Luis' Text on Practice 2022: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 22: | Line 22: | ||

Questioning my idea of working with migrant children has been an endless quest. From collaborative portraits to participatory photography classes, and more recently centering listening as the center of the creation of films. There are too many worries, implications, risks of portraying their lives, and it takes me long discussions with myself and others in order to feel at peace with my decisions. But these are questions I am making disregarding the children I am working with, the ones confiding me with memories of struggle. Why did I look for this? Why do I need to make people characters for my projects? Once children, such as Angel, have shared with me these important parts of his life, how will I share them without exploiting his trauma? | Questioning my idea of working with migrant children has been an endless quest. From collaborative portraits to participatory photography classes, and more recently centering listening as the center of the creation of films. There are too many worries, implications, risks of portraying their lives, and it takes me long discussions with myself and others in order to feel at peace with my decisions. But these are questions I am making disregarding the children I am working with, the ones confiding me with memories of struggle. Why did I look for this? Why do I need to make people characters for my projects? Once children, such as Angel, have shared with me these important parts of his life, how will I share them without exploiting his trauma? | ||

I have | In order not to get paralyzed, I have realized that understanding and accepting the ethical challenges involved is not something to be resolved in order to then get on with the production of art, it is the work itself (Goldbarg, Matarosso, 2021, p.8). I expect one question to persist and guide me throughout my research: how can I ethically facilitate migrant children to represent the violence they have lived? | ||

Revision as of 18:56, 6 June 2022

Both my recent and my current work revolve around participative film projects with children in a context of forced migration. My recent work was done in a shelter in my home city of Chihuahua, Mexico, and my current work is the preparation of a project in the upcoming months both with an organization in Calais, France and in a shelter in Queretaro, Mexico. My most recent work is ‘the boy in the abandoned house’, a film that shares my encounter with forcibly displaced children living in a shelter in the city of Chihuahua, Mexico. The aim was to create a participatory film.

When I began this project, I asked the children what kind of movie they wanted to make, and they chose to do a horror movie. Angel, a pre-adolescent boy from Honduras, became the protagonist of the project right away. He surprised people with his inventiveness, he could lighten up spaces with his spontaneous rap bits and he was vocal about the violence he lived through in his journey. Horror films happened to be his favorite genre, and we shot many hours of conversations planning the film. Through and around conversations about the plot of the film I compiled adverse memories of his journey. I initially told Angel that I was making a documentary film sharing how we were making a horror movie together and that I would use the voice recordings to remember all the things I learned from him. He told me it was fine as long as he could not be identified. After some weeks in which we discussed and worked on the script, he left before we could finish it. I am currently finalizing the editing process where I mix scenes from the screenwriting process and pre-production of the participatory film we never managed to get started. This short film will be about how creation and experiences in this context are subject to the underlying forces of migration beyond control. A film about the possibilities of creation in the most adverse situations.

My current work expands my participatory art practice further by facilitating medium and long term workshops with children who have migrated or are currently on the move both in Mexico and France. I have consolidated a collaboration with two different NGOs, in Mexico and in France, in order to implement this project. I plan to work a 4 month long program both remotely and on location this summer in Mexico. I have to deal with different uncertainties, firstly the freedom of work and specific parameters I will get from institutions I have not worked with before, and most importantly, in motivating the migrant children and tutors to participate.

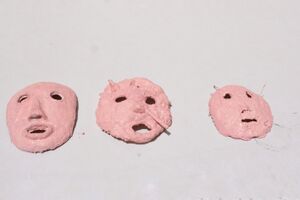

The project aims to document the art classes for children I will facilitate at the shelters and the production of a participatory horror short-film. Children will be taught storytelling frameworks and filmmaking techniques, and I will fill the technical gaps where needed. The lines between their own films and my documentary will diffuse, as well as scenes of fiction and nonfiction. I will also facilitate art therapy classes, during which the children will be encouraged to make handmade masks to conceal their identity during the film. For this, I will draw from my years of practice teaching photography in Mexico, and I am also researching the experiences and methodologies of film educational projects such as Common Frames in the Netherlands, and Cinema en Curs in Spain.

My intention with the pedagogical work that I carry out, document and share with this population is to generate impacts on the collective imagination on issues as complex as discrimination against people in the context of global mobility. I believe in the potentiality of children to become historical subjects, and collective protagonists of necessary social transformations, of migration as a decolonial process. They have taught me to see them as creators of their own lives and projects, in times when modernity considers them disposable, and despises their desires, thoughts, acts, and historicity.

For this reason, this year I have been expanding my theoretical framework and critical reflection. I am currently researching topics about ethics, art therapy, decoloniality, participatory art, and filmmaking. With both my recent and current work, comes the questions I want to keep exploring: how can I avoid a participatory work that ends up being exploitative? How can I design a co-creation dynamic with children that both acknowledges the unbalanced power relation and follows an equality principle? How can this process adapt to the real needs and desires of children migrating?

My current work is similar to my recent one as it is also collaborative in nature and it intends to involve children to have a central role in the decision making from the script writing to the editing of the film. It initially integrated perspectives of children in Mexico and in a second phase it will be further continued in Europe. As opposed to most related projects and media representations, in these films migration is not directly discussed nor the personal stories of the children. The migration context can be felt in a subtle way throughout and how it affects the unexpected unfolding of the narrative.

I next want to focus on long term collaborations. For this, I want to both find participants that will commit for a process lasting several months in the case of Mexico, and in the case of France, I will move there for three months to also create a stable co-creation dynamic. I want to have clearer general working principles, such as equality (as a working principle) and shared authorship in the decisions, and on the other hand have a process, and thus its products, more open to change arising from the application principles. I also am planning on setting up dynamics that might open new explorations such as creating a narrative that binds together two different groups of people in different regions of the world, and coediting the documentation of the process alongside their participants.

Thinking about the end result of this project, I have two goals that are important in pedagogic art projects: the production of a dynamic experience for children participating and the production of a complex artistic film that engages an external audience (Bishop, p.246, 2012). Facing the uncertain nature of participatory projects (as in a horizontal process in which I gather with children to decide to do an undefined product under a certain framework), I think next semester, once I have documentation and facilitated artworks, I will need to discuss challenges in the development, edit and presentation of the work with the different tutors at the Piet Zwart Institute.

I hope to be part of projects where art is both part of a social change and a reflection of it. I wish I could find a way in which the more pressing material needs could really be met by people that are forcibly displaced. I am starting through education, but I hope I can create projects that follow the line of “useful art”, such as Tania Bruguera’s Arte de Conducta course in Cuba. I think there are multiple overlaps that participatory art, educational projects and even legal action can potentially serve participants. Through this perspective I want to acknowledge and mitigate the risk of presenting a participatory spectacle that will ultimately benefit my career but does not truly challenge anything nor leaves a lasting benefit for the children participating (Beshty, 2015).

Questioning my idea of working with migrant children has been an endless quest. From collaborative portraits to participatory photography classes, and more recently centering listening as the center of the creation of films. There are too many worries, implications, risks of portraying their lives, and it takes me long discussions with myself and others in order to feel at peace with my decisions. But these are questions I am making disregarding the children I am working with, the ones confiding me with memories of struggle. Why did I look for this? Why do I need to make people characters for my projects? Once children, such as Angel, have shared with me these important parts of his life, how will I share them without exploiting his trauma?

In order not to get paralyzed, I have realized that understanding and accepting the ethical challenges involved is not something to be resolved in order to then get on with the production of art, it is the work itself (Goldbarg, Matarosso, 2021, p.8). I expect one question to persist and guide me throughout my research: how can I ethically facilitate migrant children to represent the violence they have lived?