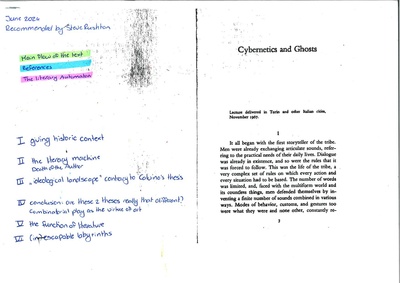

I.

The running thread throughout is one of tribal storytellers. They play a combinatory game with figures (jaguar, toucan, man) and actions (sleep, die, climb). By exploring the permutations, stories emerged. These always contained correspondences or contraries, and they allowed certain relationships among elements, but not others (e.g. prohibition must come before punishment). Propp notes that such tales are all variations of a single tale. Lévi-Strauss notes the mathematical process we can thus apply to anthropological questions.

Is this only true of oral narrative traditions, or of literature as a whole? Quickly, the combinatorial play of narrative possibilities goes beyond the level of syntax, grammar and content, to touch upon the relationship of the narrator to the material and to the reader. Writing, Calvino notes, no longer consists in narrating, but in saying one is narrating. 'The psychological person is replaced by a linguistic or even a grammatical person, defined solely by [their] place in the discourse.'

He goes on to describe the current world's 'triumph of discontinuity' -- things that once appeared continuous, are now looked upon as discrete. Thought, for example, has gone from a fluid matter to a series of discontinuous states. 'Not even in a lifetime lasting as long as the universe could one manage to make all possible plays.' We are starting to realize the infinitesimal size of these actors. Every analytical process -- every division into parts -- reveals a world even more complicated. In chemistry, history, and liguistics too: the American School led by Chomsky (deep structure of language), the French school of Greimas (structural semantics), the Soviet school headed by Kholmogorov (neo-formatlist), the French Oulipo founded by Queneau.

Having said this, the question arrises: will we have a machine capable of replacing the poet and the author? A literary automaton not only capable of 'assembly-line literary production', but of a deep exploration of psychological life. This question is not so interesting for the practical feasibility of it, but rather for the theoretical possibility and the conjectures it inspires. The true literary machine will feel the need to produce disorder, in reaction to its preceding production of order. It will eventually feel unsatisfied with its own traditionalism. It will, at last, be 'the' literature.

II.

With all written text, various theories on aesthetics maintained it was a matter of inspiration, something intuitive. But even these questions cannot answer the question: how does one arrive at the written page? Calvino states: literature as I knew it was a constant series of attempts to make one word stay put after another by following certain definite rules. Or rules that were neither definite nor definable, derived from the tradition of other writers. And in these operations, the person 'I' splits into a number of different figures: 'I' who is writing. 'I' who is written. An empirical 'I' who looks over the shoulder of the writing 'I' into a mythical 'I' who serves as a model for the 'I' who is written. 'The 'I' of the authos is dissolved in the writing, the so-called personality of the writer exists within the very act of writing.'

Thus, an appropriately instructed writing machine would be able to not just produce text, but produce an unmistakable 'personality' or figure of the author. What has been called talent or intuition is nothing more than empirical navigation. Something the literary automaton would be particularly rapid and multithreaded at.

Still, literature would continue to be 'a place of priviledge withing the human consciousness'. The work will continue to be born, judged destroyed or constantly renewed on contact with the eye of the reader. What will vanish, is the figure of the author. This gives rise to a more thoughtful prson: one who will know that the author is a machine, and will know how this machine works.

III.

Calvino then examines a contrary thesis. Did we say literature is entirely involved with the permutation of a limited number of elements and functions in language? But is literature not the continual striving to escape this finite number? To escape from the confines of language?

We return to the storyteller, who puts together phrases until something never been said is captured. Myth, then, is the hidden part of every story. The part that is still unexplored, because our words are lacking to enable us to get there. Thus, we need signs and happenings to venture there: rites. Myth is a language vacuum, nourished by silence as well as by words. He then connects this to conscious: isn't the subconscious similar to the myth? Just the region that has not yet been put into words in the conscious? The power of literature lies in in the willingness to give a voice to what has remained unexpressed in the social or individual unconscious.

IV.

We now make the jump to art in general, by examining puns. The pleasure of puns, says Gombrich, is obtained by following the possibilities of permutations and transformations implicit in language. The juxtaposition of concepts that we have stumbled across by change unexpectedly unleashes a precious idea. The processess of poetry and art are analogous to those of a play on words.

Hence, the literary machine can perform all permutations possible, but the poetic result will be the particular effect of one of these permutations on a [person] endowed with a consciousness and an unconsiousness. (An 'empirical and historical [person]')

Moreover, this conclusion is reached from the thesis of literature as a means to escape the confines of language. A thesis opposing Calvino's initial stance. Hence, we see that the two routes come together in the end: literature is a combinatorial game that purues the possibilities implicit in its own material, independent of the personality of the [creator], that is invested with an unexposed meaning not patent on the linguistic plane. Meaning that slipped from another level, activating something that on that other level is of great concern to the [creator] or society.

V. and VI.

In this concluding section, Calvino applies the concepts of combinatorics found within literature to the concept of literature itself. Literature itself is an acting agent, a figure subject to actions. For long periods, literature appears to work in favor of consecration, the confirmation of values, the acceptance of authority. But at a certain moment, something in the mechanism is triggered, and literature gives birth to a movement in the opposite direction (Le due tensiono, Vittorini). So far, literature has been too much of an accomplice of nature. Instead, the true value emerges only when it becomes a critic of the world and our way of looking at the world. Through literature, mankind achieved the critical spirit, and transmitted it to collective thought and culture.

Enzensberger writes about 'labyrinthe narratives'. He sketches the image of a world difficult to navigate. Every orientation presupposes a disorientation. Only someone who has experienced bewilderment can free themselves from it. Hence, games of orientation are in fact games of disorientation. The labyrinth is a challenge: if you escape, its power is dissolved, because for whom have traversed the labyrinth, no labyrinth exists. The moment a structure appears as metaphysical, the game loses ists dialectical balance. If literature is metaphysical, it is essentially impenetrable, unescapable, and communication is impossible.

It is up to the reader to see to it that literature exerts its critical force, and this can occur independently of the author's intentions.