User:Joca/the-non-human-librarians: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

(Changed location of <onlyinclude></onlyinclude> for the sanity of the IFTL page. If you use automated references with <ref>Cochior, C. (2016). IN THE COMPANY OF BOTS ...</ref>, the reference would show up on each page your page is included in!) |

||

| (10 intermediate revisions by one other user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[File:Clippy legacy.jpg|thumbnail|left| | = Project description = | ||

<onlyinclude> | |||

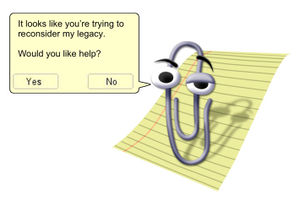

[[File:Clippy legacy.jpg|thumbnail|left|Clippy asking to reconsider his legacy (Feldman, 2016)]] | |||

XPPL's non-human librarians are a collection of bots that serve as an interface for maintaining the collection and discovering interesting items. The bots interact in a playful way with the users of the library, sometimes helping people, but also demanding attention for their work and fighting with the users. Each bot is responsible for one activity. These vary from crawling the collection with strange combinations of queries (e.g. Scanned pdf, orange cover, published in Slovenia) and highlight them on the frontpage, to making stacks of books that have never been downloaded. And these jobs can go as far as offering non-sensical autocomplete suggestions in the searchbar. A bot can even chase users with pop-ups to force them to add metadata after spending too much time in the XPPL without contributing books, stacks, or annotations. | |||

The working methods of this swarm of bots balance between offering a satyric view on algorithmic assistances and supporting people in contributing to the | The working methods of this swarm of bots balance between offering a satyric view on algorithmic assistances and supporting people in contributing to the XPPL and its community. A well-known example of bots that maintain a website and collaborate with humans are the anti-spam bots made for Wikipedia. In ''In the Company of Bots'' (2016) Christina Cochior describes this relation as operating "at the intersection of technical infrastructure and social superstructure". The XPPL bots try to challenge the traditional social role of the bot as an assistant.</onlyinclude> | ||

Each bot is a script that performs a specific task. It works periodically, or it is activated by specific actions of users; think of typing in the search bar for example. Then it will request information form the library catalog, using the application programming interface (API) offered by the infrastructure of the | Each bot is a script that performs a specific task. It works periodically, or it is activated by specific actions of users; think of typing in the search bar for example. Then it will request information form the library catalog, using the application programming interface (API) offered by the infrastructure of the XPPL. The bot processes the data, for instance by pairing a book title with meta data provided by an external service. The result can be part of the interface in the form of a highlighted book, dialogbox showed to the user, or even be sent back to the catalog as additional data that part of an item in the collection. | ||

The project builds upon the research I did for the past special issue. I looked into ways how computers read text and structure the found information. Besides that, I made a reader the profession of librarianship, where the role of serving users already started at the start of the first librarian school (Dewey, 1886). The | The project builds upon the research I did for the past special issue. I looked into ways how computers read text and structure the found information. Besides that, I made a reader the profession of librarianship, where the role of serving users already started at the start of the first librarian school (Dewey, 1886). The XPPL offers an interesting context to experiment with the role of the librarian in a digital pirate library. | ||

The bots live as elements of the 'default' library interface. In addition to the curation by 'human librarians' in the stacks, the non-human librarians offer a way to explore to explore the collection in a programmatic way. Another use of the bots within the | The bots live as elements of the 'default' library interface. In addition to the curation by 'human librarians' in the stacks, the non-human librarians offer a way to explore to explore the collection in a programmatic way. Another use of the bots within the XPPL is to visualize the invisible work required to maintain the library, nudging people to add metadata to the collection. It raises interesting questions about what it takes to keep the collection useful on the long term, and what it means to collaborate with bots that sometimes tend to use their masters as their human assistants to complete their work. | ||

''References'' | |||

* Cochior, C. (2016). IN THE COMPANY OF BOTS. | * Cochior, C. (2016). IN THE COMPANY OF BOTS. Available at: http://www.randomiser.info/project/inthecompanyofbots.html | ||

* Dewey, M. | * Dewey, M. (1886). ''Librarianship as a profession for college-bred women. An address delivered before the Association of collegiate alumnæ, on March 13, 1886''. Library bureau, Boston. | ||

* Feldman, B. (2016 | * Feldman, B. (2016). [Clippy asking to reconsider his legacy] [digital image]. Available at: http://nymag.com/vindicated/2016/10/clippy-didnt-just-annoy-you-he-changed-the-world.html | ||

Latest revision as of 11:15, 24 May 2018

Project description

XPPL's non-human librarians are a collection of bots that serve as an interface for maintaining the collection and discovering interesting items. The bots interact in a playful way with the users of the library, sometimes helping people, but also demanding attention for their work and fighting with the users. Each bot is responsible for one activity. These vary from crawling the collection with strange combinations of queries (e.g. Scanned pdf, orange cover, published in Slovenia) and highlight them on the frontpage, to making stacks of books that have never been downloaded. And these jobs can go as far as offering non-sensical autocomplete suggestions in the searchbar. A bot can even chase users with pop-ups to force them to add metadata after spending too much time in the XPPL without contributing books, stacks, or annotations.

The working methods of this swarm of bots balance between offering a satyric view on algorithmic assistances and supporting people in contributing to the XPPL and its community. A well-known example of bots that maintain a website and collaborate with humans are the anti-spam bots made for Wikipedia. In In the Company of Bots (2016) Christina Cochior describes this relation as operating "at the intersection of technical infrastructure and social superstructure". The XPPL bots try to challenge the traditional social role of the bot as an assistant.

Each bot is a script that performs a specific task. It works periodically, or it is activated by specific actions of users; think of typing in the search bar for example. Then it will request information form the library catalog, using the application programming interface (API) offered by the infrastructure of the XPPL. The bot processes the data, for instance by pairing a book title with meta data provided by an external service. The result can be part of the interface in the form of a highlighted book, dialogbox showed to the user, or even be sent back to the catalog as additional data that part of an item in the collection.

The project builds upon the research I did for the past special issue. I looked into ways how computers read text and structure the found information. Besides that, I made a reader the profession of librarianship, where the role of serving users already started at the start of the first librarian school (Dewey, 1886). The XPPL offers an interesting context to experiment with the role of the librarian in a digital pirate library. The bots live as elements of the 'default' library interface. In addition to the curation by 'human librarians' in the stacks, the non-human librarians offer a way to explore to explore the collection in a programmatic way. Another use of the bots within the XPPL is to visualize the invisible work required to maintain the library, nudging people to add metadata to the collection. It raises interesting questions about what it takes to keep the collection useful on the long term, and what it means to collaborate with bots that sometimes tend to use their masters as their human assistants to complete their work.

References

- Cochior, C. (2016). IN THE COMPANY OF BOTS. Available at: http://www.randomiser.info/project/inthecompanyofbots.html

- Dewey, M. (1886). Librarianship as a profession for college-bred women. An address delivered before the Association of collegiate alumnæ, on March 13, 1886. Library bureau, Boston.

- Feldman, B. (2016). [Clippy asking to reconsider his legacy] [digital image]. Available at: http://nymag.com/vindicated/2016/10/clippy-didnt-just-annoy-you-he-changed-the-world.html