Puce Modern Moment: Camp, Postmodernism, and the Films of Kenneth Anger: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 40: | Line 40: | ||

http://www.wga.hu/art/m/michelan/1sculptu/pieta/1pieta1.jpg | |||

https://3.bp.blogspot.com/-4UAHgVyoiaY/VuD7iQqY3dI/AAAAAAAADqA/f_InESDyM74/s1600/Kenneth%2BAnger%2BFireworks%2Bsoldier%2Bcarrying.png | https://3.bp.blogspot.com/-4UAHgVyoiaY/VuD7iQqY3dI/AAAAAAAADqA/f_InESDyM74/s1600/Kenneth%2BAnger%2BFireworks%2Bsoldier%2Bcarrying.png | ||

Revision as of 16:31, 17 February 2017

NOT FINISHED

Puce Modern Moment: Camp, Postmodernism, and the Films of Kenneth Anger Vincent Brook (2006) Page 3: Puce Moment (1949) is a “lavorishly colored evocation of the Hollywood now gone, shown through an afternoon in the milieu of the 1920’s star” (text from the video box). The film was shot when Kenneth Anger was nineteen. The music by Jonathan Halper, was added in the 1970’s.

Through mobilizing the films of Kenneth Anger the writer tries to examine the historical, aesthetic, and ideological connections between camp and postmodernism. He hopes to broaden and enrich our understanding of these complex and still controversial cultural practices.

Puce Moment has a precocious (unusually advanced or mature in development) camp sensibility and postmodern consciousness according to Brook. Page 4: But camp was already mentioned in for example the sixteenth century England, where “camping” described young men who wore women’s costumes “in play” (Rogers, 40). Mae West who became a camp icon also noted. “When a character in the play is asked if anyone heard a scren, she responds, “No you heard them queens next door campin”. So Anger did not invent camp, but appears to have tapped an century-old tradition.

Brooke turns to the essay of Susan Sontag, Notes on Camp, to clarify his point on how Puce Moment was, original even revolutionary. In Notes on Camp (1964) Sontag already traces camp back to Italian mannerist paintings and rococo architecture. She differentiates two kinds of camp: “old” and “modern” camp. “Oldstyle camp, in Sontag’s scheme, disdained vulgarity and “sought rare sensations, undefiled by mass appreciation”; (hipster?) modern camp conversely, “relish[es] mass culture.”

One of modern camp’s key precepts is: “the equivalence of all objects”. “A correlative of this democratic this “democratic esprit” Sontag suggests is modern camp’s eclecticism. This is discoverable in the behavior of persons as well as in the quality of objects.” Page 4/5: “Other items on her list apply directly to Anger and his work: The Enquier tabloid newspaper (Anger’s book-length scandal sheet Hollywood Babylon); Aubrey Beardsley drawings (the opening titles to Anger’s Inauguration of the pleasure dome); the old Flash Gordon comics (a love of Anger’s that consciously informed many of his films; women’s clothes of the 1920’s – feather boas, fringed and beaded dresses, etc. (Puce Moment).” The film “Flaming Creatures” is for Sontag the defining moment in the modern camp sensibility, but was made in 1963. Puce Moment was made in 1949. Sontag didn’t include Anger’s body of work in her camp analysis. She does mention “Fireworks” but she notes that it is “about the beauties and terrors of homoerotic love”. But as Brook mentions “Fireworks (1947), is already replete with “modern camp” elements, as are the other of his pre-flaming creates films: Rabbit’s Moon (1950), Eaux D’artifice (1954).” Brook analyses Fireworks and other early works by Anger to “fill the “modern camp”” lacuna” in Sontag’s writing about camp. And through this analysis start to chart the connections between camp and postmodernism.

Fireworks:

As mentioned before, while certain camp elements are obviously present in Fireworks, Sontag left out the humor, ludic playfulness, the abrupt shifts in tone form the sublime to the ridiculous, and the essential theatricality and sense of artifice in her reference.

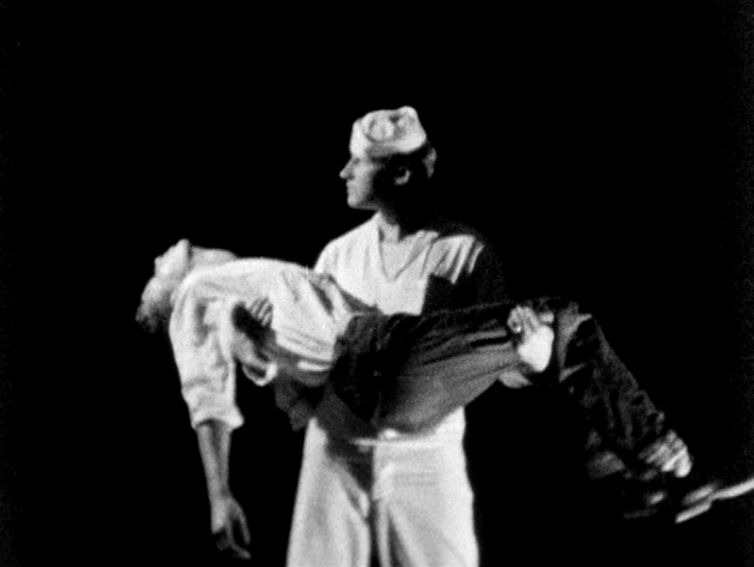

The film opens with a sailor holding a young man in Pieta-like pose. This pose is one of the most used poses/themes in art.

“the scene’s tableau-like quality is “explained” when the image reappears on a series still photos strewn on the floor beside the bed on which the young man is sleeping. As for the semiotics of the sailor, Anger explained in 1975: “ That’s a part of history now, but the sailor was a kind of sex symbol on one level, and on another level there was a great deal of ambivalence and hostility, and fear in the image.”

“In keeping with camp, this darker aspect is lace with low-brow humor.”

Other examples of the camp side of Fireworks show themselves in the play of words but also the double natured meaning of things like; milky substance that splatters on a man’s face, the explosions of the fireworks, an the phalic statue hidden under the bedsheets which at first seems to be an erection etc. etc.

Page 6: In Eaux D’artifice this double sense in which some things can be taken is demonstrated further. The title is a pun. Anger loves puns. Eaux d’artifice doesn’t exist in the french language. Homonymically it is an aural pun: “Ode to Artifice”. On the other hand, Feaux d’artifice means fireworks, so eaux d’artifice would be waterworks. “This linguistic act establishes an intriguing dialectic between Fireworks and Eaux D’artifice.” Which is also reflected in the fireworks in the water in the first film.