Some notes on A New Economics of Community and The Land (The Nation)

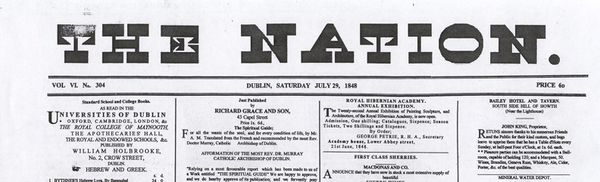

In 1856, some years after the Great Famine in Ireland, an article appeared in the Irish nationalist newspaper The Nation titled A New Economics of Community and The Land. While the true author of the article is not known, it was credited under the pseudonym Thomas Brennan, coincidentally a namesake of the eventual founder and secretary of the Irish Land League in the late 1870s. The Nation had already become well known as the platform for radical nationalist discourse by the time the article was published, with its founders involved in various anti-union political and social organisations, such as Young Ireland. One of The Nation's recurrent themes was the issues surrounding tenant's rights: centuries before, the Penal Laws had removed the rights to land away from Irish natives and subsequently awarded them to a new class of wealthy Protestant settlers from England. The Irish farmers then had to rent their land from their new landlords - a system which continued throughout the 19th century during the Great Famine. The result was further hardship on the farmers, who were faced with the choice of selling their agricultural produce to pay rent on their land, or feed their families. The protests surrounding tenant's rights during the Great Famine inevitably lead to numerous impassioned and poetic articles in the Irish nationalist press, but Thomas Brennan's text stands out for its radical views on community and its focus on pragmatic economics. At the time of its publication, the article had little political influence, and is still largely forgotten to contemporary readings of Irish history.

Brennan's article reads like a proposal for the practical realisation of a new socioeconomic system, supported by a number of illustrations elaborating on specific details. His introduction is a brief overview of the change in labour practices since the start of the 19th century. Brennan describes how, as a result of the industrial revolution, labour was being deliberately centralised by the ruling classes in cities through a variety of gradual processes. Between the introduction of agricultural machinery, the resulting redundancy of many farm labourers, mass emigration, and the availability of unskilled work in the industrialised urban centers, the population was greatly redistributed and becoming increasingly concentrated around the cities and large towns. Brennan described this as "the great tragedy of modern Ireland", arguing that it was triggering a "collapse of community" and the beginning of the end of traditional Irish culture.

Brennan's answer to this "great tragedy" was the formation of a new socioeconomic system based around a trading-network of rural communities, with the population of each community controlled with respect to the sustainability of its local resources. A few years previously, Young Ireland had already commissioned a survey detailing an estimation of yearly consumption of various necessities in rural areas. From this information, Brennan could calculate the levels of production required to sustain a community of a given population, and also the amount of land required to reach these levels of production on a sustainable basis. Per hundred of population, Brennan specified the required acreage of arable land, number of animal stock (cows, pigs, sheep), barrels of water, tons of fuel (wood or turf) would have to be available to sustain them. Communities would be built on the following laws:

- The community's population must be maintained at a sustainable level with respect to the availability of natural resources.

- The labour, arable land, animal stock and environmental resources (wells, woodland etc) would be shared in ownership and responsibility by the people of the community.

- Each "family" within the community is provided with one house by the community, which is considered private property owned by the family.

- A family is defined as a married couple with or without children, or an independent male over the age of 28.

- Upon the death of a "family", and with no children to take the land, the property is returned to the community for re-allocation.

- Each community would have land specifically allocated for staples that must be grown on an annual basis (potato, oats, for example).

- Each community would also have land designated for supplementary produce.

- The types of supplementary produce would be decided three years in advance at the annual inter-community meetings. Each community would then produce different goods, which could then be traded between them.

- Inter-community trade would be performed according to a natural economy - i.e. barter exchange.

Brennan's proposal is likely to be at least partially inspired by The Communist Manifesto, which had its first English translation about 5 years previously. Marx's descriptions of the centralisation of population and the exploitation of the proletariat through the mechanisms of industrial production must have resonated with Brennan's own experiences in Ireland during the famine years. Despite calling out for a practical experiment of his vision of utopia, the article failed to trigger any response for at least a decade after its initial publication.