User:Mathijs van Oosterhoudt/projectprop2

Camera Induco

Introduction

'To behold, use or perceive any extension of ourselves in technological forms is necessarily to embrace it. By continuously embracing technologies, we relate ourselves to them as servo-mechanisms.' - Marshall Mcluhan

'We become what we behold. We shape our tools, and thereafter our tools shape us.' - John M. Culkin

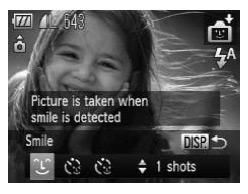

[Please click on photos to enlarge them]

Put shortly: My goal is to create a camera (or set of cameras) which is designed with the idea of making visible to some degree the ways in which it is shaping its user, the inherent issues surrounding the camera and who controls the mode of production that governs and governed these tools throughout its evolution.

A tool is a specific application of technology, created to solve problems. Technology constantly influences how we view the world around us, and by logical consequence (The tool is part of technology after all), so does the tool; That which allows us to (in an ideal world) influence the shaping of technology directly, rather than indirectly influencing us. We hold the tool, we use the tool, we determine how it is used, etcetera.

However, just Like with technology, it is not that easy and it becomes important to question who controls the creation of tools, as often the user of the tool is not the same as the creator, And if so, the creation of tools still requires tools and is influenced by his or her's view and understanding on technology (i.e. if one would make a measuring device, it would most likely be modeled after an already existing one, rather than trying to invent one's own technique of measuring). Small changes in tools influence us in ways unimaginable, and while problem-solving through the creation of tools might sound ideal, one also has to understand that commercial tools might not only be created to solve our problems, but perhaps largely their (The creators, the shapers of tools) problems.

Tools solve problems, but tools also restrain. Crudely put: By doing one thing, it might not be doing the other thing. The specifics of the tool is one of many decisions, many restraints. We pick our tools (Perhaps unconsciously) on which restraints we prefer or think we require. These restraints shape the outcome of the work we as users attempt to create with the tool, but also influences the way we perceive the tool (And through that, technology and society). However, creators (of tools) don't actively shape tools to what they want them to do to the user in mind, but rather by what they think they want them to do for the user (Langdon, Technology as Forms of Life).

Technology is not something that influences us solely on its own, but rather its use, both directly as well its use in context (socially and culturally) is what influences us (McLuhan, Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man). How a tool is shaped or created greatly influences its possible use, to the point where it becomes important that users are able to shape the tool as is required for their needs. This appropriation might seem quite commonplace with the blooming maker culture nowadays, but do realize that appropriation of technology comes with the understanding of technology. I understand a book, I understand its shape, hence my ability to use it to level out that one odd leg on my table. Appropriating more complex technology however becomes harder as it evolves with time. Where one might understand a pinhole camera (Inherently just a black box with a hole on the front), one can nowadays not easily understand the mechanics of a digital camera without in-depth studies. This prevents us from appropriation, therefor giving power to its creator - those who control the means of production. Even more so, many tools and machines are build with blockades in mind, anti-features that limit us from getting the most out of it (Sometimes quite directly through planned obsolescence), that block access to certain features or certain methods of use.

A last question to ponder is that of the use of the tool versus that which it creates. The user often sees tools as a means of getting his or her result, but whilst both the result and the journey matter, to what degree is the actual usage of the tool of influence rather than its end result (or possibilities)? Where a painting from Pollock references the act of painting itself, the end goal of any tool in some way, shape or form will reference the tool (And thereby technology) itself. How does the tool relate and play a role to the now common phrase The Medium is the Message? How can we apply these thoughts to for example the near-instantaneous result of a camera? How much is it the camera that shapes us as our tool compared to that of the photo shaping us as the end-result of the process?

Relation to previous practice

The themes discussed in the previous chapter relate to an article I have recently written about the push button. The push button holds a special place in history, as it is the first method of interacting with machines which completely hides its inner mechanisms and distances the motion of using the button (Pushing) from what the machine actually does (Opposite to, for example, a lever). A retrospective article looking back on the history of the button (In both the button itself as well as its marketing), why things became the way they are and how those specifics are used or exploited. The goal is bringing these design choices and their effects to light and make it possible to use these effects to our advantage, rather than as an exploitation as is often the case.

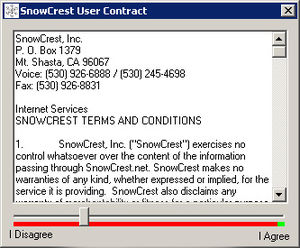

This exploitation of obfuscation (Hiding complex choices between a binary choice) is displayed in the prototype on the left. In this case, normally your options would be two buttons: One to agree, one to disagree. It is a binary choice, on or off. This may seem like a neutral and objective 50/50 choice, but by changing the technology or tool used (In this case the push button) to one which eliminates the specific exploited restraint of the other, one can expose how these restraints are used.

By changing the binary push button to a slider going from left to right, quite quickly we realize that no matter where you may find yourself from 0 to 100 (The former being disagree, the latter agree), all but the last choice (Fully agree) would actually result in you not agreeing.

Project wise it relates to such projects as the GeoCam, a phone app which instead of taking new photographs, searches for relevant photographs to your location and camera orientation, allowing the recycle of existing imagery without need for new ones. It reflects on what we require from our camera and what we expect it to do, whilst questioning the need of the users requirements (And the abundance of imagery).

Another, The Local Web app relates in that it makes clear how we've started to think differently as influenced by every day technology, trying to show how we've taken the wideness of the web for granted. By only being able to access websites that are stored in your local vicinity, one is confronted with the inability to access the 'world wide' part of the web. At the same time, it displays the physicality of the internet which is often obfuscated and hidden behind the 'magical' browser. How data is stored and more importantly where impact the contents of a website through various ways, for example, politically (The law of the hosting country applies). By forcing a person to (in theory) walk to Russia to access a website it becomes unavoidably visible that one enters their legal zone.

Relation to a larger context

The project takes a looks at such themes as the social construction of technology and techno-determinism in relation to the camera.

It tackles similar themes in a different way to the work of artists like Aram Bartholl, who in a project like Map places a google maps marker in what Google Maps defines the center of the city, thereby not only showing the influence of technology of us by shifting the icon from the digital to the real, but also bringing to question who they are to decide what is the center of a city and who actually has control here.

Whilst we also influence how technology influences us in return by how we use technology, the restraints put on how we have access to it (Through the means of tools and machines) is controlled by those who control the means of production, such restraints inherently influence our possible uses of said technology and thereby, logically, our influence on its course.

In a more physical way it relates to projects like Matt Richardson's The Descriptive Camera, a camera which doesn't take pictures but prints a small piece of paper describing what was seen through the viewfinder, playing with the perception of the user (Possibly expecting an actual camera) and making people a very visible part of the mechanism (The descriptions are written through the use of Amazon's mechanical Turk).

On the theoretical side it relates most to earlier referenced works (Marshall McLuhan - Understanding Media and Langdon Winner, Philosophy of Technology) as well as that of John Tagg, The Burden of Representation (In how it questions who has control and how the effects of that on the photograph in turn influences us).

Thesis intention

By thoroughly examining the different ways of how cameras have evolved and have been altered and how they have influenced us throughout the years, both now and how we look back at the past (Through photographs) and how the social structures have influenced that development, I hope to directly be able to apply such changes and information in creating my own project. It will delve into the social and cultural constructions that influenced the shaping of the camera to what it is today and how that in turn effects us.

By focusing on the camera instead of the tool in general I want to be able to show more concretely this influence with examples, whilst making a text that is still applicable to the use and creation of tools in general rather than solely the camera, but also offer something more directed and showing its direct influence.

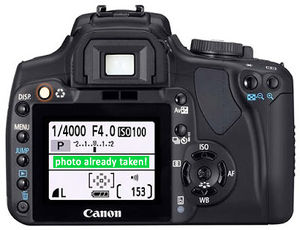

The camera is interesting for many reasons. Of course there is it's undeniable impact on culture and society, but also the way the camera is multifaceted, by both being a consumer tool, an artistic tool and a scientific tool for such sciences as ethnography. While it has these many uses, often the same cameras are used for each intention, influencing each intention (And result) differently.

In the past years I have accumulated a large knowledge in cameras, their history, evolution and workings.

Practical steps

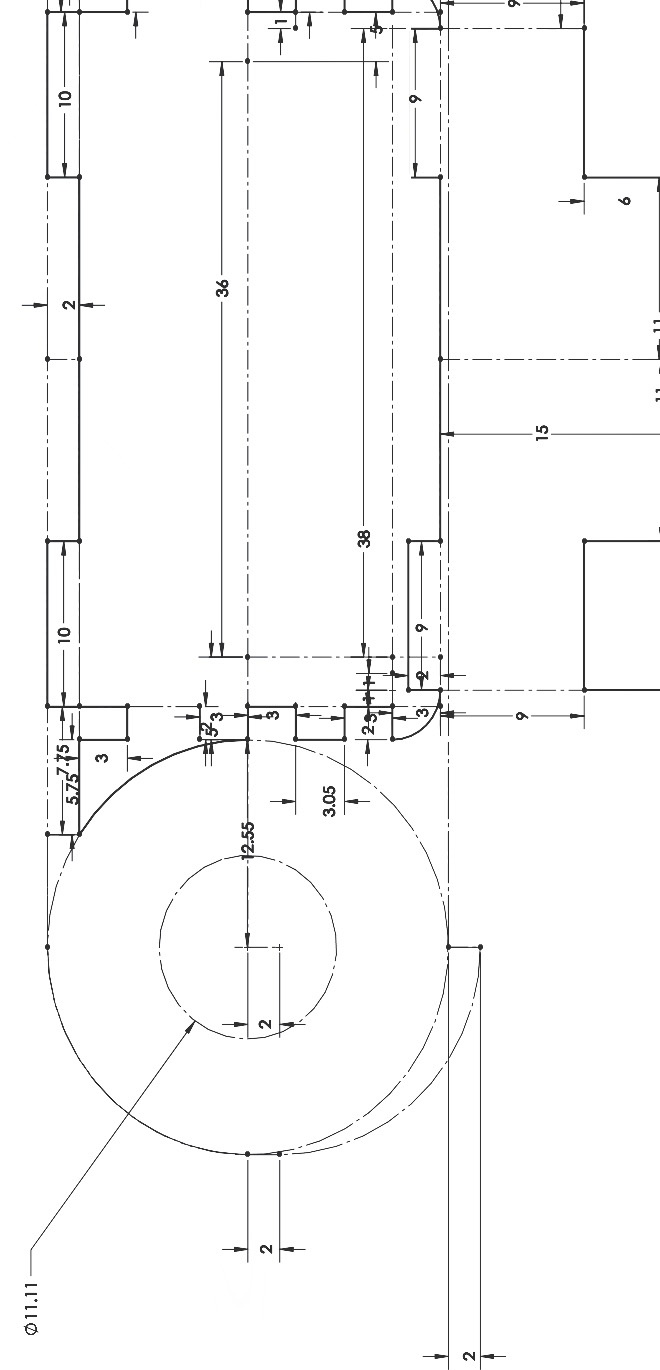

Researching the history of changes and the evolution of the camera, I'll try to understand how these changes take shape and who benefits from these. By exaggerating, changing or adapting these same techniques as have influenced us in the past, I hope to create new cameras that can bring this to light.

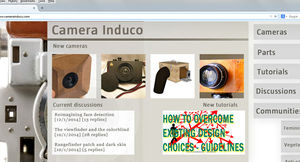

A secondary goal is to make these cameras and technologies freely available to others, allowing other people to create projects and cameras with them. By making these technologies open, I hope to make appropriation of cameras more accessible. Many of the current mechanics used might seem daunting, but when broken down to their basis are surprisingly basic.

If I would want to spread the ability to let others further the ability to make cameras, it would require a platform for people to discuss and share designs. While a lot of parts seem daunting to create, if they're freely available (Take a shutter), it could speed up the process of the DIY Camera community in multiple ways. What is interesting about this is that the people who have had control over the development over the camera are those with power and money, but cheap ways of producing one's own camera could give for example minorities the ability to make cameras to what they desire out of one.

While I as a white male in the west am not part of any minorities, it becomes hard to envision such a camera. The only camera that would make sense for me to develop in this sense would be one that acknowledges my own privilege.

Adapting or marking the original tool is another possible way of making its inherent flaws visible. In this case, I've taken the coin as the tool (If a tool is a method of interacting with technology, surely the coin would be the way to interact with economy). A sticker sheet allows anyone to easily mark their own coins, or for me to do so and spread them once more.

The stickers list the actual cost of making the coin, which visualizes an interesting problem: 1 cent and 2 cent coins cost more to make than what they say they are worth, making one question why one would mark a coin worth as 1.67 cents as 1 cent. Ireland has come out about this problem and said that they've lost an approximation of 4.7 million euros simply producing 1 and 2 cent coins, as one loses money for every 1 and 2 cent coin made.

Another possible way is explored through the use of a model kits. This 1/1 Caliper is a model kit of a caliper, which can be build and used as a normal caliper, albeit cheaper at cost due to its plastic construction and not coming pre-assembled. It would come with 7 parts and basic instructions. Unbeknownst or perhaps not immediately obvious is that these kits are flawed. The inherent flaws to the kit are very deliberate, not only do they make the inherent problem of the tool visible, but also one that can be overcome ('fixed') by understanding the tool's mechanics (Which is understood by building it in the first place) and therefor being able to change the tool to the users desire (Appropriation).

For example here, the caliper comes without any scale. If the user would want to use it in the 'traditional' sense of the tool, it would have to re-write the (If desired) metric scale, but by doing so might question who decides that we do it this way, and gives the user the option to do it differently.

Some methods seem stronger than others (The current attempts are ordered in effectiveness from best to worst, the caliper being on the lower end, the platform on the high), and many different ways of doing this (And applying these methods to the camera) still need to be tried out and researched.

Eventually this will physically manifest itself in a single or a set of cameras (or/and possible workshops surrounding them), in a to be determined way of presentation, which will hopefully allow user interaction / participation within the exhibition presentation to experience / use the cameras (And thereby be influenced / made aware).

References

Neil Postman - Technopoly: The Surrender of Culture to Technology

Donald A. MacKenzie, Judy Wajcman - The Social Shaping of Technology

John Tagg - The Burden of Representation

Jonathan Crary - Techniques of the observer

Marshal McLuhan - Understanding Media

Langdon Winner - Readings in the Philosophy of Technology

Matthew Fuller, Andrew Goffey - Towards an Evil Media Studies

Aram Bartholl - Map

Matt Richardson - The Descriptive Camera