User:Quinten Swagerman/Graduation/Draft

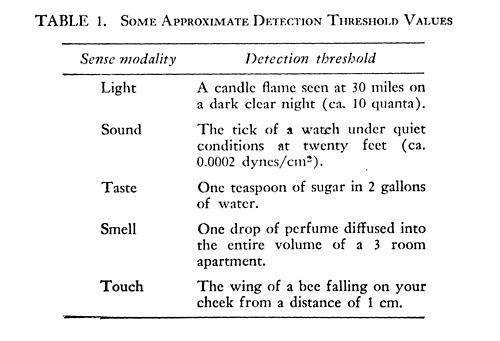

The table above has been taken from a 1962 article, written by the psychologist Eugene Galanther, named Contemporary Psychophysics. Psychophysics deals with the relation between stimuli and the perceptions they affect, and central to the field is the idea of the detection threshold. This is the point at which the probability of noticing something is as probable as not noticing it. The above table, then, gives one example of a detection threshold for every sense. When the wing of a bee falls on your cheek from a distance of one centimeter, chances are fifty percent that you just notice it. This wing is the weakest stimulus that can still be detected fifty percent of the time.

I first came across this table in the book Sensation & Perception by Jeremy Wolf et al. Wanting to learn more about visual perception, this introductory overview used at first year psychology courses seemed to be a good start. What first sparked off my interest was the concept of persistence of vision, mentioned briefly in a course on the history of film during my previous studies. Then there were some pleasantly useless facts picked up over the years: the area of visual information we consciously process per saccade is limited to about the size of your thumbnail on an extended arm. When you stand in front of a mirror and focus in turn on your left and right eye, you don't see our eyes move, even though they do (a friend watching can verify this). Knowing slightly more about visual perception now, it doesn't cease to be interesting. And for the graduation project, I'd like to immerse myself more deeply in this ubiquitous but quite mysterious phenomenon.

Parallel to this - and sometimes overlapping - runs an interest in optical toys, or pre-cinematic devices, or philisophical toys. The overlap is in that optical toys can serve very well to demonstrate properties of visual perception. In some cases the devices even came forth directly out of research into visual perception. The phenakistiscope, for example, was invented in the early 1830s by Belgian scientist Joseph Plateau, who had been studying retinal afterimages in the years before. Having worked with zoetropes, phenakistiscopes and flip books before, I noticed they tend to bring about a kind of wonderment. I think this is in part because of their transparancy. Film hides its workings, the operations taking place in a closed room behind the viewer. But with optical toys, the apparatus is as apparent as the content shown. The simple transparancy of a flip book or a zoetrope becomes an inherent part of the work.

I'd like to dive deeper in the two directions of perception and optical toys. Following these trajectories, something interesting might happen.

Previous work

The directions described above resonate to a greater or lesser degree in previous work. Here I'll describe three projects, of which two are flip books, and the third is concerned with modes of listening and the influence of visual information on the perception of sound.

One Page Flip

One Page Flip is a flip book – a little book which, when held in the left hand and flipped through with the right, shows an animation. The cover is white and on it it says in bold, black, capital letters: ONE PAGE FLIP

The book has 75 pages. On them: a thin black line-drawn animation of two hands flipping an empty flip book. One page is being flipped. In other words: within the span of flipping 75 pages, one page flips in the flip book within the flip book.

There's Nothing You Can't Do

There's Nothing You Can't Do is another flipbook. It shows in icon-like black and white illustrations: a roll of toilet paper unrolling while falling from a heighth, a foot landing on the roll of toilet paper, the lace of the shoe being pulled out, this lace being placed on the table in the form of an arrow, this arrow pointing to a glass, this glass being filled with water until it flows over the edge, a puddle forming around the glass, a drop from the puddle falling from the table, this drop being catched between a thumb and index finger.

The flip book came forth out of a well-defined assignment at Piet Zwart Institute. The end product had to be 1) a flipbook 2) based on the lyrics of the Jay Z song Empire State of Mind. And 3) every twenty pages the scene or central object should change with 4) the objects or scenes following from each other.

The title is taken from a prominent lyric in the refrain (In New York / Concrete jungle where dreams are made / There's nothing you can't do / Now you're in New York). Reacting to this sky-is-the-limit-ish statement, the flip book shows some things that one can indeed do, but in their smallness and nonsensicalness don't have the life-changing or life-enhancing consequences that the lyrics allude to.

Blip Listening

Blip Listening is a series of animations based on field recordings, to be seen on smartphones at the location where the sound was recorded. The animations are short, from 30 seconds to one minute and 30 seconds, and visualize one sound element from the recording in a minimal and abstract manner. For example: a white bar on a black background visualizes the bleep of a cash register in a supermarket At places in Rotterdam - zebra crossings, supermarkets, metro stations - translucent stickers are placed. On the sticker: a QR-code and one or more shapes. When the QR-code is scanned, the animation launches. The shapes on the sticker are now seen moving on the screen, visualizing one element from the field recording. This field recording might blend with the sounds of the environment, as an echo from the near past, particularly when the listener is wearing headphones and his volume isn't set too high.

The animations came forth out of an interest in experiencing places through sound. During idle moments – lying on my back in a park or sitting on the balcony - I sometimes found myself listening intensely, trying to hear as much as possible. The world unfolds in a different way when listening. Dziga Vertov puts it like this: 'One day in the spring of 1918… returning from a train station. There lingered in my ears the sights and rumble of the departing train… someone's swearing… a kiss… someone's exclamation… laughter, a whistle, the ringing of the station bell, the puffing of the locomotive… whispers, cries, farewells… And thoughts while walking. I must get a piece of equipment that won't describe, but will record, photograph these sounds.'

I aimed to create tiny reminders of the sounds surrounding us, and tried to point to this mode of listening that's not primarily practical (as in: a car horn warning you, someone's voice asking you if you feel like having pancakes for dinner).

Trajectory

I'd like to combine small experiments investigating optical toys with theoretical research on perception, pre-cinematic devices and the links between the two.

In learning more about perception, I will take the aforementioned book Sensation & Perception as my primary guide. This introduction to the subject gives a broad overview from various perspectives: psychology, biology, neuroscience, etcetera. The next step would be immersing myself more deeply in specific aspects of vision. Directions could be Gestalt psychology through the book Laws of Seeing by Wolfgang Metzger, the early study of afterimages through the work of Jan Purkinje, or the descriptions of proporties of (failing) vision by Oliver Sacks. Simultaneously I'll follow introductory cognitive psychology lectures at UvA.

I will investigate the history of optical toys through the collection and films of Werner Nekes and books such as A History of Pre-Cinema by Stephen Herbert. In giving a broader interpretation of the context of invention and what optical devices tell about the changes in visual culture at large, the books of Jonathan Crary could be useful. There are also interesting writings from a film studies perspective. André Gaudreault and Nicolas Dulac, for example, have written about repetition and the zoetrope.

Simultaneously and more practically, I will conduct a series of small experiments with optical toys. Through the making and changing of zoetropes, phenakistiscopes, ombro cinemas, praxinoscopes, etcetera, I'll aim to get to know their proporties, possibilities and limits.

By following these directions - at this point quite freely - I hope to arrive at interesting connections. This practice-and-research-intertwined hopefully then crystalizes in a more narrowly defined project before the new year commences.

For now, though, it might still be useful to speculate on some possible outcomes:

- Five looping projections, based on the table above. One for each sense, based on their descriptions, illustrating them or using them as a starting point for situations / small fictions.

- A big table, filled with moving objects / zoetropes / projections / shadows / mirrors (not unlike this) dealing with the phi phenomenon and beta movement.

- Illustrative animations of entoptic phenomena (visual effects whose source is the eye itself, such as floaters), projected inside spheres, the viewer having to peek inside the pupil of the sphere to see them.

- LCD-screen-based interactive zoetropes, with patterns and textures to be changed by the viewer with knobs (perhaps like Jasper van Loenen's Test Screen), based on forms derived from the study of afterimages. The tension between a unsophisticated, analog manner of creating motion and a very much sophisticated manner of creating static images could be interesting.

Notes

Currently reading:

- Sensation & Perception - Jeremy M. Wolfe - Sinauer, 2009

- Contemporary Psychophysics - Eugene Gallagher - New Directions in Psychology, 1962

- Oliver Sacks - The Mind's Eye - Picador, 2010

- God's Amateur - E.C. Large - Hyphen, 2010

- River Of Shadows - Rebecca Solnit - Penguin, 2004

- A History of Pre-Cinema - Stephen Herbert - Routledge, 2000

- Circularity and Repetition at the Heart of the Attraction - Nicolas Dulac & André Gaudreault - Amsterdam University Press 2006

To read:

- Nike Bätzner - Blickmaschinen / Visual Tactics - Dumont, 2008

- Mary Ann Doane - The Emergence of Cinematic Time - Harvard University Press 2002

- Jonathan Crary - Suspensions of Perception - The MIT Press 1999

- Jonathan Crary - Techniques of the Observer - The MIT Press 1990

- Laurent Mannoni - Eyes, Lies And Illusions - Lund Hemphries Publishers 2004

- Lisa Gitelman & Geoffrey Pingree - New Media 1740 - 1915 - MIT Press

- Harvey White - Floaters' in the eye - Scientific American 1962

- Maurice Merleau-Ponty - Phenomenology of Perception – Routledge 2005 (1st ed.: Gallimard, Paris 1945)

To see:

- Was geschah wirklich zwischen den Bildern? - Werner Nekes - 1987

- Der Lauf der Dinge - Peter Fischli & David Weiss - 1988

- The Children's Tapes - Terry Fox - 1974

Possibly drop in here: