Universal time pt.1

intro

on the sacralization/desacralization of politics through petrified metaphors. the object in portraiture contributes to set up and cement the mythology surrounding the leader in a way not dissimilar from what established by religious iconography. it was the renaissance that made it a common practice in the arts to transfer to objects specific characters of the person portrayed.

when the political became separated from the religious and religion shifted more and more towards a private sphere, politics appropriated elements of its language. in authoritarian regimes the process of appropriation is glaringly evident, but democracies are not alien to it. in the case of official and semi-official portraiture of political figures, carefully selected objects are invested with the sacrality of power. there are instances however in which the objects acquire meanings not intended by either makers of the portrait or portrayed.

this chapter of the project attempts to give a reading of the mechanics of power by bringing forth the presence of such objects and stripping them of their original materiality and contextual references.

the commissar lamp

also known as people’s committe lamp, stalin lamp, narkomovskaya lamp.

production

1920s—1950s

first production dated late 1920s—early 1930s (probably as early as 1927, in celebration of the 10th anniversary of the october revolution).

differences in design and construction

the design and construction quality of the lamp was dependent on several factors:

- year of production: the first versions were not fully standardized and show a wider range of slight variations. they incorporated elements from pre-rivolutionary, non-native styles (art nouveau, especially). they were also better refined than later lamps as they were crafted in a more artisanal fashion.

- recipient: the lamp’s decoration, size and materials varied according to the rank of its owner. generally, only officials could own the commissar lamp, with higher ranking officers and state ministers owning lamps that were more imposing in size and made of higher grade components. it is known however that due to its popularity “civilian" versions of the lamp were produced as well.

- the lamp’s conventional ornament represents the famous hammer and sickle emblem cradled in a luxuriant wreath—of wheat, and/or leaves of oak, flax, laurel, and so on. in some specimens stars were also added. common alternate versions include the "admiral” variant for staff members of the soviet navy, decorated with nautical themed medallions. early and custom-made specimens don’t always display the hammer and sickle, but they already contain the wreath motif.

- the leg and base shape varied and depended greatly on the factory that assembled the lamp and on the date of construction. the power switch was usually hosted on the cord, but several specimens have the switch on the base of the lamp.

components

- materials included wood, stone, iron, copper, bronze, brass, nickel for the dome, the supporting structure and for the ornamentation;

- various kinds of fabric—most commonly satin, linen, or flax—were used for the lampshade.

it is possible that to an extent that earliest specimens had been built out of recycled parts from older pre-revolutionary lamps coming from warehouse and factory leftovers. this would explain the variety in material and design of the leg and base especially in the beginning of the production. wood and stone were used only sparsely. glass was generally not employed.

symbolism

the lamp embodies syncretism of various ideologies both as an object and in its structural/material features. beside the evident practical use, its popularity largely depended on its suitability to illustrate the ussr’s power and self-reliance.

- light: truth, righteousness, power of transfiguration, legitimacy. the ussr sees itself as the light of the world. soviet doctrine abundantly borrowed from religious symbolism.

- material: glass, commonly used in lamps in pre-soviet russia, was not employed in the commissar lamp and was replaced by other materials (see lamps in photos from before the 1920s, such as those in lenin’s and kalinin’s offices, etc.). scarcity and excessive price of glass was likely one of the reasons for the change. however, the lamp was adopted to exhibit the greatness of soviet manufacture and industrial advancement. by making use of materials such as metal and textiles, whose industries were seen as the pride of the soviet economy and pushed under stalin’s rule, the lamp became a symbol of the ussr as a competitive industrial power.

in official portraiture

the commissar lamp is a ubiquitous presence in official portraits of soviet leaders. stalin was depicted in several instances together with the lamp (various models). in the same fashion, other officials were frequently shown performing their duties at their desks in the company of the iconic lamp (see photos of kalinin in his study to see transition from pre-commissar lamp before the 1930s to commissar lamp afterwards).

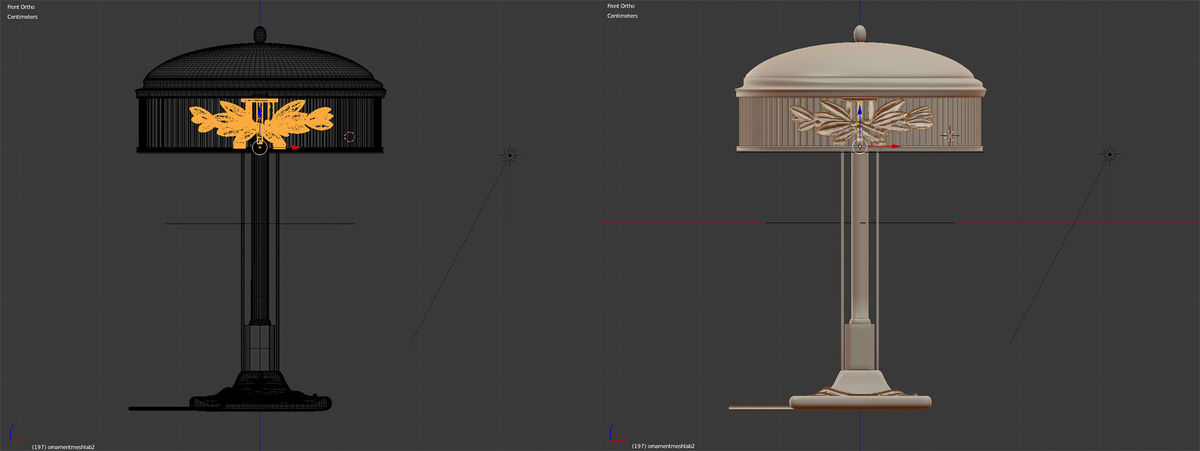

the replica

the replica of the commissar lamp that i decided to build and sculpted was based on the model that is featured in photographs of stalin in the kremlin from the 1930s. the canon of the lamp was not fully established and most certainly had not yet been trivialized by that time and therefore it doesn't feature the more commonplace hammer and sickle design. nevertheless, those photos were used repeatedly as the basis for posters and memorabilia from the stalin era, making that specific lamp design, in a way, iconic.