User:Joca/essay The Ghost in the Speaker: Difference between revisions

| Line 20: | Line 20: | ||

<div style='max-width: 40rem; margin: 0 auto;'> | <div style='max-width: 40rem; margin: 0 auto;'> | ||

In a | In a significant number of science-fiction movies, the alternative role that is proposed is then that the robot takes the final lead and kills all humans on its way to keep its power. On the spectrum from servant to a killer with absolute power, there are many different roles to consider that give a conversational interface more agency. I would like to first discuss two speculative design projects on digital assistants that deal with this idea, before moving on to my metaphor smart speakers as spirited objects. | ||

With Foresight (2017) the designer David van Gelder de Neufville envisions a digital assistant that gets its agency based on the data and permissions given to it by its users. The system has a persona called Athena that helps its users, sometimes proactively pops up but also denies | With ''Foresight'' (2017) the designer David van Gelder de Neufville envisions a digital assistant that gets its agency based on the data and permissions given to it by its users. The system has a persona called Athena that helps its users, sometimes proactively pops up but also denies specific requests. For example when one of the family members closes down Athena's access to her agenda and private messages. | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

[[File:Foresight_02.jpg|400px|thumbnail|left| Foresight, with Athena as the holographic persona communicating with the user (Neufville, 2017)]] | [[File:Foresight_02.jpg|400px|thumbnail|left| Foresight, with Athena as the holographic persona communicating with the user (Neufville, 2017)]] | ||

<div style='max-width: 40rem; margin: 0 auto;'> | <div style='max-width: 40rem; margin: 0 auto;'> | ||

Based on information from social networks, smart light bulbs and private chats Athena observes what all family members did, are doing and will do. One of the questions that De Neufville asks here is if the assistant can create its | Based on information from social networks, smart light bulbs and private chats Athena observes what all family members did, are doing and will do. One of the questions that De Neufville asks here is if the assistant can create its reality using the data, and following that its awareness based on the knowledge and freedoms that it gained from its users. | ||

The idea of the bot as a companion is further researched in Karin Anders (2017), a speculative design research project by Karin Fischnaller that focuses on the digital assistant as an alter ego that could be a sparring partner for a designer. In her thesis she argues that the bot | The idea of the bot as a companion is further researched in Karin Anders (2017), a speculative design research project by Karin Fischnaller that focuses on the digital assistant as an alter ego that could be a sparring partner for a designer. In her thesis, she argues that the bot does not need to be a prosthesis, but can be a partner that brings in new ideas but also discusses the input brought in by the designer. The added value of the intelligence lies here in the collaboration between a human and a computer, that complement, and conflict with each other similar to normal social interactions. | ||

In her research, Fischnaller refers to the actor-network theory of the French philosopher Bruno Latour (Latour, 2005). He coins the term actants for non-human entities that | In her research, Fischnaller refers to the actor-network theory of the French philosopher Bruno Latour (Latour, 2005). He coins the term actants for non-human entities that can perform actions in the world and have a form of agency. For the context of smart speakers, I like how Jensen and Block (2013) elaborate on this idea by connecting the actants to Japanese Shinto-inspired techno-animism. In the Shinto religion, there is a focus on the idea that things change form from non-human to human, from the real-world to the other world. Spirits inhabit living creatures, but also natural objects. Techno-animism extends this idea to electronic devices. | ||

Another school of thought that connects to this idea is the techno-Buddhism represented by the pioneering robot scientist Masahiro Mori. In the 1980's he wrote The Buddha in the Robot (Mori, 1981), where he states that ' (...), there is no master-slave relationship between humans and machines. The two are fused in an interlocking entity. (...) Man achieves dignity by recognizing the same Buddha-nature that pervades his own.' Like other traces of religion in Japan, these ideas are not applied in a strict religious way by most people. It's use is more socially constructed and seen as a way to maintain order and do good. (Kawano, 2005) | |||

After World-War II the government and industry tried to get widespread acceptance for robots, by pointing out the relations of these to traditional Japanese culture. (Ito, 2007) In comparison to robotics researchers in the West that worked with a more functionalist approach, in Japan the Buddist- and Shinto-inspired researchers were more influential because of this development. (Vallverdú, 2011) Unlike what if often thought, this does not result in Japan having a special relationship with robots. However, it results in a public perception that is slightly more receptive and realistic about the role of robots in society as cross-cultural studies show. (Bartneck et al., 2015) | |||

Given the state of technology at the moment, the idea of a spirited speaker is of course a metaphor. It might get more realistic in the future | As a metaphor for smart speakers, I find the idea of spirited technology useful, because techno-animism relies on the idea of space and material. The intelligence is not flowing freely in the space but can live in a device like a smart speaker. Another interesting aspect in contrast to functionalist thinking about non-human creatures is that these 'spirits' do not necessarily have a backstory that explains their behavior. | ||

The spirit in a speaker might be a ghost that has much knowledge thanks to its internet connection, but on the other hand, it is not able to move out of the speaker. Sometimes it is willing to help its user, but sometimes it needs your help to do something. As these ghosts are bound to their device, the different speaker features different ghosts that have their distinct personality. | |||

Within this metaphor, the speaker is intelligent and might have a certain degree of conscience, but at the same time, it is unable to do some things that humans are capable of. It becomes a mysterious object with a degree of agency that users can discover by a conversation with it. | |||

Given the state of technology at the moment, the idea of a spirited speaker is, of course, a metaphor. It might get more realistic in the future like the Mechanical Turk was an early vision of a chess computer like Deep Mind, but the metaphor serves mainly a different goal: it is a way to envision an exchange between people and conversational interfaces that is somewhere in between voice commands, and social conversation. | |||

====The speaker as a player==== | ====The speaker as a player==== | ||

Revision as of 12:39, 28 March 2019

III - The Ghost in the Speaker

Embracing characters in conversational interfaces

Should we be kind to our smart assistants? In Why'd You Push That Button, a podcast about the social dynamics around technology a mother of a six-year-old gives the following answer to this question: 'We really want him to understand them that you have conversations with people and how you have them. Having a robot or a smart assistant that will answer to you no matter how you speak with them, well that is not life, even though it is life, but it is not real life.'

The slight confusion in this quote gives a hint of the power of conversational interfaces to give the illusion of consciousness, even just by the use of audio. The examples in the first chapter show that sound is a medium that can express character, as was typically done in radio and broadcast. The Interactivity of a smart speaker allows for a different kind of storytelling. In the context of journalism, it might fit a slower type of news than is typically done now with the news briefings on smart speakers.

This potential is not used at the moment for various reasons: one is the lack of content specifically designed for consumption on speakers. (Newman, 2018) On the other hand, the smart speaker is a new medium, which starts with presenting old media as its content before it develops its own genres (McLuhan, 2002).

On the other hand, the space to experiment with content forms is somewhat limited by the way these conversational interfaces are positioned in the market. The dominant platforms are designed to create assistants that act after user commands. They are designed as an efficient tool, rather than a way to enrich 'our own capacities to think, feel and act' as formulated by Brenda Laurel in her thoughts on interfaces in the book Computers as Theatre (2013).

In this chapter I want to speculate on a interaction design for a smart speaker that allows for a different way of storytelling. Starting from the role and character of the speaker to give it more agency than an assistant. Then I elaborate on what this means for how these speakers could act in a conversation, using the ideas of Computers as Theatre in the context of smart speakers. Then I conclude with different possibilities to present news on smart speakers using these ideas from a more realistic, to more speculative scenarios.

The speaker as a spirited object

To broaden the possibilities for interactions between humans and conversational interfaces like smart speakers, it helps to consider a different role than the one of a virtual assistant, because of the constraints that are part of the master-slave relationship connected to it.

In a significant number of science-fiction movies, the alternative role that is proposed is then that the robot takes the final lead and kills all humans on its way to keep its power. On the spectrum from servant to a killer with absolute power, there are many different roles to consider that give a conversational interface more agency. I would like to first discuss two speculative design projects on digital assistants that deal with this idea, before moving on to my metaphor smart speakers as spirited objects.

With Foresight (2017) the designer David van Gelder de Neufville envisions a digital assistant that gets its agency based on the data and permissions given to it by its users. The system has a persona called Athena that helps its users, sometimes proactively pops up but also denies specific requests. For example when one of the family members closes down Athena's access to her agenda and private messages.

Based on information from social networks, smart light bulbs and private chats Athena observes what all family members did, are doing and will do. One of the questions that De Neufville asks here is if the assistant can create its reality using the data, and following that its awareness based on the knowledge and freedoms that it gained from its users.

The idea of the bot as a companion is further researched in Karin Anders (2017), a speculative design research project by Karin Fischnaller that focuses on the digital assistant as an alter ego that could be a sparring partner for a designer. In her thesis, she argues that the bot does not need to be a prosthesis, but can be a partner that brings in new ideas but also discusses the input brought in by the designer. The added value of the intelligence lies here in the collaboration between a human and a computer, that complement, and conflict with each other similar to normal social interactions.

In her research, Fischnaller refers to the actor-network theory of the French philosopher Bruno Latour (Latour, 2005). He coins the term actants for non-human entities that can perform actions in the world and have a form of agency. For the context of smart speakers, I like how Jensen and Block (2013) elaborate on this idea by connecting the actants to Japanese Shinto-inspired techno-animism. In the Shinto religion, there is a focus on the idea that things change form from non-human to human, from the real-world to the other world. Spirits inhabit living creatures, but also natural objects. Techno-animism extends this idea to electronic devices.

Another school of thought that connects to this idea is the techno-Buddhism represented by the pioneering robot scientist Masahiro Mori. In the 1980's he wrote The Buddha in the Robot (Mori, 1981), where he states that ' (...), there is no master-slave relationship between humans and machines. The two are fused in an interlocking entity. (...) Man achieves dignity by recognizing the same Buddha-nature that pervades his own.' Like other traces of religion in Japan, these ideas are not applied in a strict religious way by most people. It's use is more socially constructed and seen as a way to maintain order and do good. (Kawano, 2005)

After World-War II the government and industry tried to get widespread acceptance for robots, by pointing out the relations of these to traditional Japanese culture. (Ito, 2007) In comparison to robotics researchers in the West that worked with a more functionalist approach, in Japan the Buddist- and Shinto-inspired researchers were more influential because of this development. (Vallverdú, 2011) Unlike what if often thought, this does not result in Japan having a special relationship with robots. However, it results in a public perception that is slightly more receptive and realistic about the role of robots in society as cross-cultural studies show. (Bartneck et al., 2015)

As a metaphor for smart speakers, I find the idea of spirited technology useful, because techno-animism relies on the idea of space and material. The intelligence is not flowing freely in the space but can live in a device like a smart speaker. Another interesting aspect in contrast to functionalist thinking about non-human creatures is that these 'spirits' do not necessarily have a backstory that explains their behavior.

The spirit in a speaker might be a ghost that has much knowledge thanks to its internet connection, but on the other hand, it is not able to move out of the speaker. Sometimes it is willing to help its user, but sometimes it needs your help to do something. As these ghosts are bound to their device, the different speaker features different ghosts that have their distinct personality.

Within this metaphor, the speaker is intelligent and might have a certain degree of conscience, but at the same time, it is unable to do some things that humans are capable of. It becomes a mysterious object with a degree of agency that users can discover by a conversation with it.

Given the state of technology at the moment, the idea of a spirited speaker is, of course, a metaphor. It might get more realistic in the future like the Mechanical Turk was an early vision of a chess computer like Deep Mind, but the metaphor serves mainly a different goal: it is a way to envision an exchange between people and conversational interfaces that is somewhere in between voice commands, and social conversation.

The speaker as a player

When a smart speaker has the persona of a ghost that lives in the speaker, the next question is then what this means for interaction with users. And how these characteristics of the medium can be used for more interesting ways of publishing news on these devices.

In the media equation (Reeves and Nass, 1996) the authors argue that interactions of humans and computers are similar to social interactions. Media equals real life, and in our use of media the same social codes apply as in interactions with other people. The illusion of some form of intelligence and autonomy could be enough to make people believe it. The ideas of Brenda Laurel in Computers as Theatre (2013) connect well to this idea. In the book Laurel uses theatre as a model for interaction design. When the first edition was published in the '90s, Laurel's intended applications were originally games, or virtual reality. The idea of the interface as a player is however particularly useful for a smart speaker, because of the importance of conversation and character that it has in common with theatre.

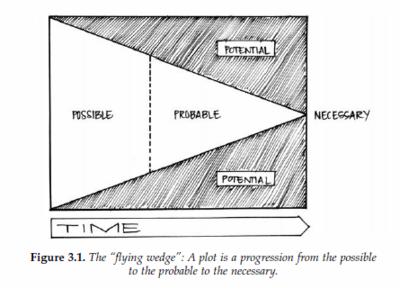

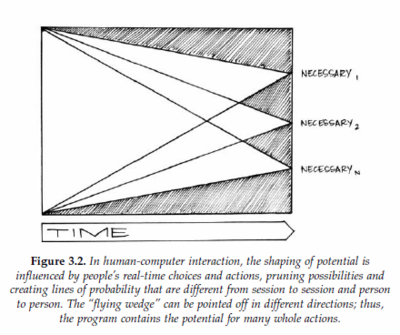

Laurel shows that human-computer interactions work as a a organic whole, and that they feature dramatic structural characteristics. Like a playwright, an interaction designer creates a space for possible actions, where the design of objects, characters and environments serves this a goal. Choices for, or by people using a computer can make particular situations more probable to happen. Interaction should be made clear in the context of the representation: sources of agency are represented explicitly, using the characters that are part of the 'play', and so are the objects, environment and the potential of all these items.

Implications for storytelling

For a smart speaker that tells a news story, there a multiple ways to incorporate this vision. In line with the current news briefings done by speakers, I imagine that instead of one universal assistant that reads a 'one-size fits all' overview of headlines, people could choose a particular character that fits the view on news they want. Imagine a speaker that treats celebrity news like the presenter of a entertainment news show. It would pick news from more popular sources, feature a lot of audio effects that create the energy typical for these kind of shows and maybe ask you in the end for your feelings about the newest dress of Kim Kardashian.

Are you more interested in the social dynamics behind the influence of celebrities on popular culture? Then a speaker that is modelled after a media critic might be a better choice. This speaker will prefer background pieces about the role of celebrities, focusing more on the culture set by Kim Kardashian instead of her newest dress. It could ask about your opinion on the topic, and present articles that support or conflict with that. The formgiving of the audio is more calm and sober for this speaker.

Both speakers do not pretend to offer a full view on the world. What they do however is situate their news selection and presentation by attributing their sources, incorporating certain modes of reading and sound design that make their character more explicit to the user. When pieces are more specifically designed for speakers as a medium, it is possible to take this idea further in a scenario that looks more like a play.

Imagine that you put the entertainment speaker and the media critic speaker next to each other, and that they would tell the story together. One speaker could start with arguing that celebrities are role models for the general public, and the other speaker illustrates that with the latest headlines. In this exchange the power shifts from one speaker, to the other, to the user and back.

The authorship for these scenarios could be approached in different ways. Heavily scripting all interactions, with a more constraint choice for the people using the smart speaker, is a mode of working used by the Quartz bots mentioned in chapter 2. As technology progresses it is possible to have more parts of the story, questions to the user and included sounds generated. In this situation the authorship is shared by the interaction designer and a journalist, that define a set of rules and content that fits the story, and the people using the speakers to discover various 'states' of the story.

The idea of seeing smart speakers as spirited devices that are actors in a play might sound a bit esoteric. However, it is possible to identify aspects of this idea in current speakers. As strongly as some may argue that digital assistants are tools that shouldn't have character, the Google Assistant actually has a detailed backstory: She comes from Colorado, loves kayaking and is the daughter of a research librarian, tells James Giangola, a lead conversation and persona designer for Google Assistant in an article on The Atlantic. To finetune the personality, the big players are eager to hire storyboard artists and persona designers from different film studios in Hollywood. (Schulevitz, 2018)

In that sense, the ideas expressed in this chapter elaborate on the importance of character and agency for more interesting and meaningful interactions with conversational interfaces like smart speakers. However, instead of using the personality to dress up an existing function like getting the latest headlines, I see potential in using the character and conversational skills of a smart speaker as the starting point for designing stories on this medium.

While making this point I conveniently put aside important aspects like technical feasability, or the businessmodel behind such a platform. The reason mainstream smart speaker work and look like they do now, is because Amazon sees it as an extra portal to their ecommerce platform, and Google as an extra way to collect data and further develop their Articifial Intelligence applications. At the same time, the idea of the conversational interface as a supercharged assistant started as a dreamy idea in movies, books and texts like the one you are reading.