Puce Modern Moment: Camp, Postmodernism, and the Films of Kenneth Anger

Puce Modern Moment: Camp, Postmodernism, and the Films of Kenneth Anger

Vincent Brook (2006)

Page 3:

Puce Moment (1949) is a “lavorishly colored evocation of the Hollywood now gone, shown through an afternoon in the milieu of the 1920’s star” (text from the video box).

The film was shot when Kenneth Anger was nineteen. The music by Jonathan Halper, was added in the 1970’s.

Through mobilizing the films of Kenneth Anger the writer tries to examine the historical, aesthetic, and ideological connections between camp and postmodernism. He hopes to broaden and enrich our understanding of these complex and still controversial cultural practices.

Puce Moment has a precocious (unusually advanced or mature in development) camp sensibility and postmodern consciousness according to Brook.

Page 4:

But camp was already mentioned in for example the sixteenth century England, where “camping” described young men who wore women’s costumes “in play” (Rogers, 40). Mae West who became a camp icon also noted. “When a character in the play is asked if anyone heard a scren, she responds, “No you heard them queens next door campin”.

So Anger did not invent camp, but appears to have tapped an century-old tradition.

Brooke turns to the essay of Susan Sontag, Notes on Camp, to clarify his point on how Puce Moment was, original even revolutionary.

In Notes on Camp (1964) Sontag already traces camp back to Italian mannerist paintings and rococo architecture. She differentiates two kinds of camp: “old” and “modern” camp.

“Oldstyle camp, in Sontag’s scheme, disdained vulgarity and “sought rare sensations, undefiled by mass appreciation”; (hipster?) modern camp conversely, “relish[es] mass culture.”

One of modern camp’s key precepts is: “the equivalence of all objects”.

“A correlative of this democratic this “democratic esprit” Sontag suggests is modern camp’s eclecticism. This is discoverable in the behavior of persons as well as in the quality of objects."

Page 4/5:

“Other items on her list apply directly to Anger and his work: The Enquier tabloid newspaper (Anger’s book-length scandal sheet Hollywood Babylon); Aubrey Beardsley drawings (the opening titles to Anger’s Inauguration of the pleasure dome); the old Flash Gordon comics (a love of Anger’s that consciously informed many of his films; women’s clothes of the 1920’s

– feather boas, fringed and beaded dresses, etc. (Puce Moment).”

The film “Flaming Creatures” is for Sontag the defining moment in the modern camp sensibility, but was made in 1963.

Puce Moment was made in 1949. Sontag didn’t include Anger’s body of work in her camp analysis. She does mention “Fireworks” but she notes that it is “about the beauties and terrors of homoerotic love”.

But as Brook mentions “Fireworks (1947), is already replete with “modern camp” elements, as are the other of his pre-flaming creates films: Rabbit’s Moon (1950), Eaux D’artifice (1954).”

Brook analyses Fireworks and other early works by Anger to “fill the “modern camp”” lacuna” in Sontag’s writing about camp. And through this analysis start to chart the connections between camp and postmodernism.

Fireworks:

As mentioned before, while certain camp elements are obviously present in Fireworks, Sontag left out the humor, ludic playfulness, the abrupt shifts in tone form the sublime to the ridiculous, and the essential theatricality and sense of artifice in her reference.

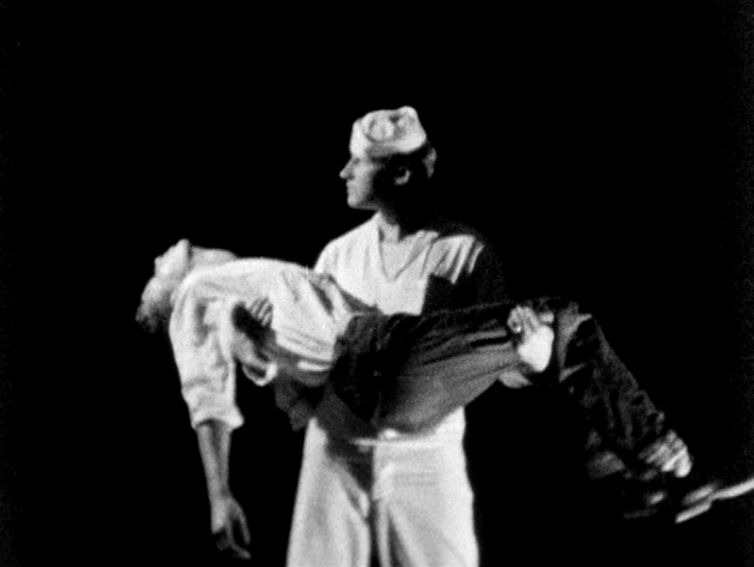

The film opens with a sailor holding a young man in Pieta-like pose. This pose is one of the most used poses/themes in art.

“the scene’s tableau-like quality is “explained” when the image reappears on a series still photos strewn on the floor beside the bed on which the young man is sleeping. As for the semiotics of the sailor, Anger explained in 1975: “ That’s a part of history now, but the sailor was a kind of sex symbol on one level, and on another level there was a great deal of ambivalence and hostility, and fear in the image.”

“In keeping with camp, this darker aspect is lace with low-brow humor.”

Other examples of the camp side of Fireworks show themselves in the play of words but also the double natured meaning of things like; milky substance that splatters on a man’s face, the explosions of the fireworks, an the phalic statue hidden under the bedsheets which at first seems to be an erection etc. etc.

Page 6:

In Eaux D’artifice this double sense in which some things can be taken is demonstrated further.

The title is a pun. Anger loves puns. Eaux d’artifice doesn’t exist in the french language. Homonymically it is an aural pun: “Ode to Artifice”. On the other hand, Feaux d’artifice means fireworks, so eaux d’artifice would be waterworks. “This linguistic act establishes an intriguing dialectic between Fireworks and Eaux D’artifice.” Which is also reflected in the fireworks in the water in the first film.One might also notice several conjunctions of fire and water – sailors, electric storm, matches, wharf, fireplace, flaming branches, milky substance, fire erections – that together suggest a dialectical interrelation of primal elements.

“Another association the title conjures, of course, is patently sexual: eaux d’orfice.”

Other camp elements are a woman played by a male small person, the clothes (baroque gown, and feathered headdress).

The film might be classified as High Camp, which always has an underlining seriousness. “You can’t camp about something that you don't take seriously. You’re not making fun of it: you’re making fun out of it. You’re expressing what’s basically serious to you in terms of fun and artifice and elegance.”

Modern camp accoring to Sontag:

“sensibility of failed seriousness”:

“The whole point of [modern] Camp is to destroy the serious. Camp is playful, anti-serious.”

“One an be serious about the frivolous, frivolous about the serious.”

“Eaux D’Artifice’s deflation of seriousness flows primarily from its sexual, or rather orgasmic context.”

Page 7:

Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome (1954)

- There have been at least four versions.

- Influenced by his involvement in paganism and Aleister Crowley

- Philosophy of Crowley was called Magick

- It was based on the principle of the “magick” ritual

- One could evoke the Magick spirits by various means (drugs, the use of occult objects and words etc.)

- “A Crowleyan tenet with particular relevance to Anger, and camp, is “The sacredness of sex, which makes a sacrament of sex”

Look into Richard Dyer

Page 8:

- “There is a long association between homosexuality and witchcraft, and fringe and outlawed cults provide a space for marginal or forbidden sexualities.” (Dyer) p 7 / 8

In the ‘original’ the reflexive Hollywood dimension is not presented, but “the pastiche of archetypal characters, ritualistic structure, and mass-cultural references are retained throughout the film’s multiple incarnations, as are other quintessential (= pure and essential essence of something) modern camp accoutrements such as garish costumes, mask-like make-up, and a sense of grotesquery.”

Page 9:

The transvestism on ample display in Inauguration as in Eaux D’Artifice is another definitive component of camp.

the carnavalesque and gay

“Scorpio Rising (1969) is “a twenty-eight-minute satire of and homage to the biker scene, based partly on gay porn magazines of the period, Scorpio also signals a shit from modern to postmodern camp”

Camp/Postmodernism

“The camp sensibility was rife (= common or frequent occurence) with postmodern tendencies. The former’s rampant eclecticism, sense of theatricality and artifice, and conflation of categories are all trademarks of the postmodern.”

Page 10:

Charles Jencks articulated the aesthetic principles of postmodernism in architecture in 1997 in a way that looks a lot like the points about camp mentioned aboth: “The style is hybrid, double-coded, based on fundamental dualities. Sometimes it stems from the juxtaposition of new and old… sometimes it is based on the amusing inversion of the old… and nearly always it has something strange about it. In short, a highly developed taste for paradox is characteristic of our time and sensibility”.

Some overlapping areas of camp and postmodernism: pastiche/collage of images, fragmentation of the subject, issues of class.

According to Anger himself, calls Scorpio Rising “a ‘high’ view of the Myth of the American Motorcyclist. The Power Machine seen as tribal totem, from toy to terror. Thanatos in chrome and black leather and bursting jeans.”

This description captures the symbiosis of barb and embrace, dread and desire, that epitomizes both camp and postmodernism.

“For good and/or ill, camp/postmodernism did more than just commodify ‘newness,’ it created a language of commodification that transcended concepts of old and new, that subsumed all tenses within the present: no more ‘was’ or ‘will be,’ only is.”

“Time, has been smashed–and with it, History. The postmodern condition, in Jameson’s famous formulation, exists “in a perpetual present, and in in a perpetual change that obliterates traditions.”

Page 12:

“Gay/straight, fanciful horrific, new/recycled, sacred/profane– all binary oppositions camped/postmodernized into oblivion. Add swastikas to the mix, as the bikers’ emblem, and morality appears to go up in smoke as well.”

Camp’s amoral tendencies did not go unnoticed by Sontag: “Camp is a solvent of morality. It neutralizes moral indignation, sensors playfulness… Camp taste is, above all, a mode of enjoyment, of appreciation – not judgment”

Page 13

Conclusion:

The author doesn’t want to conclude that camp and postmodernism cover the same areas. But sees a mor efundamental and extensive kinship between camp and postmodernism–as cultural category, historical phenomenon, and ideological positioning than has previously been acknowledged.