User:Menno Harder/project proposal

Introduction

I would like to open a new social space within my own neighbourhood. Through different kinds of research, both in an artistic and collaborative way, but also with a theoretical approach I want to create an archive of work surrounding my own place within this neighbourhood and anticipate on the wide range of possibilities that such a space could bring to its surroundings. Ideally this place will be an environment where we can have workshops, talks, music and show movies but also have the opportunity to invite people from the neighbourhood to come by for a cheap weekly dinner, take free items from the give–away shop and have a place to quietly read the abundance of books that will be available for everyone.

I would like to carefully plan and create a possible structure for a such place. What can its appearance be, its meaning within the context of this area in Rotterdam? How does it relate to my personal opinions about the city, and the current cultural climate within Rotterdam, and, even more important, how do I present this space to the people that are passing by or are living near it. Some of these questions will be answered while gathering information and researching the subject itself. I can imagine that the opening–exhibition of this space could be the visualisation of my own research and thoughts towards living in this neighbourhood, what we can and what we can’t do. As the Middelland neighbourhood consists of quite a few different area’s, both in physical appearance (its architecture and street planning) and in its social structure: it is a very multicultural part of Rotterdam, quite segregated and has seen some huge gentrification in certain parts the past years this is certainly an aspect that I could explore and visualise through the use of graphic design.

Relation to previous practice

Forming new idea’s and starting a new project relies on the experience I have had with past projects. A new project is built while still dealing with the thoughts and concepts of a just finished project. Looking back on works I have done in later years, I identify a certain way of working and initiating projects. A work usually comes forth out of an exploration of the area visited (this can be exploring the place while actually being there), or exploring it by listening to stories or reading about it either on the web or in a written document. Examples of these are: Am Kotti (2011), Plas Nasyonal (2011), Atlas of Experience (2011) and Remembering Tuzla & Sarajevo (2013), I have included a short description for each of these projects. Usually the mere visualisation and translation of such an area can be a work in itself (objective journalism, documentation), but identifying the conflicts that happen within this area and commenting on them gives the work a personal and subjective layer, making the work critical towards the topic it is discussing. This project will most certainly be a combination of these two elements, in one way it is a celebration of the neighbourhood, what it was, what it is and what it can become. But on the other side it is a critical reflection upon its history and current state. I understand that this is also a personal opinion, and that I do not share these opinions with everyone.

Please click the images for a clearer view:

It is important to work for a certain kind of audience, who am I making this project for? Why am I creating an archive of several neighbourhood projects? What do I see happening in Middelland right now, and how can I be sure that this additional space integrates within the already existing shops, bars, offices, houses and in a more abstract way the atmosphere (or, feel) of this location. While it seems important to actively DO something, I have to realise that my intentions are not necessarily shared by everyone. So the reasoning behind my intentions should be clear, and should take in great consideration what the actual benefits towards the neighbourhood of this supposed space will be. Some of these questions are difficult to answer right now as much of them will be answered while initiating the different research-projects. To have a clear image of what the neighbourhood actually is and what it consists of is nearly impossible. It is a space that is constantly changing and re–inventing itself. This can be felt throughout the neighbourhood but especially on the central street, where most of the shops and bars etc. are located which results in more contact between humans. However, through the use of archived material you can actually have a guess at who is situated here at a certain time and how the area is slowly changing. One of the projects I am working on right now that will give some insight in this is the collecting and archiving of imagery that have been shot in Middelland the past 100 years (some of the pictures can be seen throughout the text), while another collaborative project I am working on together with Vincent de Jong involves a route we have walked through the streets that I consider my case subject: the streets around Middellandplein. During the walk we looked at the neighbourhood and carefully documented what makes it so unique by recording and abstracting it's architecture.

Research trajectory

The creation of an autonomous cultural space has of course been done before and is still been done in cities throughout the world. For example, there are many active squatting groups in several Dutch cities that are reclaiming certain empty spaces and turning these into cultural centres, without the help of any municipality or subsidies from third parties. The reasoning behind taking an empty space can be for various reasons, these could be socially engaged or have a political meaning, usually a reflection upon the climate in the actual city. In my case, the decline of alternative culture within Rotterdam has been a starting point for this project. Apart from the squatting community there are of course also initiatives done by various groups that support the usage of empty space within their own surroundings as a way to re–invent urban space. I understand that this project is also a very personal matter, as I see many empty spaces in my own neighbourhood, it feels like the right moment to do something myself. Apart from claiming the actual space to perform all these activities I have to take into account the effectivity of my plans. The importance of the audience is not to be underestimated. Will this centre be an artistic environment with mostly young people or will it be suited for any kind of visitor, even those without interest in for example the current exhibition. I have to find a way to make these different groups work together, so that it can be a place for everyone. I also wonder about the Rotterdam municipality, and how they plan the neighbourhood of Middelland and especially the West-Kruiskade area and 1e and 2e Middellandstraat. As various stores are popping up everywhere, and small scale business seems to flourish in these streets, how open and willing would they be for a proposal like this? And while there are several cases of successful openings, there have also been numerous spaces that had to close down due to bankruptcy and so on. An ideal situation would be a space that could survive every month by breaking even, living of of small donations and the work of volunteers.

As a starting point of my research exploring and documenting the neighbourhood in several ways (through interviews, photographs, extracting and recognizing certain specific elements from the streets, visualizing and abstracting its street life, recording the ‘sound’ of the neighbourhood) will hopefully provide me with more knowledge about the situation, and in it’s turn provide an explanation for my cause. The creation and afterwards evaluation of what I see as neighbourhood projects will give me more information and reasoning as to why I want to do this, and how I can do it.

Some of the projects I will be doing this year involve the help of my friends and colleagues, all of them who have a certain idea about coming to this place and experiencing the atmosphere here. I will work closely together with them and create idea's and eventually publish these. Some examples of early work regarding this graduation project are: Huis Middelpunt with Charlotte Brand, which is a project that takes into great consideration our place within this neighbourhood. How do we view the street from our house, how much of the outside world we can actually notice while being safely inside our own house? Interviews about rain with Malou Kortleve, 4 interviews were conducted with 4 inhabitants of Middelland. Questions range from: "What do you do when it rains outside?" to "What do you think about the neighbourhood you live in?". Mapping the empty advertisements in the streets and creating a guerilla–style advertisement for the upcoming space with Yin Yin Wong and the creation of a neighbourhood bulletin with Vincent de Jong.

The accompanying website for Vragen over regen (Interviews about rain): www.mennoharder.nl/Vragenoverregen

Or take a look at some of the moving collages made for 'Huis Middelpunt': www.mennoharder.nl/Huismiddelpunt

Whilst creating this archive of information I would like to create awareness of my idea's and share these with as many people as possible. In the end, it is important that my cause and intentions will be known by not only my personal surroundings, but that they also change the psychological space on the street itself. For example: There will be a festival/exhibition opening in the beginning of 2014, to already take the step from working behind a computer to bringing our idea's and identity on the street. When I introduce announcements for an event that might happen involving the creation of this space, then already it starts to become real, preparing the neighbourhood for a future opening.

Outcome

Eventually the various different projects that I have done throughout the year will be revealed. Presenting all the material that has been collected and created through collaborative work and research of the subject. I see this eventual outcome as a library that explains the reasoning behind the projects, it shows a personal narrative and timeline that binds all the projects together. The viewer is able to see clearly all the research that has been done. This library should be located within the neighbourhood it researches, so to return the information to the local community. Obviously, the acquired space would be the most suitable place of presenting this. So while I am initiating all sorts of projects throughout this year there is also the struggle of obtaining the space, the research into previously done similar projects, the planning, talking and meetings that I have that are practical steps towards acquiring it. These steps should be carefully documented as they provide the story behind this whole undertaking. They can give a interesting insight in what works well and what does not and can be very helpful in writing my thesis.

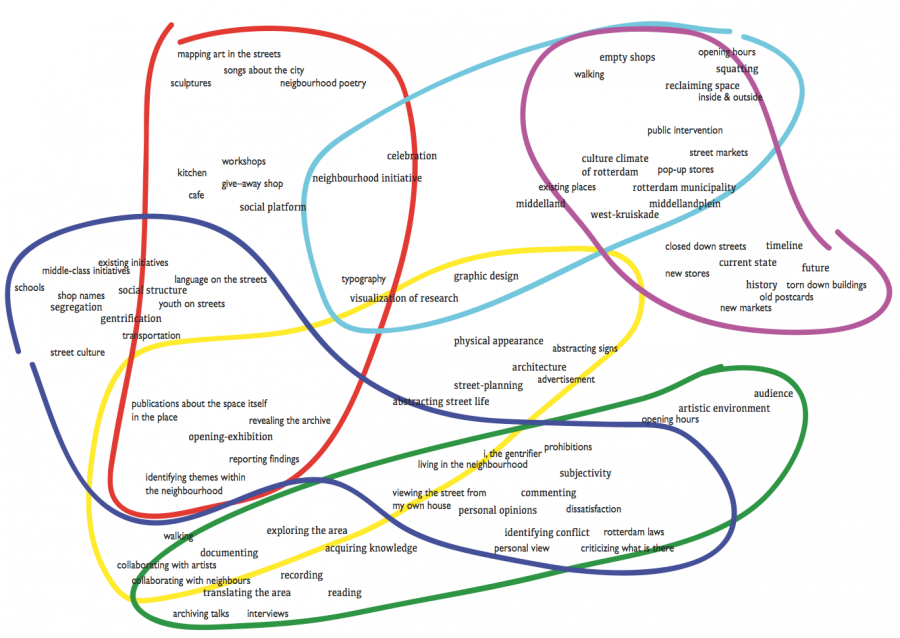

Mindmap

Bibliography

What we Made Conversations on Art and Social Cooperation, Tom Finkelpearl

In What We Made, Tom Finkelpearl examines the activist, participatory, coauthored aesthetic experiences being created in contemporary art. He suggests social cooperation as a meaningful way to think about this work and provides a framework for understanding its emergence and acceptance. In a series of fifteen conversations, artists comment on their experiences working cooperatively, joined at times by colleagues from related fields, including social policy, architecture, art history, urban planning, and new media. Issues discussed include the experiences of working in public and of working with museums and libraries, opportunities for social change, the lines between education and art, spirituality, collaborative opportunities made available by new media, and the elusive criteria for evaluating cooperative art.

Living as Form, Nato Thompson

Over the past twenty years, an abundance of art forms have emerged that use aesthetics to affect social dynamics. These works are often produced by collectives or come out of a community context; they emphasize participation, dialogue, and action, and appear in situations ranging from theater to activism to urban planning to visual art to health care. Engaged with the texture of living, these art works often blur the line between art and life. This book offers the first global portrait of a complex and exciting mode of cultural production—one that has virtually redefined contemporary art practice.

Artificial Hells, Claire Bishop

Since the 1990s, critics and curators have broadly accepted the notion that participatory art is the ultimate political art: that by encouraging an audience to take part an artist can promote new emancipatory social relations. Around the world, the champions of this form of expression are numerous, ranging from art historians such as Grant Kester, curators such as Nicolas Bourriaud and Nato Thompson, to performance theorists such as Shannon Jackson.

Artificial Hells is the first historical and theoretical overview of socially engaged participatory art, known in the US as “social practice.” Claire Bishop follows the trajectory of twentieth-century art and examines key moments in the development of a participatory aesthetic. This itinerary takes in Futurism and Dada; the Situationist International; Happenings in Eastern Europe, Argentina and Paris; the 1970s Community Arts Movement; and the Artists Placement Group. It concludes with a discussion of long-term educational projects by contemporary artists such as Thomas Hirschhorn, Tania Bruguera, Paweł Althamer and Paul Chan.

The One and the Many, Grant Kester

As artists increasingly produce work on international sites in conjunction with local populations, art historians seek to model these new practices and assess their conceptual and political implications. In his previous book, Conversation Pieces: Community and Communication in Modern Art, Grant Kester historicized the shift away from art as object-making to art as an open-ended form of exchange, which he characterized as “dialogical practice,” wherein art “unfolds through a process of performative interaction.” In his most recent book, The One and the Many: Contemporary Collaborative Art in a Global Context, Kester expands upon his definition of “dialogical practice” to advocate for collaborative, politically-engaged artwork that blurs the line between community activism and artistic production.

Conversation Pieces, Grant Kester

As artists increasingly produce work on international sites in conjunction with local populations, art historians seek to model these new practices and assess their conceptual and political implications. In his previous book, Conversation Pieces: Community and Communication in Modern Art, Grant Kester historicized the shift away from art as object-making to art as an open-ended form of exchange, which he characterized as “dialogical practice,” wherein art “unfolds through a process of performative interaction.” In his most recent book, The One and the Many: Contemporary Collaborative Art in a Global Context, Kester expands upon his definition of “dialogical practice” to advocate for collaborative, politically-engaged artwork that blurs the line between community activism and artistic production.

Art Scenes, the Social Scripts of the Art World, Pablo Helguera

Starting in the mid-1990s, either through performance, drawing, music, theater or literary fiction, the work of Pablo Helguera has extensively addressed the social dynamics of the contemporary art world. This book brings together Helguera’s research on the subject in essay form, aiming to contribute to the neglected area of the sociology of contemporary art.

In this provocative new book, Helguera argues that contemporary art makes us perform self-conscious or instinctive interpretive acts; and that the construction of value in artworks is determined less by the objects themselves—and by extension, by the art market—than by the nature of our interpretive performances, having a trickle-down effect on practically every aspect of art in society. Bringing together perspectives from sociology, education and art theory, Art Scenes aims to contribute to the inauguration of a new field described by Helguera as “Art World Studies.”

Social Works, Performing Art Supporting Publics, Shannon Jackson

Shannon Jackson’s Social Works embraces a range of late-twentieth and early twenty-first century visual and theatrical works of Europe and the Americas variously categorized as performance ethnography, site-specific art, documentary theater, public art, and post-dramatic theatre. Like Amelia Jones, Jane Blocker, and Rebecca Schneider, Jackson—Professor of Rhetoric and Theater, Dance and Performance Studies at University of California, Berkeley—takes on a capacious set of projects in theaters, on streets, and in galleries to offer “critical traction” to a field of expanded art practices vexed by medium-specific critical approaches (14). She traverses genealogies of visual and theatre studies in order to dislodge the perceptual and methodological patterns that tend to overlook the interdependencies between art and social systems. Rather than looking at how art does something to or for a public, Jackson devotes attention to works that provoke a sense of the blurred lines between the artist and the social.

Dark Matter, Art and Politics in the Age of Enterprise Culture, Gregory Sholette

Art is big business, with some artists able to command huge sums of money for their works, while the vast majority are ignored or dismissed by critics. This book shows that these marginalised artists, the 'dark matter' of the art world, are essential to the survival of the mainstream and that they frequently organize in opposition to it.

Gregory Sholette, a politically engaged artist, argues that imagination and creativity in the art world originate thrive in the non-commercial sector shut off from prestigious galleries and champagne receptions. This broader creative culture feeds the mainstream with new forms and styles that can be commodified and used to sustain the few artists admitted into the elite.