Jujube/methods-session-11

Calendars:Networked_Media_Calendar/Networked_Media_Calendar/10-04-2019_-Event_1

The final version can be found at: Jujube/text-on-practice-2019

I have called myself an artist for the past two years. For a good part of it I talked about practice in its trendy, contemporary context: text-based practice, practice-based research, my practice in the intersection of geography, architecture and psychology, of ontology and epistemology, of space and time. I used words because I had them, not because I understood them.

I equated practice to the projects I made, or the ideas on which I based my projects. I armed myself with a certain language and was proud that I could create the optics around a narrative. I wrote no fewer than ten proposals in the year of 2017 for artist residencies, appropriating my practice each time to fit the parameters of an open call. I was accepted by a few, waitlisted at a rather prestigious one, and of course, rejected by the others. Throughout the ones I did participate, I was able to create things; some of those even led to the curiosity and seriousness towards image-making I now hold close to heart.

But most of the things I created were neatly bookended by a start and end date and scoped with a well-phrased, sure-sounding outcome. Site-specificity was a convenient concept: everything the site introduced -- be it the environment, the people, the theme -- became a way to frame a sort of research. I would go on field trips and read literature about the locality, then try to write about it and produce something in the forms I knew, namely, text, photography and websites. I felt I had to keep on going to residencies in order to keep making. If I didn't I would lose the momentum, inspiration, or, dare I use the word now, legitimacy as an artist.

Practice became cool and abstract, or cool because it was abstract, or abstract because it was cool. It did not matter much: and that was why it was dangerous.

I was four when my parents enrolled me in piano classes. My fingers were so small that they could not press the keys all the way down. I practiced Tchaikovsky, Chopin and Beethoven everyday for more than an hour throughout elementary school, even when I hated it, which was most of the time. I stopped when I boarded for middle school. It was the first kind of practice I had in life.

Practice makes perfect. It's trite, and whether or not I admit it, it's true.

A conversation via email before I came to Piet Zwart.

I applied to a few programs in NL and was accepted by two. Now I am trying to decide which program to spend my next two years or three. My rationale for the first one is that I can treat it more like a long-term residency while becoming better as an artist-curator (more versed in theories and seeing and using connections). For the latter, I applied because I enjoy working with the lens — I got a nice camera last year and have been feeling so much potential with it. And I always refer to our conversation on craft: the lenses can become part of my tools and I can be more versatile in ways of manifesting my work. How has your trajectory been — I guess, how does theory and research inform your work and how have “forms” and “media” do so?

For me, theory and research on its own becomes overly academic and stagnant. It feels like ideas that are talked about, but never graduate into anything impactful. Keep in mind, I come from a mindset that tries to use art as a communication method for a broad audience - so art that stays purely in the realm of academia and research frustrates me. Likewise, crafts and skills on their own don't carry enough intent. I love process-driven work, I think it's really informative and a great basis for practice, but the real magic for me happens when the two combine. Somehow, when you layer theory and research with the process of craft skills - this third invisible element happens - the space created between the two elements that gives extra underlying meaning, purpose and intent for the work. It's hard to articulate, but I suppose when I look at an idea or creating a work, if I had to come up with a formula it would be something like this. Tool kit of skills + Concept = An art work that clearly communicates an idea through the use of a refined skill set.

I was in a playwriting workshop when I lived in New York. I wrote a short play (or a different draft of it) every week. On every Tuesday at the acting studio in Greenwich Village, where the afternoon sun poured through the wall of windows for the last golden hurrah before it set into the Hudson River, where the eighteen-year-old acting student from Czech Republic sat next to the balding Brooklyn Jewish poet to the Swiss princess to Elizabeth my love -- for that good year and a half, I brought a script into the room, cast my characters among the other workshop participants, and heard it read.

I still call myself a playwright.

I have been making films for eight months now. The first thing I made was a documentary without knowing what documentary-making would take. I watched tutorials online about placement of the camera and checked out a field recorder to learn which buttons to push.

It ended up taking me a few months to make a 14-minute documentary filled with interviews and mal-focused shots of faces at the wrong shutter speed.

For the second film, I wrote a script and went to a residency. I created an initial storyboard before departing Rotterdam, in which I set the main scenes near a lake to adapt a true story I heard a long time ago. When I arrived at the residency site, I was struck by the arid land.

Because I had only a week, I had to re-evaluate my script as I filmmed. I developed a routine right away. Each morning I'd leave the residency building, walk down into the barranco -- a type of ravine formed by erosion both by rainfall and agro-pastoral modification common in this region -- and observe the weather, geology, flora and fauna with my video equipments: a DSLR camera, two lenses, a field recorder, a pair of headphones and a tripod. At the end of the day, I would do a quick edit in front of the fireplace and create a new storyboard of the scenes that needed to be done the next day. The barranco inspired new vocabularies in the script and became the central image of the video. As I iterated through the images, I got closer to the image repertoire I wanted to build.

The method was noted in one of the tutorials:

- Abstract narrative

- Find location

- Improvise with the situation

Fast forward to now — which means the first and second films, a photobook, a zine and a public speech later — I started shooting more documentaries. With each person in my recent documentaries, I try to create a situation in which the person will arrive at feeling(s): of warmth, clarity, resilience. On camera I try to capture the emotional journey that they go through -- sadness, nostalgia, loss -- as they write, draw, walk, perform, i.e. as they conduct a certain activity.

I have repeated a directing method for making these documentaries: I schedule an individual meeting with each of my subject, listen to what they want to share with me, and decide with them what is a situation in which they feel safe to be vulnerable. I met my subjects (with the exceptions of two, whom I already knew) through a performance I did at Garage Gallery in Rotterdam. My act was the reading of a wikipedia list of neighborhood names of Brooklyn, during which I teared up. With a softened voice and state of mind, I led the audience on a meditation about the space called home.

The meetings have been a crucial part of the process. I try to communicate efficiently (when, where, what expectations) while setting up the meetings. When I finally meet them in person, I remain as open, honest and attentive as possible and listen.

Some of the situations I have created so far are:

- take Lara to Maastunnel for the installation of Tunnel of Love during Valentine's week

- go stationary shopping with Mia and film her draw a picture for her dad in a cafe

- follow the plaster casting process of Amy at the ceramic station

- follow the journey of Renate from Rotterdam to the Hague, film her write a letter at James Turrell's Celestial Vault

I filmed the situation with Lara by myself, but found it extremely difficult to conduct the filming, recording and directing all at the same time. For the two shootings that followed I recruited Cem and Ugo, peers from the Master's program, respectively as the cinematographers. In this way I was able to focus on the sound and direction.

"You talk a lot about what you film and why you film it, but how do you film them?" Someone asked one day, and I could not respond. It felt I was asked to elaborate on the choice of obstreperous in the paragraph of the short story I would be writing when I had just learned the alphabets enough to spell o-b-v-i-o-u-s.

I changed my workflow again and became more deliberately involved in cinematography. For the shooting with Renate, Cem and I divided responsibilities. He shot the distant takes and the environment and I did the close-ups. Considering that it was one of the most vulnerable stories in these situations, we had an additional meeting with Renate before the shooting, and discussed our approaches together. What we tried to establish were boundaries, safety and trust.

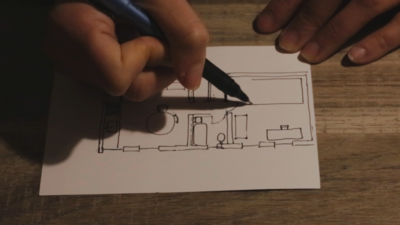

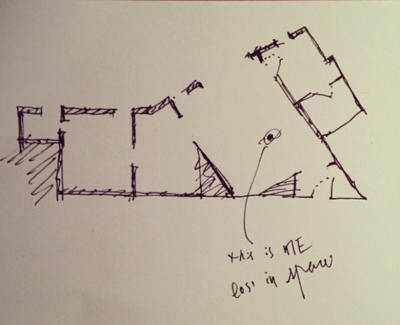

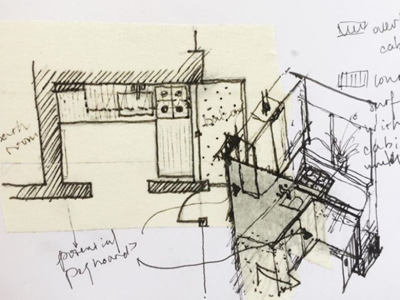

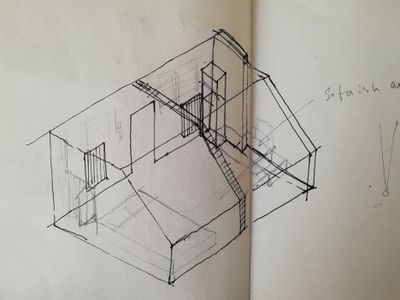

The place I sublet in Rotterdam when I first moved here was covered in dust trapped in grime. I spent a couple of days scrubbing the shower and wiping off the unknown particles coating the spice jars. One morning I drew an isometric plan of the kitchen. I drew it so that it would be better, so that every time I picked up the broken handle of a pot there would be something to hope for, even though when the end of my sublet came there was neither improvement nor fulfilment. When I moved from one house to another in Washington DC, staring at the empty room I drew a floor plan. By the window I shall have a desk no wider than 48 centimeters, and by the wall a shelf permitted by the ceiling height. I was quite obsessed with cushions and light bulbs. I wanted to fill the empty walls hard corners with not cold-tiled echoes but what softness that'd catch me. I wanted to know it, call it mine, and take care of it.

The first months in Rotterdam I kept walking through the apartment I dwelled in New York.

There is a walk-in closet on the right. A giant mirror in front of you, a false wall that divides the living room into entry way and open kitchen. Walking past the right side of the couch, you see the kitchen sink, the stove, oven, the cabinets above them. (The sink is white and deep, the faucet tall with a generous curve, almost the same as the one you once saw in a farmhouse on the border of Vermont and New Hampshire where the owner decided to follow the Swedish vernacular.) You open the fridge. There is a bottle of coconut water (pink when you bought it, which the label says is a natural coloration) and a couple of Siggi's yogurt. You open one cabinet and find plates, bowls, mugs with a shade of grey purple which some interior color reference book has claimed slate. There is a round table where you eat and write. A bookshelf whose top you filled with play scripts. A map of the Second Valley in Pennsylvania that you bought for the thin topographic lines and the humility it reminded you of.

I moved from an airbnb to the dusty sublet to a six-month temporary rental to my current place. The first week I moved in I measured the walls and drew the room.

I grew up under Buddhist influences. My mother is a Buddhist, and I remember being dragged to the temples to pay respect to the Buddha. I would enter the temple, light up the incense, enter one wing and say hi to the Bodhisattvas, then the Buddha, gold and big and with the droopy eyes that they call kindness. My mother still keeps a Buddha room in the house, where she goes everyday to make good wishes.

When I was in college I had the chance to design a building for one of the religions in the world as my architecture thesis. I chose Buddhism because I could finally question, openly, whether it was a blind superstition. After all, I prided myself with the aptitude from the Enlightenment.

Despite my skepticism, I arrived at this: if the repeated act means anything, it spreads existence -- and the anxiety, contemplation, peace thereby -- across the most mundane tasks. And if you have wished for the health and safety of your family, every morning, for the past 60 years in your life, you have known one thing or two about love.

I have been writing this imaginary correspondence with Su, a Korean artist I met at a residency and have not contacted since the residency ended. I started writing to her from the beginning of my time at Piet Zwart, in September 2018. After writing these letters for more than half a year, they have become documents of the more personal feelings that I have no one to share with in Rotterdam. I included two of these letters for a recent assessment as a way of showing the sometimes unconscious drive of my process. (Perhaps I will bring them to light one day.)

I made bread at a bakery for a period of time. I would get up at 6:45 in the morning and leave the house by 7:30. By 9 I would have mixed at least 20 kilos of dough for one kind of bread and in the middle of waiting for the autolyzing to finish for the second kind. By 10 I would have folded some dough in development. Folding the dough was like tucking a child to bed -- I'd lift up the sides of the dough as if it were a blanket, stretch them and place them neatly under their own weight. In four hours I would start shaping the bread, first by cutting them into 1100 or 940 gram pieces. If it was a long loaf used by restaurants, I'd flatten out the dough a bit length-wise and roll it back with the shorter edges, then cradle it with the pinky side of my palm and push the mass towards my body to create tension in the surface. If it was a regular or small loaf, I'd fold the corners into the center and cradle from there. Sometimes, when the dough was very wet (because the temperature was high or because someone put it a bit more water in the mix that day), I would have to fold in the corners twice.

Before I knew it it would be five thirty in the afternoon. I would have set five timers (three to four times for each one), oiled eighteen tins, run the dishwasher on intensive wash thirty-one times, pushed three carts of fourty plus proofing baskets to the cooler, swept the floor, wiped the counter and sink and finally, changed out of my bakery shoes.

I would be tired. My calves would be swollen. My shoulders would be stiff.

I would say as I left the door: see you tomorrow.

END OF ESSAY

outtakes

Between long- and short-term makings (aka. between practice and projects)

With long-term makings I am able to change parameters in my methods. The process offers space to experiment (not unlike in a scientific study, I can choose to change different parameters of the experiment).

More defined projects afford less room to try things out. In the case of the thematic workshops, the form of the production is pre-determined, and whatever I explore becomes keywords for the next thing to come. In the case of the MIARD film, the production cycle has proved to be time-consuming and stress-inducing. I struggled with the available visual footage and, after reviewing them and having a talk with Simon, decided to forego using any of the (research) footage she has collected. Instead I proposed working off of the women's accounts on their feelings during Beatriz's interviews with them. The interview that stood out to me was with a transgender woman. Because it was conducted over the phone, there was no visual image of this woman, but her voice and speech. She was articulate about her experiences with street harassment, first as a gay man, as a perceived, crossdressing man (during transition), as a cis female, and as a transgender woman. In the most recent edit I have woven together three women's stories (including the one from the transgender woman) and brought back some still shots of street footage as the background. I have a feeling that I am saving the story rather than telling it.

As I write this I am developing criteria for the kind of practice I want to sustain.

Reading and writing

My core research questions up to the point are:

- How do people feel, specifically, how do people feel empathic?

- How do images carry meanings?

During IFFR, the questions grew with concerns of autobiography and the image:

- How to translate autobiographical materials into empathic matters? Perhaps through myth and tales?

- What is image capable of in conveying that intention and — in the process or as a result — creating empathy?

- Also, not at a conceptual level but an aesthetic one: I'm drawn to the mountains, seas and remote places...Why? Out of the sublime, the metaphor, the unexpected forms?

As we formed the research group, the literature we have been reading has inspired some new, perhaps more specific, questions:

- What are the psychological processes of (collective) viewing?

- What is the difference between, say, cinema and gallery (physical space), or cinema and netflix (screen space)?

- How do focus, camera movement, editing affect the viewer's thoughts and feelings?

- How can we use cinema as a space for empathy? How do interacting layers of aesthetics and narrative change the viewer's distance with what is shown on the screen?

After reading Eric Schouse's essay, Feeling, Emotions, Affect, I realize that affects closely connect to core emotions. As a person fortunate to have experienced it in therapy, I believe the acknowledgement of and clarity about core emotions will enrich and enlighten one's self. My then therapist recommended three books to me. All of them seem relevant to my recent projects (not as foreshadowing frameworks, but as an emerging pattern as I make them). The books touch on neuroscience, development psychology, psychotherapy (A General Theory of Love); suffering, revisiting the past, healing (Reconciliation); and ways to access core emotions and arriving at clarity (It's Not Always Depression). In my next work I will try to externalize these connections and position my work in the framework of affect theories.

At the beginning of the program the word "autobiography" appeared frequently in my attempts. I noted the early, loose thoughts in the page named memoir. [1] For a couple of months, the driving force of my readings was personal memories, more specifically, how my own memory (and experience) can move others. I noticed my tendency of archiving without articulating the significance of that act, or only doing so in a half-baked way. A breakthrough came when I finished the essay investigating my relationship with autobiographic work. [2] I have since shifted more definitively from my own images (words, storylines, specific events) to those of an external origin.

Relying on my experience with narrative forms (playwriting, stage storytelling), I wanted to read about realms I knew little about. The Cinematic (Documents of Contemporary Art) has introduced me to photography and film theories. I like this volume because it makes an effort to distinguish between photography and cinema, not from a technological/historical point of view, but with more in-depth analysis of each medium. I have written synopsis of the essays from which I learned.

My interest in cinematography emerges with readings in The Cinematic and the creation of Seek. I have selected my readings directing towards the specificity of the techniques and studies of cinema. Through reading Mulvey, I will continue to expand my readings of haptic aesthetics (haptic visuality by Laura Marks) and the screen as a situation.

reading while making

I read The Cinematic, an anthology of film and photography theories, with the intention to familiarize myself with relevant film theory vocabularies. The benefit of reading the anthology is the quick access to a sizable amount of different perspectives in one single volume. The drawback, on the other hand, is the density of abstract ideas and abstraction. The anthology includes pieces of canonical texts as well as criticisms regarding these pieces. This anachronism was confusing.

Luckily, I was shooting for a video project while reading these and had a chance to contemplate the theories through doing. My script featured a voice in search of a lost past with imageries based in nature.

I came to realize that I am more interested in the cinematic — movement, association, directed experience in a set time — than the photographic — the captive moment that allows pondering for as long as one wishes.

So far, theories play a few roles in my practice:

1. Theories give me a historical perspective of what has been done. I am not studying art history in any comprehensive fashion, but through theories I am gradually learning to place my works and their relevance in accordance to the form(s) I choose.

2. Theories provide soundbites for rumination. I avoid jargons in describing my work (or even writing the imaginary wall text for it). When I read jargon-sounding words, however, the terms become starting points for connecting systems of knowledge. In articulating these connections I can strive to be genuine, specific, and unpretentious.

3. The case studies from theories give me works to see/watch/research, which helps widen my perspective. The fact that some of them resonate with me more than others drive me to inquire about my own preference — visually, narratively, affectively. By reflecting on other people's work I can also be more certain about my own aesthetics and processes.

Laura Mulvey introduces me to the early feminist film theories, which is the first kind of film theory I have read. It presents me with discourses that encompass my own fields of interest and situates me more in the vast space that (film) theories occupy. Perhaps now I can see more relevance of other key texts. (She makes references to Bellour and Metz, for instance.) As I read, I am noticing more and more the way(s) people describe image and image-making.

She shows me the tenacity of feminism (how it adapts to the times, how it reflects upon itself) -- it is an illustration of that so-called frameworks for research are, and should be, malleable, depending where I am in my practice. I am not interested in using feminism in my daily language. As Susanna said, "the new feminism is humanism."

The vocabularies of gaze and spectator feel very much the product of the last era (1970's). I am not interested in framing things with vocabularies "coined" to describe a certain thought or phenomenon. I am more interested in the everyday language, especially spoken with ingenuity. There is an intelligence that comes with the everyday language, one that connects people through shared words and the feelings they evoke.

I will keep reading academic writing as long as it helps me build connections among different knowledge systems OR gives me new insight about something, however esoteric, relevant. I will not set the tone of my research in an academic language. I am conscientious about the roles of theories in my practice and do not take any theoretical text for granted without the historical and cultural context in mind.

reading films

During IFFR I chose to see films that appeared to align with a few lines of inquiries. My criteria were:

- a story based on/inspired by myth/tales/rituals

- a highly personal story

- scenes in the mountains and/or by the sea

- alluding to the meaning of images"'

I see different ways in which the image carries weight. In some cases, the image is the most charged moment of the narrative, such as the scene when the word messenger faces gun point in Pájaros de Verano. In others, the image visualises a metaphor, like the woman catching water from all directions with buckets in Pattaki. Sometimes, the image becomes part of a well-written essay, as in Above Us Only Sky.

I find sound as important, if not more, as what I see. Sounds represent a place. In Tutto l'oro Che C'è, the wild track is the main track. Sounds create silence. Examples are the forest in Tutto l'oro Che C'è and water in Pattaki. Music can often be a narrative by itself, as seen in The Last Seven Words.

Actor-directed films can lead to incredibly tender moments. In Vulnerable Histories (A Road Movie), two characters both with painful family (and/or present histories) share their own feelings towards discrimination and inequality. In this case the director's role is to create a framework to communicate that clearly and foster an environment/crew that lets things be and happen.

ref

See Bibliography and IFFR log

steve's feedback on draft 1

[Steve's brief feedback on 1st draft. This is a very good start. I am struck in the first part of the text by the way in which you wish to create intimate situations and somehow represent them. The importance of belonging and calling a place home seems to be very important to you. I am intrigued by your letters to Su. In the various practices you describe in the first part, you serve as a host and you make an invitation; or you serve as a guest and accept an invitation. The commonality is the invitation to share a space and time. I think (instinctively) it is important that you develop a routine and allow the works come from that routine. A series of small works in which you are host or guest would be generative. You outline something similar in your draft. These are my first reflections, we should discuss this more in a tutorial. I look forward to seeing the next draft ahead of the next methods session.]

Steve second brief feedback

This is a very clear and well styled first draft. The description of the bread-making at the end tells the reader a great deal about your approach to making things and relating to others. The mode of address throughout is very well pitched.]