The Cybernetic Jungle

The Cybernetic Jungle

Like many controversial conflicts during the Vietnam war, "Operation Igloo White" remains somewhat obscured to popular history. Considering its great potential as another bombastic propaganda film illustrating the ingenuity of the US military and its patriotic spirit, it is perhaps surprising that it hasn't yet been given the full Michael Bay treatment. Then again, one probable reason why Igloo White: The Movie hasn't had a cinematic couterpart is that it is considered to be a major military controversy, and another entry on the long list of induced Vietnam amnesia.

Despite its failure, Igloo White was an important precursor to the kind of remote-controlled warfare that forms a basis for the new vision of the US military. It set the precedent of ordinary soldiers fighting on the frontline from a computer terminal in a bunker, distant from the battlefield itself. While similar endeavors were explored during World War II and the MAD, early decades of the Cold War, Igloo White could be seen as the field test for contemporary drone warfare, and in this way only could it have been deemed a worthwhile campaign.

As with the majority of US military campaigns featuring experimental technologies, the raw materials for Igloo White were developed at MIT in the late 1960s with a R&D group known as JASON. The idea was to create a network of sensors along the Ho Chi Minh Trail, a transport route of strategic importance that ran through the jungles of North Vietnam into the South, through Laos and Cambodia. A variety of sensors were used in the operation: vibration sensors to detect movement of truck convoys, microphones to pick up the speech of the enemy soldiers, and even sensors that could detect the scent of urine. [1] The sensors were mostly dispersed by air - like seedlings, designed to embed themselves in the ground and appear like small plants, or get caught in the jungle canopy disguised amongst the trees, quietly emitting data streams via radiowaves. The result was a cybernetic jungle, a natural space invaded by micro-computers broadcasting a symbolic representation of their environment.

The network was controlled and observed from a US military command center (the Infiltration Surveillance Center - ISC) hundreds of kilometers to the North West in Nakhom Phanom, Thailand. Soldiers would turn up for work in a windowless bunker in full uniform, watching over the network for unusual patterns in the incoming data that might suggest suspicious activity. By analysing the data collected from a number of sensors proximate to one another, the size of a convoy could be ascertained, and perhaps what type of vehicles are being used. The soldier could then order an air strike of the area:

- "The planes' navigation systems and computers automatically guided them to the "box", or map grid square, to be attacked. The ISC central computers were also able to control the release of bombs: the pilot might do no more than sit and watch as the invisible jungle below suddenly exploded into flames. In most cases, no American ever actually saw the target at all."[1]

Through this remote system, the enemy is replaced by symbols that represent the enemy: flows of numbers, or a glowing white light on a computer monitor. The only sensor that apparently managed a direct representation of the enemy was the microphone, relaying the voices and sounds back to the ISC where it could be recorded to tape for later analysis. But indeed, by abstracting the human-enemy into a continual data stream, a paranoid curiosity can begin to take over: how do I know this symbol signifies the actual presence of the enemy? Is it a glitch? Is the enemy playing tricks on me?

At a cost of about one billion US dollars per year to operate, Operation Igloo White was hardly an incidental military investment. The expected return was control over the regional logistics, and to further the policy of containment. Operation Igloo White was declared a great success by the US, but in truth the figures detailing the cost of destruction to the Vietcong were greatly inflated. The amount of airstrikes triggered and delivered by the network may have indicated a victory of vast destruction, but after further analysis, the statistics did not make sense. The Americans had claimed the destruction of a number of trucks along the trail that exceeded some estimates of the number of trucks in the entire country at the time.

- "The guerillas had simply learned to confuse the American sensors with tape-recorded truck noises, bags of urine, and other decoys, provoking the release of countless tons of bombs onto empty jungle corrdoes, which they then traversed at their leisure." [1]

The curious paranoiac would have been right to become anxious: the Vietnamese soldiers began to learn and adapt to the cybernetic jungle, using the assumption that the sensors broadcast an objective truth to their advantage.

Horses and Bayonets and Unmanned Aerial Vehicles, Oh My!

On the 22nd October, the third and final 2012 US presidential debate between Barack Obama and Mitt Romney was viewed on television by almost 60 million Americans, with many more all over the world following online and offering their commentary on social media sites.[2] The two previous debates had offered moments of political surrealism, with Romney declaring his love for Sesame Street's Big Bird followed by the bizarre turn of phrase "binders full of women" in the second debate. Both moments were immortalised in the short-term memory of internet culture through a viral flurry of hashtags, blog posts, and tumblrs full of gifs. So a captivated audience of digital natives gathered to watch the final debate, networked devices in hand, waiting for the next "moment" - if they were quick enough, they might get the tumblr url first.

The supposed subject of the debate was foreign policy, although Obama's US military policies were drawn into the spotlight on numerous occasions, eventually giving rise to a minor highlight of what was generally deemed a dull debate. Romney pressed Obama on planned cuts to the US military budget:

- "You mention the Navy, for example, and the fact that we have fewer ships than we did in 1916. Well Governor, we also have fewer horses and bayonets."[3]

Cue a barrage of collage: Obama's face photoshopped onto scenes from the American Civil War; mash-ups with binders full of women, horses, and bayonets; and numerous gifs featuring Mitt Romney and unicorns.

The noise that followed Obama's wry comment drowned out his intended point that tells us a lot about the future of warfare. In January 2012, Obama announced a defence review, stating that he planned to cut $500bn from the Pentagon's budget over the next ten years. [4] The Pentagon's "leaner" armed forces will rely on far fewer ground troops, but will use technologies such as drones to make up the shortfall.[5]

The rationalisation of the US military structure into a bodiless entity is the logical conclusion of a process that had begun toward the end of World War II. The development of the missile removed the need for the horse - the "horse" being the vessel that carries the corporeal solder into battle. An army did no longer had to set foot on the battlefield to win a war: soldiers could attack from computer terminals, distant from their targets. During the extended period of unprecedented military investment that followed the end of the second world war, the US military explored more radical systems for remote warfare, leading to strategic and ambitious experiments such as Operation Igloo White.

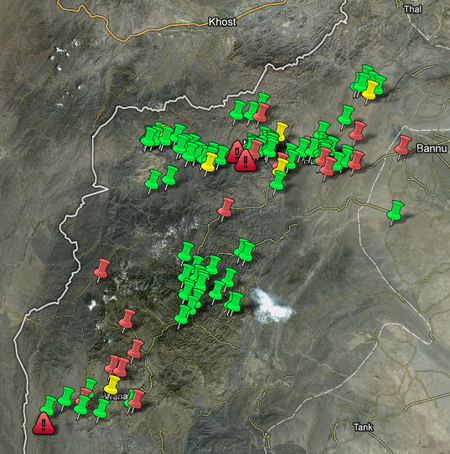

The logical extension of the Igloo White experiment is the development of the highly sophisticated UAVs that are being used in raids on suspected Al Quaeda and Taliban strongholds in northern Pakistan as part of the War on Terror. [6] Drone attacks peaked during the Obama administration: according to the New America foundation, there was almost 50% more deaths attributed to drone attacks in 2010 than the second highest year recorded. Civilian casualties account for a slim portion of the annual total of recorded deaths, dropping significantly from the Bush administration years to 0% in 2012. Contrarily, the Bureau of Investigative Journalism reports the possibilities of civilian deaths on numerous occasions this year.[7] To take the New America Foundation data at face value, drones offer a previously unheard of level of accuracy when targeting militants. Yet, questions over their legality persist - the technology is perhaps being implemented faster than legislation can keep up. The Guardian quote a note issued by the UK Ministry of Defence: "In particular, if we wish to allow systems to make independent decisions without human intervention, some considerable work will be required to show how such systems will operate legally."[8]

What happens to the mind of the drone operator, being displaced from the conflict region and experiencing war as information transmitted through a computer interface? It is perhaps natural to assume that the process of launching a missile is somehow made easier through the medium of the computer, as it presents information of combat via an interface more commonly associated with simulation. The New York Times presents two articles that present different views of the effects of drone warfare on the mental health of the operators. Quoting a survey published by the US Air Force, the New York Times states that the biggest source of stress for operators is not the problematic ethics of drone combat, but the "long hours and frequent shift changes because of staff shortages."[9] A second article present a more empathetic picture of the operators, describing how a militant target can become "humanised" in the mind of the operator as a result of the close proximity allowed for by drone surveillance. One operator is quoted as saying: "There was good reason for killing the people that I did, and I go through it in my head over and over and over[...] But you never forget about it. It never just fades away, I don’t think — not for me."[10]

The process of the dematerialisation of the US army could be said to have begun during the Cold War during experiments such as Igloo White. In the drone campaigns on northern Pakistan, the battlefield has lost its physical form and become information, mediated by networks and computer interdaces. The trend of the automatisation of combat results in the further removal of the human guilt-reflex that acts as a mechanism to protect the safety of civilians. The responsibility of error becomes a legal and ethical grey area - to outsource the process of due consideration to an automated system would appear to be a dangerous development. In the event of a grave error, there is no obvious figure who could be held accountable. While the technology of Igloo White was much less sophisticated than what is available to the contemporary US military, it's spectacular failure does not inspire great confidence in the increasing trust placed in automated military systems. Igloo White was initially reported to be a great success, efficiently disrupting the flows of munitions from the North to the South of Vietnam, but in reality the cybernetic jungle created by the US military was unreliable at best. While the internet has allowed for investigative journalists to pool their information and create a platform to monitor and criticise the ongoing drone campaigns, the full extent of its mistakes and catastrophes may not be public knowledge for some years to come.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Edwards, Paul N. Closed World: Computers and the Politics of Discourse in Cold War America (1996) p3-8

- ↑ Nielsen Wire: Final Presidential Debate Viewing Figures

- ↑ The Atlantic: 'Horses and Bayonets' Goes from Obama's Mouth to Parody Tumblr in 9 Minutes:

- ↑ BBC: Obama unveils new strategy for 'leaner' US military

- ↑ Huffington Post: Military Budget Cuts: Pentagon Unveils 2013 Plan

- ↑ New American Foundation: The Year of the Drone

- ↑ Bureau of Investigative Journalism: Obama 2012 Pakistan strikes

- ↑ The Guardian: The legal dilemma over drone strikes: justified killings or war crimes?

- ↑ NYT: Air Force Drone Operators Report High Levels of Stress

- ↑ NYT: A Day Job Waiting for a Kill Shot a World Away