Universal time pt.2

During my first year as a university student, a time that feels now as remote as a mythical once upon a time, I had lots of time to kill between classes and was often sitting on the steps facing the historical buildings overlooking Piazza della Repubblica in Rome, a spacious circular square adjacent Termini on one side and via Nazionale on another. The university was hosted in one of those old buildings and the weather was so mild at all times that one could sit outdoors for a while even in winter. Overall it wasn't such a bad location to be killing time. It was precisely during the winter that, at the time of the day when the atmosphere turns into a muted vermilion shade before shifting to deep azure, huge murmurations of starlings used to fill the sky over Termini and were clearly visible from where I was sitting, waiting for classes to start. Before dusk, all of a sudden immense masses of starlings raised in the air and started moving together, one moment shrinking, the other expanding like a living vortex. The noise the winged cloud produced was deafening too, and even from my spot, several hundreds meters away, I could hear it distinctly. Several times I just sat there looking and wondering, until the sky gradually grew so dark that no bird shape was visible anymore.

Which reminded me how in the book Palomar the main character looks from his terrace at birds populating the skies of a city—which also happens to be Rome—and wonders at the spectacle of the contemporary urban space as seen from their eyes. He states,

“It is only after you have come to know the surface of things that you can venture to seek what is underneath. But the surface of things is inexhaustible."

Many times I imagined Palomar would be driven to his lucubrations by quietly observing murmurations as I was in those days in my early 20s. I say imagined, because in truth Palomar doesn’t mention starlings at all.

Nobody knows exactly why starlings flock together in large numbers ranging from few hundreds to millions of individuals at the same time. Unknown are also factors influencing size and duration of the event. The so-called starling murmuration (which owes its name to the sound produced by numerous wings beating at the same time) is a relatively little studied phenomenon. There are however many theories circulating in communities of ethologists, ecologists and biologists concerned with bird behavior that seem plausible enough to explain it, even though none of them is considered the final answer to the riddle. The most commonly accepted theory maintains that the flocking of starlings is a protective strategy through which the birds aim at confusing predators before going to roost. The wavy shapes produced in flight would therefore be a response to attack which sees the birds all moving together as a singular cohesive organism—something similar to what happens also with schools of fish. The event takes place after the breeding season (spring-summer) is over and the young, now fully independent, band together with their adults. Starlings are known to break in small groups during the day to feed, and only gather in large murmurations at the end of the day.

The image of a living mass in permanent motion came back to me recently, as I was strolling idly around Hillegersberg. It would seem I still have time to kill, sometimes. It was not the season for starling murmurations, but the area has a conspicuous bird population and a casual discourse about bird anatomy came up randomly in the course of a walk. At that moment I was looking for something I could use to complement the portraits-through-objects series I am working on and had been thinking about the issue with a sort of blind animosity for a while. During the conversation I saw in my mind’s eye the remote image of the starlings clouding the skies over Termini and intuitively I knew I had found the counterpart I needed. It was one of those moments where intuitive reasoning seems to make more sense than logical thinking.

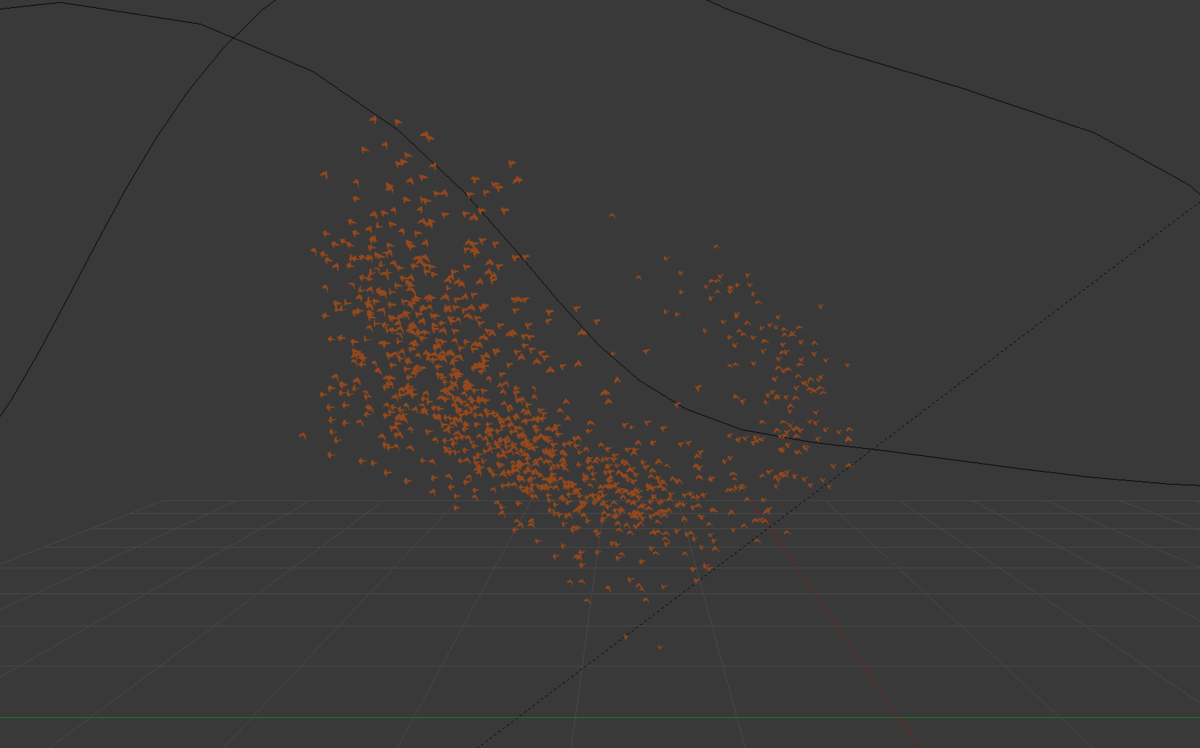

I see my objects as surrogate predators of some kind; their vagueness, stillness and silence don't make their original meaning less threatening. A projection of swaying masses of birds is supposed to move in between the objects as it would between natural predators. In the moving image of the birds I would like to preserve a degree of the sense of sublime that the spectacle of birds as I experienced all those years ago evoked in me, an undefinable synthesis of wonder and horror. The effect is hard to convey in a recorded form, and even more so with a completely digital reconstruction. I’m finding the challenge both stimulating and frustrating, as I discovered that even within the boundaries of a reconstruction I cannot have total control over my flock. Which perhaps is, in its own way, a smaller riddle within the other.

Sources

- Calvino, I. (1987) Palomar, Einaudi.

- Goodenough, A.E., Little, N., Carpenter, W.S., Hart, A.G. (2017), 'Birds of a feather flock together: Insights into starling murmuration behaviour revealed using citizen science', PLOS ONE, vol 12, no. 6, pp. 1-18.

- Procaccini, A., Orlandi, A., Cavagna, A., Giardina, I., Zoratto, F., Santucci, D., Chiarotti, F., Hemelrijk, C.K., Alleva, E., Parisi, G., Carere, C. (2011), 'Propagating waves in starling, Sturnus vulgaris, flocks under predation' Animal Behavior, vol 82, no. 4, pp. 759-765.

- The Cornell Lab of Ornithology

- Starling Survey