User:Thijshijsijsjss/Gossamery/The New Media Reader/The Oulipo

- Read it here

- Recommended by Steve Rushton

The New Media Reader, Edited by Noah Wardrip-Fruin and Nick Montfort, 'collects the texts, videos, and computer programs that chronicle the history and form the foundation of the still-emerging field of new media'. It presents a timeline starting at the 40s with the likes of Borges and Turing, spanning to the 90s.

Chapter 12 is dedicated to the Oulipo, with a selection of six works and a general introduction contextualizing the group. This introduction attempts to shed some light on some of their core ideas, for example:

[T]he Oulipians realized that such a system had the potential to define a new type of computer-mediated textuality, producing custom poems in ways that give the reader an enhanced role in the process of literary creation.

One might wonder how this expands to other fields -- especially now that the technological capabilities much more easily facilitate for interaction -- like film and gaming. In the latter case, there are many examples of games that are 'merely a framework for the players' creation': Garry's Mod, Ultimate Chicken Horse, Super Mario Maker, even Minecraft.

In film, there are choose your own adventure projects, but in my experience so far, they are often stiff and don't realize the full potential of their form. Again, if we return to games, we do see interactive video projects, like Her Story.

Either way, I see this 'enhanced role' as hopeful. In the current landscape of media, one is flooded by content in ways that reduce agency, to a point that one wants agency no longer, just consumption. Maybe this enhancement can be a challenge, a provocation to combat the symptoms of a generation.

[A computer that takes a very large space of possible stories and narrows it down to one] is a potentially powerful story-production method, and yet the conclusion of Clavino's essay argues that the solution of any algorithm, the narrowing of even the most artfully constructed set of combinatory possibilities, cannot create literature. He states that it is the 'clinamen' which alone can make of the text a true work of art. The climanem is the deviation, the error in the system.

This is echoed in Calvino's lecture Cybernetics and Ghosts -- the text read before this one in the chronology of the relation between these specific texts and this specific figure of a reader. This idea resonates with me. Not only in arts, but in life in general I have found many activities to be awkward, frsutrating and painful experiences that I stick to, because I know that sticking to it means eventually finding the 'click', that one connection, or one climanem or however you want to describe it, that lets me find a new meaning within myself. In many ways, this reader (referring not to my person, but to this collection of annotations and thoughts) is such an experience.

The potential that lies within such an understanding of interactive experiences is a recongifuration of the relationship between reader, author, and text. The playful construction within constraints that the Oulipo defines as the role of the author can become an activity extended to readers, who can take part in the interpretation, configuration, and construction of texts.

Reader is a curious word for an 'object' like this. It describes an agent, whether that is the agent 'to be read works', or the agent 'reader' created when interacting with this object. It occurs to me that it is no coincidence, perhaps, that this particular reader is not a noun, but rather an adjective: a suggestion of what this interaction for 'the object reader' might be like for 'the person reader'. A word capturing their connection, maybe.

A Hundred Thousand Billion Poems

According to Jean Lescure [1], Raymond Queneau's A Hundred Thousand Billion Poems (Cent Mille Milliards de poèmes) is 'perhaps the prototypical example of the Oulipian potential'. It presents 10 sonnets -- all not only following the same rhyme scheme, but the same rhyme sounds, too. Allowing the reader to swap any line with another from the same position in another poem, the reader is invited to become part of the process of literary creation.

Online versions (like one by Beverly Charles Rowe [2]) beg the question what role materiality plays in this process. I myself notice my exploration of the potential to be subtly different rearranging paper versus selecting by mouse click.

Yours for the Telling

- Read on 2024-06-19

- By Raymond Queneau, translated by John Crombie

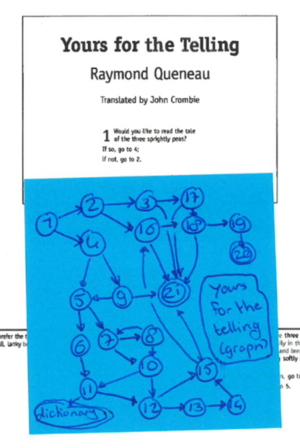

A cute, short choose-your-own-adventure-like story that with 21 'nodes' manages to realize many mechanics of the genre: branches, different endings, loops, and directions that let you escape the graph of story nodes all together (in this case by referring you to a dictionary to acquire your own interpretation).

This work was originally published in 1973, preceding the CYOA books made by Edward Packard that started serial publishing in 1976 and book publishing in 1979 [3][4]. Just like these stories, Yours for the Telling doesn't shy away from making the choices explicit, though not diegetic -- contrary to the way this is often done in contemporary video games. However, there is a difference between Queneau's story and those of Packard: in Yours for the Telling, the 'you' addressed in the story is the individual of the reader. There is no seperation between the 'you' reading the story and the 'you' addressed in the story. This in stark contrast to the CYAO books: the addressed 'you' deciding to venture into a dark cave is a 'puppet-you', controlled and existing in the mind of the 'reader-you', but whose existences doesn't fully coincide. (Compare this to Calvino's Cybernetics and Ghosts, section II[5])

Just like with A Hundred Thousand Billion Poems, there's the question how the form factor impacts the experience. I have noticed that digital choose your own adventures (literal ones, or more videogame-y ones where the options are implicit or the option space invisible) often don't convey this feeling of sprawling potential to me. In a paradoxical manner, being able to capture the bounds of the story, its graphical finality, makes me feel the optionality and interconnectivity more.

A Brief History of the Oulipo

- Read on 2024-06-20

- By Jean Lescure

This text presents an overview of some Oulipo history and by doing so, naturally has connections to many other texts. For example, some touched upon ideas about inspiration and the definition of literature are explored in more depth in Cybernetics and Ghosts, by Oulipo's Calvino.

More interesting, maybe, is a connection present through all work by the Oulipo I have met thus far: a connection to the concept op play. In this text, Raymond Queneau's Odile is quoted:

The really inspired person is never inspired, but always inspired.

With this statement, the objectivity of literature is implied (according to Lescure). This objectivity made it possible to explore literature through the modes of manipulation, as one would explore the field of mathematics. This exploration is often game-like. In fact, it's even referred to as 'games of language' or 'combinatorial play'. In Homo Ludens, Huizinga declares the first characteristic of play all play is a volunatry activity. We see this sentiment reflected in the play of language, by Queneau's words:

The only literature is voluntary literature.

For a Potential Analysis of Combinatory Literature

Computer and Writer: The Centre Pompidou Experiment

- Read on 2024-07-08

- By Paul Fournel

A short text describing early applications of computers (CLIs) in literature. Fournel creates two categories, the first one being so naturalized now that it is almost surprising to see it written: aided reading. In this case, it isn't so much about providing accessibility through technology, but rather that the physical action to consume certain texts can be awkward, tedious or take away from it's contents. A Hundred Thousand Billion Poems is given as an example: the strips of text are too tedious to manipulate. Instead, a computer could present you the different poems tidily. Another example given is Yours for the Telling, with the motivation that the game dominates the reading of the text itself. I can see how these examples have some truth to them, but as stated in other entries, to me the form is so much of the message that it's difficult to translate the experiences in more streamlined ones without losing their defining merit.

The second category is aided creation and concerns the involvement of the computer between author and created work. Multiple flavors are described, one of which being: author > computer > reader > computer . work. The author provides some 'building blocks' for the reader, and they 'build' something that then becomes the work (with computational involvement along the way). This sounds not only very xpubian, but also has untapped potential in many fields other than literature (e.g. Print-and-Play Games). In Cybernetics and ghosts, Calvino describes how the 'I' is split when writing. This flavor of aided creation also suggests a split of the work itself: an imagined work as conjured by the author, an intermediate work as shown to the reader, a 'completed' work as handed off by the computer, and many a potential work for different combinatorial outcomes.

Although aided reading and creation have evolved and naturalized a lot over the almost 40 years since the publication of this text in 1986, I don't know if these various applications have so much concerned themselves with literature. Or rather, if contemporary literature wants to concern itself with them. In fact, with recent AI developments, aided creation is getting a negative connotation. But what about all those aids we like to ignore? Is a thesaurus not a combinatorial writing aid? Is my writing not fundamentally guided by the interfaces in which I write?

Prose and Anticombinatorics

- Read on 2024-08-01

This text by Italo Calvino is a direct follow up to Paul Fournel's The Centre Pompidou Experiment, both in The New Media Reader as in their original publications. The former explicitly references the latter in the introductory words. In contrast to Fournel's text, that investigates the use of a computer as a literary aid in realizing combinatorial potential, Calvino's focusses on the anticombinatorial character of the computer aid that from a large number of possibilities selects those few realizations compliant with specific constraints.

The text starts with an exerpt from yet another text by Calvino, a short story in the making, in which a book is report is found that describes twelve sinister events. The task of the story's protagonist is to find the people who were guilty of and were victim to these acts. Calvino then goes on the descirbe different categorizations of the acts, and gives sets of constraints that might acts as deduction rules. As an example: an act of suicide by character A might not preceed an act of blackmailing by A, as A is assumed to by dead by the time of the second act.

With these sets of constraints, a computer aid can produce scenario's possible. This, Calvino argues, is not an act of replacing the creative act of the author. Instead, it liberates them from the chains of combinatorial search, allowing them to focus on the 'clinamen' that with which they can lift the text to a work of art.

References

- ↑ Luscure, J. (2003) 'Six Selections by the Oulipo: A Brief History of the Oulipo,' in The New Media Reader. MIT Press, pp. 172–176.

- ↑ Charles Rowe, B. (no date) bevrowe.info. http://www.bevrowe.info/Internet/Queneau/Queneau.html (Accessed: June 20, 2024).

- ↑ Scott Kraft (October 10, 1981). "He Chose His Own Adventure". The Day. Retrieved June 20, 2024.

- ↑ Sandi Scaffetti (March 30, 1986). "Interactive fiction". The Beaver County Times. Retrieved June 20, 2024.

- ↑ Calvano, I. (1986) 'Cybernetics and Ghosts,' in Oulipo: A Primer of Potential Literature. Lincoln : University of Nebraska Press, pp. 3–27.