On media: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

Media technology as extension of the man or media as a replacement/exclusion of the man, as Baudrillard mentions. | Media technology as extension of the man or media as a replacement/exclusion of the man, as Baudrillard mentions. | ||

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/A_Mathematical_Theory_of_Communication | |||

---- | ---- | ||

Revision as of 20:23, 23 May 2015

Marshall McLuhan, ‘media are the intersecting points or interfaces between technologies, on the one hand, and bodies, on the other’.

Media technology as extension of the man or media as a replacement/exclusion of the man, as Baudrillard mentions.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/A_Mathematical_Theory_of_Communication

A ‘History’ of Search Engines: Mapping Technologies of Memory, Learning, and Discovery ¬ Richard Graham

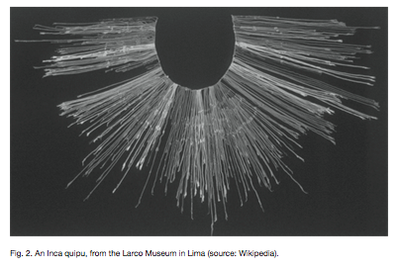

"To elaborate on the question of memory, I will now introduce a very old and culturally specific technology, the Quipu.

In ancient Andean South America, a particular technology called a Quipu was used in a number of different regions. This device, often described as talking knots, consisted of a thick cord from which a number of strings were suspended in the manner of a fringe. These strings were of different colors, according to the nature of the object each represented: for example, yellow stood for gold, red for the army, white for peace. The colors, being limited in number, had different meanings de- pending upon the general purpose and scope of the Quipu.

Quipus provided the basis for a more holistic process whereby memory was embedded in actions. The continued and repetitive use of the Quipu by many generations and in multiple regions allowed for change and adaptation but also solidi- fied links between different types of knowledge and behavior. Quipus were dynamic, they altered the way in which their users thought and remembered and the way that individuals and societies built up their identities.

Descriptions of the khipus contained in documents written at the time of the Spanish conquest (beginning in 1532) [which] reveal that the Inkas used khipus to record quantitative data (e.g., censuses and tribute records) as well as songs, genealogies, and other narrative forms containing historical information.

The exact way in which they were applied, however, is uncertain, due to their use in non-literate societies, which means no written account exists. Without a written record of their use, our historical knowledge of Quipus has become almost mystical, truly embedded within its own media.

The nature of remembering and forgetting using a Quipu necessarily undermines a complete understanding of how the technology worked. Quipus were used in a variety of different and fluid ways, and it was this plasticity of behaviors that changed the re- lationship between thought and knowledge for its users. On this note we return to search engines and the contemporary ways in which they are discussed. Although we cannot know the precise details of how the ancient Quipu technology was used, we know that even talking about the possible ways it might have been deployed allows us to interrogate the interplay between remembering and thinking. Could Quipus exist simply on a personal basis, did they need to be connected within an inter-medial field that took into account wider discourses? Is it inevi- table that a personal memory, when structured through shared media, transmutes into semi-shared codes? "