Rossella: Text on Method

We must reveal an individual reflected in the glass who persists in his illusory country (where there are figures and colors, but they are ruled by immutable silence) and who feels the shame of being only a simulacrum obliterated by the night, existing only in glimpses. —Jorge Luis Borges, After Images.

The work Universal Time has been planned as divided into several chapters, with each chapter functioning as a separate independent module, although all modules are thematically connected in various degrees to the rest. In its finished form it will be a multimedia work, combining visuals keeping at the border between still and moving image, and then sound and text, and possibly web presentation. Space, in its widest sense, will be essential to bridge the various elements together, also by providing a unifying framework to it.

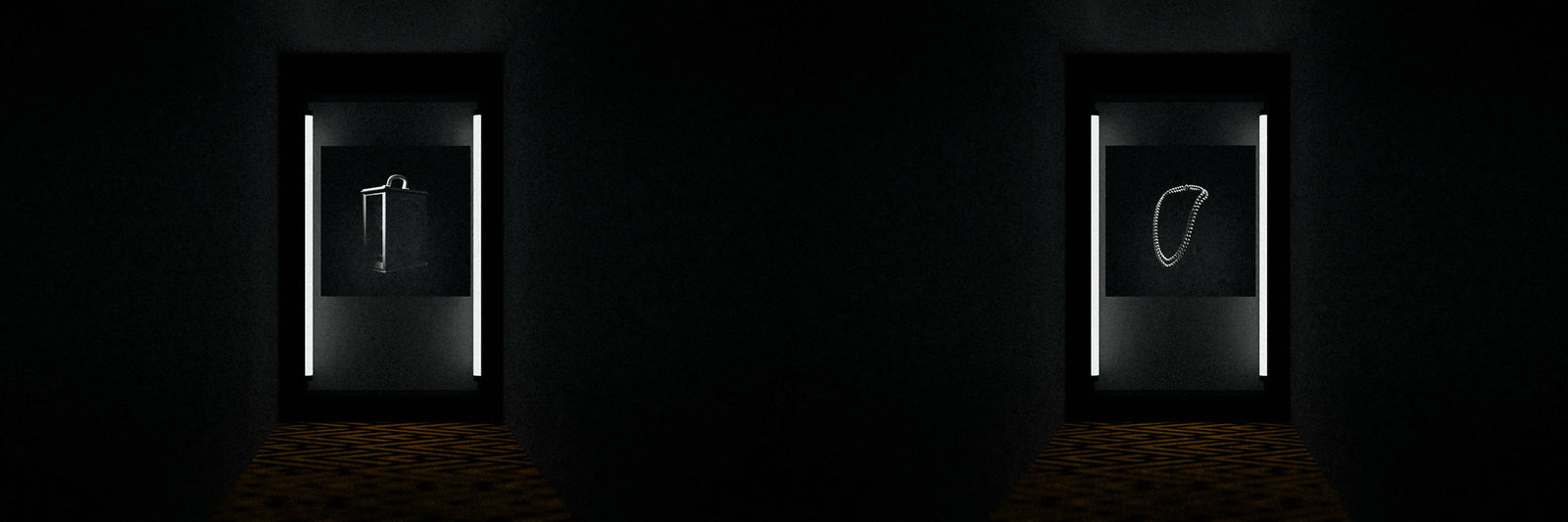

The first chapter, currently underway, comprises images of iconic objects found in historical visual documentation, specifically in official and semi-official portraiture of political figures from the 20th century and onwards. While the focus is certainly on the ambiguity of meaning and purpose of the objects chosen by political leaders as representative of their authority, it is also about the historical conditions surrounding them, and about the creation of the mystique of power. The images are monochrome virtual replicas of the object, stripped of their contextual references as if existing in an atemporal dimension. Deprived of any specific material quality and chalk-like, all the replicas emerge like phantoms from the same pitch black background, while minimal lighting is in place to emphasize character through the object’s simplest physical components, its lines and mass. Thus, I turned the objects into metaphorical embodiments of power structures, a gateway to what lies behind them. At first having visualized this first chapter of Universal Time as collection of stills, a catalogue of sorts so to speak, I broadened it into the plan for installation, with expansion into publication work.

In part, I unconsciously dreamed up this module as a process of re-elaboration in contemporary terms of the Musée Imaginaire of André Malraux, which establishes a discourse between ages and styles in art through super-impositions of artifacts that are geographically and historically diverse within what Malraux describes as an imaginary museum, one which wouldn’t need to comply with the material and conceptual restrictions of actual musea. I therefore ventured to borrow from the imagined museum that Malraux envisaged the notion of conflagration, of assemblage of curiosities, one however that, I believe, has a certain inherent gravity to it.

"Each exhibit is a representation of something, differing from the thing itself, this specific difference being its raison d’être." —André Malraux, The Museum without Walls.

In a similar vein to Walter Benjamin, Malraux considered photography the medium that would allow for such freedom of juxtaposition by means of its capability of reproducing the real, with the reproduction resembling its original and at the same time standing as something entirely different from it. I see the use of the virtual replica, which is a theme that I incorporated in earlier works (The Hiraeth Records, for which I built the prototype for an infinite house from personal memory being an example of it, and more recently Repérages, which set up an alternate version of migrant shelters and squats in Italy being another), as an evolution of the same concept. The interest I feel towards the replica however goes beyond these considerations and is connected with fascination for fakery and make-believe. The objects of Universal Time acknowledge from the start their being nothing more than look-alikes, that is to say exemplary impostors or, by a stretch of imagination, ghosts of ghosts.

I’ve been at work on the project on and off during the course of the last six months—it’s actually a little longer than that, to be more precise. The current module is still unfinished, and will be for some time yet, but there have been several developments in its conception from the initial phase. The visual catalogue plan, which is still discernible within the current project but is not encompassing it fully as it was originally intended, was informed both from a stylistic and from a conceptual perspective by previous work I developed, which was heavily centered on the still image. Preliminary arrangements for a second chapter started in parallel to it.

Earlier work I made was mostly photographic, at least in its intentions. Much of the photography that I produced was influenced by street photographers like Lee Friedlander and Saul Leiter, even though in combination with esthetics deriving directly from film. I moved away from the documentary approach and started to incorporate in my photographs heavily staged elements, mostly still lives in combination with digital collage. In several instances text, which was often a reworking of existing content—myths and folklore, public and private chronicles, news items both of trustworthy and dubious origins, excerpts derived from other texts of various nature, and so on—played a role as a counterpoint to the images, running alongside but never actually meeting with them. It is by producing work of this kind that however I realized that the still image, even though it provides a helpful canovaccio on which to direct my efforts, has some inherent limitations that even with the help of text I couldn’t always overcome. Indeed, the significance of the accomplished still resides in its silence, in its immutability, in its capability to captivate within the boundaries of its constraints; at the same time its self-limiting, self-contained nature doesn’t always offer adequate support nor breathing room for conveying impressions going beyond the superficial level or for evoking sufficient responses.

Coming from the study the theory of film and theater and having worked with editorial writing for several years before taking up photography, I find it a necessary requirement for any work I produce to have a verbal subtext. Which is the reason why my starting point is always a text—or a sentence, or even just a word—and only rarely it is an image. Words can refer to story, even though what I consider story doesn’t have to be intended as such literally: most of the time it’s not an actual, full-fledged account, but it is rather a hint of it, a fragment, something akin to the marks on the papyri salvaged from the sands, which only contain a few words of a much larger epos, the rest being lost.

In the first module of Universal Time text will not have an manifest prominent function, but will come into play as an appendix, to provide depth to the visuals, possibly through a series of small publications which will not only retain in part aspects of the catalogue structure which was the starting point of the work, but will be most of all a way to restore a connection between the replicas and their original context, by incorporating research information into them in the form of minimal essays. The essays will be portraits sketched in words of the characters connected with the replicas. The references I am using are not only texts that are integral to the research—critical history books for instance, or a range of visual documents—but also works by other writers who have been making of the short essay a privileged form of communication to relate information in a vivid, imaginative format. Excellent examples of the genre include Berger, Borges, Eco.

Having acknowledged the importance of the verbal, I should also mention the role space has in my work at large and in the current project specifically. Film and theater naturally have each their own peculiar methods of dealing with the problem of space to create an illusion, but it’s when photography provided me with a direct approach to relating with space that I started to grasp its significance. The photographic medium, by forcing me to exercise constant observation, created the needed foundations for understanding the notion of space, of its complex physical and psychological implications, which is something that exceeds the verbal and ultimately transcends it. No space is totally neutral or void, and even what is considered as such is usually charged by intricate ramifications of meanings and relations. The alternation of empty and crowded spaces for instance, or the very idea of spatial arrangement, are capable of generating lasting and meaningful impressions, offering almost countless prospects for manipulation and exploration. Art is always to an extent about illusion, but the possibilities in the construction of the illusion are a sub-theme that I barely—or at any rate, only half-consciously—touched before, and I am currently willing to discover more thoroughly, even if for now it is mostly on a purely speculative level.

When I decided to expand the catalogue of objects idea, I chose to bring space to the foreground of the work. One of the ways I identified for accomplishing this effectively is through presentation arrangements. This is where the second chapter of Universal Time, which is conceived as a companion piece to the first, becomes necessary. Even though I stated that all the modules of Universal Time will be interconnected in some way, the first two chapters are complementary to one another and have been especially conceived as such. Chapter two will feature projections of swarming birds in flight, and I am currently exploring options concerning the use of either real footage of starlings murmurations or computer generated reconstructions of the same phenomenon. I believe the real footage, with its defined organic quality, would offer a more pertinent context and a poetic dimension to the uncanny artificiality the replicas. At the same time, using computer generated imagery would allow for a degree of control on the material, not to mention possible expansion into the realm of interactivity, that would not be achievable through footage of real birds. In both cases, the bird projection is intended to be paired with a variable selection of six among the replica images, which will be presented in a shared space that will allow them to establish a dialogue with one another. The birds representing sweeping movement of masses will be laid out in between observant rows of spectral objects, so that the static, restrained essence of the first module will be consolidated by the expansive scope of the other. The use of sound will be crucial in this system to help convey sense of scale and create an immersive environment.

Sound is an element that I had overlooked earlier, probably because I didn’t feel it related smoothly with the kind of still images I wanted to produce. However, having worked with video in the recent months, which put me in the condition of considering elements of the moving image construction other than the image itself and its accompanying text, I started to appreciate sound in full for the creative opportunities it can potentially offer. Because of its very nature, I see it now as a precious ally for the rendition of the idea of space that I am after. I am talking about ambient sound especially, but I don’t exclude interplay with spoken word. Like text and even more than text, sound can suggest without necessarily saying too much. It can disorient and mesmerize. One of the endeavors that I resolve to pursue is therefore to further my knowledge of sound concerning its production, its design, and its poetic qualities.

References

- The Hiraeth Records (2016)

- Repérages (2018)

- Universal Time I: Notes on the Commissar's Lamp

- Universal Time II: Notes on the Murmuration Projection

- Universal Time I-II: Portraits Booklet

Further Reading

- Augé, M. (1995), Non-Places: An Introduction to an Anthropology of Supermodernity, Verso.

- Benjamin, W. (2003), The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility (Third Version), in "Benjamin, Selected Writings, Vol. 4: 1938-1940", Harvard University Press, pp 251-283.

- Berger, J. (1981), Permanent Red: Essays on Seeing, Writers & Readers.

- Berger, J. (2015), Bento Sketchbook, Verso Books.

- Borges, J. L. (2000), Borges: Selected Non-Fictions, Deckle Edge.

- Eco, U. (2001), La Bustina di Minerva, Bompiani.

- Eco, U. (1992), Diario Minimo, Bompiani.

- Grasskamp W. (2016), The Book on the Floor: André Malraux and the Imaginary Museum, Getty Publications.

- Malraux, A. (1974), The Museum without Walls in 'The Voices of Silence', Granada Publishing.

- Markson, D. (2016), This is Not a Novel and Other Novels, Counterpoint.

- Walser R. (2015), Looking at Pictures, New Directions.