User:Zalán Szakács/thesis1chapter

Chapter I

Imaginary & Real

Uncanny

Uncanny is surrounding us in every aspect of our life and our society. The notion and the feeling of this phenomenon could be traced back to the existence of humankind. To understand this experience, first I would like to examine the ethnology of it described in Merriam-Webster dictionary:

uncanny:

a: seeming to have a supernatural character or origin: eerie, mysterious

b: being beyond what is normal or expected: suggesting superhuman or supernatural powers. 2

Secondarily I would like to address it from the psychological perspectives described by Sigmund Freud in his 1919 essay “Uncanny”: “Animism, magic and witchcraft, the omnipotence of thoughts, man’s attitude to death, involuntary repetition and the castration-complex comprise practically all the factors which turn something fearful into an uncanny thing.” 3 (Freund, 1919) He aimed to understand this subject from the purest human point of view by ignoring the ego and focussing on the subconsciousness. We appear to encounter the ‘‘uncanny’’ in conjunction with the ‘‘survival of primitive ideas,’’ the resurfacing of infantile conceptions of life that the rational adult imagines have been overcome. These include belief in the existence of supernatural destructive forces, the return of the dead or contact with them, all of which belong to the doctrine of animism. According to Freud, the uncanny results from the contradiction between what we think we know and what we fear we perceive at a particular moment. 4 (Grau, 2007)

Certainly, many people in the nineteenth century spoke of the "phantoms of the brain" as though they came from outside-as if there were, at the very heart of subjectivity itself, something foreign and fantastic, a demonic presence from elsewhere, a specter-show of unaccountable origin. By the time of Freud, the rhetorical pattern had resolved, as it were, into a cultural pathology: everyone felt "haunted." That is to say, the mind itself now seemed a kind of supernatural space, filled with intrusive spectral presences-incursions from past or future, ready to terrify, pursue, or disable the harried subject. 5 (Castle, 1988) Murray Leader is recalling Tom Gunning words in his book The Modern Supernatural and the Beginnings of Cinema, that not all uncanny experiences are optical (or sensory at all) and that the optical uncanny is not strictly modern. Nonetheless, he holds that “in modernity not only does the optical uncanny become crucial and dramatic, but the modern scientific and technological exploration of vision and optics (such as the proliferation of new optical devices) multiply and articulate the possibilities of the optical uncanny”. It is in this compulsive focus on seeing—on seeing things that may or may not be there—that we can recognize one powerful connection between the supernatural and early cinema. 5a (Murray, 2017)

Gods and Ghosts

During ancient Greece and Roman times, the most successful and most common magic was practiced with the plane and concave mirrors. The projections of gods and ghosts took in temples and places of worship place, and described in 1829 by the French scholar Bacconiere-Salverte in his book The Occult Sciences. 6 Hermann Hecht is stating in his 1983 written article, “The History of Projecting Phantoms, Ghosts and Apparitions” that, concave mirrors were in fact used for projection purposes. Here he is referencing to the Jewish story of the Witch of Endor, who summoned before King Saul the ghost of the prophet Samuel. (1 illustration) A Jewish tradition says, that ghosts always appear standing on their heads, which would be of course be the case if concave mirrors were used without the image being reinverted. 7 Paradoxically the appearance of Samuel cannot be true, because he appeared before Saul standing on his feet! The anonymous author of the book The Wonders of Light and Shadow written in 1851 thinks, that “apparitions of heathen gods” were achieved by a form of magic lantern rather than mirrors, because of the logistical difficulties of setting up the latter. 8 ‘Gods’ were temple workers appearing from hidden corners under the cover of smoke from the altar fires. 9 (2 illustration)

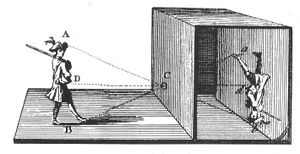

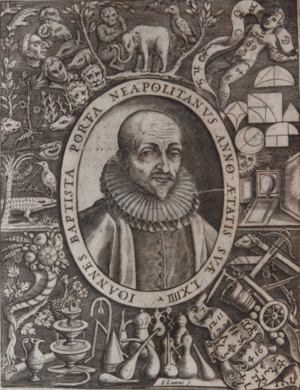

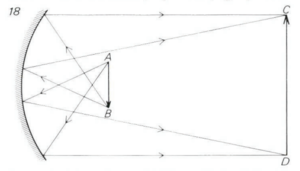

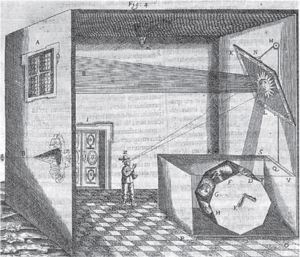

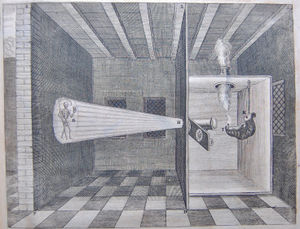

Writing about ghost and devil projection instruments I would like to stress out the influential characteristics of camera obscura. This apparatus allowed in its simplest form to project images through an aperture, upside down on a surface opposite the hole. (3 illustration) Giovanni Battista Della Porta (4 illustration) revolutionized in 1589 the use of the lenses and projected the picture the right way round, above the aperture, by fixing a concave mirror inside the camera to reinvert the image. 10 The mirror reflects an enlarged image the right manner round on the screen by inserting a biconvex lens in the aperture and placing a concave mirror in its focus. In illustration 5 (5 illustration), AB is the inverted image received in the focus of the mirror from the lens, and CD is the projected upright image. Porta describes his ‘Spectre and Magic Theatre’ in his 1589 published book on natural magic in which his “delighted, and often terrified audience, hardly knew whether what they saw was the true or only illusion. 11 Through the introduction of new technologies during the history of image projection, the audience has difficulty in establishing whether the image is real or illusory, and only once they became familiar with it – the apparatus becomes a commercial media object, thereby the magic is faded away.

The seventeenth century described as an age of social uncertainty and anxiety, that lead to a flourishing of illusionistic magic and stage plays, and influenced in the indirect ways the development of the invention of the magic lantern, which was developed by the Dutch scientist Christiaan Huygens in 1659. 12 (6 illustration)(6a illustration)Notwithstanding Koen Vermeir argues in his article “The magic of the magic lantern (1660–1700): on analogical demonstration and the visualization of the invisible”, that it is somewhat anachronistic to pinpoint a ‘true’ inventor, because looking from a present-day standpoint, ‘hybrids’ were created, combinations of camera obscura, lanterns, magic lanterns, solar microscopes, projection microscopes, projection mirrors and projection clocks; and making distinctions was not so easy. 13 The cubical shaped magic lantern was an optical box made out of different materials such as metal, wood or cardboard and projected images painted on a glass slide. Through the help of lenses that consisted of a plano-convex lens, with its flat side facing the light source, which converged the light rays onto the painted slide, followed at the end of the lens tube by one or two plano-convex lenses that enlarged the image and projected it the right way up. 14 (Mannoni, 2000) Inside of the box, an oil lamp with a silvered reflector was placed for concentrating the light beams towards the lens tube at the front of the lantern.

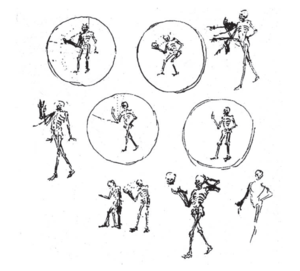

Huygens was not only occupied about the technological development of his apparatus but as well about the content of his pictures. On one of the manuscripts he drew images represent a skeleton, sometimes enclosed in a circle, removing its skull from its shoulders and replacing it, and also moving its right arm. In the penultimate illustration the skeleton, with its own head on its shoulders, is shown juggling a second head in the air. The sequence of images is quite remarkable because of its clearly indicated desire for artificial recreation of motion: dotted lines show the required movement of the skeleton’s arm. This is the earliest known representation of a moving slide for the magic lantern. 15 (Mannoni, 2000)(7 illustration) To be able to realize his early animation Huygens used two plates of glasses: on the first fixed one the skeleton was painted without its skull and its right arm, and on the second movable one the skull and the right arm was depicted. In contrary, the Dutch scientist never claimed the credit for making the first lantern device, because he had only seen it as an apparatus for superstition and entertainment.

Metaphysical Symbolism

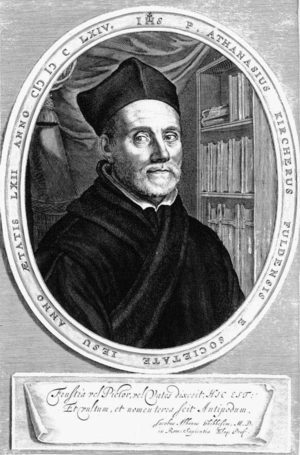

Next, to Huygens, it is important to underline the influence of the German Jesuit Athanasius Kircher,(8illustration) its self-reclaimed inventor of magic lantern. Already in the early stage of his carrier, Kircher became acquainted with the influential characteristics of light and operated his instruments to serve the power structures of the Catholic church in times of Counter-Reformation. The Jesuit was a true master of performing a balancing act between mysticism and theology, since he never denied the existence of monsters and demons, knowing that these were substantial for Catholic beliefs.

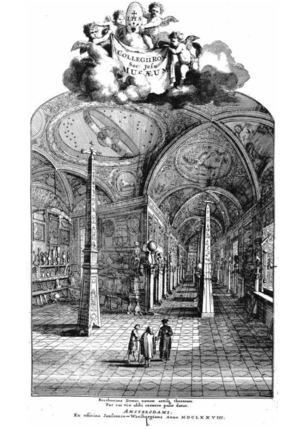

Stepping into Kircher’s universe it feels like, that we would enter his cabinet of curiosities museum in Rome (9 illustration), manifesting in his polymathic œuvre starting from his shadow-light studies till discoveries of harmonic compositions of sound. He was a fanatic collector of instruments and exotic objects, which influenced many of his “inventions” such as the metamorphosis machine(10illustration), inspired by Della Porta’s distorting mirrors. Kircher’s ‘catoptric transformations’ took place in a quite vast room. The guest who was taken into it would only see a mirror inclined towards him, high on the wall, lit from the front by the sun’s light entering through a window. As he approached, the visitor would see himself in the mirror, but on his shoulders would be the head of an animal. Eight different animal heads could be made to appear in succession. To do this, Kircher had constructed a large octagonal wheel, on the sides of which he painted eight different images representing the heads of animals resting on a human neck. The wheel was hidden in a casing, open only at its upper side, with a handle on the side to rotate the eight-faced wheel. Each image was reflected by the mirror, illuminated through the window of the room. The inclination of the mirror could be controlled by a cord. ‘It is certain that the head will appear sometimes as a cow, as a goat, as a bear, etc. All these will appear as though natural but on a human neck. 16 (Mannoni, 2000)

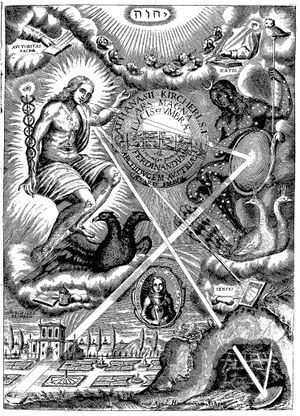

In 1644 he published his book Ars Magna Lucis et Umbrae, “The Great Art of Light and Shadow”, a true testament in pre-cinema history. (9a illustration) Here is it necessary to discover the connection between the texts and devices to be able to decipher Kircher’s metaphysical worldview – the hidden Neoplatonic structures of the universe, which demonstrated the visualization of the invisible. 17 As we have discovered at his metamorphoses machine his magic lantern could be interpreted as well metaphysically. If the original light source symbolizes God (lux) if the lens and the slide symbolizes an angel and man respectively, the image projected on the screen is furthest away from God, and properly depicts and symbolizes Death, demons and Hell. This might be a step too far, however, because of Kircher's Neoplatonism. In Christian theology, the demons are furthest away from God, but in Neoplatonic philosophy, there is no distinction between angels and devils, and all 'daemons' are superior spiritual beings located higher than a man in the scale of being. The proper place of demons is one of the thorny problems in every combination of Christianity and Neoplatonism. Kircher's metaphysics is flexible enough, however, and contains enough ambiguities to make it possible to fit in most natural and artificial objects. 18 (Vermeir, 2005)

If we compare the two magic lanterns designs of Kircher’s (6a illustration) and Huygen’s (6 illustration) we discover differentiations between the two. The design of the Jesuit does not enlarge as much the image than from the Dutch scientist. Different opinions are described in the academic circles around this phenomenon: Koen Vermeir is expressing that, in fact, Kircher was more interested in a projection process that did not enlarge the image, because he tried to transmit pictures over a long distance while keeping their size within limits. 19 Notwithstanding Siegfried Zielinski is stressing out, that Kircher places the transparent strips of glass with the images in front of the lens instead of between the light source and the lens; moreover, when two convex lenses are used, as he describes in the text, the projected images will be upside down. These errors are most likely the fault of the engravers 20 If we believe one or the other statement, the fact is that Kircher used the magic lantern himself for Jesuit theatrical productions and lectures. The dark room becomes a screening room, and the projection equipment is in a cubicle, invisible to the spectators. 21 (Zielinski, 2006)

Kircher’s student and editor Gaspar Schott described magic as 'whatever is marvelous and goes beyond the sense and comprehension of the common man'. 22 Only the educational gentry from higher social milieux was able to decipher the concealed memorandum and adore the performance. This lead to establishing an incisive higher class and the common man was prone to superstition. 23 Henceforth Koen Vermeir argues in his article “The magic of the magic lantern (1660–1700): on analogical demonstration and the visualization of the invisible”, that different kinds of 'illusion', however, refer not only to different social milieux; they are also conceptually distinct. The first - the delusion - presupposes that one surrenders to the image and loses oneself in the delusion. The second - the allusion - draws on a suspension of belief, a critical distance, a recognition of the joke as a joke. But often a joke is not just a joke, and one has the feeling of something really elusive, alluding to a deeper meaning. Only this third step really fulfills the possibilities of the rhetorical illusion. It is here that what I have called 'analogical demonstration' fits. This is not a demonstration in the sense of a mathematical proof, nor is it a direct experimental demonstration of a physical principle like the demonstrations of the anatomist, or the demonstration lecture. One can interpret it as a curious blend between the a-priori thought typical of rationalism and the experimental culture of empiricism. An analogical demonstration is a magical symbol visualizing invisible and hidden processes in nature. 24

I would like to conclude that from a metaphysical point of view Kircher's instrument would definitely function better than the other version of the magic lantern, because the experimental, metaphysical and theatrical demonstrations cannot be clearly separated. 25

List of references

1 The word hypernormalisation was coined by Alexei Yurchak, a professor of anthropology who was born in Leningrad and later went to teach in the United States. He introduced the word in his book Everything Was Forever, Until It Was No More: The Last Soviet Generation (2006), which describes paradoxes of life in the Soviet Union during the 1970s and 1980s. He says that everyone in the Soviet Union knew the system was failing, but no one could imagine an alternative to the status quo, and politicians and citizens alike were resigned to maintaining the pretense of a functioning society. Over time, this delusion became a self-fulfilling prophecy and the fakeness was accepted by everyone as real, an effect that Yurchak termed hypernormalisation. HyperNormalisation is a 2016 BBC documentary by British filmmaker Adam Curtis.

Wikipedia, accessed 6 December 2018, <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HyperNormalisation>

2 Merriam-Webster, accessed 6 December 2018, <https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/uncanny>.

3 Freud, Sigmund, ‘‘Das Unheimliche,’’ in Gesammelte Werke, vol. 12, ed. Anna Freud, Fischer, 1947

4 Grau, Oliver, "Media Art Histories", The MIT Press, 2010

5 Castle, Terry, "Phastasmagoria: Spectral Technology and the Metaphorics of Modern Reverie", The University of Chicago Press, 1988

5a Leeder, Murray, "The Modern Supernatural and the Beginnings of Cinema", Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2017

6 Hecht, Hermann, “The History of Projecting Phantoms, Ghosts and Apparitions”, Magic Lantern Society, 1984

7 Hecht, Hermann, “The History of Projecting Phantoms, Ghosts and Apparitions”, Magic Lantern Society, 1984

8 Ruffles, Tom, "Ghost Images: Cinema of the Afterlife", McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 2004

9 Ruffles, Tom, "Ghost Images: Cinema of the Afterlife", McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 2004

10 Hecht, Hermann, “The History of Projecting Phantoms, Ghosts and Apparitions”, Magic Lantern Society, 1984

11 Ruffles, Tom, "Ghost Images: Cinema of the Afterlife", McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 2004

12 Vermeir, Koen, "The magic of the magic lantern (1660–1700): on analogical demonstration and the visualisation of the invisible", The British Journal for the History of Science, 2005

13 Vermeir, Koen, "The magic of the magic lantern (1660–1700): on analogical demonstration and the visualisation of the invisible", The British Journal for the History of Science, 2005

14 Mannoni, Laurent, "The Great Art Of Light And Shadow - Archaeology of the Cinema", University Of Exeter Press, 2000

15 Mannoni, Laurent, "The Great Art Of Light And Shadow - Archaeology of the Cinema", University Of Exeter Press, 2000

16 Mannoni, Laurent, "The Great Art Of Light And Shadow - Archaeology of the Cinema", University Of Exeter Press, 2000

17 Vermeir, Koen, "The magic of the magic lantern (1660–1700): on analogical demonstration and the visualisation of the invisible", The British Journal for the History of Science, 2005

18 Vermeir, Koen, "The magic of the magic lantern (1660–1700): on analogical demonstration and the visualisation of the invisible", The British Journal for the History of Science, 2005

19 Vermeir, Koen, "The magic of the magic lantern (1660–1700): on analogical demonstration and the visualisation of the invisible", The British Journal for the History of Science, 2005

20 Zielinski, Siegfried, "Deep Time of the Media - Toward an Archaeology of Hearing and Seeing by Technical Means", MIT Press, 2006

21 Zielinski, Siegfried, "Deep Time of the Media - Toward an Archaeology of Hearing and Seeing by Technical Means", MIT Press, 2006

22 Vermeir, Koen, "The magic of the magic lantern (1660–1700): on analogical demonstration and the visualisation of the invisible", The British Journal for the History of Science, 2005

23 Vermeir, Koen, "The magic of the magic lantern (1660–1700): on analogical demonstration and the visualisation of the invisible", The British Journal for the History of Science, 2005

24 Vermeir, Koen, "The magic of the magic lantern (1660–1700): on analogical demonstration and the visualisation of the invisible", The British Journal for the History of Science, 2005

25 Vermeir, Koen, "The magic of the magic lantern (1660–1700): on analogical demonstration and the visualisation of the invisible", The British Journal for the History of Science, 2005