User:Mathijs van Oosterhoudt/chapter2

Chapter 2 (Draft)

Why is it important to subvert such choices?

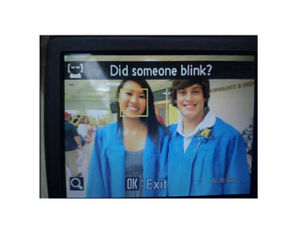

A logical consequence of how a tool influences us is that of its process or result. The way one uses a brush determines to a certain extend the size of the stroke and various other factors of the painting. This may seem like something that is easily taken for granted or insignificant, since one has the power to choose which brush one uses, but is not that straight forward. While one might choose which brush to use, it is still limited to the choice of brushes are available. Thus, this places part of that control over the stroke with the manufacturer of the brush. The same holds true for the camera, but with a higher significance due to the role photographs play in society and perceived authority. It has changed our perception of our surroundings and ourselves and continues to do so. The role of the photographer is dominant in choices regarding the photograph, but his or her decisions are, in turn, influenced or limited by that of the camera. What can be seen through the viewfinder or what fits the frame decides what we put in the frame or in older cameras with waist level finders, the height we have to hold the camera to even see the image deciding our viewpoint. In more modern cameras, the addition of digital operating systems allows for even more influence on us and our photographs, whether it is such methods of aiding the user as smile detection or that of facial recognition, often with a heavy social or racial bias, such as in the case of HP's facial detection algorithms not recognizing people with a dark skintone. In another case it was Nikon's smile detection, which would pop up the message "Did someone blink?" as it was trying to time the right photograph for the user.

Furthermore, photography as a technology is not only significant for cultural use, but the camera is and has been used as a scientific instrument since it's invention, early on often seen as a tool that exemplifies "how observation leads to truthful inferences about the world" (Crary, 1988, p.3). Where in a pre-photographic era scientists would illustrate what they saw through the microscope on paper via a camera obscura, leaving out "irrelevant details" (Daston and Galison, 2010, p.?) leading to biased registration, the camera could do this differently. It could capture that what was being witnessed through the microscope in such detail that no such thing had to be left out, setting in an era of mechanical objectivity: "The insistent drive to repress the willful intervention of the artist-author, and to put in its stead a set of procedures that would, as it were move nature to the page through a strict protocol, if not automatically." (Daston and Galison, 2010, p.121). They note that this strive for objectivity is in fact heavily influenced by how the scientist sets up the scene, chooses what to register and how said results are used (The human role in the protocol). They ignore, however, the human role of the creator of the machine; the camera.

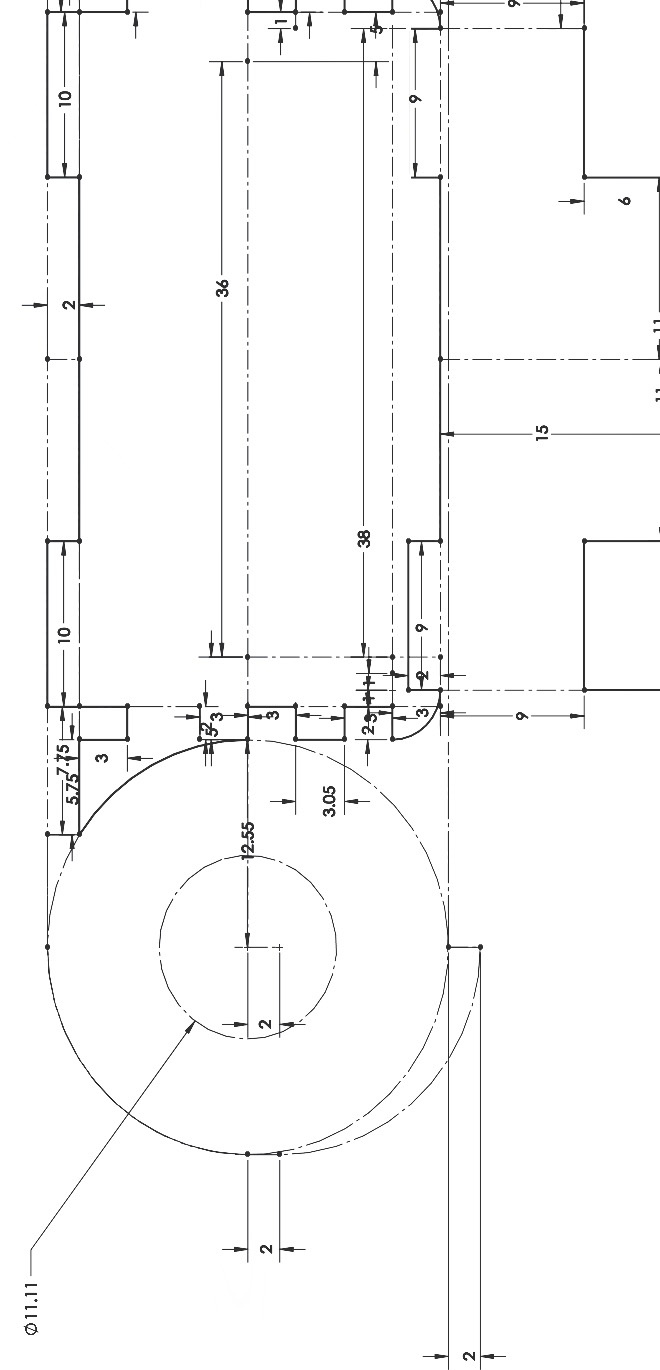

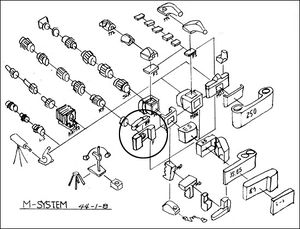

It is undoubtedly so that the camera changes our perception, so it follows from that changes within the camera in both significant cases in history as well as minor changes throughout variations of consumer products do lead to changes in how we both perceive and ultimately consume photographs. Since the user of the camera is not the creator or often even in the position of control to alter it, that power is taken out of our hands and held by the companies that produce cameras. Companies are quite logically pleased with this manner of control, although the influence of their choices are only guided by a singular goal: Financial gain. Being dependent on their company for the production of cameras is what keeps their business going, which is the deciding feature for many choices made within the company. Different companies design in different ways, whether its done by design teams or singular designers aided by engineers, but the market viability is of great concern, often leading to changes in the original design plans. In one such famous case, Maitani, one of Olympus' most famous designers in the past, was asked to design a new SLR system. This was 1970, and Olympus wanted to compete with the other big brands such as Canon and Nikon. Maitani, working on his own and free from the problem that haunts most team-based designs (That of creating the most agreed upon, thereby the most average), created a revolutionary system of blocks with each their own function. One could assemble their own camera exactly to one's need, whether you required an optical viewfinder, SLR viewing, waist level finder, 35mm film back, Polaroid back and so forth. The financial and marketing department of the company were less pleased, asking for "development of the same camera as the other maker's best seller." (Maitani & Akagi, 1999).

A similar issue could be noted in a recently developed camera by Ricoh, who proudly presented their prototypes of the new Ricoh GXR at the CP+ Camera and Imaging Show in 2010. The idea was simple, sensors continuously get better, but there's nothing wrong with the physical body, buttons and processor of the camera once already purchased. By allowing users to change the sensor, one could not only upgrade at a later stage to a newer and better sensor, but also to different lens mounts. Prototypes with a Leica mount and even one where the camera functions as a back for a Hasselblad were presented. Rumor has it that later in production, it was thought of as not commercially viable. Due to the camera relying on other brands' lenses and with no need to re-buy the body when it got better, the margins for profit were low. The camera did still reach the market, but instead of having interchangeable sensors, each sensor was paired with a different lens. Instead of having the option to upgrade your sensor, you now needed to have a different sensor for each lens: A camera planned to become the counter to planned obsolescence became one of the most prominent examples of it.

This is different from the first 30 to 40 years of the camera, where both its development and that of photography raised hand in hand. "In this early period subject and technique were as exactly congruent as they become incongruent in the period of decline that immediately followed" (Benjamin, 1931, p.517). Technology was often developed to the needs of the photographer, or by the photographer itself. The latter was possible due to the simplicity of the camera at this stage. It is not illogical that this first period of inventions were the most original; not only did these photographers and inventors have no preconceived notion of what a camera should look like, rather were driven by what it had to do, but they were also driven less by the need for sales. If round daguerreotypes needed to be made, a round camera was made. This changed with the onset of mass production of cameras and their commercialization. What is surprising, however, is that most cameras produced since that period are based on those first few ideas. Even the cameras we use today are very reminiscent of the first few inventions. The Kodak Brownie is almost identical to the first commercial camera ever made, simply smaller. The principle of the SLR system is even based on that of the mirror in the camera obscura. The major changes in camera history appear when the medium changes, the method to capture the photograph, rather than by actual change within the camera. This can be attributed to need for 'commercial viability': A camera made to serve a large market needs to appeal to as many people at the same time. That doesn't mean it serves the mass amount of people using cameras equally well, but a camera that serves a niche amount of users extremely well is less viable than that of serving the mass 'acceptably' well. Changes can be found when daguerreotypes went to printable glass plates (Gelatin), to flexible roll film (120), to smaller roll film (35mm) and the advent of the digital sensor.

Furthermore, whilst the influence on the user might be that of financial gain at the expense of the consumer, it also inherently possesses the ideologies present within these large scale companies. Winner describes how, while often overlooked or ignored, in the social shaping of technology, the ideologies of its creator do transfer to the 'thing' of creation, whether inherently visible in some cases or less so, in others. "first are instances in which the invention, design, or arrangement of a specific technical device or system becomes a way of settling an issue in a particular community. Seen in the proper light, examples of this kind are fairly straightforward and easily understood. Second are cases of what can be called inherently political technologies, man-made systems that appear to require, or to be strongly compatible with, particular kinds of political relationships." (Winner, 1980 p.123). The former instance applies to the use of camera in modern society and photojournalism, where there seems to be a commonly accepted thought that those privileged to own a camera or photograph as their living have the right to photograph those who cannot easily represent themselves in photographs. The latter instance however is of larger interest, as the way the camera is currently constructed and distributed fits within a neoliberalist view of the economy the market works in. However, the technology itself does not have to be, if applied differently.

This control is one that can be subverted in various ways. It's a market that has, through the years, build itself as an impenetrable fortress for most inventors after the advent of electronic and eventually digital cameras. That does not mean we should stop trying, but possibly take a step back and continue where the market has left the individual creator of the camera off. Continuing from where we still understand the camera, we can find ways of creating them, subverting the existing ones and open up the possibility of the self-made camera once more, thus giving the power of the camera's influence to that of its user.

Bibliography (To be formatted)

Walter Benjamin - Little History of Photography

Langdon Winner - Do Artifacts Have Politics?

Jonathan Crary - Techniques of the observer

Lorraine Daston and Peter Galison - Objectivity