to process it. Software has an obvious process of naturalisation (Leight Star[2]). This publication's introduction text raises the question: how is our practise shaped (and maybe confined) by the tools we use? Are we, the algorithmic devices processing these tools, predetermined by our preset selection of tools? 16 case stories provides four 'axes of orientation' to develop digital tools. The following is taken from the publication directly:

- Digital Sensitivity: tools that combine digital, programmatic and computational possibilities with the sensitivity of a human designer.

- Process Aware: tools that are history-aware, have a memory and invite reflection and dialogue. Tools that make their processes explicit, make human-machine interactions available for questioning, and ultimately allow us to understand better how we relate to the world around us through software.

- Extended Dimensions: How can we think of layout as a practise of many dimensions, and go beyond the restrictions of a flat plane with horizontal lines and rectangles?

- Engage and disengage: [...] a binary state of digital objects [that] show how fixed and fluid elements might mix and blend into each other.

99 Variations on a Proof

- Obtained: 2024-03-07

- I own this book in physical form; approach me if you're interested to take a look; still looking for a pdf

99 Variations on a Proof (Ording, 2019) is a book presenting the multiplicity and situatedness of mathematical practises through a series of non (non-)proofs for the same problem. These proofs range from traditional (e.g. 6 Axiomatic, 13 Reductio ad Absurdum, 40 Induction) to visual (e.g. 3 Illustrated, 39 Origami) to fictionalized (e.g. 43 Screenplay, 65 Tea). Every proof is accompanied by an explanation that elaborates not only on the proof, but also on the context of it. They provide a glimpse of mathematics not just as the results on paper, but as the human practise of it.

I had been vaguely aware of this book before stumbling upon it in Leeszaal. I have found it to be insightful, poetic, puzzling, touching. It it a powerful, playful representation of a field that, from within, is often archaic and hierarchical. This method might be applied elsewhere, too.

There is a relation to the listmaking exercises we have been doing during SI24 (on the back: 'According to Molière there are many ways to declare love [and] lists five [...]'). Perec's An Attempt at Exhausting a Place in Paris, might have a different feel and goal, but sees similarities at the same time.

In December 2023, I wrote a text by what I like to think of as 'axiomatic writing'. I've had lingering motivation to return to this writing style at some point. Reading axiomatic proofs surrounded by fictional and poetic pieces in this book, has reemphasized its power to me.

|

|

A History of Play in Print: Board Games from the Renaissance to Milton Bradley, Kelli Wood

- Read on 2024-01-30

- Read it here.

Color lithography; combining lithos; Francesco Berni (1526):

He who knows without the use of a compass, that nature, fortune, and skill make up the parts of [~ Primiera ~] And if you look closely part by part There are things there you will not find elsewhere. If you want a hundred thousand cards. Things useful, beautiful, and new. Things to take up in the summer, and the winter. The night and day, when it is sunny and when it rains.”

English translator and poet Charles Cotton wrote The compleat gamester [...] in 1674, which became a hallmark work describing the rules of games for polite British society [...].

The life of men is like the game of dice: If the throw you need does not happen, Then that which has happened through fate, you must correct through skill.

In the 16th century, concerns over such gambling games started to arise. Of course excused for nobility -- '"it [gambling] can be a virtuous act" if it is done in moderation by those who do not undertake it to earn money'

Buoninsegni also situates the role of chance in gambling games as guided by ‘infallible providence of God’ and ‘divine will,’ excusing another problematic aspect of printed games- the act of telling the future [...].

'Fortune Book games', interweaving divinity, chance and play. Wheel of fortune representing player turns. Game of Goose as a metaphor for reincarnation

Other printed game boards of the late 16th century also visually evoke these earlier fortune book games, sharing their structure of a central image surrounded by an outward radiating wheel of symbols and text with directions for the player [...].

the kabalistic number 63, the final space, represented the number of years of human life, and the space of death near the end, which sends the player back to the beginning of the game.

Board game names used to be really uninspiring. The New Game of Honor, The New Game of Human Life. Path racing with vices and virtues. Later used in Milton Bradley's Chackered Game of Life, reproducing Victorian middle class values:

ruin and poverty -> caused by gambling and intemperance wealth and happiness -> caused by industry, honor, and bravery.

In newer games of life, morality slowly being replaced by material goals. Allocation of wealth not solely based on fate anymore, but also by player actions, reflecting American 20th century capitalism. Obligatory John Green video on the history of Monopoly.

(Summarize a bit; talk about eurogames and amerigames; Catan; typical moral themes; link to video games)

Ccru Writings 1997-2003

I was interested to read up on Fiction Theory, after I heard about its connection to modal logic. In particular, to Kripke's application of modal logic to semantics, something I'm vaguely familiar with from previous (intuistionistic) endeavors into the foundations of mathematics.

This is how I stumbled upon the Ccru Writings (1997-2003). Upon looking for some context, it seems to be ununtangleably intertwined with the radicalization of some of its members, Nick Land in particular. (Is this the material I was looking for...?)

The Ccru does not, has not, and will never exist

Reminiscent of Smalfilm, the second song from Spinvis's excellent 2002 debut album.

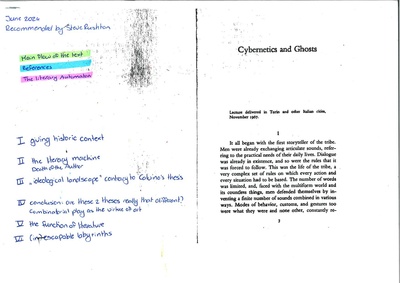

Cybernetics and Ghosts

- Read in June 2024

- Read it here

- Recommended by Steve Rushton

Steve recommended this text to me, after we had a heartfelt introspective conversation. I had come to him feeling stuck. Stuck with the Special Issue, with my PTMoMNBMs, with my reader and with life in general. I have been feeling overwhelmed -- what's new? -- and as a result, haven't found the clarity of mind to create from a place of introspection. This, it seems, is important fuel for my creative process. Looking at my PTMoMNBMs, I felt like this was missing. By nature, I tend to think format-first, rather than content-first. How might these be combined? Looking (by Steve's prompt) at projects I do feel satisfied, even kinship with, I returned to The Hitchhiker's Guide to and Active Archive and User:Thijshijsijsjss/Battles the Pale Grasses of Pink V. These are both examples of projects with a strong 'automated' / 'contrained' formatic identity. These contraints as a format seem to provide a tension with introspection, resulting in fruitful grounds for content. Something, maybe, to be chased. On this bases, Steve recommended the text Cybernetics and Ghosts.

This is a 1967 text (based on a lecture) by Italo Calvino on the literary automaton, the function of literature in society and automation and computation in arts. This text is dense and espansive, but (or: hence) I will try to provide a summary.

Summary of 'Cybernetics and Ghosts'

I. The running thread throughout is one of tribal storytellers. They play a combinatory game with figures (jaguar, toucan, man) and actions (sleep, die, climb). By exploring the permutations, stories emerged. These always contained correspondences or contraries, and they allowed certain relationships among elements, but not others (e.g. prohibition must come before punishment). Propp notes that such tales are all variations of a single tale. Lévi-Strauss notes the mathematical process we can thus apply to anthropological questions. Is this only true of oral narrative traditions, or of literature as a whole? Quickly, the combinatorial play of narrative possibilities goes beyond the level of syntax, grammar and content, to touch upon the relationship of the narrator to the material and to the reader. Writing, Calvino notes, no longer consists in narrating, but in saying one is narrating. 'The psychological person is replaced by a linguistic or even a grammatical person, defined solely by [their] place in the discourse.' He goes on to describe the current world's 'triumph of discontinuity' -- things that once appeared continuous, are now looked upon as discrete. Thought, for example, has gone from a fluid matter to a series of discontinuous states. 'Not even in a lifetime lasting as long as the universe could one manage to make all possible plays.' We are starting to realize the infinitesimal size of these actors. Every analytical process -- every division into parts -- reveals a world even more complicated. In chemistry, history, and liguistics too: the American School led by Chomsky (deep structure of language), the French school of Greimas (structural semantics), the Soviet school headed by Kholmogorov (neo-formatlist), the French Oulipo founded by Queneau. Having said this, the question arrises: will we have a machine capable of replacing the poet and the author? A literary automaton not only capable of 'assembly-line literary production', but of a deep exploration of psychological life. This question is not so interesting for the practical feasibility of it, but rather for the theoretical possibility and the conjectures it inspires. The true literary machine will feel the need to produce disorder, in reaction to its preceding production of order. It will eventually feel unsatisfied with its own traditionalism. It will, at last, be 'the' literature. II. With all written text, various theories on aesthetics maintained it was a matter of inspiration, something intuitive. But even these questions cannot answer the question: how does one arrive at the written page? Calvino states: literature as I knew it was a constant series of attempts to make one word stay put after another by following certain definite rules. Or rules that were neither definite nor definable, derived from the tradition of other writers. And in these operations, the person 'I' splits into a number of different figures: 'I' who is writing. 'I' who is written. An empirical 'I' who looks over the shoulder of the writing 'I' into a mythical 'I' who serves as a model for the 'I' who is written. 'The 'I' of the authos is dissolved in the writing, the so-called personality of the writer exists within the very act of writing.' Thus, an appropriately instructed writing machine would be able to not just produce text, but produce an unmistakable 'personality' or figure of the author. What has been called talent or intuition is nothing more than empirical navigation. Something the literary automaton would be particularly rapid and multithreaded at. Still, literature would continue to be 'a place of priviledge withing the human consciousness'. The work will continue to be born, judged destroyed or constantly renewed on contact with the eye of the reader. What will vanish, is the figure of the author. This gives rise to a more thoughtful prson: one who will know that the author is a machine, and will know how this machine works. III. Calvino then examines a contrary thesis. Did we say literature is entirely involved with the permutation of a limited number of elements and functions in language? But is literature not the continual striving to escape this finite number? To escape from the confines of language? We return to the storyteller, who puts together phrases until something never been said is captured. Myth, then, is the hidden part of every story. The part that is still unexplored, because our words are lacking to enable us to get there. Thus, we need signs and happenings to venture there: rites. Myth is a language vacuum, nourished by silence as well as by words. He then connects this to conscious: isn't the subconscious similar to the myth? Just the region that has not yet been put into words in the conscious? The power of literature lies in in the willingness to give a voice to what has remained unexpressed in the social or individual unconscious. IV. We now make the jump to art in general, by examining puns. The pleasure of puns, says Gombrich, is obtained by following the possibilities of permutations and transformations implicit in language. The juxtaposition of concepts that we have stumbled across by change unexpectedly unleashes a precious idea. The processess of poetry and art are analogous to those of a play on words. Hence, the literary machine can perform all permutations possible, but the poetic result will be the particular effect of one of these permutations on a [person] endowed with a consciousness and an unconsiousness. (An 'empirical and historical [person]') Moreover, this conclusion is reached from the thesis of literature as a means to escape the confines of language. A thesis opposing Calvino's initial stance. Hence, we see that the two routes come together in the end: literature is a combinatorial game that purues the possibilities implicit in its own material, independent of the personality of the [creator], that is invested with an unexposed meaning not patent on the linguistic plane. Meaning that slipped from another level, activating something that on that other level is of great concern to the [creator] or society. V. and VI. In this concluding section, Calvino applies the concepts of combinatorics found within literature to the concept of literature itself. Literature itself is an acting agent, a figure subject to actions. For long periods, literature appears to work in favor of consecration, the confirmation of values, the acceptance of authority. But at a certain moment, something in the mechanism is triggered, and literature gives birth to a movement in the opposite direction (Le due tensiono, Vittorini). So far, literature has been too much of an accomplice of nature. Instead, the true value emerges only when it becomes a critic of the world and our way of looking at the world. Through literature, mankind achieved the critical spirit, and transmitted it to collective thought and culture. Enzensberger writes about 'labyrinthe narratives'. He sketches the image of a world difficult to navigate. Every orientation presupposes a disorientation. Only someone who has experienced bewilderment can free themselves from it. Hence, games of orientation are in fact games of disorientation. The labyrinth is a challenge: if you escape, its power is dissolved, because for whom have traversed the labyrinth, no labyrinth exists. The moment a structure appears as metaphysical, the game loses ists dialectical balance. If literature is metaphysical, it is essentially impenetrable, unescapable, and communication is impossible. It is up to the reader to see to it that literature exerts its critical force, and this can occur independently of the author's intentions.

This is a rich text. Calvino introduces the literary automaton not just as an exercise in producing literature, but as one producing an author as well. Moreover, he seems to suggest the combinatorial ideas applicable within literature can also be applied to the concept and function of literature itself in society.

Fifty-odd years after the conception of this text, literature, arts, technology and society have naturally developed, and one is invited to reflect upon these changes by measuring them against Calvino's ideas and predictions. The increasing dominance of AI in art-discourse might be one obvious manifestation of the automaton. More interesting, however, at least to me, is how the concept of the author has changed. With the internet, social media in particular, the threshold to share creations has become infitesimal. Meanwhile, the pressure to build and maintain a persona online is ever-pressing. The 'I' is split into even more persons, and we're left to wonder if there's any meaning left behind the facade of the current-day 'author'. Calvino hit the mark. Toay, creating doesn't consist of making, but of saying one is making. Our psychological lives are lived by the content machine.

But let me try to find solace in the less bleak interpretations (and consequences) of this text, one that actually excited me quite a bit. Like Calvino, a part of me feels reassured by that which is 'finite, discrete and reduced to a system'. But I, too, often wonder if this is due to some unease with lack of control, or fear of the unknown, or lack of confidence, or what Calvino aptly describes as 'intellectual agoraphobia'. Is this a factor in the dissatisfaction I was feeling, and a trigger for insecurities? It is great that in this text, I have not only been able to find recognition, but also inspiration for how it can be different.

Exerices in Style

- Brought to my attention on 2024-06-26

- Read it here on the wiki

- By Raymond Queneau, translated by Barbara Wright

This text by Raymond Quenaeu presents a short story, a 'banal' and 'ordinary' account of a bus accident, in 99 different ways. Translator Barbara Wright writes that Exercises is 'a profound exploration into the possibilities of language. It is an experiment in the philosophy of language.'

It was mentioned by Steve in the final methods class of my first year at XPUB. It piqued my interest, as I've been reading Oulipo material lately. Moreover, it bears striking similarity in concept to 99 Variations on a Proof. What a surprising connective tissue.

Game Poems: Videogame Design as a Lyric Practise

This entry concerns a parallel between video games and poetry explored by Jordan Magnuson. He gave a Games Now! talk at Aalto University, which was recommended to me by Alessia. I had been peripherally aware of this 'genre' so to say, and it seemed like a natural area to explore after / amidst reading lots of material inspired by the Oulipo. In fact, it is summer break right now, and had been hoping to find some inspiration for a game project. So alas, I admit: this entry's existence isn't intellectually pure, but rather also motivated by the hopes of igniting a spark within me. But is that really intellectually murky? This reader as an excuse for endeavors of curiosity, is that not what I set out to do?

Games Now! lecture

- Watched on: 2024-07-30

- Watch it here on YouTube

Magnuson considers video games not as a subset of games, but rather 'an amorhous cloud of overlapping bits and pieces of lots of different traditions and types of media'. One such medium being poetry. Traditionally, the link between these is in words and language. However, Magnuson argues this excludes many games that are still perceived as 'poetic', even without the use of language. Examples of this include Passage (Jason Rohrer) or Loneliness (Jordan Magnuson). There are also examples of game poems that do use text, e.g. dys4ia (Anna Anthropy, itch.io), though this is not the main focus of this talk. Instead, a framework for game poems is given, 7 tendencies that are often characteristics of such games.

- Game poems are short.

- Game poems juxtapose implied meaning with material meaning.

- Game poems are bound to metaphor and ambiguous imagery.

- Game poems are hyperbolic.

- Game poems are subjective.

- Game poems make use of poetic address.

- Game poems exist in a ritual space, rather than a narrative space.

The Book

- Read on: ...

- Read it here

Profielen ingezonden brief: Laptops drie jaar gebruiken is niet genoeg!

- Read on: 2024-02-28, 2024-03-09

- Read it here (English version)

Joseph sent out a Zulip message linking to a published letter of his. I was curious (1) because Joseph has interesting, passionate takes, and (2) because the title suggest a kind of connection to the current Special Issue (23). Indeed:

Anjo [van Kerckhoven, IT-manager van de WdKA] oppert: ‘Het is onprettig als een apparaat begint te storen wanneer je net een college of presentatie wilt geven. Daarom vervangen we preventief.’

This feminist server manifesto ends with:

[A feminist server t]ries hard not to apologize when she is sometimes not available.

All in all, this manifesto advocates for a seamful technology. Van Kerckhoven's argument raises a question about to what extend we can show seams, without them inhibiting the technology's function so fundamentally that it would be better to not use it anymore. In our SI conversations on seams, we have mainly focussed on 'manageably sized' communities surrounding particular technology. The second bullet in the manifesto reads:

[A feminist server i]s run for and by a community that cares enough for her in order to make her exist

How does this translate to communities that are not formed by or centered around on a technology, but still rely on it one way or the other? Just like with the these seams (?) in movies, there's a factor of a community embracing seams to recognize, acknowledge and appreciate a craft. It is self-reflective in that sense. In some instances, this might require a level of technical savvyness to appreciate, something that should not be a responsibility for any and all people in one of these communities. What value does a seamful approach bring then?

(Note that this is a different discussion from software naturalization and obscolence, as rightfully noted in the letter. These are problems with different seams and different attributions of responsibility.)

After reading this, I feel vindicated for carrying an external keyboard alongside my laptop for the last 4 years.

The Foundations of Literature

- Read on 2024-06-20

- Read it here

- By Raymond Queneau, translated by Harry Mathews

A text by Raymond Queneau that attempts to provide an axiomatic system for a literature, after mathematician David Hilbert's Foundations of Geometry[3].

Mathematically, the presentation is a little naive. An axiom cannot be 'obvious', nor can it be surprising. Even worse, an axiom cannot be a truism. For a truism implies a framework of validity, a system to evaluate a statement. Whereas this system is in fact determined by the axioms. Axioms are the rules set in place, the rules of the game. In this light, Queneau's effort is a worthwhile exercise. It was Hilbert himself who famously said any mathematical mention of points, straigt lines and planes, one could use words such as tables, chairs and tankards (also described in this text's introduction).

Hilbert was perhaps more famous for his mathematical contributions, and cemented himself in history with the 23 problems he presented and published in 1900, the problems that, in his judgement, would shape the mathematics of the new century. The second question concerned the axiomatization of mathematics -- initiated in the 1870s by Cantor. Hilbert was a big believer of an axiom system existing to capture the mathematics commonly accepted at the time (even though he may have already been aware of Russel's paradox). He was never able to accept Gödel's second incompleteness theorem, proving no proof of consistency can be given in an axiomatic system itself. Moreover, he refused Godel's first incompleteness theorem, stating that in any axiomatic system powerful enough to decribe the natural numbers, there will be statements that can neither be proven nor disproven.

This is of concern to the Oulipo as well, who believed in the concreteness of language and a study of it as a scientific object[4]. I can't help but wonder: what would Queneau think of this. Isn't this Foundation of Literature, meant to be a transposition of Hilbert's axioms, subject to this incompleteness, too? Even when we try to capture the object of language and its combinatorial game, is this still not enough? Like Calvino describes in Cybernetics and Ghosts, does this not present language as the inescapable metaphysical labyrith[5]? Or should we be hopeful, that no axiomatic system of language can ever fully capture our necessities for it, and therefore, there will always be new potential?

The Gag of Realism: Nathan for You

- Read on 2024-01-25, 2024-03-23

- Read it here

An essay on Nathan for You S3E5 Smokers Allowed, written by Nathan Fielder's The Curse co-writer Benny Safdie, that I encountered when watching a Thomas Flight video.

Nathan for You is a show for which the driving force is the continuous ambiguity of what is real and what is fake. Media with this ambiguity seems to fascinate me (see also my notes on this episode of 60 Songs that Explain the 90s). This element of intrigue is even more present in Fielder's The Rehearsal, where it is even explicitly acknowledged and used as a narrative device.

In Smokers Allowed, Nathan helps a bar that is supposedly struggling to get customers due to anti-smoking laws. It turns out you can smoke inside such a venue in California if and only if it is part of a theatrical production. So Nathan arranges for two big chairs and gives two tickets away to a play 'Smokers Allowed'. The visitors, unaware that what they're seeing is scripted nor acted, turn out to love the 'show' for its sense of realism and avant-garde nature. Nathan then tries, mistakingly attributing the play's success not to its concept but to its content, to recreate the performance to the T. The scenario is then shown to another audience, yet this time it is completely scripted. Meanwhile, we are meta-observers through the show's airing lens, seeing both plays as results of production, and seeing both audiences with a sense of wider-scoped understanding.

I recall watching this episode, and The Rehearsal alike, thinking: I know this is, to an extent, the magic of production. I know there is design and intent and, ultimately, fakery. But I don't really care, I am willing to commit and to believe. Willing, because even in it's potential 'fakeness', it's telling something that is 'true', that holds meaning.

Of an earlier Nathan for You project, Dumb Starbucks, Safdie notes:

[...] Fielder is not playing it for parody. He even says, “This is no bit or joke, this is a real business I plan to get rich from.” By playing it for realism and not flinching, it’s so much funnier. He created something genuinely fake.

Maybe it is not a question of real versus fake, but rather one of genuinity.

The New Media Reader, chapter 12: The Oulipo

- Read it here

- Recommended by Steve Rushton

The New Media Reader, Edited by Noah Wardrip-Fruin and Nick Montfort, 'collects the texts, videos, and computer programs that chronicle the history and form the foundation of the still-emerging field of new media'. It presents a timeline starting at the 40s with the likes of Borges and Turing, spanning to the 90s.

Chapter 12 is dedicated to the Oulipo, with a selection of six works and a general introduction contextualizing the group. This introduction attempts to shed some light on some of their core ideas, for example:

[T]he Oulipians realized that such a system had the potential to define a new type of computer-mediated textuality, producing custom poems in ways that give the reader an enhanced role in the process of literary creation.

One might wonder how this expands to other fields -- especially now that the technological capabilities much more easily facilitate for interaction -- like film and gaming. In the latter case, there are many examples of games that are 'merely a framework for the players' creation': Garry's Mod, Ultimate Chicken Horse, Super Mario Maker, even Minecraft.

In film, there are choose your own adventure projects, but in my experience so far, they are often stiff and don't realize the full potential of their form. Again, if we return to games, we do see interactive video projects, like Her Story.

Either way, I see this 'enhanced role' as hopeful. In the current landscape of media, one is flooded by content in ways that reduce agency, to a point that one wants agency no longer, just consumption. Maybe this enhancement can be a challenge, a provocation to combat the symptoms of a generation.

[A computer that takes a very large space of possible stories and narrows it down to one] is a potentially powerful story-production method, and yet the conclusion of Clavino's essay argues that the solution of any algorithm, the narrowing of even the most artfully constructed set of combinatory possibilities, cannot create literature. He states that it is the 'clinamen' which alone can make of the text a true work of art. The climanem is the deviation, the error in the system.

This is echoed in Calvino's lecture Cybernetics and Ghosts -- the text read before this one in the chronology of the relation between these specific texts and this specific figure of a reader. This idea resonates with me. Not only in arts, but in life in general I have found many activities to be awkward, frsutrating and painful experiences that I stick to, because I know that sticking to it means eventually finding the 'click', that one connection, or one climanem or however you want to describe it, that lets me find a new meaning within myself. In many ways, this reader (referring not to my person, but to this collection of annotations and thoughts) is such an experience.

The potential that lies within such an understanding of interactive experiences is a recongifuration of the relationship between reader, author, and text. The playful construction within constraints that the Oulipo defines as the role of the author can become an activity extended to readers, who can take part in the interpretation, configuration, and construction of texts.

Reader is a curious word for an 'object' like this. It describes an agent, whether that is the agent 'to be read works', or the agent 'reader' created when interacting with this object. It occurs to me that it is no coincidence, perhaps, that this particular reader is not a noun, but rather an adjective: a suggestion of what this interaction for 'the object reader' might be like for 'the person reader'. A word capturing their connection, maybe.

A Hundred Thousand Billion Poems

According to Jean Lescure [6], Raymond Queneau's A Hundred Thousand Billion Poems (Cent Mille Milliards de poèmes) is 'perhaps the prototypical example of the Oulipian potential'. It presents 10 sonnets -- all not only following the same rhyme scheme, but the same rhyme sounds, too. Allowing the reader to swap any line with another from the same position in another poem, the reader is invited to become part of the process of literary creation.

Online versions (like one by Beverly Charles Rowe [7]) beg the question what role materiality plays in this process. I myself notice my exploration of the potential to be subtly different rearranging paper versus selecting by mouse click.

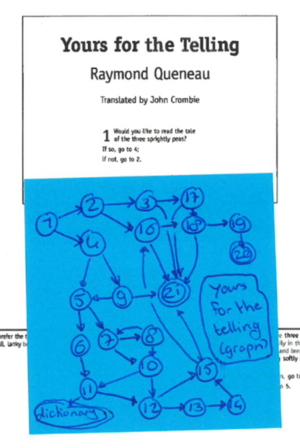

Yours for the Telling

- Read on 2024-06-19

- By Raymond Queneau, translated by John Crombie

A cute, short choose-your-own-adventure-like story that with 21 'nodes' manages to realize many mechanics of the genre: branches, different endings, loops, and directions that let you escape the graph of story nodes all together (in this case by referring you to a dictionary to acquire your own interpretation).

This work was originally published in 1973, preceding the CYOA books made by Edward Packard that started serial publishing in 1976 and book publishing in 1979 [8][9]. Just like these stories, Yours for the Telling doesn't shy away from making the choices explicit, though not diegetic -- contrary to the way this is often done in contemporary video games. However, there is a difference between Queneau's story and those of Packard: in Yours for the Telling, the 'you' addressed in the story is the individual of the reader. There is no seperation between the 'you' reading the story and the 'you' addressed in the story. This in stark contrast to the CYAO books: the addressed 'you' deciding to venture into a dark cave is a 'puppet-you', controlled and existing in the mind of the 'reader-you', but whose existences doesn't fully coinside. (Compare this to Calvino's Cybernetics and Ghosts, section II[10])

Just like with A Hundred Thousand Billion Poems, there's the question how the form factor impacts the experience. I have noticed that digital choose your own adventures (literal ones, or more videogame-y ones where the options are implicit or the option space invisible) often don't convey this feeling of sprawling potential to me. In a paradoxical manner, being able to capture the bounds of the story, its graphical finality, makes me feel the optionality and interconnectivity more.

A Brief History of the Oulipo

- Read on 2024-06-20

- By Jean Lescure

This text presents an overview of some Oulipo history and by doing so, naturally has connections to many other texts. For example, some touched upon ideas about inspiration and the definition of literature are explored in more depth in Cybernetics and Ghosts, by Oulipo's Calvino.

More interesting, maybe, is a connection present through all work by the Oulipo I have met thus far: a connection to the concept op play. In this text, Raymond Queneau's Odile is quoted:

The really inspired person is never inspired, but always inspired.

With this statement, the objectivity of literature is implied (according to Lescure). This objectivity made it possible to explore literature through the modes of manipulation, as one would explore the field of mathematics. This exploration is often game-like. In fact, it's even referred to as 'games of language' or 'combinatorial play'. In Homo Ludens, Huizinga declares the first characteristic of play all play is a volunatry activity. We see this sentiment reflected in the play of language, by Queneau's words:

The only literature is voluntary literature.

For a Potential Analysis of Combinatory Literature

Computer and Writer: The Centre Pompidou Experiment

- Read on 2024-07-08

- By Paul Fournel

A short text describing early applications of computers (CLIs) in literature. Fournel creates two categories, the first one being so naturalized now that it is almost surprising to see it written: aided reading. In this case, it isn't so much about providing accessibility through technology, but rather that the physical action to consume certain texts can be awkward, tedious or take away from it's contents. A Hundred Thousand Billion Poems is given as an example: the strips of text are too tedious to manipulate. Instead, a computer could present you the different poems tidily. Another example given is Yours for the Telling, with the motivation that the game dominates the reading of the text itself. I can see how these examples have some truth to them, but as stated in other entries, to me the form is so much of the message that it's difficult to translate the experiences in more streamlined ones without losing their defining merit.

The second category is aided creation and concerns the involvement of the computer between author and created work. Multiple flavors are described, one of which being: author > computer > reader > computer . work. The author provides some 'building blocks' for the reader, and they 'build' something that then becomes the work (with computational involvement along the way). This sounds not only very xpubian, but also has untapped potential in many fields other than literature (e.g. Print-and-Play Games). In Cybernetics and ghosts, Calvino describes how the 'I' is split when writing. This flavor of aided creation also suggests a split of the work itself: an imagined work as conjured by the author, an intermediate work as shown to the reader, a 'completed' work as handed off by the computer, and many a potential work for different combinatorial outcomes.

Although aided reading and creation have evolved and naturalized a lot over the almost 40 years since the publication of this text in 1986, I don't know if these various applications have so much concerned themselves with literature. Or rather, if contemporary literature wants to concern itself with them. In fact, with recent AI developments, aided creation is getting a negative connotation. But what about all those aids we like to ignore? Is a thesaurus not a combinatorial writing aid? Is my writing not fundamentally guided by the interfaces in which I write?

Prose and Anticombinatorics

- Read on 2024-08-01

This text by Italo Calvino is a direct follow up to Paul Fournel's The Centre Pompidou Experiment, both in The New Media Reader as in their original publications. The former explicitly references the latter in the introductory words. In contrast to Fournel's text, that investigates the use of a computer as a literary aid in realizing combinatorial potential, Calvino's focusses on the anticombinatorial character of the computer aid that from a large number of possibilities selects those few realizations compliant with specific constraints.

The text starts with an exerpt from yet another text by Calvino, a short story in the making, in which a book is report is found that describes twelve sinister events. The task of the story's protagonist is to find the people who were guilty of and were victim to these acts. Calvino then goes on the descirbe different categorizations of the acts, and gives sets of constraints that might acts as deduction rules. As an example: an act of suicide by character A might not preceed an act of blackmailing by A, as A is assumed to by dead by the time of the second act.

With these sets of constraints, a computer aid can produce scenario's possible. This, Calvino argues, is not an act of replacing the creative act of the author. Instead, it liberates them from the chains of combinatorial search, allowing them to focus on the 'clinamen' that with which they can lift the text to a work of art.

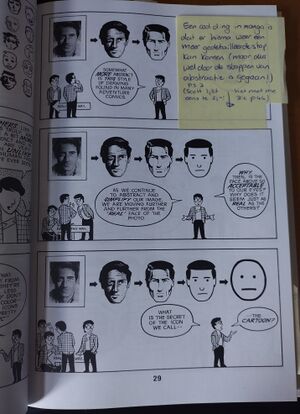

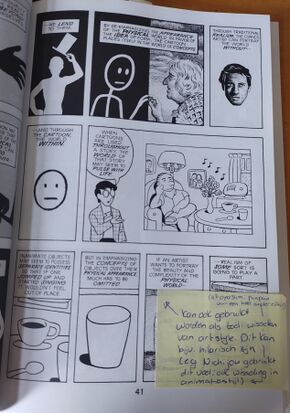

The New Media Reader, chapter 50: Time Frames

- Read in March 2023 in the context of Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art, reread June 2024

- Read it here

Chapter 50 of The New Media Reader covers the fourth chapter of Scott McCloud's book Understanding Comics: the Invisible Art. This book takes a closer look at comics as a 'sequential art', one of 'a deliberate sequence of juxtaposed pictorial and other images'. I read it unknowlingly read half a year before starting at XPUB, and was surprised to encounter it again. As the introction states:

Looking to Understanding comics can provoke new media insight, but it's certainly not the case that all of McCloud's techniques can be easily dragged and dropped into the digital realm. What McCloud's work nevertheless chows is that new forms, even those that have not been studies seriously for centuries or even decades, do indeed have certain conventions and rules, and that if the form being studied is considered with care and thought, these rules can be determined (...)

Notably, this deconstruction of the comic is itself presented as a comic (see example). This particular chapter of 'Understanding Comics' is concerned with the question how time can be represented in an art that is purely spatial (though there is an element of time in reading).

On March 8th, 2024, I had a conversation with Senka regarding comics. We discussed this book, and as a response Senka recommended Here by Richard Mcguire.

I asked the friend from whom I had borrowed Understanding Comics: the Invisible Art at the time to send some of my annotations:

|

|

|

The New Media Reader, chapter 52: Nonlinearity and Literary Theory

- Read on: July 2024

- Read it physically in the studio, or on the bootleg library (TODO), or with my annotations (TODO)

This 1994 essay by Espen J. Aarseth outlines a theory of nonlinear texts and places this in the discourse of contemporary literary theory. I stumbled upon it in The New Media Reader, after reading the preceding chapters 12 and 50. By the merit of its placement in the book, that follows a chronological timeline, the alluring title, and Aarseth's name being connected to ludology, my interest was piqued. It is a dense text. Therefore, this entry will start with an attempt of a (subjective) (digestive) summary, after which more personal reflections are explored.

Follow ups to explore:

- Cybertext: Perspectives on Ergodic Literature (Espen J. Aarseth) (monoskop link)

Summary of 'Nonlinearity and Literary Theory'

Introduction

A nonlinear text is an object of verbal communication that is not simply one fixed sequence of letters, wors and sentences, but one in which the words or sequence of words maay differ from reading to reading because of the shape, conventions or mechanisms of the text. In particular, this refers to the form of the text, not to any fictional meaning they might hold. For example: nonlinearity and nonchronologicality are not the same.

I want to bring forward a passage from the next section, as it reflects on this definiction and introduces terms fundamental to this essay. Aarseth notes that his use of the word "text" might clash with some textual theory that regard the text as a semantic network of symbolic relations, loosely attached to the notion of the literary work. He states having no intention to challenge this, but instead wants to shed light on two perspectives on text. These aspects follow different rules, but are interdependent.

1) Informative: the text as a technical, historical and social object. This brings rise to a fundemental characteristic of a text: in addition to the visible words and spaces (which we might call "script"), a text includes a practise, a structure or ritual of use. We can compare this to the concept of a genre, except that genre is seen prior to the text, contrary to this choreographic practise.

2) Interpretable: the text as is individually received and understood. Here, Aarseth highlights a "flaw" in this definition: it is open to interference from the interpretable level. What if the text insists on its nonlinearity? Or what if it gives instructions and cancels them later on? Or tells you to skip over some instructions, for they might be contaminated by subversive directions? The linear text can flirt with nonlinearity, but the nonlinear text cannot lie and pretend to be linear.

Behind the Lines: What is a Text, Anyway?

We must rethink the concept op textuality to allow for both linear and non-linear texts. "The text" brings about a set of metaphysics, the 3 main ones being:

1) Reading: a text is what you read, the words and phrases you see and the meanings they produce in your head

2) Writing: a text is a message, imbued with the values and intentoins of a specific writer / genre / culture

3) A text is a fixed sequence of constituents that cannot change, although its interpretations might

Aarseth opposes these notions, arguing that nonlinear literature shows us a textuality different from our readings, more fundamental than our messages and, through evolving rituals and technologies or use and distribution, subject to many types of change. The remainder of the section is dedicated to a sequence of questions, examples and ontological edge cases to provoke examination of the question of a text's metaphysics, in an effort to give a concluding definition that allows us to include nonlinear texts.

What elements belong to a text? For example: does our interpretation not start already before the first word of the script, with the author's name? Historically, author's have been aware of this, play with it (perhaps out of necessity), e.g. with pseudonymns. This suggests: the name belongs to the text, the person of the writer does not.

This begs the quesion: in what sense can there exist a script independent of text? Imagine a book from which the middle 10 pages are 'missing'. We are quick to assume the existence of some 'ideal book', deeming it more real than our copy. We do this out of disrespect for he copy, as it seems to misrepresent the 'real' text. Even though we observe a stable version, we prefer the imagined integrity of the metaphysical object. But what if the 'flaws' interfere so deeply with our sense of reception that they 'steal the show'? Aarseth makes an argument here that I do not follow, paradoxically concluding that some texts are metaphysical, some are not. Another option, he states, is to abandon the concept of the transcedental text-behind-the-text altogether.

We are presented another example (Zardos ***), one in which acts of a film are, unbeknownst to the audience, shown in an order different from the creators' intentions. Again, we can ask ourself if a new film is created. Aarseth answers: no, because they are both based on the same material potential. In this sense, a text is a limited language in which all the parts are known, but the full potential of their combination is not. There are many scales of change in a text's metamorphosis, some of which we might accept as authentic new works, others not (according to the cultural legitimacy of their method of construction, to new policital symbolism, ...). Textual integrity is a cultural construct. More importantly: so is our notion of what constitutes the text itself. A text contains within it its potential interpretability, too. In fact, a text is not what we may read out of it, nor is it what someone once wrote into it. It is a potential that can be realized only partially and only through its script. Furthermore, texts are like electrons: they can never be experienced directly, only by signs of behavior. They are processes impossible to terminate and reduce. This perspective allows us to include nonlinear texts, that often have no author or reader in the traditional sense.

A Typology of Nonlinear Textuality

Aarseth points out that this effort of formalizing nonlinearity is grounded in mathematics, in particular: topology, the study of properties of a geometric object that are perserved under continuous deformation. An attempt at a textonomical analogy is presented: the study of ways in which the various sections of text are connected, disregarding the physical properties of the channel (paper, etc). (Note that by having such a direct transposition from geometry to textonomy, the author claims to preserve formalism. I disagree.)

Textual topology describes the formal structures that govern the sequence and accessibility of the script. For a text to be described topologically, it must consist of smaller unit and connections between them. The units are called textons. An unbroken sequence of textons as they are projected by the text is a scripton. The connections are traversal functions, of which there exists an infinite set (**). The author makes an attempt to describe some variates that together define a multi-dimensional space into which the functions can be plotted. The variates are as follows:

* Topology: distinguished between linear and nonlinear texts, where nonlinear texts are those works that do not present scriptons in a fixed sequence (whether temporal or spatial). INstead, through cybernetic agency, an arbitrary sequence emerges.

* Dynamics: there are texts that are static (with constant scriptons) and dynamic (the contents of scriptons may change).

* Determinability: a text can be determinate (adjacent scriptons are always the the same) and indeterminate (otherwise).

* Transiency: a text can be transcient (the passing of a user's time causes scriptons to appear), or intransient (otherwise). If the transciency is real time, it is synchronous. If it's arbitrary, it is asynchronous.

* Maneauverability: describes the agency of traversal. Random access < links with explicit access < hidden links < conditional or complex links < completely controlled access.

* User-functionality: besides the interprative function of thte usuer, the use of nonlinear texts might be described by 4 feedback functions:

* explorative function: in which the user decides which 'path' to take

* role playing function: in which the user assumes strategic responsibility for a 'character' in a 'world'

* configurative function: in which textons and / or traversal functions are in part chosen and / or designed by the user

* poetic function: in which the user's actions, dialogue, or design are aesthetically motivated

(Curiously, these variates are described not as continuous, as the previous claim of infinite functions (**) would lead to believe)

The introduced traversal space is illustrated with an example: Agrippa: A Book of the Dead, a story project at a set pace that would encrypt itself after one showing, rendering it unreadable. If is linearity flirting with nonlinearity through the difference between its used and unused copies. It exposes the inherent instability of the metaphysical concept of 'the text itself': it becomes non-linear only if we choose to accept the 'text-behnid-the-text' as more real thatn the physical copy.

Finally, 4 categories / degrees of nonlinearity are presented:

1) the simple nonlinear text, whose textons are totally static, open and explorable by the user.

2) the discontinuous nonlinear text (hypertext) which may be traversed by 'jumps' (explicit links) between textons.

3) the determinate 'cybertext', in which the behaviour of textons is predictable but conditional and with the element of role playing.

4) the indeterminate cybertext in which textons are dynamic and unpredictable.

The following sections are a discussion of each of these categories.

The Readerless Text

Perhaps the simplest way to achieve nonlinearity is with 'forking paths'. A decision between paths, entirely up to the user, produces an ambiguity different from a phrase's usual poetic (double) meaning, because there seem to be two different versions, neither of which can exist alongside the other, and both obviously different from the text itself. Forking scripts are like optical illusions, we can first imagine one, then another, but never both at the same time. When one looks at the whole of a nonlinear text, one cannot read it. And when we read it, one cannot see the whole text. Somethin has come between us and the text, and that is ourselves trying to read. This self-consioucness forces us to take responsibility for what we read and to accept that it can bever be the text itself.

The presence of the reader is further investigated with two examples of ancient nonlinear texts: wall paintings, read in accordance with the architectural layout of a temple, and Book of Changes. These seem to reject the presence of a traditional reader. Active or passive, the reader is always assumed to be a receiver, constructing meaning only. It can be argued that the same holds true for nonlinear texts: once the novelty has faded, it's back to layed back consuming. However, this counterpoint ignores that (beyond trivial) understanding of a nonlinear text can never be a consummate understanding, because the realization of its script (and not just its meaning) belongs to the individual user, who is acutely aware of their own constructive participation. As alluded to in the paragraph above, the object can only be glimpsed and guessed at. It is this frustrating attempt to harmonize contradictory scriptons from the same text that define the ritual of a nonlinear text. Importantly, a ritual might relief the user of not reading every combinatorial possibility.

Similar to the question of the reader, there is a question of authorship for combinatorial products of a nonlinear text. Queneau's Cent Mille Milliears de Poemes is compared this to the earlier example of Zardos (***). Aarseth concludes that in the latter's case, he rejected his reading as it told him he was not a real reader, since he was not reading the real text. This shock of finding yourself not to be a reader can, Aarseth argues, only (and only accidentally) happen with linear texts, because that is the only text in which the metaphysics of a real reader has any credibility and the only text in which the reader can exist as a reducible, accountable figure.

Hypertext Is Not What You (May) Think

Hypertext is a direct connection rom one position in a text to another. This text is only concerned with hypertext as a this general concept, not two other interpretations that make this a noisy field of study: specific implementations as hypertext systems, or texts within such systems.

Hypertext's main feature is discontinuity. To ease the situation, they often offer additional features (overviews, index views, ...). As we would still consider 'the same' text without such add-ons a hypertext, and as they tend to fundamentally impact the reading ritual, it is hard to consider the work with and without the add-ons as 'the same'.

The remainer of the section is dedicated to discussing the example Afternoon, a story and some more frustrations the author seems to have with misconceptions in hypertext literary discourse. He makes a note, also, that in his mind paper and digital are not two axes in this model, its just that there happen to be many more electronic hypertexts.

Death and Cybernetics in the Ever-ending Text

"A cybertext is a self-chaning text in which scriptons and traversal functions are controlledby an immanent cybernetic agent, either mechanical or human." Two historic examples are the root of computer-mediated cybertexts: Eliza and Adventure. The former was an early AI 'chatbot' playing a psychotherapist. The latter is a text adventure that went on to inspire the likes of Zork, in which the user controls a 'you', role-playing through a narrative. Aarseth notes that death in the cybertext is curious. Instead of signifying closure, 'cyberdeath' instead signifies a sort of reincarnation that implies a new beginning. This clearly distinguishes separate entities of 'user', 'main character' and 'narratee'.

There are two outcomes of a cybertext:

* Either it is successful ('the user wins'). This isn't as satisfying as a traditional text, as the 'you' is left behind and the same build-up and release of tension cannot be provided. It leads to peripety, not catharsis.

* Or it is unsuccessful (the game is not solved). Again, the you is abandoned.

Aarseth concludes that if the absent structure of narrative is the key problem in literary hypertext, in determinate cybertext the abest structure is the plot. In cybertext, the plot is not determined by the story, but instead is hidden itself, to be determined by user actions. Then found ,it does not produce anything interesting.

"The Lingo of the Cable": Travels in Cybertextuality

The Limits of Fiction

The Rhetoric of Nonlinearity

The corruption of the Critic

Problems of "Textual Anthropology"

The World of Warcraft Psychogeographical Association

- Read about it here

- Explored on 2024-06-12

- Recommendation by Lídia Pereira

Angela Washko (wikipedia) is a feminist media artist. This project, based on the Situationist Derivé, 'looks at the virtual physical environment inside WoW and its impact on the emotions and decisions making of the players inside it'.

This is a very powerful notion. I remember drifting like this by myself or with friends, for example in Minecraft (shoot an arrow, walk to your arrow), Stardew Valley (interning with Harvey), or Zelda (I'm a bokoblin now). Not only can it be a comforting and social experience, it can also change your POV in a game and provide agency over how you interact with and navigate through a set environment. I can imagine how this is amplified in an MMO game such as World of Warcraft.

It was recommended to me by Lídia after expressing my disillusion with the game (development) industry.

It sees obvious connections with SI24 as a whole, and certainly with my individual research into the tools video games provide to aid navigation in new environments, and how we might apply them to the physical world.

Also reminiscent of Senka's and Lorenzo's SI22 Project Byte Noise: Sound you see me, Sound you don't

Lots of follow-up references to look into:

Volumetric Regimes

Exploring a new umbrella of literature is a concious effort. I've been trying to look for some work in the intersection of the academic, scientific texts I would read at M/CS and GMT, and sources I'm exposed to at xpub. I found Volumetric Regimes through Stephen's readings list, where Manetta's name caught my eye.

Volumetric Regimes emerges from Possible Bodies, a collaborative, multi-local and polyphonic project situated on the intersection of artistic and academic research, developing alongside an inventory of cases through writing, workshops, visual essays and performances.

The So-called Lookalike

We’re working with a self-hosted MediaWiki platform, a wiki in short, that we as editors and designer can use to edit and structure the materials. From this wiki, we download and reformat everything into a single webpage, which becomes the main document that will be styled and turned into a layout using CSS3 paged media standards. We use the Javascript library Paged.js to paginate this layout in the browser and render it as a PDF. The designer and editors both have access to this rendering process, which allows us to approach the editing and design as one continuous process.

Very much applicable to our work in xpub so far. In particular conversations we've had with Steve concerning the Wordhole Glossary.

Also reminds me that I'm -- aside from being passively interested in web-to-print -- intrigued by print-to-web exploration.

[...] the assumptions of optimisation, agility and efficacy as editorial values [...]

The curious dynamic of editor and designer.

I decided to write you a letter as a way to reflect on this strangeness [...]

In the 3 months I have been able to wikify myself -- and read others' wikifications -- I've come to find it as a very honest medium. But my relationship with it is ever evolving, and I feel a tug of war between this honesty and some kind of curated abstraction. Sometimes I need a reminder that honesty in itself is a valuable and worthy medium.

Film

Citizen Kane (trailer)

- Watched: 2024-03-29

- Watch it here on Wikipedia or on this page -->

In light of the upcoming T2 assessments and my role in the SI23 launch event (e.g. this and this), and amidst my evolving practises in and around XPUB, the I've been thinking more and more about documentation. Non-reactionary documentation, the connection between documentation and invisible labour, fictionalization in documentation, documentation as a communicative practise. The list goes on.

Orson Welles's work has already shown his influence on me in last trimester's The Hitchhiker's Guide to an Active Archive, taken inspiration from War of the Worlds (1938). Researching documenting practises, I once again stumble upon Welles, this time for Citizin Kane. Instead of showing footage from the story, this films trailer is a 4 minute documentary that shines light on its production. How hopeful, documentation as a tool for engagement, as promotional material even.

The Institute

- Watched: 2024-04-25

- Watch it here

The Institute is a 2012 documentary directed by Spencer McCall on the alternate reality 'Game of Nonchalance' initiated by Jell HHull that was ran from 2008 to 2011 in San Fransisco. This game featured a story centering around the concept of 'socio-reengineering', and focussed on shifting a the participants' perspectives on the everyday cityscape with a 'hidden-in-plain-sight wonderland'. The documentary is told as a retrospective, combining interviews from participants and creators with archival footage and new reconstructions. In particular, just like the game's ambiguous veracity, the film is created in such a way that the viewer can question how truthful its contents are. In fact, not having been part of this experience, the whole documentary could be a fabricated story.

This documentary was shared by Louisa as an extension to what we had been discussing during the SI24 prototyping classes. SI24 (on loitering and other forms of in-situ computation) focusses on activating the city, challenges our perception of our environment, and tries to critically reflect on the ways urban and social infrastructures influence each other. This very much resonates with The Institute. In my personal practise, I am very interested in bringing interaction to static media, which is also much involved with changing perspective. Also using gaming and narrative devices.

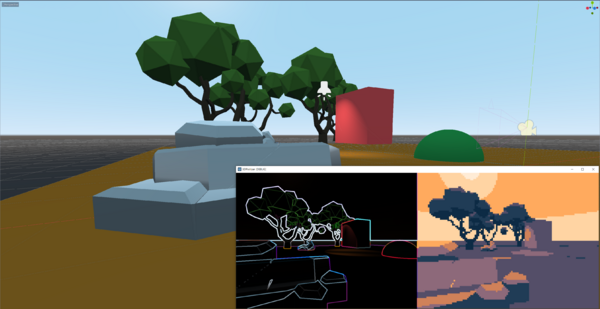

One particularly exciting technique that was briefly shown in the documentary, was using a flyer / postcard to overlay with the city, highlighting a certain buyilding (see photo, compare to Viewfinder). This has the potential more much more applications, e.g. providing an alternative view on the postcard. I have been playing around with this idea for a while, for example in a game prototype I made that uses different shaders to reveal different parts of a landscape (see below).

In the 2024-05-07 Prototyping class, in which we made an small alternate reality game in a single day, I explored this technique with Michel.

Relevant links:

- Wikipedia pages on The Jejune Institute and the documentary

- The Letterboxd page

- Rosa shared a link to this HKU 2008 graduation project in response to The institute

- Louisa shared a link to this project in response to Rosa's link.

Games

Imaginary Quartets

Quartets is a classic card game in which every player is dealt a number of cards, each unique and belonging to a 'quartet', a category of 4 cards. Every turn, the active player A can ask another player B for a specific card with the only conditions being (1) that A doesn't have the card in question themselves, and (2) A has at least one card from the quartet of the card in question. If B has the card, A takes another turn (and they can ask another player then B for a card, if they so want to). If A has a quartet with the newly acquired card, A shouts 'Quartet!' really loudly and reveals the newly formed quartet. In this case, it is B's turn. If B does not have the card, it is B's turn. (Sometimes, A will be allowed to draw a card from a blind deck in this case. But this is neither here nor there for this entry)

Imaginary quartets, then, is the classic game of quartets but without actual cards. Every player is dealt 4 imaginary cards at the start of the game, and there are as many quartets as there are players participating. The game plays similarly, with one crucial difference: the cards are not known beforehand. An example:

A game is played with 3 players, A, B and C. A is the starting player. A must ask for a card. They ask B: Say B, would you happen to have the card XPUB in the category PZI programs? With this action, A creates 5 facts: * There is a card XPUB. * There is a category PZI programs. * The card XPUB belongs to the category PZI Programs, and the category PZI Programs contains a card XPUB. * A does not have the card XPUB of the category PZI Programs. * A does have another, yet to be named card in the category PZI Programs. Now, B has a choice between two replies: (1) Sorry, A, I do not have this card. (2) Wow, A, I do have this card, how did you know? In scenario (1), B creates 2 facts: * B does not have the card XPUB. * C has the card XPUB (based on the earlier information created by A's request). Both A and B have 4 cards in hand still. It is B's turn. In scenario (2), B creates another fact: * B did have the card XPUB, but now A does. B is left with 3 cards in hand, A with 5. It is A's turn.

The fun of this game, of course, is in living out your deepest trickster god fantasies, using your powers of creation against other players, sowing confusion and reaping with outwitted deception. Unlike classic quartets, you can decide for yourself if you want to have a card or not. The decision to create a new category can cause massive, hard to foresee ripples in the game. Players can force cards into other players hands (like in the example). Moreover, there is no constraint on the cards and categories created. For example: in the same game as above, there can be cards mango and XBUP part of the category PZI Programs. Moreover, there can be a category XPUB in the same game! This quick and often deliberate confusion, combined with the rapid creation of many pieces of information that should all be contained in one's mortal mind, makes imaginary quartets a game for which I can seldomly find players...

But! In my experience, this creational ability works as a powerful mechanic. Not just as a tool to outsmart others in an overly complex game, but also as a method of suggestion. Creating with one statement not just the contents of the statement, but a whole ripple effect of potential to explore. It is a tool that is applied (and exploited) often in games, film and literature alike. For example, the relic 'Tiny Chest' from the roguelike deckbuilder Slay the Spire mentions 'The Architect'. I can confidentally say no 'The Architect' appears in the game. Still, the suggestion that there is such a character is enticing, the mere suggestion creates lore more mysterious and deep than would ever be possible with explicit exposition.

(There's more to say here, but for now, I'll just leave it at the suggested potential of the hinted but unwritted ripples)

Podcasts

Without much conscious effort, I've found myself listening to podcast increasingly frequently over the past few years. I will use this space to make some notes and gather some references for those podcast moments that I have found relevant to the course, or to other wikified discourse.

60 Songs That Explain the 90s

In the ever droughtful search for podcasts, I stumbled upon 60 Songs That Explain the 90s.

108: Portishead, Glory Box

- Listened to on 2024-02-15

- Listen to it here

To try out this podcast, I decided to listen to the episode on Dummy semi randomly. Portishead has made some really great music, naturally, and they reside in an area of music history that I'm familiar with, but not super deep into. It is a rich area tough, so I thought this would be a good one to try out. In short: I was very positively surprised!

A meandering opening is held together by an anecdote of the narrator: while attending Portishead's 1997 concert in the Roseland Ballroom (NYC), they got so annoyed with a cheering crowdmember, that they beat them up using the saladbar nearby. The anecdote is in and out of focus during this 30 minute introduction, setting the stage of the time with related acts, the personal experiences of the narrator, and their relationship with Portishead's music. We are fed little audo snippets of the event, accompanying little snippets of the anecdote. We learn that the narrator was never there. But still, they were there and they beat up this audience member. It sounds gruesome, but it is told is such a caring manner. More and more, we learn that this all just a fiction. And then, the episode gets introduced and the intro is over.

I was in awe. The extent to which the narrator developed this fiction, only set the scene. The storytelling, masterfully interwoven with audio segments, making for a seamless* podcast experience.

In Special Issue 23, I have become increasingly interested in the power of fictionalization. Examples seen in this SI include:

- Documenting through Dialogue https://www.metamute.org/sites/www.metamute.org/files/pml/irational-orgs-traum.pdf/

- Map is the territory, a digital zine intended as an introduction to the command line in wizardly fashion.

- The chopchop oracle: presenting a welcome message randomly selected from a pool of diverse samples.

This podcast episode reinforced this already growing interest and fascination. I guess you start to notice more examples, when you start to look for them. Having a character share their name with a book's author, for example, a decently 'common' technique in literature (and in my experience especially in Dutch literature (e.g. Blauwe Maandagen, Grand Hotel Europa, Hedonia, ..., but also Everything Is Illuminated)). Film can do this too (e.g. Curb your Enthusiasm). For a seemingly small thing, this carries a tremendous power in engaging the consumer. What is real and what is fiction? Embracing this ambiguity primes the consumer for a real engaged connection.

103: Fugazi, Merchandise

- Listened to on 2024-02-17

- Listen to it here

It's August 2023 and I'm in Samara, Costa Rica, on the phone with my good friend Mats who has been researching cyberpunk as an aesthetic, a medium and a vision. He asks: 'beschouw jij jezelf punk?'

XPUB has some very obvious connections to punk (the DIY mindset and the critical stance towards big corp), and I have found an exploration of punk movements to be very insightful for the course. This podcast episode is about Fugazi. Many anecdotes serve as a reality check, for example their policy of self-distribution, $5 concert tickets and no merchandise (see even the bootleg library), which are policies easily translatable to publishing and design practises (e.g. self-publishing, pay-what-you-can rates, and the tension of creating cutesy stickers to make up for any missed revenue streams). But at the same time, it reminds me of the continued relevance of why these policies are in place. And while a self-published product can sometimes feel small, it is exciting and empowering that I -- a person of a different generation, a different country, a different context all araound -- can find meaning in products that found their existance in a similar way, with similar intent, 40 years later.

In the current special issue, we have taken an unexpected turn into game development. In this project, I am reminded again why this is so interesting to me. After listening to this episode and returning to class, I am for the first time trying to apply view the (indie) game industry through the lenses of these mentalities. I absolutely dare not fantasize about graduation projects yet (but there is some potential there...).

References

- ↑ Malevé, N. (2020) 'On the data set’s ruins,' AI & Society, 36(4), pp. 1117–1131. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-020-01093-w.

- ↑ Star, S.L. (2016) 'Misplaced concretism and concrete situations: feminism, method, and information technology,' in The MIT Press eBooks, pp. 143–168. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/10113.003.0009.

- ↑ Hilbert, D. (1903) Grundlagen der Geometrie.

- ↑ Luscure, J. (2003) 'Six Selections by the Oulipo: A Brief History of the Oulipo,' in The New Media Reader. MIT Press, pp. 172–176.

- ↑ Calvano, I. (1986) 'Cybernetics and Ghosts,' in Oulipo: A Primer of Potential Literature. Lincoln : University of Nebraska Press, pp. 3–27.

- ↑ Luscure, J. (2003) 'Six Selections by the Oulipo: A Brief History of the Oulipo,' in The New Media Reader. MIT Press, pp. 172–176.

- ↑ Charles Rowe, B. (no date) bevrowe.info. http://www.bevrowe.info/Internet/Queneau/Queneau.html (Accessed: June 20, 2024).

- ↑ Scott Kraft (October 10, 1981). "He Chose His Own Adventure". The Day. Retrieved June 20, 2024.

- ↑ Sandi Scaffetti (March 30, 1986). "Interactive fiction". The Beaver County Times. Retrieved June 20, 2024.

- ↑ Calvano, I. (1986) 'Cybernetics and Ghosts,' in Oulipo: A Primer of Potential Literature. Lincoln : University of Nebraska Press, pp. 3–27.