User:ZUZU/Thesis Process

A Soft Study of the Nearby

Introduction

The Disappearance of the Nearby: A Sense of Personal and Collective Loss

My research begins with feelings of disappointment, anger, and the impulse to escape—emotions that reached their peak during Shanghai's COVID lockdown, yet stemmed from deeper roots. Anthropologist Xiang Biao articulated an insightful concept when discussing globalization experiences—"the disappearance of the nearby." Nearby is not a given; it is a way of attending to the world a method to re-embed oneself in the fabric of social relations. He argues that "nearby" transcends mere proximity, representing instead a practice of negotiating self/other relations in hyper-globalized societies. This observation resonates profoundly with my personal experience.

As someone who frequently moves between different cities, I gradually discovered I had lost that immediate connection with specific places and specific others, replaced instead by a floating, rootless state of existence. This sense of loss reflects not merely my personal feelings but mirrors a broader social phenomenon.

In highly institutionalized urban spaces of contemporary life, our existence is functionally divided into work zones, leisure areas, and transit corridors, where we move according to invisible rules, rarely pausing to consider how these seemingly neutral urban structures subtly transform our relationship with our surroundings. When we become accustomed to passing through rather than deeply perceiving, those delicate connections that constitute "nearby" are quietly disappearing.

This is not merely a question of physical distance, but a transformation in our mode of existence where our capacity to form intimate connections with the surrounding world is gradually being lost. As French anthropologist Marc Augé observes, modern cities are saturated with "non-places"—those transitional, anonymous spaces such as airports, shopping malls, and subway stations that "cannot be defined as relational, historical, or concerned with identity" (Augé, 1995). Within these non-places, the relationship between people and space is reduced to functional, temporary connections, lacking the depth of interaction that nourishes meaning and belonging.

Rethinking the Nearby: A Methodological Exploration

In response to this "disappearance of nearby," my research attempts to pose a critical question: how might we rediscover and reconstruct "the nearby" within highly institutionalized urban environments? Exploring this question requires us to transcend traditional spatial understanding, viewing "nearby" not merely as geographical proximity, but as a sociological and emotional construction.

French cultural theorist Michel de Certeau offers an illuminating perspective in *The Practice of Everyday Life* focusing on how ordinary people reclaim and transform spaces predetermined by power structures through everyday "tactics." De Certeau suggests that tactics are the art of the weak, without a space of their own, operating in the territory of others, seizing opportunities as they arise, capturing possibilities in fleeting moments (de Certeau, 1984). This insight provokes me to consider: even within the most normalized urban spaces, might there still exist possibilities for reweaving the fabric of "nearby" through improvised practices?

This research conceptualizes "nearby" as a soft methodology, connecting memory, present practice, and future possibilities through temporal folds. This methodology does not pursue rigid definitions and classifications, but instead attends to those fluid, temporary, and elusive networks of relationships that constitute the core of everyday life. It permits us to search for fissures within seemingly solidified non-spaces, discovering those minute connections obscured by institutional logic.

Porous-Temporal Ethnography: Unveiling the Dynamic Generation of "Nearby"

To capture the complexity and fluidity of "nearby," I have combined several existing approaches, and this thesis adopts "porous-temporal ethnography" as its methodological framework. This framework allows us to transcend linear narratives by interweaving memory, observation, and future possibilities, thereby understanding "nearby" as not merely a spatial concept but also as a mode of temporal existence. As Lefebvre stated in *The Production of Space*, "Time and space are not separable within a texture so conceived: space implies time, and vice versa." (Lefebvre, 1991). Through this method, I attempt to capture the subtle connections and fleeting possibilities that conventional research approaches often overlook, examining "nearby" through four interwoven temporal layers:

1. The Distant Past: exploring my personal experience of losing "nearby" and how this loss has triggered a reflection on its importance, situating my narrative within a broader socio-cultural context through autoethnography

2. The Closer Past:analyzing the relationship between nearby and my artistic projects from the previous year, particularly those experiments that sought to reconstruct intimate connections with the surrounding environment through creative practice

3. The Continuous Present:observing micro-practices and encounters with the ‘ nearby’ in everyday life.

4. The Possible Future:I will reflect on the resistance potential of the ‘’ nearby‘’ as an unfinished project.

Each chapter concludes with "Annotations from Now" – my re-inspection of the record of the past, an attempt to interweave different layers of time.

Through this thesis, I aim not only to contribute to theoretical discussions of urban space, but also to offer a new way of sensing and experiencing the nearby—one that is more attentive, more focused on subtle and small-scale relationships. In the highly mobile and institutionalized modern city, “nearby” may no longer be taken for granted, but it can still be rewoven through careful observation and improvisational practice, as a form of active exploration into new types of relationships. This thesis stitches together field notes, urban ethnography, and fragmented workshop documentation to create a living archive of the nearby—not a fixed geography, but something derived from it. Through my lens as an embedded participant, I engage with the nearby using deliberate, detailed observation and temporary tactics to counteract social fragmentation.

The nearby as a scope of seeing is fluid and generative. It is fluid because its internal relations are constantly changing; it is generative because it enables us to see and do new things. The nearby is, thus, very different from ‘community’ that is based on stable membership and homogeneity.--The Nearby: A Scope of Seeing by Biao Xiang |

Chapter 1 The disappearance of my nearby and the urgency of reshaping it

Having lived in Shanghai for nearly three decades, this city forged from steel and velocity has taught me a contradictory law of survival: We jostle shoulder to shoulder yet remain blind to each other's existence. Daily sharing elevators and subway cars with hundreds, yet never retaining the shape of any pair of eyes. The distance between people appears minimal, yet emotional connections remain cavernously hollow.

When newcomers ask "Where are you from?" my tongue feels weighted down by an iron lump – physically speaking, a hometown should be the place that most shaped my growth, yet I struggle to designate any concrete location. In this steel labyrinth, I've followed hyper-socialized tracks – born, schooled, employed, life becoming a relentless race with no finish line. I'm like a glass marble launched into motion within a clearly bounded game box, ricocheting off the bumpers of societal machinery. Even accompanied by pulsating music and strobe lights, the trajectory inevitably ends in a dark vortex not far from the starting point. When I am forced to answer this question, it feels like conceding to the idea that I truly come from a game box.

During the COVID-19 lockdowns in Shanghai, this phenomenon became particularly stark. In a residential building where I lived for over three years, I encountered neighbors daily but never established meaningful connections. Our interactions, or lack thereof, reflected a broader urban trend: individuals existing side by side without forming genuine ties.

One vivid moment from that time stands out. I took a photograph of an elderly neighbour waiting for the lift, attracted by her outfit - a unique mix of quirky patterns that I found endearing. Although we lived in the same building, I didn't know her name or her story. Like many city dwellers, my neighbours and I shared a mutual indifference: during the lockdown, our building became a microcosm of imposed proximity. We were confined to the building for two months, unable to leave except for mandatory COVID-19 tests at unpredictable times - sometimes at 5am, sometimes close to midnight. The lifts, crammed with ten or more residents during these tests, became a surreal space of both enforced closeness and profound isolation.

When I reflect on this period of daily life, I realize I have almost no photos taken in the building where I lived for three years, let alone pictures of the elevator. The only one I took was because I found an elderly person’s pajamas pattern very interesting. My scattered collection of documentary photos often includes elderly people wearing outfits with peculiar designs. I took these pictures but never thought about making any connection with them. Perhaps it’s due to a societal convention in certain environments that approaching strangers will make you seem like a scammer. And I didn’t want to be seen as one. |

As time went on, I began to feel suffocated. The rules were arbitrary and often absurd, but no one questioned them. Eventually, I couldn't help myself. I posted a message to the group outlining several logically flawed policies and asking for clarification from the administrators. What struck me was the response - or lack of it. Out of some 300 participants, not a single person engaged with my message. It was ignored, quickly buried under updates about group food purchases and other day-to-day concerns.

Later, when I challenged the policy a second time, a neighbour finally approached me - not to discuss my points, but to accuse me of being a foreign spy sent to undermine the government. This was the first "conversation" I had had with a neighbour in my three years there, though "conversation" might be too generous a term. It was an exchange, but one rooted in suspicion and absurdity.

I developed a strong urge to run away, and it wasn't the city itself that I fled from, but a deeper sense of collective disillusionment - disappointment in those around me, which included disappointment in myself, and I was also an accomplice in constituting my nearby - how could I blame the apathetic masses if I never attempted to make a connection?

A common criticism on the Chinese internet is that people "don't care about specific individuals," becoming collectively obsessed with grand narratives. They focus more on grand stories, like the nation or collective suffering. These narratives often ignore how people live each day. Philosopher Jean-François Lyotard once described how, in the postmodern era, grand narratives lose their meaning. They can’t fully speak for the complexity of everyday life. During the lockdown, these big stories became more powerful. Policies were made for “the people” or “public health,” but they often silenced personal voices.

Michel Foucault described this kind of system as biopolitical—it manages people not just with laws but through control of bodies and space. Naomi Klein, in her book on disaster capitalism, said that crises often become tools to expand control. Under lockdown, we were told to isolate, to follow, to keep quiet. The closeness between people disappeared. Neighbors stopped greeting each other. Technology helped track movements. Rules replaced conversation. What we lost was not just freedom. We lost “nearby.”

The erosion or weakening of close, everyday social interactions and the ability to take concrete, meaningful actions in the immediate, everyday context. This "disappearance of nearby" phenomenon represents not merely a change in spatial or physical relationships but a transformation in ways of being. Martin Heidegger believed that human existence is shaped by our being in the world. When this world becomes divided and monitored, that basic way of being is also disrupted. Still, not all resistance needs to be loud.

American political scientist James C. Scott (1990),in his book Weapons of the Weak describes how marginalized groups maintain dignity and autonomy through subtle resistance behind surface compliance. These "hidden transcripts"—discourses and actions that cannot be openly expressed but are privately shared—constitute a form of "infrapolitics" that erodes the foundation of power without directly challenging it.

For marginalized actors, who often lack representation in grand narratives and broad policy discussions, focusing on their day-to-day realities can highlight their specific needs, struggles, and strengths. However, in this environment of systemic alienation, how can ordinary people engage in small yet significant acts of resistance in everyday life? De Certeau (1984) proposed the concept of "politics of everyday practices," suggesting that ordinary people can reclaim and transform spaces dominated by power structures through seemingly insignificant daily actions.

This "politics of nearby" is not naive utopian resistance but acknowledges that in highly monitored and regulated social environments, the act of establishing genuine connections itself carries profound political significance. Feminist theorist Donna Haraway (1988), in her essay on situated knowledge, reminds us that resistance need not always take the form of grand social movements but can be embodied in valuing and cultivating minute connections in everyday life.

Chapter 2 Fine-Tuning the Everyday: Artistic Interventions in Nearby

This chapter reviews two art projects—from protocols for active archives to the urban loitering experiments—and I noticed a recurring pattern among these seemingly different themes. Each study uniquely returns to the core question: how do individuals form connections with their surroundings?

What first appeared as coincidental overlaps gradually emerged as a consistent methodological thread. These projects serve as experiments in reconstructing proximity through tactile, sonic, and spatial interventions. I analyze the gift economy of the Rain Receiver and the Emohoohoo, tracing how each work stages different modes of relational negotiation.

Touch and Giving Back

In Radio Worm: Protocols for an Active Archive, I developed this project in a group collaboration. For the final post-apocalyptic theme, we imagined the audience as survivors of the apocalypse. Through the Rain Receiver, we analyzed the language of nature by capturing the frequency of rain to generate sounds.

When survivors touch the Rain Receiver, they become part of an unfolding narrative. This intimate gesture, akin to the act of giving, triggers a cascade of experiences—rain sounds, fragments of stories, and stream-of-consciousness memories collected from the community.

The concept of a gift economy(Kimmerer, 2022) became central to our exploration. For example, while a person can buy a wool scarf in a store, receiving a scarf hand-knitted by someone close carries a different emotional weight. Both serve the same physical function of keeping someone warm, but the emotional connection to a gifted item is far deeper. This realization resonated with my preference for the metaphor of a post-apocalypse picnic box. In a gift economy, community networks are built not on material wealth, but on connections that avoid disrupting the natural flow of resources for artificial scarcity.

As Ife, the creator of Third Space, mentioned in a previous interview, she gained a sense of belonging at WORM (an art space based in Rotterdam). This belonging carries a gift-like quality that naturally fosters gratitude, which in turn encourages positive reciprocity.the act of giving—whether sound, wool, or space—created circuits of mutual recognition that no apocalyptic scenario could fully erase.

This suggests that even in imagined futures of scarcity, the deepest resource we have is the protocols we devise for being together: the true connection is built not through ownership, but through shared moments of presence and care.

Loitering and Emohoohoo

While working on this project, I started thinking about why I enjoy walking without purpose. I realized there are many reasons. One of them might be that it’s a late rebellion against my childhood, when I wasn’t allowed to play freely. I was told to be a “good kid,” go straight home after school, and finish my homework. Running around outside was seen as something only “wild kids” did. When I became an adult, I finally had my own time, but society trained me to be a cold, rule-abiding city person. I quickly, and without realizing it, accepted these rules: staying quiet and behaving in public spaces.

I’ve taken many photos while loitering. They capture moments of absurdity or fun in daily life,I realized I enjoy doing nothing. But as adults, it’s easy to lose the ability to laugh freely or express emotions openly. One memory stands out: during a winter trip, my mom and I visited a frozen river, a famous seasonal attraction. I’ve never seen her so happy. She skated on the ice like a child, screaming with joy. That environment made such emotions feel acceptable. But in cities, adults are only allowed to show emotions in specific, paid-for spaces, like theme parks or cinemas.

In the context of How to Do Nothing: Resisting The Attention Economy (Odell, 2019),the author discusses how contemporary society's emphasis on efficiency, productivity, and digital media's fast pace continually disperses and manipulates people's attention. Odell proposes the idea of "doing nothing" as a means to counteract this attention economy, which is characterized by the ubiquitous spectacles of attention-seeking in urban environments, as described in "Society of the Spectacle" by Guy-Ernest Debord. These spectacles incessantly attract attention and contribute to feelings of exhaustion and disillusionment with the surrounding environment.

In The Metropolis and Mental Life(Simmel, 1903/1961), Georg Simmel described how highly urbanized environments bombard us with countless visual, auditory, and activity-based stimuli. This leads to sensory overload and a resulting numbness. People become less emotionally responsive to events and experiences that would normally provoke reactions.

Based on these reflections, I designed a sofa installation that expands and contracts in response to emotional fluctuations. This work tries to explore emotional freedom, a form of freedom that deserves attention but is often overlooked. It raises a key question: under the dual pressure of urban discipline and the attention economy, how can we regain the ability to genuinely engage with our surroundings and our own emotions?

When the ‘Emohoohoo’ sofa is at rest, it is merely a shrivelled, transparent plastic body, sprawled helplessly on the floor. At the exhibition site, I placed a power bank and other electronic components in a comical McDonald's fast food box. This visual choice echoes the logic of the entire installation: the grotesque in the mundane, the juxtaposition of consumer culture and emotional expression.

The most fascinating part was the interaction between the participants and the installation. When I explained how the sensor captured emotional fluctuations, a subtle sense of self-awareness immediately spread through the space. People instinctively tried to control their emotional states—some failed to stay calm, while others succeeded in maintaining controlled emotional shifts through self-monitoring. With the emotional efforts of around seven or eight participants, the limp plastic shell gradually inflated and eventually transformed into a temporary space for rest.

This work is part of my attempt to rebuild an intimate connection with my surroundings. It placed emotional expression and physical presence into an absurd but tender structure. In the context of city life, where subtle emotions are often suppressed.This sofa gives people a space to respond to their own feelings. Modifying the function of everyday objects can lead participants to observe the neglected movements and micro-practices of daily life, and to reexamine the everyday relationships that we often take for granted.

Specially designed for adults prone to embarrassment. EmoHooHoo supports the outward expression of unspoken emotions in public places; once you wear this device, it clumsily reflects your emotional changes, whether you like it or not 💨💨💨 In urban life, emotional expression is confined to specific occasions, often requiring an entry fee. To achieve emotional freedom in a consumer society, we must first dissolve this embarrassment. EmoHooHoo helps you break free from societal constraints. If burdened, attribute responsibility to our device💨💨💨 |

While walking in Rotterdam and engaging in activities like observation lists and coded walking, I find unconventional behavioral patterns intriguing. I am exploring my connection with this city by deviating from traditional map representations, discovering how unconventional walking can forge connections within typical routes (such as from home to school or home to the market). |

Chapter 3 Touch, Draw, Act: Experiments in the Nearby

In this chapter, I will document a series of experimental workshops that explore the concept of “nearby.” These workshops began with fleeting yet subtle moments in my daily life. Later, they expanded into collective explorations of collective consciousness.

The Nearby is the core of my ongoing research. It is the complex entanglement of relationships and behaviors shaped within specific scope of seeing.It reveals tensions between the body and environment, between individuals and collectives, between reality and imagination.Space transcends neutral containers. It is shaped by social relations and also shapes them. In a modern city where life is highly functional and fragmented, how can we rethink and reimagine this entanglement? How can we recover possibilities of connecting with space and with others?

These workshops are my attempts to explore these questions. They challenge the taken-for-granted behavior patterns described by Michel de Certeau in his writings on everyday practices(De Certeau, 1984). Through collective bodily perception, participants created temporary communities. In these communities, they co-created spaces that exist both within and beyond everyday life. These actions interrupted ordinary time and order. They became a way to explore and define what "nearby" and "connection" mean.

The elevator project

The objective is to develop small-scale projects that shift the focus to the mini-moments of everyday life. This project focuses on the elevator, a space that was identified as a crucial hyperspace medium in my previously life experience. The existence of such a space within the context of daily life is a subject of considerable interest to me. In these confined spaces, individuals frequently share a common destination, whether it be a residence or workplace within the same building. However, despite this physical proximity, their interactions often give way to awkwardness and silence. It is noteworthy that this particular form of social awkwardness only became apparent to me after my arrival in the Netherlands

When I first moved to the Netherlands to study English in a northern student city Leeuwarden, I lived in a typical student dormitory. It was there, for the first time in my life, that I began interacting with strangers in elevators—though passively. I vividly remember one encounter. A young person, deeply focused on her phone, quickly murmured something like, "I’ll be done in a moment," as the doors opened. A few seconds later, she slipped her phone into her pocket and naturally started a conversation with me. While I no longer recall what we discussed, I distinctly remember being impressed by how effortlessly she shifted her attention from her phone to engaging with a stranger. This seemed like a personal gift of hers, the ability to turn an awkward moment into a genuine connection.

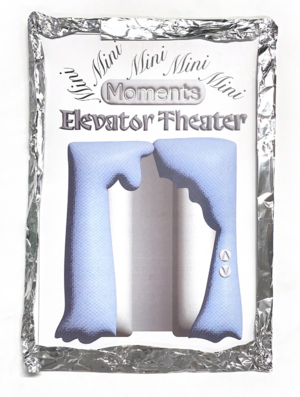

Mini Moment: Elevator Theater is an interactive exploration of how we inhabit shared spaces and express ourselves through body language and behavior. This project invites participants to reflect on their own experiences in the elevator, a small but intimate environment that often brings out different aspects of our personalities. |

Inspired by this memory, I chose elevators as the site for exploring connections between space and proximity. For the Public Moment , I created a small role-playing experiment. Each person entering the elevator was assigned a character to interpret and embody freely. This experiment drew from Erving Goffman’s _The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life_, where he argues that people consciously perform varying versions of the self in different everyday spaces. I was curious whether such performances could transform the atmosphere of a closed space like an elevator or influence people’s physical behavior within it.

As an extension of this project, I began developing a personal Self-Protocol plan. I called it the Elevator Sunflower Protocol, imagining myself as a sunflower—bright, open, and welcoming. Over time, however, I noticed something unsettling: I felt less like myself and more like an actor performing a role. In elevators with others, I experienced pressure to “deliver” the protocol as if on stage. When alone, I felt a strange relief, as if retreating behind a closed curtain. This performative nature made me question the authenticity of my experiment. Was I truly fostering connection, or merely acting out an idea?

the Elevator Sunflower Protocol diary As I stepped out to lock my door, another door at the end of the hallway opened. I remember this room once housed a cat-loving tenant who moved out last week. This time, a new tenant emerged—a stern-looking person with a red hiking stick. We entered the elevator together, but the person quickly turned to face the door, avoiding any interaction. I missed the chance to smile and greet ta. When the elevator doors opened, ta rushed out toward the subway station. It was raining outside as I returned from the supermarket, and at the front door a person in front of me was carrying two heavy shopping bags and struggling to find the keys. I offered to open the door and, of course, we got into the lift together. I realised that I had seen this person before - once with immaculate make-up. The person smiled shyly and jokingly said, "My bag is always badly organised. |

I realized I needed to invite others into the process to bridge this gap, transforming it into a collective experiment. Inspired by Edward T. Hall’s The Hidden Dimension, I wanted to explore how the immediate surroundings—both physical and social—shape interactions. I considered designing simple invitation cards to explain the project and include a link to a digital space, an "elevator diary network," where participants could record and share their experiences. These cards could circulate beyond my control, transforming elevators everywhere into nodes of connection.

Elevators, often characterized by rigid unspoken rules, could become experimental sites for small acts of defiance—redefining proximity, reimagining social scripts, and fostering hidden yet interconnected communities. As an experimental space to explore how bodily actions and spatial contexts might disrupt social norms and open pathways for subtle resistance.

Nearby Nail Salon

Collective Nearby View

I hosted a workshop aimed at exploring how people perceive their nearby surroundings and their own daily imagination. The goal was to combine personal experience with collective action. The workshop unfolded in three stages: constructing an imaginary self, collaboratively creating a surreal "Nearby," and embarking on an outdoor adventure to explore the physical world.

This exploration was inspired by a moment during my walk from school to the Leuvehaven port. I encountered a bird standing high on a metal pole, facing the wind as the air currents ruffled its feathers. I could hear the subtle sound resonating from its belly. For a brief moment, I felt as if I was that bird or people in my nearby are be represented by this bird— or perhaps, the bird embodied the life I imagined for myself. Living here, I often experience a strange sense of ease, which I recently realized stems partly from my inability to understand European languages. As I wander through wide and narrow alleys, the movement of sound waves and the fluttering of my clothes surround me. Yet, I am shielded from passive information. Like the bird, I am surrounded by towering cranes, buildings, and shimmering water. The bird simply stood there, its tiny eyes gazing into the distance or the void. After a while, it flapped its wings and flew to the ground nearby.

This reminded me of a recent trend on the Chinese internet, where people humorously diagnose themselves as different objects. For instance, someone identifies as an egg tart — with a crunchy body and a rounded shape, that feel like the whole thing is going to break under the slightest pressure. Others see themselves as toast — jumping up when the morning bell rings. People's daily identities are deconstructed into witty metaphors. Inspired by this, I designed a workshop where participants could explore their imagined daily lives and experience others' "Nearby" in a playful, relay-like process.

The Workshop Structure

Create Your Imaginary Self (10 min):You can be an image made up of various materials, such as a goldfish made of bread, a block of ice, or a woolen doll with teeth and claws.

Create a Collaborative Nearby (15 min): Each participant contributes to a shared landscape by drawing on a large sheet of paper divided into three sections:

First person: Draw the upper layer — what is above the line of sight, such as the sky, ceiling, or blurry treetops. Fold the paper, leaving some hints for the next person.

Second person: Create the middle layer — such as traffic lights, people, objects, etc. Fold the paper again.

Third person: Draw the ground — such as corners, trash bins, pavements, cracks, creatures, and passersby's shoes.

Outdoor Adventure (25 min): Take the Collaborative Nearby, your imaginary self, and explore the actual surroundings. Look for the elements from your drawing, take photos, or record your interaction with these elements and your feelings.

I collected the drawings afterward, and their presentation surprised me. The feedback session will be conducted later after gathering participants' reflections and experiences for further analysis.

Chapter 4

Back to the past

In early 2025, I returned to China for Chinese New Year. It was a strange change of perspective, as if it had been moved slightly and put back again, but all the angles had shifted. I found myself in an automatic fit with the city: each space had its definite function, and my actions fit seamlessly into those functions. In a very short period of time, I was immediately integrated into this grey metropolis. However, beyond this highly functional fit, I became aware of another, more implicit spatial system - that of the neglected, temporarily occupied, but vibrant ‘’leftover space‘’.

Urban Leftover Spaces refer to the unplanned, overlooked, or marginal spaces in the city—corners of parks, alleys, spaces beneath bridges—that remain outside the formal urban grid yet become sites of spontaneous social activity. These spaces are not passive backdrops but active components of urban life.

In this city there is a strange pull between people. Strangers don't look at each other, they don't smile, but they are loose in their own ‘nearby’.This looseness is not relaxation in the traditional sense, but a kind of casualness, an occupation of space without thinking.

I saw a woman in the park using a tree trunk for exercise. She was rubbing her legs back and forth on the tree, occasionally hitting the trunk with her back. I was sitting on a bench next to her, and in the distance in one direction someone was playing an erhu, in another direction someone was playing a saxophone, and I couldn't see the players, just the voices. Nobody finds this strange. In Shanghai's parks, scenes like this are so commonplace, so ordinary, that they feel part of the air, creating a pattern of behaviour that is not explicitly defined but collectively accepted. These subtle modes of interaction make Urban Leftover Spaces an important part of everyday urban life.

In the alleyways left behind in the urban villages, I see Adhocism being practised in the most direct way: everything solid can be a support for drying clothes. Clothes are put on tiles and hung on the pipes of air-conditioning units, as if they were randomly thrown up by the wind. Objects that traditionally belong to the private sphere are generously displayed in these public spaces, breaking down the boundaries between public and private in urban space.

These acts are not merely pragmatic but political. They reclaim agency within a system that prioritizes efficiency over intimacy. Henri Lefebvre’s “right to the city” manifests here as a quiet rebellion: the right to misuse space, to bend its intended function toward human need.

This kind of Adhocism of space occupation is not only a reuse of resources, but also a construction of a sense of belonging. When I stood at the intersection of the alleyway to take a picture, I suddenly hesitated a bit, and I realised that I looked like an untimely intruder. Their nearby is composed in this way, temporary, broken, casually occupied, yet with a certain subtle order. These occupants greet each other skilfully, adapting themselves to their environment in such a way as to make the alley a fluid but solid community. And in these remaining spaces, people are not just adapting to the urban environment, they are also actively shaping it to make it more relevant to their own needs.

Richard Sennett’s notion of cooperation as a “skill to be learned” . Adhocism is not chaos but a form of tacit collaboration. The alleyway laundry lines, for instance, operate under an unspoken code: clothes are hung but never stolen; space is shared but never monopolized. Similarly, the park’s cacophony of erhu and saxophone coexists without formal coordination. These interactions embody what Sennett calls the “rituals of cooperation”—small, repeated acts that build trust in a fragmented world.

Yet this cooperation is fragile. When I hesitated to photograph the alleyway, I felt the weight of my outsider status. To the residents, my camera threatened to expose their improvised order to the scrutiny of formal systems. Their “nearby” was a delicate ecosystem, sustained by collective complicity in bending rules. This mirrors the lockdown experience: just as questioning authority in the group chat led to accusations of subversion, documenting the alley risked rupturing its fragile equilibrium.

The fragility of cooperation, characterised by a state of exposure and erasure, elucidates the precarious symbiosis between informal systems, whether social or spatial, and formal power.

The tension between systemic control and spontaneous agency, as explored in the context of Shanghai's lockdowns, finds its spatial counterpart in the concept of Urban Leftover Spaces. These interstitial zones – alleys, underpasses, neglected park corners – defy the rigid functionality of modern urban planning, representing cracks in the city's armour where informal life flourishes. In these spaces, the concept of "nearby" is not eradicated but rather reimagined through ad hoc practices, which serve as modes of survival and creativity that thrive in the ambiguity of these environments.

The banners of urban policy may declare grand visions, but life unfolds in the cracks. These acts invert the hierarchy of urban design: rather than spaces dictating use, use defines space.This inversion echoes the tension between grand narratives and marginalized realities explored in Chapter 1. Marginalized groups—migrant workers, elderly residents, street performers—are often excluded from formal urban narratives. Yet in leftover spaces, they enact what Charles Jencks termed adhocism: “making-do” with what is at hand. Their improvisations are not merely survival tactics but assertions of belonging.

Adhocism as Privilege

While these acts echoed Shanghai’s improvisations, their stakes diverged sharply. In Rotterdam, my adhocism was recreational, even whimsical—a choice rather than a survival tactic. The city’s tolerance for such play felt like a luxury, a product of its welfare-state safety nets and participatory planning traditions.

This contrast underscores the duality of leftover spaces. In Shanghai, they are sites of urgency—responses to systemic neglect, and authoritarian governance. In Rotterdam, they are sites of leisure—experiments enabled by relative security. Yet both cities reveal adhocism’s universal power: its ability to transform sterile environments into sites of connection. As Jane Jacobs observed in The Death and Life of Great American Cities (1961), vibrant urban life depends not on grand designs but on “the ballet of the sidewalk”—the unplanned interactions that arise when people feel free to appropriate space.

The disappearance of the nearby is not inevitable. In leftover spaces, the nearby is not a static proximity but a dynamic practice—a verb rather than a noun. These acts, though fleeting, stitch together a fabric of connection that resists the alienation of both hyper-urbanization and over-policed collectivism.It is where the self, through adhocist acts, reaches outward, not toward abstraction but toward the stranger on the bench, the neighbor in the alley. In this way, the nearby becomes a bridge: between control and freedom, indifference and cooperation, disappearance and reclamation.

Adhocism is neither inherently liberatory nor inherently exploitative. In Shanghai, it is a lifeline for those excluded from formal systems; in Rotterdam, it risks becoming a bourgeois aesthetic—a “staged authenticity” (MacCannell, 1973) that romanticizes poverty. Yet both contexts affirm that the nearby cannot be engineered through policy alone. It must be practiced.

To return to Xiangbiao’s framework: if the “very near” (self) and “very far” (nation) dominate modern consciousness, leftover spaces offer a middle ground—a scale of the body where strangers become collaborators in rewriting urban life. Here, the nearby is neither swallowed by the self nor dissolved into abstraction. It is, instead, a verb: an ongoing negotiation between control and creativity, survival and play.

References

ReferencesAugé, M. (1995). Non-places : Introduction to an Antropology of Supermodernity (J. Howe, Trans.). Verso.AugéM. (2008). In the metro. Minneapolis Univ. Of Minnesota Press.De Certeau, M. (1984). The Practice of Everyday Life (S. Rendall, Trans.). University of California Press.Debord, G. (1977). Society of the spectacle. Black & Red.Foucault, M. (2008). The Birth of Biopolitics Lectures at the College De France, 1978-1979. Palgrave Macmillan.Goffman, E. (1959). The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. Doubleday. https://monoskop.org/images/1/19/Goffman_Erving_The_Presentation_of_Self_in_Everyday_Life.pdfHall, E. T. (1990). The hidden dimension. Anchor Books.Heidegger, M. (1962). Being and Time (J. Macquarrie & E. Robinson, Trans.). Blackwell. (Original work published 1927)Jencks, C., & Silver, N. (1972). Adhocism : the case for improvisation. Secker And Warburg.Kimmerer, R. (2022, October 26). The Serviceberry: An Economy of Abundance – Robin Wall Kimmerer. Emergence Magazine. https://emergencemagazine.org/essay/the-serviceberry/Klein, N. (2007). The Shock doctrine: the Rise of Disaster Capitalism. Vintage Canada.Lefebvre, H. (1991). The production of space (D. Nicholson-Smith, Trans.). Blackwell.Odell, J. (2019). How to do nothing: Resisting the attention economy. Melville House.Simmel, G. (1961). The Metropolis and Mental Life. Chicago, Syllabus Division, University Of Chicago Press. (Original work published 1903)Sommer, R. (1969). Personal Space The Behavioral Basis of Design . Prentice-Hall,Inc.Whyte, W. H. (1980). The social life of small urban spaces. Project For Public Spaces.Xiang, B. (2021). The nearby: A scope of seeing. Journal of Contemporary Chinese Art, 8(2), 147–165. https://doi.org/10.1386/jcca_00042_1