User:Pedro Sá Couto/Reading, Writing & Research Methodologies 3rd

Dusan Interview

Bio

Dušan Barok is a researcher, artist, and cultural activist involved in critical practice in the fields of software, art, and theory. Graduated in information technologies from the University of Economics of Bratislava, he then moved to the Netherlands to complete Networked Media masters course at the Piet Zwart Institute in Rotterdam, to finally land in a doctorate in the preservation of contemporary art in Amsterdam. He is best known for Monoskop (monoskop.org), a wiki for collaborative studies of the arts, media, and humanities, started in 2004 as a project to document and map media art and culture in the eastern part of Europe. It expanded toward arts and humanities to take its final form of a media library in 2012, as Dušan Barok's graduation project at the Piet Zwart Institute.

The wiki provides an indexed collection of information, materials, and links around those fields, focusing on less-known phenomena, while the parallel project called "Monoskop Log", releases digital publications to create an exhaustive archive of resources directly linked to the wiki entries. Books are available in different formats and their digitisation is done by Monoskop but also users can contribute or one can find the link to the original file usually coming from other digital libraries.

Questions

1. As the librarian of Monoskop, do you feel the responsibility to regularly share new files and improve how they are organised?

I use Monoskop almost on a daily basis, keeping trace of my focused or less focused browsing, reading and live encounters. A wiki, as a read-write website, really is a cool medium in McLuhan's sense. Its pages are never complete, they demand continuous updates, and being linked to one another, often it is a chain reaction, an idiosyncratic process of rereading and rewriting and following what others edited and contributed to the site. It is a messy process, by now a habit perhaps, with no end in sight, a compendium of temporary interests, passions and exchanges.

At the same time there certainly is a responsibility. The website has been part of Google and other search indexes and it does have a share in bringing people, ideas and things in focus, into attention. The responsibility here is to unveil, unearth what is not established, prominent, what is urgent, bring about new relations and contexts, burst bubbles. Our language and communication will always be narrative, a succession of signs, but we've made a long way from the primacy of a book as the basic unit of knowledge. Imagine you are not running a library but a search engine, operating in a field governed by the logic of an index and the mechanics of bots. Or that you are running a content farm, in the world where the only content that matters is either a massive dataset or a viral tidbit of information.

2. Digitising books involves decisions on how to manage human and non-human traces present in the physical book. When you select a book, do you follow any rules to manage those traces?

When scanning a book I try to enter at least basic metadata into the file, including title, author, producer, date of scanning and source of the volume. Many books I've scanned contain marginalia and highlights. I like to preserve them, which is part of the reason to scan in full color, albeit I am also aware that for some they can be distracting. They are usually personal, notes to self, rarely intended for a wider audience. Still I prefer to stay true to the original copy and its materiality.

I like to use old-school scanners for results have their own, perhaps by now vintage aesthetics. I say old-school because of course today it is more apt to use overhead scanners with digital cameras. Currently I am collaborating with artist Ilan Manouach, building a collection of conceptual comics [1], consisting mostly of works published in the past ten years. Ilan has built his own overhead scanner and photographs books with pages open, which opens up for a special physical experience. Rather than creating ready-to-print digital copies, these PDFs may be experienced on tablets and digital frames, emphasising the "visuality" of these works.

3. In the Monoskop catalog, we have found books such as "Umenie dnes" by Tomáš Štraus (for example, page 3, 158, and 172) where the digital copy contains marks from the physical source. When did this preoccupation start and what does it mean for you to explore the processes in the margins of readable sources?

This scan [2] was made as part of our "Unlimited Edition" series of digital editions of rare but important works from art history. The PDF file has coins, Czechoslovak crowns, placed on some of the pages, totaling the original price of a copy of the book. I think it was an attempt to address the relations between value, historicity and distribution. One thing is the virtue of bringing an out-of-print volume back into distribution, another is the radically different context in which this happens. The act of digitisation is often viewed as automated and neutral, but of course, as you said, there are many decisions involved along the line. One can clearly see it when comparing digital reproductions of a single volume made by different individuals and institutions. Our part is to question the logic of assembly line so tightly attached to the digitisation of art, knowledge and heritage.

4. Archives such as the Archive of the Avant-gardes in Dresden where you were involved, are starting to implement digital archives for their collections. However, the historical memory of the physical item with its time frame within a specific archive and its spatial position in it are not represented, showing a loss of criticism in the relation between materials, institutions, and people involved in its fruition. Do you think is it important to keep this historical information in the digital implementation of a collection?

It is by now well acknowledged that a printed document and its digital copy is not the same thing, their properties are different. But besides the politics of file formats and optical character recognition, there is a whole range of other issues which are subject to different affordances and interests in the digital domain. What struck me in researching the Archiv der Avantgarden (AdA) in Dresden was the palpability of contextual framework imposed by the institution of a collection upon included items, and the (however unintentional) role of the digital version of the collection to obfuscate this imposition. The archive follows, rather strictly, a certain structural logic, invented and applied to it by its original owner before the archive has been transformed into a public institution. The order has been inspired by and expanded upon the book 'Kunstismen' by El Lissitzky and Hans Arp [3] in which they represented some of the avant-garde movements of the era by various "isms". The collector had been active mainly from the 1960s through the 1980s this era obviously left its marks on the structure. You have to spend some time in the archive before the logic and structure really comes forth and gets revealed to you in full. It is very hard, if not impossible to let this happen in the digital realm. But this is where most people will access and experience it after the archive gets published online. There it won't be so obvious to notice that it almost solely represents male artists from the Western world and equally hard it will be to understand why, as this logic has also played a role in acquisitions. What kept on resurfacing during our research (there were about 60 researchers involved in the project) was the will of the AdA team to "fill the gaps". Here, a digital archive comes to help cover the traces as well. Once new acquisitions enter the archive, they will merge with the rest of the collection, as if they have always been there. A website seemingly erases the past and presents the current state of the collection as the ever-lasting one. The takeaway here is that a digital archive provides access to cultural memory but it tends to lack memory of itself; and while it provides access to world's memory, it tends to do so out of nowhere. What do we do about it?

5. Some of the books in Monoskop Log are linked to the digital library of origin; what is your intention in providing this kind of historical path of the file? Do you keep track of the viability of these links?

It is often about finding a right balance between acknowledging and protecting sources. When I am unsure I try to ask, although I am more happy when Monoskop serves really as one point in the path of a file so that one can trace it back to where it came from. Perhaps we can think of distribution along the lines of citation practises. As we said earlier, there is work and decisions involved in digitisation, and linking sources adds to both credit and accountability.

6. In your 2013 interview for the Neural Magazine you say that takedown notices are often a reality for Monoskop. Do you keep records of which books you were asked to remove, and by whom you were asked to do it? Do you think this kind of practice could reveal valuable information on how free access to texts is tracked by publishers and how to escape systematic control?

Yes we do keep records and try to be very open about it. As a rule, the entries on Monoskop Log are preserved even after the actual files are removed. I usually leave a note about the date and the subject who asked for deletion. This marks a part of the path of the book, even if it reaches a dead end in this case.

7. Monoskop explores the condition of digital books but it is a project also related to the evolution of art in its most contemporary and digital forms. In terms of your doctoral studies in the preservation of contemporary art, what is the relation between digital artworks and digital books? Should their processes of conservation and reproduction be addressed in the same way?

That's a good question, I haven't thought about it that way yet. As it happens, it is more straightforward to archive and preserve single files such as digital books in PDF and EPUB. This has been a crucial part of our work on Monoskop. However, many publications and other works are websites and similar assemblages of code and data, written in multiple programming languages with various software dependencies and consisting of many files and pages, oftentimes running on top of relational databases. Here we rely on the Internet Archive's Wayback Machine. When an online work comes down, one can almost always find its archived version on the Wayback Machine and this is what I usually do myself when I want to update a dead link to a website. I am aware there is too much at stake, and fields such as the preservation of software-based art do have much to offer here. Libraries where crawling and scraping meets emulation and virtualisation? Yes please!

Blurry Boundaries Workshop

INTRO

Select, annotate, analyze, scan, correct, digitize, print, read, transfer, erase, encode, curate, hack, interface, work, copy...

What libraries become possible when you transform physical books into digital files, and vice versa? When a digital copy of a book is made for a digital library specific steps are followed. Each of these steps requires a decision – to use tools and to spend time. The work involved in digitising a book is invisible and the digital version often loses its connection to the physical book and the library it came from.

We aimed to reflect upon different topics such as:

- the friction between the physical and digital book, what is lost and what is gained when you pass from one format to another.

- the physicality and contingency of these passages, the labor involved to produce those copies and its hidden position.

- the mindset of the librarian who has to choose how to produce the digital library, which format to chose and what kind of information to reveal.

- the possibility of a digital library which provides the history of the book and the people involved in its life.

- annotations which reveal information and challenge the common, static idea of the book.

FINAL STEPS

http://pzwiki.wdka.nl/mediadesign/User:Pedro_S%C3%A1_Couto/Special_Issue_9#STRUCTURE

Letter from XPUB: The Library Is Open

GENERAL INTRODUCTION

Rotterdam, 3 July 2019

Dear readers,

In the spring and summer of 2019 we developed The Library Is Open, a publication which focuses on the operations, actions, and roles of legal and extra-legal libraries. Central to this project is the community that forms around a collection of texts – the custodians of the collection and the readers.

The Library Is Open is the result of the third iteration of Interfacing the Law, an ongoing research project between XPUB and Constant (BE), which explores issues around extra-legal libraries, software and legal interfaces and intellectual property. Led by our guest editor Femke Snelting, we participated in many activities which were organised by invited guests:

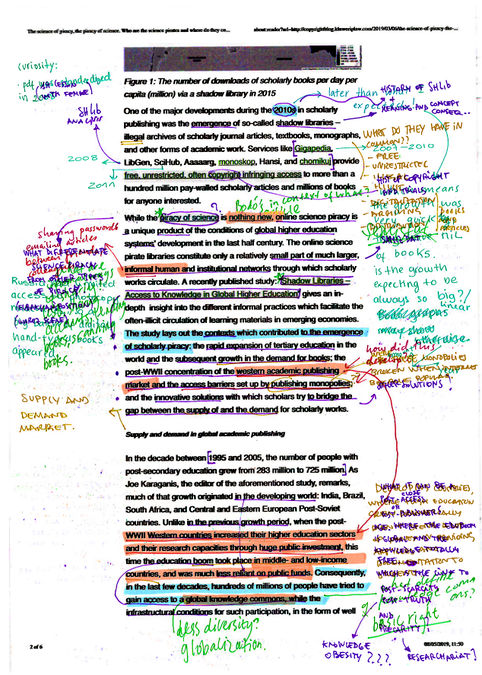

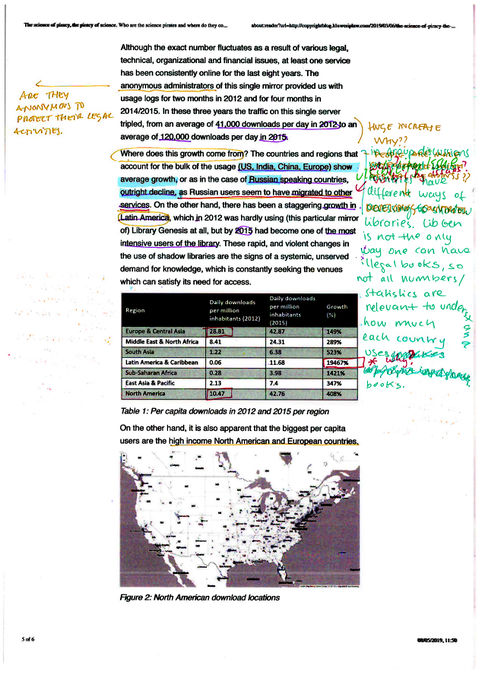

With Bodó Balázs, an economist and researcher on shadow libraries, we analysed the gargantuan dataset of Library Genesis, to determine trends which indicate access to texts and the social, geo-political and economic aspects at play

.

With Anita Burato and Martino Morandi at the Rietveld Library in Amsterdam, we discovered the subjectivity of subjects and thorny issues of classification and representation

.

With other readers, we deepened our understandings of texts through collective annotations.

With artist and researcher Eva Weinmayr, who introduced us to The Piracy Project, we examined the possible motivations and differences between pirated books and their "source".

With open-source software such as Tesseract, pdftk, and LibreOffice (and many others) we explored the technical processes used during the creation of pirate libraries, and the hidden labour involved in this.

With fellow pirates, we considered the multiplicity of roles and activities involved in maintaining various libraries, such as Monoskop, Libgen, Aaaaaarg, Sci-Hub, Memory of the World, Project Gutenberg, +++.

With Dušan Barok, the administrator of Monoskop and an alumnus of the Piet Zwart Institute, we discovered how Monoskop was initiated and how it has changed over time.

The variety of our collective sessions, and the practical exercises we performed led us to organise an afternoon of three workshops that directly address the active role of piracy, rather than simply talking about it. Encouraging small, informal, collective actions, we wanted to challenge the ordinary, hierarchical presentation of research projects in the academic context, and individual notions of authorship.

When choosing a suitable venue for our event, we decided to ask Leeszaal (in Dutch "Reading Hall") to host our workshops. Situated in a busy, multicultural area of Rotterdam, Leeszaal exemplifies many values we sympathise with, particularly open access to knowledge, and a focus on the community that uses the space, not just for reading but for many other social purposes. These values we recognise (somewhat nostalgically) as reminiscent of public libraries of yesteryear. However, the landscape today is quite different, with huge online commercial repositories of texts (e.g. JSTOR), protected by paywalls which limit access to them, and in response the emergence of "shadow libraries".

In the following pages we invite you to wander through the dilemmas, outcomes and reflections that came out of our three different workshops, and interviews with people whose work is at the centre of the issues that each workshop uncovers.

Knowledge In Action explores the roles and activities within libraries, such as selection and inclusion of books. Interview with: Dubravka Sekulić & Leeszaal staff.

Blurry Boundaries reveals the hidden processes and labour between the publishing and distribution of physical and digital books. Interview with: Dušan Barok.

Marginal Conversations highlights the sociality of texts, and how they can become conversations through collective reading, annotation and performance. Interview with: Marcell Mars & Tomislav Medak.

Yours in piracy, XPUB

12/06/2019 Inite+Event

Short text for issue webpage

Dear readers,

The Library Is Open invites you to an afternoon of workshops that make the operations within libraries visible. Join us in exploring the actions and roles of legal and extra-legal libraries (municipal, pirate, academic, +++), their custodians, and the public that form a community around collections of texts.

Simon Browne, Tancredi Di Giovanni, Paloma García, Rita Graça, Artemis Gryllaki, Pedro Sá Couto, Biyi Wen and Bohye Woo

Event Text

Dear readers,

The Library Is Open invites you to an afternoon of workshops that make the operations within libraries visible. Join us in exploring the actions and roles of legal and extra-legal libraries (municipal, pirate, academic, +++), their custodians, and the public that form a community around collections of texts.

Date: Thursday June 20th, 2019 Location: Leeszaal West Rotterdam Time: 13:30-18:00

Schedule:

- 13:30 Introduction

- 14:00 Session 1

- 15:00 Break

- 15:30 Session 2

- 16:30 Sharing moment and wrap up

- 17:00 End

- Registration is not necessary, as on arrival you will be assigned to two workshops. After the first session there will be a short break, after which the second session of workshops will begin. At the end of the event we'll have a moment to share the outcomes of the workshops all together. We'd like you to attend both sessions if possible, in order to maximise the experience.

The event is divided into three parallel workshops which will be held twice, giving participants the opportunity to encounter different experiences:

Blurry boundaries

Select, annotate, analyze, scan, correct, digitize, print, read, transfer, erase, encode, curate, hack, interface, work, copy... How do we reveal the hidden labour involved in these processes? What libraries become possible when you transform physical books into digital files, and vice versa?

In this workshop you will be a librarian converting books into machine readable files, a process involving tools, time and choices.

The Library Is Open is a participatory event developed by the Piet Zwart Institute's Experimental Publishing program as part of the research project Special Issue #9: Interfacing the Law, in partnership with Constant. Interfacing the Law is a recurring thematic project which looks at how publishing practices develop in accordance, or in dissonance with legal frameworks.

Contributors:

Simon Browne, Tancredi Di Giovanni, Paloma García, Rita Graça, Artemis Gryllaki, Pedro Sá Couto, Femke Snelting, Biyi Wen, Bohye Woo

Special thanks to:

Bodó Balázs, Dušan Barok, Anita Burato, André Castro, Aymeric Mansoux, Michael Murtaugh, Martino Morandi, Leslie Robbins, Steve Rushton, Amy Suo Wu, Eva Weinmayr

5/06/2019 Planning Workshops w/ Steve

https://pad.xpub.nl/p/IFL_2019-06-05

Physical ≥ digital — (Pedro, Bo, Tancre) https://pad.xpub.nl/p/physical_digital_workshop

22-05-2019 — Outlining content of issue launch 01

https://pad.xpub.nl/p/may_project_proposal

https://beta.etherpad.org/p/22_05_2019

http://pzwiki.wdka.nl/mediadesign/Calendars:Networked_Media_Calendar/Networked_Media_Calendar/22-05-2019_-Event_1

PHYSICAL LIBRARY

↓

CHOOSE A BOOK

↓

STEP 0 — WRITING A PERSONAL DESCRIPTION

- ACTION — Write a small description on why did you choose this book, what is it about, personal anecdotes possibly.

- WHAT DO WE WANT TO ACHIEVE — Documentation of the subjective experience

- OUTPUT — A .txt file

↓

STEP 1 — ANALYZING THE BOOK

- INPUT — Book from a shelf

- ACTION — Document practical condition of book (e.g. dog ears/underlines/weight/paper/in what section of the library it was found/...)

- Physical condition categorization — We could make our "correct" way, this is ebay's — https://www.ebay.co.uk/gds/How-To-Correctly-Grade-Used-Books-/10000000001207186/g.html

- WHAT DO WE WANT TO ACHIEVE — Important to acknowledge what was the physical condition of the book before it turns in to the digital file. Also keeping the memory of the physical book(its condition/where it was placed/ where it cames from/ ...) when it comes to its digital implementation.

- OUTPUT — Documentation of the physical book (condition)

↓

STEP 2 — SCANNING & DIGITIZING

- INPUT — The book that we have chosen before

- ACTION — Digitize the chosen book and reflect on Dusan's marks on the labour (who, where, when, why selected/scanned/...)

- MAKE A DECISION — What do we want to add? (Aknowledgement to the labour in a visible way) or (make it hidden in the metadata on STEP 4)

- WHAT DO WE WANT TO ACHIEVE — Thinking about authorship in the context of hidden labour in shadow libraries, what are hidden accumulated labours that we don't see physically. (We can use this info in the augmented colophon/watermark/metadata/ }

- Authorship and processes of (hidden) labour, and how is the translation revealing that process (https://monoskop.org/images/d/d2/Straus_Tomas_Umenie_dnes_Pokus_o_kriticku_esej.pdf look at page 5 and )

- We can make physical watermarks that can be placed over the book when scanning

- OUTPUT — Images of the scanned book + extended colophon (wwww)

↓

STEP 3 — OCR-ING

- INPUT — Images from step 2 (with extended colophon)

- (h)ocr → .html / .html →.epub

- (h)ocr → .pdf

- ocr → .txt (Using different ocr-ing methods to have a variety in the format. ) / the ocr could not work properly + the content can be edited

- WHAT DO WE WANT TO ACHIEVE — Recognize that a digital library is built with different formats and approaches, creat outputs as pdfs, epubs, etc.

- OUTPUT — Book in a particular format (pdf, epub, html, etc), a documentation of the process (part of the metadata)

↓ {

STEP 4 — INDEXING, CATEGORIZING

- INPUT — Book from step 2

- With a script to categorize the most commonly used words / Social Interaction (discussing and making your own indexing)

- WHAT DO WE WANT TO ACHIEVE — Raise an awareness that digital libraries also demand librarian shop while there is a need for them to be managed

- OUTPUT — Categories to each book (script to look into main words) or (discussion if needed)

}

↓

STEP 5 — ADDING METADATA 'EXIFTOOL'

- INPUT — Book from step 3

- ACTION — Reveal the hidden digital colophons, and add extended colophon.

- WHAT DO WE WANT TO ACHIEVE — Create an understanding on what is being hidden from the file, what informations are in the shadow/why?

- OUTPUT — A book with extended metadata that is added + a file with the changes that were made to the metadata

↓

- STEP 6 – FINAL PDF & DIGITAL LIBRARY

- INPUT — final pdf (cover+extended colophon+content+hidden meta)

- OUTPUT — files are uploaded and the library is created

↓

DIGITAL LIBRARY

↓

- Create a reader from the texts that were digitized

STEP 1 — PRINTING/TYPEWRITING

INPUT — Input from step 6 [pdf(cover+extended colophon+content+hidden meta)]

- Metadata that is already in the book

- ACTION — From the digital library that was created in the first half of the workshop, the participant can choose one small portion of the book that he wants to turn into physical again (A chapter, a quote, etc.) (The cover also should be translated, author, publisher)

- [Check how long it took to print]

- A script that runs and before printing it adds our own watermark

- Print metadata (Volume GB/ File Format/ Printing Time/ Condition of the source)

- WHAT DO WE WANT TO ACHIEVE — Create a printed output that can be used as a documentation to the workshop later on.

- WHAT DO WE WANT TO ACHIEVE —Important to acknowledge what was the digital condition of the file before it turns in to the physical book (still trying to preserve what was the source). Also keeping the memory of the digital file(its file size, format printing time etc...) when it comes to reprinting it.

- OUTPUT — Printed pdf + printed metadata

↓

STEP 2 — COMPILING PHYSICAL + (One of us can compile the digital also)

- INPUT — All the printed materials

- ACTION — Collect all together the personal materials (think about a specific order on how to compile them, make a decision whether by alphabetical order, preference, format, pages, etc)

- WHAT DO WE WANT TO ACHIEVE — Individual work within the group collection and reflect on how to create a structure for it

- OUTPUT — complete reader

↓

STEP 3 — ADDING THEM TO THE SHELF

- INPUT — The reader compiled on step 2

- ACTION — Have a discussion on how could we had the book again to the shelf, where would it belong, could it still be in its old place, what is this book's place in the library now (Who are the authors?, etc)

- WHAT DO WE WANT TO ACHIEVE —

↓

PHYSICAL LIBRARY

DISCUSSION

1) Discuss event.

a) what, where, who?

- What is the event?: a place to encourage actions, using verbs (for example by Eva's definition, sharing, copying, and etc)

- A trial for what can be done through a pirate library, annotating together pirate files, produce collective actions. WHAT COLLECTIVE ACTIONS?

b) overall aim

- To have a deeper understanding, be aware of it, to do it collectively and publicly questioning anonymity

- To render what is normally invisible as visible

- To create a practical experience for audience, so that we are not communicating to audience via speeches.

- (<<steve suggests positive take on that) =: To write and read in the mode of a discussion

- Rather than making a commercial tool = experiment as an aim

- Having an experiment as an end it may translate in a material outcome. The process itself can be regarded as material.

- Forming temporary communities, by which a momentum is generated by collective action is shared, a critical mass is formed.

2) Methods of annotation

a) what technologies of annotation could be developed?

- Analog and digital annotation

- Multimedia annotation in new platforms, has annotating Music, Video, Lyrics

- Watermarking as a form of annotating authorship, how turning it around and delete the watermarks. Rather than being proprietorial, how to twist this. Use watermarking to create the ability to define provenance.

- Merge multiple annotations of the same content on a single place

- https://www.iri.centrepompidou.fr/outils/lignes-de-temps-2/?lang=en_us

- https://web.hypothes.is/

- The plurality of annotation systems, annotation through different medium, that there is not perfect system.

- Metadata [annotations in files that are apparently invisible, for the computer to read, such as SISO]

- Social network for multiple annotations / or collectively indexing [on reddit, people annotate threads by voting and downvoting; on douban (Chinese semi-social media platform on books and media, users can annotate reading remarks.] http://pzwiki.wdka.nl/mediadesign/User:Tancre/Special_Issue_9/About_categories,_tags,_keywords,_metadata_and_so_on...]

- Levels of annotation/ hierarchies?tablish rules to define the relevance of annotations. Annotation as thermometer for relevance*Recording verbal annotations coming from collective reading/watching/listening: transcribe discussions [example please]

b) consider the methods you have used to date (consider the advantages and limitations, {vis a vis what you want from this project})

- Cataloguing, indexing (such as the library system in rietveld academy, Evernote)

- Scanning, tracing, replicating, identifying, naming

c) consider the possibilities of the methods you have been introduced to as annotation tools or methods (such as, watermarking and steganography)

- The possibility of opening up the concept of "shadow" or "shadowing": zooming in the invisible layer of library to witness traces.

- exiftool, OCR, and other ways of easing the process of publishing files

- Git

- HTML

- Pad

- Bot

3) What collection of materials would be best for you to annotate?

a) what purpose does annotation serve (in your case)?

- Pedro: Rethink the role of the watermarks imposed by corporations as a form of imposing autorship and rather use them as a tool to watermark the format file as a positive tool that complements the book. Also by creating tools to delete watermarks that may show who was the source of the file, those that are visible and hidden on metadata.

How? By giving insight to its provenance, may also date the files from when they were added, where they were uploaded, from what communities do you feel part of, etc. It can increase the sense of community by adding a fake or real name to whoever uploaded it (this happens a lot in the university shadow libraries in Portugal, where some names are starting to get known but are not matched to a face) create some sort of sticker that is added in the cover OR Appending a sheet in the end or begining to the book.

b) what does it do for the reader (in your case)?

- Pedro: The ability of using watermarking that is very closely seen as a trace that is intentionaly left by publishers to trace it back to you and turn it into a tool that gives provenance to the book while creating a sense of community is the most interesting aset that I think it would bring. It creates also an interaction between the different users of a platform. Questioning also on the topic of autorship.

PERSONAL POSSIBLE WORKSHOP

"<!- A more captivating title goes here ->"

"THIS WORKSHOP BELONGS TO:"

- Start by showing different shadow libraries, while introducing briefly what different libraries have their focus on (file dumps, curation, etc...).

- Explain how to use these shadow libraries. (Can be by mirrors, direct links, etc.)

- Download different media together.

- Work around this books that were either downloaded from shadow libraries, from publishers if they are being sold for free or brought by the participants and explore them in a forensic approach.[watermarks and different types of watermarks]

- Look into different formats as epubs or pdfs and document on the different strategies used to identify a book as something that belongs to you. (Naming that if possible)

- Create a library wthin the workshop environment that is related to the guests. (Probably within a Raspberry Pi accessible by all)

- Use a script to change the books that are now "clean" and add new watermarks that may be able to form a sense of community.

- This might be a stamp that is used written on the cover, or a page that is appended to the file or even trying to use the same techniques that publishers use to critically set personal traces on your books (Might be possible with calibre)

- Think about the new traces that we could find helful leaving behind and that we would like to. As - location, date, why is it relevant, an abstract, a fake name, a real name...

- Following this structure to further continue on the workshop we could focus around this new library that has a straight relation to what people known about then experiment the tools that have been created to annotate texts, music, videos, etc. (if they exist)

AIM

- Introduce the topic of shadow libraries sharing this knowledge and how to use them in a material way.

- Create an understanding on different shadow libraries and what might be the political reasons for how they are run.

- What does it mean to be a conscient contributor to one of these libraries, provide tools to do it consciously, either when downloading or when you are uploading

- It might be interesting to have people from outside our context to understand new opinions

NEW KNOWLEDGE

- Create an awareness for parts within the file structure that might lead it back to us

- Introduce tools to remove DRMs for example.

ROLE OF ANNOTATION

- Questioning how annotation might be useful and how they also shape our way of relating to different media (how does it shape the way I read, or I listen to a music for example).

- What is the authorship dissolved when a group annotation takes place.

- Look with a critical understanding upon publishing watermarks that impose autorship and twist them as a tool that adds value within this new context of the book.

HOW WILL PEOPLE INTERFACE WITH THE PROJECT?

FURTHER ELABORATE ON

- What is the political stake?

Collective Anotation — 08-05-2019

17/04/19 — Shadow libraries Intro

ABSTRACT

Libraries like "The library" http://www.libraryqtlpitkix.onion/ and "Clockwise libraries" https://clockwise3rldkgu.onion operate within the invisible web, or hidden web are parts of the World Wide Web. Their content is not indexed by standard web engines, instead, these libraries are indexed in specific web pages just as "http://mx7rwxcountermqh.onion/". In this index, you can find an annotated list of URLs, with a small description to what each of these links is focused on.

These Libraries are not as straight forward to find, you often have to use different browsers to access them what makes them hard to come across with, making them more specific to a determined public. It is interesting how they can be seen as forming some sort of ring between themselves, also bringing a sense of community to the numerous projects found. Very few onion libraries use Calibre as a way to distribute and organize books, this is mainly because they demand the use of javascript, which is a great private vulnerability while using these browsers.

Regarding their organization, it is noticeable the way how they are curated. A lot of the projects are organized just like a folder in someone's computer. Take for example “The library”, a library that mainly focuses on sciences, with topics such as, Biology, Chemistry, Neuroscience, Physics, etc, this one looks just like a computer directory, where there is no index but the different data is stored inside folders and when you open them all the content fit in one scrolling HTML page. There are also other archives that appear to be personal libraries just as "Pokedudes Archive of Interesting and Odd Files”, a place where they organize what is described as being “a small list of ”weird or interesting files”.

QUESTIONS

- What could be the motivation to make such a library?

- Who is the target audience of this library? (exclusive channel) because this material is hard to find, these libraries don’t seem to follow the narrative of “open content for everyone”.

- Is the content of this library more exclusive that the one that you can find in the well-known (easier to access) ones?

- What makes it unique?

- If you do not have an index. How are you looking for something in this library? Is it just a process in which you came across with random material?