User:ThomasW/save and forget

Save & Forget

Thomas Walskaar MDCGRS04_Graduate Research Seminar_2014-2015 The Piet Zwart Institute

Introduction

“It matters because we live in media, as fish live in water.” - Ted Nelson (Wardrip-Fruin, 2003, p306) As a society we always seem to be looking for a new technical solution for knowledge and information storage. We hope there is one magic, final solution that will solve every issue, but easy solutions create their own problems. The perceived view of the stable nature of digital information differs from reality. Problems like obsolete physical formats, lost or non functional machines, companies that go bankrupt, file formats with no support in the future, and changing user licenses are some of the many points of failure. It seems the more technical the technology gets, the more problems it creates, as researcher Jennifer Gabrys writes in Digital Rubbish: A Natural History of Electronics:

“Much of the technology in the museum or archive of electronic history is inaccessible, however: ancient computers do not function, software manuals are unreadable to all but a few, spools of punch tape separate from decoding devices, keyboards and printers and peripherals have no point of attachment, and training films cannot be viewed. Artefacts meant to connect to systems now exist as hollow forms covered with dust. In this sense, the electronic archive can be seen as a “museum of failure.” (Gabrys, 2007, p64)

This thesis will explore the questions, if there is any such thing as a perfect storage technology and how we relate to information as individuals when they are located on storage devices. This thesis is the result of broad research done over two years into the topic of memory storage at The Piet Zwart Institute in Rotterdam, a topic I started while working on during my Bachelor.

I have written this thesis in a way that makes it easier for people less familiar with the subject to understand the topic. Although there are many academic texts on the discourse of archives and memory in media theory today, I want to focus on the “individual” rather than the larger institutional aspects of this topic. In the first chapter “Ink, Photography and Bytes” I will explain the history of storage mediums, from The Library of Alexandria to the invention of microfilm to today’s digital storage mediums and how there has always have been a promise of the “better solution”. In the second chapter “The Cloudy Commercial Complex” I will look at what the «cloud» is and its effect on how we store our information and what risks we are taking by relying on a third party. In the last chapter ”My Hard-Drive Died Along With My Heart” I will look at how people deal with the loss of information after their devices fail.

Chapter One

Ink, Film and Bytes

“The media of the present influence how we think about the media of the past or, for that matter, those of the future.” (Kittler, 1999, pxxi)

Library of Alexandria

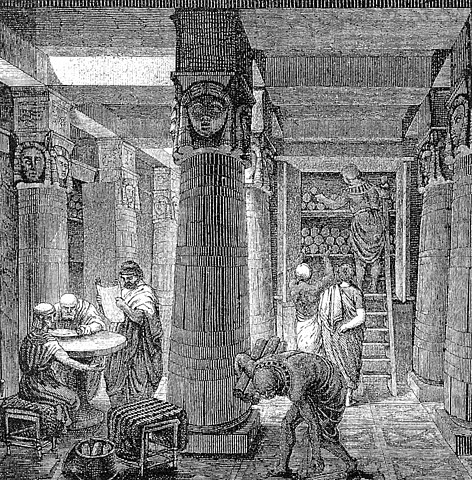

One of the first, and best-known, repositories of knowledge in ancient times was the Library of Alexandria. It was the first collection of books and texts from more than one country and consisted of mostly Egyptian, Greek and Roman texts. The growth of the collection can be attributed to local law that stated that all new arrivals had to hand over their written texts so they could be copied. “It was as much a political decisions as it was an ideal of knowledge sharing” Fernando Beaz writes in The History of the Destruction of Books, which describes the link between government and its libraries: “We have to remember that museums and libraries were closely linked to the nation’s power structure, so when they were burned to the ground, silence legitimized the catastrophe.” (Baez, 2008, p2) The collection in Alexandria was not concentrated in one central location, but was distributed between different warehouses all around the city, most of which where at the docks in Alexandria, close to the ships from which the collection came from. “There was a huge investment in labour, and a whole system was in place to feed skilled labour to the library and its infrastructure and upkeep. “The copying and classification of texts was the labor of entire generations educated according to the methodical axiom of the peripatetic school” (Baez, 2008, p46)

The Library of Alexandria in a illustration from the 19th century. (O, 19th century, Online)

The Library of Alexandria in a illustration from the 19th century. (O, 19th century, Online)

As the library was a part of a larger power structure, it was naturally a target for those opposed to the current political system. Contrary to popular belief, it did not burn down once. Its destruction happened over time, from around the year 145 BC to its last big conflagration in 642 AD. The suspected culprits of these burnings where many, and still unknown to this day, but the main culprits accused have included everyone from the Romans, Christian rebels opposing the ruling Egyptian powers, earthquakes and economical collapse. As it was part of the state system, different ruling powers may have had different opinions on the importance of the library. The main format for recording texts in ancient Egypt was papyrus, it was cheaper to record on papyrus then clay tables, even through the papyrus was less durable. Baez points out: “Nowadays there are no examples of Greek papyri prior to the fourth century BCE. In fact, despite the labor of libraries and the widespread book business of the Hellenistic era, texts on papyrus not recopied or copied onto codisc, were lost.” (Baez, 2008, p88)

The fact is that it was cheaper to make, made papyrus the dominate format of recording, the quality or durability was not the main concern of the user at that time. This made it, as Beaz writes, a real concern from the monks in the ancient times: “paper was introduced during the ninth or tenth centuries, and the first paper found there is of the oriental type (called bombykinon or bambakeron). The fact that is was cheaper than other material gradually gave it ascendancy, but its rapid deterioration was a matter of great concern to the monks.” (Baez, 2008, p95)

Not much changed for the medium of paper before Johannes Gutenberg, in 1439, introduced mechanical movable type printing. No longer were books and the print words for the few. Later the invention of the mediums of photography and sound recording in 1800s changed the way information was generated and stored. The medium photography would later allow the development of microfilm.

Microfilm

John B. Dancer invented microfilm in 1839, which, compared to a collection of printed books, proved to be a space saving endeavour, but the main use of microfilm as an archive medium was not fully grasped before Paul Otlet started using it for his library. Paul Otlet, was a 19th century utopian, an inventor, peace activist and Internationalist with a firm belief in building a new world based in pacifism and progressive ideals through spreading universal knowledge. This was a response to the political landscape of his day, with rising nationalism throughout Europe.

He invented the universal decimal classification system for libraries, together with lawyer and president of the International Peace Bureau Henri La Fotaine. By using this system he wanted to advance human progress through sharing information. The system was made from paper index cards, colour-coded and filed in custom-made drawers. Otlet was thinking how in the future it would be possible to combine different mediums, he predicted: “Phonographs, radio, television, telephone — these instruments taken as substitutes for the book will in fact become the new book, the most powerful work for the diffusion of human thoughts. This will be the radiated library, and the televised book.” (Truefilms, 2007, Online)

After Otlet, more people and companies started using microfilm as an easy way of storing and spreading information, often with the idea that the paper archive was turning into dust and need to be migrated over to the new format of microfilm. The notion of paper archive turning into dust and was obsolete was one of the stories being retold and it was urgent to move them over to microfilm, the notion was that microfilm would preserve the content better than paper, as there was a notion that paper archives where turing into dust. The process involved was itself destructive, as the book was cut open by removing the spine in order to be photographed. The truth is that it was mostly a marketing tactic from the manufactured and sellers of microfilm. The truth is that paper archives were not turning to dust, and the destruction was the process of putting the paper originals on microfilm. As Silverman points out: “The vast majority of original American newspapers from the 1870s on have been destroyed and replaced by microfilm —appears to be correct.” (Silverman, 2015, p370) and in 2015 Nora Kathleen wrote in the Newspaper Research Journal on the topic of microfilm and newspaper archives and what’s happening with the microfilm archives today.

“Microfilm was declared the saviour of newspaper preservation, and by 1946 the Bell & Howell Company made the filming of newspapers a major part of its business. But microfilm poses its own preservation problems. Acetate-based film, which was used up until the 1980s, deteriorates when not stored at the proper humidity and temperature, resulting in the loss of information captured on the film. In most cases, the original issues from which the acetate microfilm was made were discarded” (Kathleen, Nora, 2015, p292)

In contrast, Paul Otlet said often that one must not “discard printed documents”. For him the original was as important, microfilm was only a way of distributing knowledge. Now it seems that the decision to transfer the newspaper to microfilm was too optimistic for a long-term solution, as microfilm deteriorates just as normal film. It is subject to vinegar syndrome: “…a pungent vinegar smell (hence the name), followed eventually by shrinkage, embrittlement, and buckling of the gelatine”(The National Film Preservation Foundation, 2015, Online)

MEMEX

30 years after Otlet, the American Vannevar Bush came up with a new concept for information storing and retrieval machine that he called the MEMEX. Bush, an American inventor, engineer and the headed the U.S. Office of Scientific Research and Development during World War Two.

He wanted to use the new technology being developed to make sense of the information explosion happening at that time. The editor of The Atlantic wrote about Bush and the MEMEX: “For years inventions have extended man's physical powers rather than the powers of his mind. Trip hammers that multiply the fists, microscopes that sharpen the eye, and engines of destruction and detection are new results, but not the end results, of modern science. Now, says Dr. Bush, instruments are at hand which, if properly developed, will give man access to and command over the inherited knowledge of the ages.” (The Editor, 1945, Online)

The MEMEX was supposed to store books, records and other forms of communication into a mechanical device, which we would now call a computer, but envisioned before the invention of the microchip and it will all be connected by providing “links” between the content; something that for him would make access to information better than the traditional paper-based archive. It was intended to fit inside a machine the size of an office desk. Bush describe the function of the MEMEX in his essay As We May Think: “In one end is the stored material. The matter of bulk is well taken care of by improved microfilm. Only a small part of the interior of the MEMEX is devoted to storage, the rest to mechanism. Yet if the user inserted 5000 pages of material a day it would take him hundreds of years to fill the repository, so he can be profligate and enter material freely.”(The Editor, 1945, Online) This will for him greatly increase the capacity and access to the information, where massive archive of books can be combined with sound and movies.

“Consider film of the same thickness as paper, although thinner film will certainly be usable. Even under these conditions there would be a total factor of 10,000 between the bulk of the ordinary record on books, and its microfilm replica. The Encyclopaedia Britannica could be reduced to the volume of a matchbox. A library of a million volumes could be compressed into one end of a desk. If the human race has produced since the invention of movable type a total record, in the form of magazines, newspapers, books, tracts, advertising blurbs, correspondence, having a volume corresponding to a billion books, the whole affair, assembled and compressed, could be lugged off in a moving van. Mere compression, of course, is not enough; one needs not only to make and store a record but also be able to consult it, and this aspect of the matter comes later. Even the modern great library is not generally consulted; it is nibbled at by a few.” (The Editor, 1945, Online) When Bush came up with the idea, the world was just done with WW2, and he wanted to change and enlighten people with information by making use of the advancements of the new technology just developed. “The world has arrived at an age of cheap complex devices of great reliability; and something is bound to come of it.” (The Editor, 1945, Online) During and following WW2 there was a large build-up of the military industrial complex. Bush worked on projects like the Manhattan Project in and on other military systems.

The MEMEX was never built, but it did inspire psychologist, computer scientist and early pioneer of cybernetics J.C.R Licklider. Licklider foresaw the future of the computer, and the Internet and, like Bush, wanted to change society for the better with the help of information technology. Katie Hafner, cites Licklider in here book Where Wizards Stay Up Late: The Origins Of The Internet, on his ideas for the future. “...in not too many years, human brains and computing machines will be coupled . . . tightly, and that the resulting partnership will think as no human brain has ever thought and process data in a way not approached by the information-handling machines we know today.”(Hafner, 1998, p22)

Bush and his work also inspired engineer, and early Internet pioneer, Douglas Engelbart, the inventor of the computer mouse, the graphical user interface, video calling and file sharing. He is most known for his public demonstration of his inventions, in what have been called “The Mother of all demos” in December 1968 at the Computer Society's Fall Joint Computer Conference in San Francisco.

Bush also inspired Ted Nelson. Nelson was a pioneer in the field of information technology and developed the concept of hypermedia with Project Xanadu. An early concept for something that would later be named the Internet. What all these individuals had in common was that they wanted to create a new society based on connectivity and feedback by the means of the new field of “Cybernetics” Cybernetics is an idea that took hold after WW2, a discipline of treating everything as a system, a system that can be regulated and controlled with the help of technology.

Bytes

Not before the late 1970s and the widespread commercialisation of the computer to individuals, through the development of the personal computer, did the issue of personally generated information on digital formats became a topic. Before this, the users of these technologies were large companies and institutions. In contrast to Paul Otlet and his Mundaneum, which was an institution, in the 1970s mass computer storage of information moved into people’s private homes, together with the institutional problems of storage.

Katie Hafner describes digital information as: “Unlike analog systems, digital technologies essentially convert information of all kinds, including sound and image, to a set of 1s and 0s.” (Hafner, 1998, p37)

The nature of digital information compared to printed, is that it is not fixed, it is always being copied from one place to another, there is no “original file”, where as in photography there is one negative, one original. By moving a document form one place to another, its existence is copied. Henry Warwick, writer and assistant professor at the RTA School of Media at Ryerson University in Toronto writes about the nature of digital information in Radical Tactics of the Offline Library: “Computers, by their nature, copy. Typing this line, the computer has copied the text multiple times in a variety of memory registers. I touch a button to type a letter, this releases a voltage that is then translated into digital value, which is then copied into a memory buffer and sent to another part of the computer, copied again into RAM and sent to the graphics card where it is copied again, and so on. The entire operation of a computer is built around copying data: copying is one of the most essential characteristics of computer science. One of the ontological facts of digital storage is that there is no difference between a computer program, a video, mp3-song, or an e-book. They are all composed of voltage represented by ones and zeros. Therefore they are all subject to the same electronic fact: they exist to be copied and can only ever exist as copies.” (Warwick, 2014, p9)

The Floppy Disk

The Floppy disk was invented in 1967 by David L. Noble at IBM as an easy way to input information with a portable format to their new System/370 machines. The format has existed in numerous versions since its creation, the most successful being the 8, 5 and 3½- inch versions invented by SONY in the mid 1980s. It was not before the success of the personal computer systems in the late 80s that most people came to know the floppy disk as a way to store and share information, and not just something for major institutions and companies. Historian and activist Jason Scott wrote about the issue of old floppy disk on his blog post Floppy Disks: It’s Too Late. “There are libraries, archives and collections out there with floppies. They probably never got funding or time to take the data off – there’s a great chance the floppies are considered plain old acquisition items and objects, like books or a brooch or a duvet cover. They’re not. They’re temporary storage spaces for precious data that has faded beyond retrieval.” (Scott, 2011, Online)

The floppy disk contains a plastic disk coated with a magnetic oxide coating. As it is magnetic, it is sensitive to magnetic fields, which is how the information is stored, but it may be to late for the floppies as times goes by as Jason Scott described. “I’m telling you the days of it being a semi-dependable storehouse are over. It’s been too long, too much, and you’ve asked too much of what the floppies were ever designed to do. If you or someone helping you gets data off of it, then it’s luck and chance, not engineering and proper expectation. A lot of promises were made back then, very big promises about the dependability, and by most standards, those promises came out pretty darn good – it has often been the case of extracting data from floppies long after the company that wrote the software, that made the computer, that manufactured the disk drive parts, and manufactured the disk have gone into the Great Not Here.” (Scott, 2011, Online) The reality is that the magnetic oxide coating has a limited life time on how long it keeps the information, so even with the machines on hand, to really get the information off the floppy, there still needs to be electric charge in the oxide coating. The coating is so fragile, you can delete the information with a fridge magnet or by putting you phone next to it, its not a safe place for any information. Ted Jensen wrote about the frailty of floppy disks in an old computer magazine The KAY*FOG Online Magazine preserved by Jason Scott on the website Textfiles.com.

Unlimited protection against a hostile world. (Tech blog, 2008, Online)

Unlimited protection against a hostile world. (Tech blog, 2008, Online)

“Someone once raised the question of whether it makes sense to re-copy masters or back-ups from time to time to make new backups. My initial reaction was that I didn’t think it was worthwhile. Having given it some thought, however, it might not be a bad idea. If there is a degradation that takes place with time on an untouched back-up as it sits on the shelf, re-copying does in fact restore the information to a more pristine state and thus acts as added protection against the probability of losing your data.” (Jensen, mid 1980s,Online)

The floppy is now seen as a nostalgic relic, but just as the game cartridge for a video game system references the 8-track tape, the floppy disk is still referenced by its shape and looks in later optical formats such as Mini Disc (a format also made by SONY). The floppy lives on as the symbol for “saving”, as it does in Word processing software. And the actual disks are still being used on in some places, mostly in old computer systems that still exist in some industries. In some governments, floppies are still used for certain functions, as in Norway where files of patients are all sent manually in the post on floppy disks as a way to swap patients’ data between doctors and hospitals. Magnetic storage has not been the only physical format. Optical storage has existed for a while now, the most well know optical format is the Compact Disc. Its storage size of 650mb was often larger then that of hard-drives. CDs were introduce as an audio format: “CBS released the world’s first commercially available CD, a reissue of Billy Joel’s 52nd Street, in Japan in October 1982.” (Lynskey, 2015, Online)

Compact Disc

The modern plastic Compact disc was invented as a format to replace vinyl and was made as joint venture by Dutch company Phillips and Japanese company SONY. It was proposed as a better format compared to existing format in storage size, sound quality and durability. There was a big emphasis on the durability of the format and its resilience to scratching was often highlighted. This focus made one of the engineers at Philips annoyed when the “durability” of the compact disc were promoted, journalist Dorian Lynskey writes in his article How the Compact Disc Lost its Shine makes clear. “We should not put emphasis on the fact it will last for ever because it will not last for ever,” “We should put emphasis on the quality of sound and ease of handling.” (Lynskey, 2015, Online)

The Compact disc is two layers of plastic polycarbonate and a layer of foil in the middle. Lasers indent the surface lacquer with microscopic pits. The Compact disc inspired interactive fiction with its later versions of the CD-ROM; it promised a new way of experiencing media and things that used to be in print now moved over to this new style of interactive media – CD-ROMs.

One of these experiments in publishing was from the British design studio 8vo, they published eight issues of their magazine, Octavo, a graphic design magazine that was true to this life of experimenting with the new type of publishing. Editor Hamish Muir later recounted the story in their book 8vo: On the Outside. “There were several Compact disc title available. These were mostly educational encyclopedic collections which used the (then) massive storage capacity of a Compact disc, 650MB (as opposed to a floppy disk of 2MB, or typical computer hard drive of 80MB), to deliver sound, text and moving image via user interface to a computer screen. (Muir, 2005, p384) Another problem is the files themselves, as digital files are compatible to the current programs and system as they where designed, they often can’t keep up with current version of programs and systems. “Octavo 92.8 was designed to run on a minimum specified Mac with 68020 processor, 4MB of RAM, a colour screen of 640x480 pixels displaying 256 colours. Typical, this would have been a Macintosh LC. [...] The irony is that the pace of change of technology has left Octavo 92.8 largely inaccessible. (Muir, 2005, p386)

The optical discs systems, are all subject to the same issues. They easily scratch; they break and are affected by temperature and oxygen. Old Compact discs will often turn yellow, because of the layers between the plastic and metal separates and the foil comes in contact with oxygen, and also: “In 1999 it was discovered that certain mushrooms of the Geoterichum variety (used in cheese making) can damage compact disks” (Baez, 2008, p261 )

Hard-Drive

The hard-drive has been a part of the computer through much of its history. It was first used in 1950 and was invented by IBM. But it did not reach consumer computers before the late 1980s. Inside a normal hard-drive there is a spinning disk, often aluminium or glass coated, with a metallic oxide coating that spins around few thousand revolutions per minute in a metal casing, often referred to as a platter-based hard-drive. The read and write needle floats on a cushion of air where it reads and writes on the metallic coating on the platter.

A common error effecting platter-based hard-drives is from shock damage, often leading to damage on the surface of the spinning plates, often referred to as the “click of death”, other failures include faulty circuit boards or corrupted sectors, the ball bearings inside the hard-drive that can fail, as the oil that keeps them rolling dries up. Computer recover companies can recovery around 90% of hard-drives. But the future failures will come from the metallic oxide itself, metallic charge has a finite life, there will come a time when the charge is lost even on perceivable working drives.

The average lifespan for a hard-drive is four years, but even with old drives there is possibility for recovery with the right procedures. “The challenges of maintaining digital archives over long periods of time are as much social and institutional as technological”, reads a 2003 NSF and Library of Congress report. “Even the most ideal technological solutions will require management and support from institutions that in time go through changes in direction, purpose, management, and funding.” (Broussard, 2015, Online)

Currently, the SSD or Solid State Drive is taking over the market for hard-drives. Their big selling point being more shock resistance and a faster read-write speed. But is it better? Currently there is a 90% recovery rate on the old magnetic hard-drives, but SSD there is only a 70% recovery rate on dead drives, according to figures stated by the Dutch data recovery company Stellar in Utrecht.

Chapter Two

The Cloudy Commercial Complex

"It's stupidity. It's worse than stupidity: it's a marketing hype campaign," - Richard Stallman (Johnson, 2008, Online)

”We mustn’t be so gullible as to imagine Facebook and Google as the incoming platform rulers of the world. They are merely early insignia of a new paradigm that is only just unfolding. The day we log on to their far more powerful successors, we will find that their current supposed power was a mere joke in comparison.” (Seeman, 2015, p57)

The commercialisation of the internet began in the early 1990s, with larger investment in infrastructure giving way to high speeds that made the idea of external storage a reality, This gave way to the notion of the “cloud”, a term pushed on the public throughout the media, from names of services to the news media. But what actually is the cloud?

When you ask people what the “cloud” is people may imagine something floating in the sky. The problem is that most people don’t know what the cloud is. The “cloud”, in the sense of external information storage, is not a new concept, IBM has been a proponent of centrally located data processing since the 1950s. Then the focus was on government and defence. The term “cloud computing” is something rather new, and was not commonly used before the 2000s, but it can be traced back to a meeting at the offices of the computer company Compaq in 1996. “A Technology Review article in 2011 suggested the oldest use of "cloud computing" was at a 1996 meeting of Internet and startup-company executives at Compaq offices in Houston, who's imagineering described the universe being transformed by the Internet as one in which "'cloud-computing' enabled applications" would become commonly available via the web.” (Fogarty, 2012, Online)

One early version of free online storage was created in 1999 by Yahoo. They called the services “Yahoo! Briefcase”, it gave users 30MB of free storage on Yahoo servers, people where able to access the file as long as there was an internet connection, the services was shut down in March 30, 2009 in a statement Yahoo stated the reason “usage has been significantly declining over the years, as users outgrew the need for Yahoo Briefcase and turned to offerings with much more storage and enhanced sharing capabilities,” (Meyer, 2009, Online) One of the well known cloud services for file storage today is Dropbox. Dropbox started in 2007 in San Francisco and the company now give away for free 1GB of online storage with the possibility of a paid upgrade. But why? How can someone just give away things for free?

The aim is market share and not a permanent archive, their own user agreement states that in the end, you and not them, are responsible for your data. “You’re responsible for backing up the data that you store on the service. If your service is suspended or cancelled, we may permanently delete your data from our servers. We have no obligation to return data to you after the service is suspended or cancelled. If data is stored with an expiration date, we may also delete the data as of that date. Data that is deleted may be irretrievable. “ (Broussard, 2015, Online)

This disregard for their users’ information is not unique to Dropbox, all of the other cloud services have a similar policy. In the end only you can fully take responsibility for your files: “all major cloud storage services refuse to guarantee the safety of any data uploaded to their servers. Dropbox, Box, RapidShare, Google Drive, Amazon Cloud Drive, Microsoft SkyDrive… not one of them will guarantee the safety of your data. “ (Van Camp, 2011, Online) With “the cloud” there is a risk that services can shut down without prior warning.

Companies do and will not guaranteeing the safety of data people entrust them keep safe, the immense trust people have in digitizing is misplaced, So what is the impact in the future when Facebook or Whatsapp are gone? One example can be seen in the demise of the image platform Tabblo. Tabblo was an online platform for image storing and sharing. It was launched in 2005 and came to an end after Hewlett-Packard bought up the company and ended its service in 2007. Tabblo’s impact on people can be seen from the demographic they marked themselves to. They often targeted young families with kids. Tabblo is one of many company killed off by profit-driven market strategy, done way with something often called a “Acqui-hiring”. This is when a company buys a company and fires its employees and rehires them in the new company. It is a common way of buying up employees or “talent”, as it is called in Silicon Valley, to keep them away from legal issues the old company may have had, as that old company is terminated.

If it was not for small activist such as Ned Batchelder, former Tabblo engineer and the Archive Team, the story and memory may have been lost for most people.. Jason Scott, main activist behind Archive Team stated in his keynote, The House is on Fire, the Fire Trucks are on Fire, The Fire is on Fire, at the Harvard Law School, a story of a Tabblo user. “… this is a particularly tragic one , this is a guy with photos watched his house burning down and he says yeah I lost everything but luckily I have my five thousand pictures on Tabblo and a month later they deleted them all…” (Caliorg, Online Video, 2014)

Tabblo is not a unique case, there have, and will be, dead services and companies in the future. How long the current big services like Facebook and Instagram will last we cannot predict, but a careless view on the content and how it is stored is not the way to go for future access. As the drives being used are the same as on your own machine, they are subject to the same laws of nature as every hard drive. There is monitoring of the drives and broken or unstable drives will be removed and replaced. But this stable system will only work if someone is monitoring the system. Shifting terms of the services are an issue, the apparently “better” solution in the form of user interfaces, services and service plans often mixes up the terms of the services. Something that works often can be put to one side for something new and better. Norwegian broadband company Telenor shut down its older free web-hosting service home.no, that contained websites dating back to 2000. It was an online free web-hosting services, their reason was too move people over to its new Home. Cloud services. Even with some of their users, often people doing ancestry research complaining. and the national archive argument against it, because for Telenor it was “just old websites”, the services was shut down October 31th, 2016. In the past ten years the use of social media networks has reinvented the way we create information, along with why and how we create information. One point Wolfgang Ernst addresses in Digital Memory and Archive is “the so-called cyberspace is not primarily about memory as cultural record but rather about a performative form of memory as communication.“ (Wolfgang, 2013, p99)

Chapter Three

My Hard-Drive Died Along With My Heart

“Is every tweet really worth saving? All I can say, is we won't know for a while.”. (Pardes, 2016, Online)

We record more and more of our daily life, our hard-drives are filled with images, music collections, ephemeral collections of digital memories, so how are people dealing with the loss of information after devices fail? We know from the previus chapter that sometimes online services like Tabblo can shut down with no prior notice, but this can happen at home aswell, we know the unstable nature of hard-drives. For my graduation project at the The Piet Zwart Institute I have made the book project My Hard-Drive Died Along With My Heart, the book contains online forum posts and tweets from social media on the subject of data loss. This is from the perspective of people who lost information when their hard-drives crashed and then needing to deal with the aftermath.

The name of the project comes from a tweet made by @KatShambaugh “My hard drive died along with my heart #help”. By reading the book you will be able to read your way through time, from month to month and across the years, from 1991 to 2016. The topics range from lost iTunes music to more severe issues, such as the loss of valuable information and research, like this post from USENET user Mark Harries. “This is a *serious* cry for help... if you have any advice, [..] My hard drive is dead and - more important than the fact that this is my computer – this computer is my wife's lifeline of communication to treat my son. This is the most important point – I have a 3 year old autistic boy (Alex). My wife (Kelley) spends many hours a day doing research – dietary interventions, applied behavioural analysis, social stories, enzymes” (Harries, Online, 2003)

When technology fails, people react in different way. One person that did change his habits and relationship to his hard-drives is Robert Sagi. The Rotterdam based music lover told me about his experience with hard-drives in his apartment in Rotterdam. “I had a big music collection, one that I collected over a period of eight years, countless hours of finding rare version of songs, on services like Napster , but also traded with friends. But after a while I had one drive that died, then another… I had around three drives that crashed totally for me in a short period of time. You get really tired of constant maintain the machines, reinstall the operation system and after the last crash, when I lost most of my collection. I decided to stop collecting mp3s and instead do the efforts of collecting vinyl instead, now I can see the music on the shelf and I know what I got now, your discussion just reminded me of my friend, he lost probably around 10.000 photos, he said that his girlfriend formatted the drive by accident, they nearly broke-up over that incident, In the end, its just files, but the emotions are real. ” (Robert, Interview, 2016) The people behind some of my tweets in my collection have all needed to react to the issues of data-loss, like the Twitter user @MuisiCrazy, He explained his experience to me after his hard-drive failed over Twitter direct messenger.

Thomas: How did you discover that your hard-drive died? MuisiCrazy: The hard drive died suddenly. My computer just froze while on, and that was it. DEAD. T: What was the first feeling you got after realising your data was gone? M: Of course I was devastated, more so because I hadn't backed up in a long while, so yeah , a lot was lost T: Did you try to recover the data yourself or with the help of experts? M: No i didn't it was completely fried, so I didn't bother to attempt recovery. T: Has your opinion on how and where your data is stored changed since losing your hard drive? M: Yes, a lot. I back up weekly now, because that experience is not something I want to repeat, T: Are you afraid that you may lose your data in the future? M: Yes, I mean that's always a possibility with these things.. so I guess it can always happen again, you just hope it doesn't and back up data. (@MuisiCrazy, Interview Online, 2016)

Computer files are more than just trinkets of the past; they actively can remake our understand of the past. French philosopher Jacques Derrida talks about this issue in his text “Archive Fever”. The invention of the Internet has intensified a wave of recording and archiving that began in the 20th Century and professor for media theory Wolfgang Ernst addresses this in Digital Memory and the Archive. “According to Jacques Derrida, ‘The Twentieth Century, the first in history to be exhaustively documented by audio/visual archives, found itself under the spell of what contemporary philosopher called 'archive fever', a fever that, given he World Wide Web's digital storage capacities, is not likely to cool any times soon.” (Wolfgang, 2007, p137)

How we relate to our storage mediums can from one perspective been seen as a supplement to our brain, Canadian media theorist Marshall McLuhan stated in Understanding Media: “We become what we behold. We shape our tools and afterwards our tools shape us" (McLuhan, 1994, p xvii). So how have the storage devices and services we use today shaped our memory, and what is the emotional impact on us when they fail? The impact these devices have is not just physical but also mental, it changes the way we remember collective memory. There have been a long standing idea that computer memory replicates the way human memory works, but, as José Van Dijck maintains, “American psychologist Susan Bluck contends that autobiographical memory has three main functions: to preserve a sense of being a coherent person over time, to strengthen social bonds by sharing personal memories, and to use past experiences to construct models to understand inner worlds of self and others.” (Van Dijck, 2007, p3) What we record on various media can change our perspective on the events, relaying on short snapshots in a medium turns into what we remember. How a medium alters our perspective on events is something French philosopher and cultural theorist Jean Baudrillard discussed in The Gulf War Did Not Take Place. In this collection of essays he examines how people remember the first Iraq War through media, the memory of events is constructed through the media. This leads us to ask, is documentation of daily life helping us or just remaking our memories.

Media as memory constructor is central to Van Dijck’s argument: “The endless potential of digital photography to manipulate ones self-image seems to render it the favourite tool for identity formation and personal memory construction.” (Van Dijck , 2007, p106) One key issue is people’s understanding of technology, of what the devices and services really are, how do they work? Some will maybe describe their understanding in the same way as some will describe magic. The famous Science fiction author Arthur C. Clarke stated in 1969: “any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” (Feigelfeld, 2015, Online) One of the reasons for people’s lack of understanding of technology is due to what the industry calls “black boxing”. In the computer industry, the term is described as “ a usually complicated electronic device whose internal mechanism is usually hidden from or mysterious to the user” (Merriam Webster, Online). When we don’t understand the nature of storage technology, how can we really take the best possible action to storage our data.

Conclusion

“The present is shadowed by the inverse omens of its past”. (Wolfgang,2007,p170)

No perfect solution

At the beginning of this thesis I asked the question: “is there any such thing as a perfect storage technology?” The answer is clear, history tells us there is no permanent solution. The notion of a permanent solution is highly utopian, pushed on us by the creators of storage systems. Over-promising and under-delivery has applied to every successive format.

Technological thinking holds that for every problem we can invent something to fix it, but the solutions always create new problems. The computer industry have since the 1980s actively moved into the domestic sphere, the problems that institutions have been struggling with for decades are domesticated, becoming something individuals now have to deal with. But the digitization of the archive proceeds with full force in institutions and its seen as an “easy” solution for space saving and other economic problems. For instance: “Finland's National Archives is currently celebrating its 200th anniversary. At the same time, legislation is being finalised that will enable the Archives not simply to digitise its documents but to dispose of them too. […] According to the Ministry for Education and Culture, 40 per cent of the National Archives' budget goes on bricks and mortar. The prime motivation behind digitisation is therefore cost-efficiency, especially at a time of severe public sector cuts.” (Jeffreys, 2016, Online) this fetishization of digitisation is something Lev Manovich describes this issue in his book The Language of New Media: “In the 1990s, when the new role of the computer as a Universal Media Machines became apparent, already computerized societies went into a digitizing craze, All existing books and videotapes, photographs, and audio recordings started to be fed into computers and an ever-increasing rate. (Manovich, 2001, p224)

Digitizing is supposed to make paper obsolete, computers are going to take over the printed book, and paper will be a thing of the past, but did it happen? In Post-Digital Print Alessandro Ludovico observes: “We can trace the actual expression ‘paperless office’ back to an article titled The Office of the Future, published in Business Week in June 1975.” (Ludovico, 2013, p25) What often survives in a society is culture. We know the ancient texts from Greece not because they were stored in a single place, but because they were spread around, copied and remixed into new texts.

When a new medium arrives, it always leaves the old on the dust, which is deemed of lesser value. But on those formats, there lies a snapshot of society from the past. What can future society learn from the present if there is no fragments to be found? The mystification of technology has hindered people's understanding of the nature of what they are using. This engenders a careless attitude towards where and how we store information. Its hard to say what dangers exist in the future, its impact is on the individual level. From what we know of how human memory works, it does not remember everything in detail, but makes sense of the world around us. "In spite of current project designers projections, the ultimate goal of memory is not to end up as a Powerpoint presentation on your grandchild's desktop; the ultimate goal of memory is to make sense of ones life. (Van, 2007, p169)

Information entropy

It is hard to say what is valuable, which is good reason not to be careless. What we assume to be valuable will not necessarily be what interests people in the future. Paul Otlet, for instance advocated the use of microfilm but he did not support throwing the original documents away. To maintain a system, you need to put energy into it, this applies to any system, from people to the economy. In the social context, a system fails first because of the lack of people to take care of it. We see that from the Library of Alexandria to the Tabblo. To connect information and energy is not something new. Mathematicians Claude E Shannon and Warren Weaver wrote on this topic in the The Mathematical Theory of Communication in 1948 “to those who have studied the physical sciences, it is most significant that an entropy-like expression appears in the theory as a measure of information" (Shannon, 1948, p11) Entropy can be described as if things, left to themselves will, over time, disperse. It takes energy to keep things in order. Entropy, in relation to information, is a term derived from Thermodynamics.

Every format invented is stated to be secure, but every format needs to be maintained. To maintain the format you have to use energy. The loss of energy used to maintain it, is the information lost. So what can we learn?, That nothing is forever, nothing is permanent, and its more the mentality towards storage that needs to change. Although we may have changing formats, the issues still exists, so we must remember that “memory is an active process, not static. A memory must be held in order to keep it from moving or fading. Memory does not equal storage.” (Kyong,2008,p164) Points of discussion: What we may do?

We need to change our mentality toward temporary storage and actively maintain our collections. We need to take it seriously if we are ever going to keep anything of what we may think is important. Technology companies are deciding more and more what to keep and what to delete, we are no longer in charge. We have a belief or ideology of permanent storage systems, but this ideology is fundamentally at fault. We remember on behalf of the future, we chose what do keep, this process is discriminatory, and in so doing we make assumptions what they may think. So lets be less discriminatory about what we keep for some information survives by being remixed and copied over time, this led to a lot of information being cut up and dispersed into culture.

Images and text can live on, but often the context disappears. We lose something, but keep what is deemed most important. It is a compromise for culture. Information that is not meant to be preserved is often what ends up surviving...but Its not really a given. The term Jason Scott has used for this is “ambient archiving”. Ambient Archiving is when things, often ephemeral things get saved from the trash, often because of one individual will give value to what the status quo do not value, preserving something in contrast to what is perceived as important. In this way things are relayed on, by putting energy into the effort. But for the future, we must not put all our eggs in one basket, as the risk of it failing is high and the ramifications are huge, and its effects will be felt for a long time. "Memory is no longer what we remember it to be, but then, memory probably never quite was how we remembered it and way never be what it is now. The present is the only prism we have to look thought to assess memory's past and future, and it is important we look through this contemporary prism from all the possible angels to appreciate memory's complexity and beauty.” (Van, 2007,p 182)

Biography

- Abreu, Amelia (2015) The Collection and the Cloud, The New Winquiry [Online] Available: http://thenewinquiry.com/essays/the-collection-and-the-cloud/ .(Accessed:10.10.2015)

- A. Hansen, Kathleen, Paul, Nora (2015) Newspaper archives reveal major gaps in digital age, Newspaper Research Journal.

- Bush, Vannevar (1945) As We May Think, The Atlantic.com [Online] Available: http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1945/07/as-we-may-think/303881/ (13.11.2015)

- Baez, Fernando (2008) A Universal History of the Destruction of Books: From Ancient Sumer to Modern-day Iraq, Atlas & Co

- Caliorg (2014) Keynote I - Jason Scott - The House is on Fire, the Fire Trucks are on Fire, The Fire is on Fire, [Youtube], 15 August. Available: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qh7EARxkxoU (Accessed: 08.09.2015)

- Gabrys, Jennifer (2007) DIGITAL RUBBISH a natural history of electronics, Paperback , United States of America, The University of Michigan Press

- Hafner, Katie (1998) Where Wizards Stay Up Late: The Origins Of The Internet, New York, Simon & Schuster

- Holt, Mark Muir, Hamish 8vo - On the Outside (2005), London, Lars Muller Publishers

- Jansen, Ted (mid 1980s) EVERYTHING YOU EVER WANTED TO KNOW ABOUT FLOPPY DISKS....... BY Ted Jensen FROM: ARTICLES, "The KAY*FOG Online Magazine."[Online] Available: http://textfiles.com/computers/floppies.txt (Accessed 23/08/15)

- Johnson, Bobbie (2008) Cloud computing is a trap, warns GNU founder Richard Stallman [Online] Available:https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2008/sep/29/cloud.computing.richard.stallman .(Accessed:17.02.2016)

- Jason, Scott (2011) Floppy Disks: It’s Too Late , http://ascii.textfiles.com [Online] Available: http://ascii.textfiles.com/archives/3191 (12.12.2015)

- Jeffreys, Tom (2016) Ending the paper trail, thelongandshort.org [Online] Available: http://thelongandshort.org/society/future-of-archiving (Accessed: 17.05.2016)

- Johnson, Bobbie (2008) Cloud computing is a trap, warns GNU founder Richard Stallman, The Guardian.co.uk [Online] Available: https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2008/sep/29/cloud.computing.richard.stallman (04.01.2016)

- Kittler, Friedrich A. (1999) Gramophone, Film, Typewriter, Stanford University Press

- LaFrance, Adrienne (2015) Raiders of the Lost Web, Theatlantic.com [Online] Available: http://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2015/10/raiders-of-the-lost-web/409210/ (Accessed: 24.11.2015)

- Lynskey, Dorian (2015) How the compact disc lost its shine, The Guardian.com [Online] Available: http://www.theguardian.com/music/2015/may/28/how-the-compact-disc-lost-its-shine?CMP=fb_gu/ (Accessed: 01.06.2015)

- Merriam Webster (2016) Merriam Webster [Online] Available: http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/black+box (Accessed:18.03.2016)

- Meyer, David (2009) Yahoo drops its Briefcase [Online] Available: http://www.cnet.com/news/yahoo-drops-its-briefcase/ .(Accessed: 05.03.2016)

- Mike Harries (2003) 'UPDATE on my Dead Hard Drive (was HELP ME PLEASE! MY HD'S DEAD!), groups.google.com [Online] Available: https://groups.google.com/d/msg/aus.computers.mac/9CMovhsW5oc/iB-ZbdvSe5oJ (Accessed: 04.03.16)

- Manovich, Lev, (2001) The Language of New Media, United States of America, The MIT Press

- McLuhan, Marshall, (1994) Understanding Media The Extensions_of_Man, United States of America, The MIT Press

- National Film Preservation Foundation (2015) Vinegar Syndrome, [Online] Available: http://www.filmpreservation.org/preservation-basics/vinegar-syndrome (Accessed: 06.02.2016)

- Pardes, Arielle (2016) How Digital Storage Is Changing the Way We Preserve History [Online] Available: https://www.vice.com/read/how-digital-storage-is-changing-the-way-we-preserve-history (12.05.2016)

- Parikka, Jussie (2012) What is Media Archaeology, United States of America, Polity Press

- Seeman, Michael (2015) Digital Tailspin Ten Rules for the Internet After Snowden, Amsterdam, INC

- Shannon, Claude E. , Weaver, Warren (1948) The Mathematical Theory of Communication, University of Illinois Press

- Truefilms (2007) The Man Who Wanted to Classify the World, http://truefilms.com/ [Online] Available: http://truefilms.com/the-man-who-wan/ (Accessed: 14.02.2015)

- The Enduring Ephemeral, or the Future Is a Memory Author(s): By Wendy Hui Kyong Chun Source: Critical Inquiry, Vol. 35, No. 1 (Autumn 2008), pp. 148-171 Published by: *The University of Chicago Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/595632 . Accessed: 22.09.2015

- Van Camp , Jeffrey (2011) "Why should we trust Google Drive, or any cloud storage service? [Online] Available: http://www.digitaltrends.com/computing/how-can-we-trust-google-drive-or-any-cloud-storage-service/ (24.11.2015)

- Van Dijck, José (2007) Mediated Memories in the Digital Age, United States of America, Stanford University Press

- Warwick, Henry Radical Tactics of the Offline Library, (2014), Amsterdam, INC

- Hawk, Thomas, (2006), tabblo, Screenshot, [Online] Available:, https://www.flickr.com/photos/thomashawk/147040363 (Accessed: 10.05.2016)

- O, Von Corven, (20xx) , The Great Library of Alexandria, Illustration, [Online] Available: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ancientlibraryalex.jpg. (Accessed: 27.05.2016)

- Tech blog, (2008), Nine awesome computer ads from the 70s and 80s, Illustration [Online] Available: http://royal.pingdom.com/2008/11/25/nine-awesome-computer-ads-from-the-70s-and-80s/. (Accessed: 13.04.2016)