User:Niek Hilkmann/Graduate Research Seminar 2013/2014 - Trimester 2 II

Introduction

Few things are as fuzzy and attractive as the past. It is a concept that is never physically present, though its traces are everywhere. The most appealing bit about it might be its tangibility. One can never presently encounter in the flesh what has already transpired and that is why it is possible to make things up without anybody complaining. The only thing one has to account for within historical practice are the concrete objects that actually bore witness to past events and are now collecting fungi within the recycled air of archives and libraries. In this way, inanimate objects are the stuff historical knowledge is built upon.

Objects that are now being used as historical sources were once everyday tools and accounts. They were made and used by actual living beings with thoughts and feelings, but at one point in time they simply stopped being issued. The objects became redundant and stranded outside the field of everyday use. Even though the items and persons who used them are not seen on the streets anymore, they still have a very real place within contemporary society. Besides their economic value, historians and collectors are attracted and attached to them because of their esthetic value and the stories behind them. It is possible to project feelings and ideas upon them. Sometimes, such ideas lead to very elaborate narrative constructions, which are retold and reshaped over and over again and get new contemporary uses. Some people are critical of this approach to the past and perceive it as a denial of the future, but many more embrace it. It often occurs that old objects become part of a brand new ideology or story, either as an icon or as a brand new tool incorporating elements of the past item.

This is possible by means of reissuing which necessarily relies on past objects and sources. Nowadays, different interpretations of an endless variety of subjects can be found on the web and in digital libraries. Each one is equally represented and can be used as material for any sort of reissue. Every alternative to a conclusive past is a starting point for an alternative route that was not taken before. There are for instance certain technologies or philosophies that didn’t catch on in the time when they were proposed, but are now being used as a speculative approach to the past, present or future. As such, the past appears to be a relative subject outside the reach of a practical 'truth', since it can be bended and shaped by the ‘human mind’, which is the only true contemporary container of memory. However, something appears to get lost within these new narratives and a speculative fixation contributes to this cultural misinterpretation. The true metaphysical meaning of objects, by which I mean its particular essence, is misshapen within the process of romantic speculation and sentimental relativism.

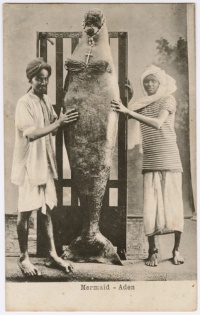

Within this thesis I will address this issue, by which I mean the object shifting through to time and being interpreted and esteemed by its projected historical character. By looking at different approaches by which historical sources are handled, some pre-digital and some that are being enforced by digital tools I hope to give a clearer definition of current discourse and curatorship as a sort of object orientated recursive romance. I am curious what kind of metaphysical estrangement is constituted by reissuing objects and how this manifests itself. Certain specified objects such as dodecaeders, disco medleys, mummies, mermaids, african fetishes, narwhal teeth and the image of the dodo will be taken as historical examples of this shifting of meaning and essence. I will delve deeper within the different metaphysical approaches to objects, for instance by means of object orientated ontology and Heideggerian phenomenology. In this way I will be able to specify what exactly gets lost within historical reissuing and what this could mean.

Chapter 1. The Endless Flight of the Dodo and the Solitaire

Lost

Few words appear so definitely grim as the word lost. Yet, this is exactly the term with which this text starts. I will use the word, proximally 150 times in the following text, so it does not hurt to know what we are talking about. The word ‘lost’ is a past sense and past particle of the verb ‘lose’ which indicates two things: 1) Something becomes ‘lost’ within an act 2) Something always got ‘lost’ in the past. Apparent as this may seem, it is quite revealing that the word indicates that something actually has to happen for something to get ‘lost’ and that this lies in the unreachable quarters of a time that has already been. A person can ‘lose’ something, but the thing is not ‘lost’ until the ‘losing’ is over. The thing stays back in the past, together with the deed of ‘losing’ while we need to carry on with our knowledge that something is ‘lost’. One does not knowingly and actively ‘lose’ something in real life unfortunately. The ‘lost’ more than often is just ‘gone’ when we arrive or maybe it even ‘vanished’. Whatever, the case, it is not there anymore, even though it was there once.

More interesting than the idea that the thing is simply not there is the fact that we actively recall it as not being there. A ‘lost object’ might not concretely be present, but it is spiritually or maybe conceptually. For instance, if we take the Rodriguez Solitaire, we are aware of it’s not being present anymore. The way we recall this is by means of historical sources. The writings Francois Leguat are testifiers of the behavior of an animal that is not living in our present world anymore. It recounts a past event. As such, historical sources can recount past events. The diary of Leguat is a first hand account of his personal feelings and emotions on the trip, yet it is also a secondary source for the existence of the rodriguez solitaire. As such the past interweaves through objects again and again. The lost has to be accounted for in secondary sources to be present. Otherwise we would just be oblivious to its existence. That which is truly not accounted for has become nihil, it is simply gone without ever getting lost.

Events are not made of solid matter, but conceptual fabrications. The battle of Waterloo took place on Sunday, the 18th of June 1815. When the fighting stopped, the battle was over. It reached our history book however, by means of narration and history writing practice. The battle had been very important for a lot of people and changed the way culture and everyday life developed. That is why it was recounted and retold. Other events, such as me scratching my head on a non-specified date in 2009 are not recounted (not even by this mere mentioned). This moment is already truly gone, I cannot remember how and when it happened and my only awareness of it is that something like that happened. There are no sources about this and there is nobody interested in the occasion, as such the event is doomed to vanish from our history,

Objects however, do not disappear so easily. They can actually sustain through several events, being made concrete, and are not made concrete by their specific relation to a time and a place. They are witnesses to a specific time and can recount something about it in ages to come. Written texts, diaries for instance, do this all the time. A diary tries to make something concrete which is actually a passing abstract time based event. Lots of objects, like paintings and photographs try to do the same thing. A concrete object can testify for the past and travel between several before falling apart. Human beings do more or less the same thing, which is why people feel so dear to objects. They are after all solid matter, just like them. Yet their minds are constantly traveling from event to event in time, making them aware and afraid of getting lost.

Present

The present is a time that actually defies characterizing. It is most easily distinguishable from the past and the future by way of it’s not being either and the debatable characteristic that one is able to ‘act’ within it. The word present has affiliation with the word ‘now’, which also means not later or earlier. Yet, when thinking about the present arises one notices several problems. Even though the past as an abstract container of mentionable past events can be very clearly defined and the future as well by means of calendars and such, this is not the case with the present. Sometimes it’s just like events just fly though this moment to arrive at the other destination. Even though the present is a tough cookie to define we will look at it with the concept of ‘losing’ again in our mind.

In the previous paragraph I suggested that the word ‘lost’ suggested that an act of losing would be necessary for something to become lost in the future, where it would in turn lie in the past (see picture). As you see in the attached picture one has to actively lose something for it to become lost. This proposes a couple of problems though. In the present, one cannot have lost the thing one is ‘losing’, which means one loses something by making it shift to the past to make it lost in the future. This would suggest a sort of time traveling. The future however never arrives according to this logic, because one cannot define the present in the same way as a past event in which it already happened. This paradox all the more proves the inadequateness of linguistics when it comes to thinking about time, objects and space.

All mind games aside, the true problem with this idea of ‘losing’ is that it suggests that objects get actualized by being subject to an action, if not ‘losing’ than another deed. This means that something that is being ‘used’ in the present tense is something actual. To be more concrete, that something that is being put into ‘action’, more or less like a tool, and being part of a time-based event, is an actual object, while a passive object is part of the past. This suggests that the ‘lost’ or ‘redundant’ object’ at one point stops being ‘used’ which makes it a ‘past’ object. The strange thing about this is that passive objects, meaning past objects actually recount the past in the present, making it an active participant of another time. What I would like to propose is to clearly define these two characteristics of the object, the ‘present’ one that gets shifted to the ‘past’ and the ‘past’ one that gets shifted to the ‘present’ in the next chapter.

Reissue

So far we have focussed upon the linguistic metaphysical definition of certain times in relation to the meaning they have for concrete objects. In this paragraph I would like to consider the concept of issuing and reissuing to highlight another side of this matter. When we consider objects as being either ‘active’ or ‘passive’ we are condemning them to both time-based and matter-based constraints, while the actualization of objects is actually a duality that becomes concrete in its relation to mankind. Let’s propose the most basic of all human tools: the axe. We take an example from the Paleolithic age and consider the following. 1) The axe was used during the Paleolithic age 2) This age lies in the past 3) It is not being used as an axe anymore. I highlighted the part ‘as an axe’ for a very specific reason. When we consider the axe as a representative of the Paleolithic age we do this by considering it a tool with a specific purpose that illustrates its usage. By not being used with this idea in mind the object has become redundant, much like its owners and builders. However, this is not the entire matter.

First off, the axe has more purposes, as an historical object it has shifted through many more hands that were not interested in cutting meat. The axe can be put into a display in the museum and become a narrator of a certain time, as I already proposed. Bu the axe can also live up to a certain economic value at an auction and become a sort of currency. This is already a way of reissuing it within a contemporary framework, making it an active participant again, but divided from it’s past meaning which is certainly ‘lost’ in the process. Now consider the tourist industry that makes new hand axes to sell as souvenirs. These are in a sense authentic hand axes, one only needs to cut something up with it to make them active again, but furthermore they are contemporary souvenirs with their own meaning.

A souvenir is a personal remembrance, a very concrete manifestation of a specific time based event, like visiting a Paleolithic cave for instance. This personal aspect is able to give an object almost any meaning and relation you like. The axe becomes something completely else than might ever have been intended. This is up to you. From an historical viewpoint this puts in question the matter of authenticity. All kitsch and forging is at once an authentic form of kitsch and forging. A lighter in the form of a hand axe is actually a nifty resurgence of primitive design. As an historic object it’s a concrete reissuing of an historic object that puts the original in a perspective, yet also disfigures it. In our next chapter we will consider what is actually disfigured, according to whom, what gets lost in the process and what we win by reissuing objects and making them shift through different times.

Chapter 2. The Greatest Recursive Disco Medley In The World

Give Life Back To Music

It seems already quite some time ago that Simon Reynolds published his overtly discussed book ‘Retromania’ in 2011. Much has been made of this analysis of popular music in the three years since it’s release and it has to be said that its stream of thought was appropriated and accepted by music journalists with an enthusiasm that they rarely exhibit for the records they review. In ‘Retromania’ Reynolds tries to illustrate the idea that popular music has become a self-referential medium, obsessed with its own history and not moving forwards anymore. With a touch of melancholic drama he recalls the days when he felt music still held promises for the future and he wonders if contemporary music will ever bring him back that feeling again.

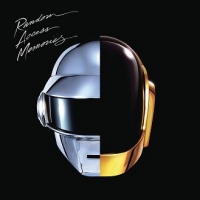

Only two years after Reynolds published this stream of thought Daft Punk released an album that almost seemed to be tailor made to illustrate his ideas. The album was fittingly called ‘Random Access Memories’ and the title of the first song showed the almost impossible high goal they were aiming for: ‘Give Life Back To Music’. They call the listener to arms by crooning the following lyrics in the opening song:

Let the music in tonight

Just turn on the music

Let the music of your life

Give life back to music

There are two kinds of ‘music’ present in this short stanza; Actual music, presumably blasting through some sort of degenerate stereo set and ‘the music of your life’ which appears to be vague metaphoric fodder for whoever wants to read more into the lyrics than there actually is. Whatever the case may be, this 'music of your life' appears to be the thing that brings the contemporary music you listen to life. Without this, it is devoid of meaning. Perhaps Daft Punk merely try to make a general assumption that life should be lived, but the album seems to take the lyrics quite literal. The original makers of the music of our lives, the 'oldies and goldies', are actually present on 'Random Access Memories' and collaborate with Daft Punk. Giorgio Moroder, Pharrell and Niles Rodgers all got phoned in to show their skills on the record. As such, the music of the past is present on the album to give life back to contemporary music and as such, contemporary life and emotions. Daft Punk use a pre-existing musical framework to create ‘new’ music that fits our day and age by actualizing past music.

Back To Music

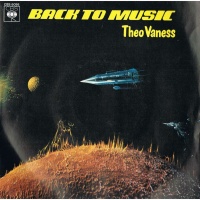

The idea of borrowing from the past to create something new is by no means particularly fresh. In fact, there are many predecessors to the retro obsessed age that Reynolds describes, even in the 'futuristic' years he writes so nostalgically about. There are minor differences within the approach to historical material between ages, but the contemporary quality of music is something that was always defined by technology and industry. Thus, 'retromania' was always present as a commercial mechanism, only differently defined. A very obvious example of this is the bootleg disco culture of the late 70s and early 80s. In 1978 a Dutch popstar called Theo Vaness decided to release his first disco record. It was called ‘Back To Music’ and turned out to be of dark horse in the scene. The record starts with machines rattling and beeping in the background while a voice declares:

This is the year 2501.

Our world is no longer a place where you can dream of the future.

Only of the past.

We use our time machine now and then to go back to nature, back to music.

After this a disco beat starts and a countdown takes place. Year after year passes, until the listener reach 1978, the year 'Back To Music' was cut. The journey through time is far from over, as Theo Vaness starts singing the Beatles' ‘Yesterday’ and a medley of Beatles songs and popular hits from the 50s, 60s en 70s commences. After a couple of minutes the song reaches a sort of climax and the listener is safely transported back to 2501, the year where there is no future and people go back in time to experience music. This travel through time can be seen as a mere piece of science fiction, but Vaness' thoughts on how music might be perceived in the future isn't so far off from what Reynolds speculates on and what Daft Punk illustrates on 'Random Access Memories'.

The actual music that accompanies Vaness' story is pretty particular however. Daft Punk made a meta-album with ‘classic’ artists in a contemporary environment. By appropriating popular melodies and styles they attempted to make a 'new' historical record. Theo Vaness made a futuristic disco record about a speculative future. The musical past he appropriates is conformed to a contemporary disco style, which was a standard at the time. In this way it speculated on being a classic record, instead of trying to recreate the sound of the past, like Daft Punk attempts.

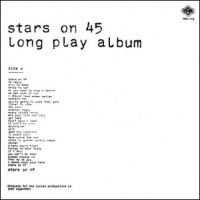

Stars On 45

In the summer of 1979 Willem van Kooten, managing director of Red Bullet Productions by chance heard a disco bootleg record by Passion called ‘Let’s Do It In The 80s Great Hits’ that featured a sound byte of Shocking Blues’ Venus. Van Kooten owned the copyrights to this song, but he was not paid any money for this bootleg release. As a sort of response he decided to bootleg the bootleg and got one Jaap Eggermont to produce the first record of what later would be known as the 'Stars On 45' series. These bootleg disco records feature soundalikes who sing bit parts of popular songs and artists. For instance, 'the greatest rock and roll band of the world' features 17 Rolling Stones songs accompanied by a relentless disco drumbeat that goes on and on and on. The beat normalizes and unifies the songs and takes them out of their context. Its a rather brain-numbing affair.

These records were by no means critical successes, but made a lot of money. The lengths the producers went through to make them sound ‘alike’ are quite extravagant compared to todays standards. There is definitely some sort of art involved in making inconspicuous covers, but with current sampling technology this whole process has become so easy that sounding alike is not such an interesting feat anymore. This makes the Stars on 45 particularly anonymous nowadays. While Vaness is actually still in the center of his medleys by singing the songs himself, the artists on the 'Stars on 45' releases pose as mere sound effects. It could be said that this commercial, mindless appropriation of a musical past is the true precedent of shuffle culture and spotify and youtube music consumerism. As opposed to Vaness there's no personal flavor involved in traveling back to musical times. The past is relentlessly normalized, decontextualized and stripped of any meaning. As such, the music becomes the container of everything we want to, much like 'the music of our life' Daft Punk sing about, an empty shell for our personal fetishes. The 'Stars on 45' are no longer necessary with digital shuffle players around and become a redundant sort of reference, because they lack personal flavor. One could just as easily play the original.

Daft Punk are part of a commercial apparatus and their approach to music isn’t unlike that of the stars on 45. Instead of merely trying to sound like commercial records from the past, they actually invite the very people over who made these. In this way it produces a sort of recursive record industry. The guest appearance of Paul Williams in ‘Touch’ doubles as an ode to ‘Phantom Of the Paradise’, a 1974 satirical movie directed by Brian Da Palma in which this industry is portrayed as a recursive beast that appropriates past styles again and again to gain money and success. In the movie is run by monsters who can’t stand getting old. Daft Punk would have fit right into the picture and ‘Random Acces Memory’ might function as a sort of alternative soundtrack to that. Paul Williams was always part of the recursive smoke & mirrors industry that they try to bring back to life. Apparently they hope to bring back these mirrors themselves instead of their effects. The way this is established by industry and technology is by no means a new thing and Simon Reynolds merely seems to have struck a contemporary chord in linking this to a specific type of music that popped up on the market when he wrote his book. Theo Vaness envisioned a disco utopia that was destroyed when disco backlash peeped around the corner. In the end he was a thing of his time, much like Daft Punk and Simon Reynolds will be.

Chapter 3. Utopian Anthropomorphism

Conclusion

Literature

Dodo

- The Dodo and the Solitaire: A Natural History, Joylon C. Parish, 2013.

- The Dodo: From Extinction to Icon, Erroll Fuller, 2003.

- The Song of the Dodo, David Quammen, 1997.

- Return of the Crazy Bird: The Sad, Strange Tale of the Dodo, 2003.

- The dodo and its kindred or, The history, affinities, and osteology of the dodo, solitaire, and other extinct birds of the islands Mauritius, Rodriguez and Bourbon, H. E. Strickland and A.G. Melville, 1848.

- Alice In Wonderland, Lewis Carroll, 1865.

- Dodos Are Forever, Dick King-Smith, 1989.

Media

- Retromania, Simon Reynolds, 2011.

- Imaginary Futures, Richard Barbrook, 2005.

- Evil Media, Matthew Fuller and Andrew Goffey, 2012.

- Anti-Media: Ephemera On Speculative Arts, Florian Cramer, 2013.

- Remediation: Understanding New Media, Jay David Bolter and Richard Grusin, 2000.

- Tool-Being: Heidegger and the Metaphysics of Objects, Graham Harman, 2002.

- Guerilla Metaphysics: Phenomenology and the Carpentry of Things, Graham Harman, 2005.

- The Democracy of Objects, Levi Bryant, 2011.

- Alien Phenomenology, or What It's Like to Be a Thing, Ian Bogost, 2012.

- Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things, Jane Bennett, 2009.

- The Media Equation: How People Treat Computers, Television, and New Media Like Real People and Places, B. Reeves, B and C. Nass, 1996.

- Machines and mindlessness: Social responses to computers, C. Nass, C and Y. Moon, 2000.

- You Are Not a Gadget: A Manifesto, Jaron Lanier, 2011.

Furthermore

- The Follies of Science at the Court of Rudolph II, 1576-1612, Henry Carrington Bolton, 1904.

- The Future Of Nostalgia, Svetlana Boym, 2002.

- When Elephants Weep: The Emotional Lives of Animals, Jeffrey Moussaieff Masson, 1996.

- The Complete Hans Christian Andersen Fairy Tales, Hans Christian Andersen, 1981.

- Sein Und Zeit, Martin Heidegger, 1927.

- The Brave Little Toaster from Print to Film: Obsolescent Appliances and Capitalist Allegories, Margaret D. Stetz, Opticon 1826, 14: 21-26, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/opt.aj, 2012.

- The Brave Little Toaster, Thomas M. Disch, 1980.