Scaling + Platform: A Computational History

<slidy />

Introduction

While computational media (the so-called multimedia) are consistently packaged in "seamless" and immersive experiences, the particularities of different materials and methods persist in both making and preservation and are despite the illusion, vitally important, to those who aim to work with them. The actual (digital) hand work of producing the seamless experience is itself highly heterogeneous, mixing different techniques, animation and photographic, analog and digital, to concoct a careful coctail of pre-rendered elements bound by clever algorithms that hold the pieces together and give the illusion of continuity. The most sucessfull of the experiences are often the ones that push the limits of their framing platforms, be it the spatial or temporal limitations of a recording medium such as the CD-ROM or flash memory, or the computational speed or energy limits of a particular plafform's CPU. ( Tensions between the limitations of platform and the suggestion of seamlessness. )

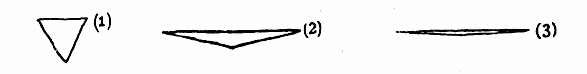

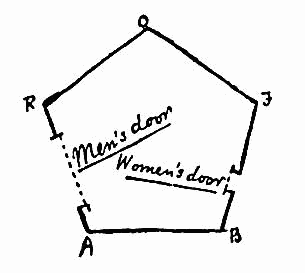

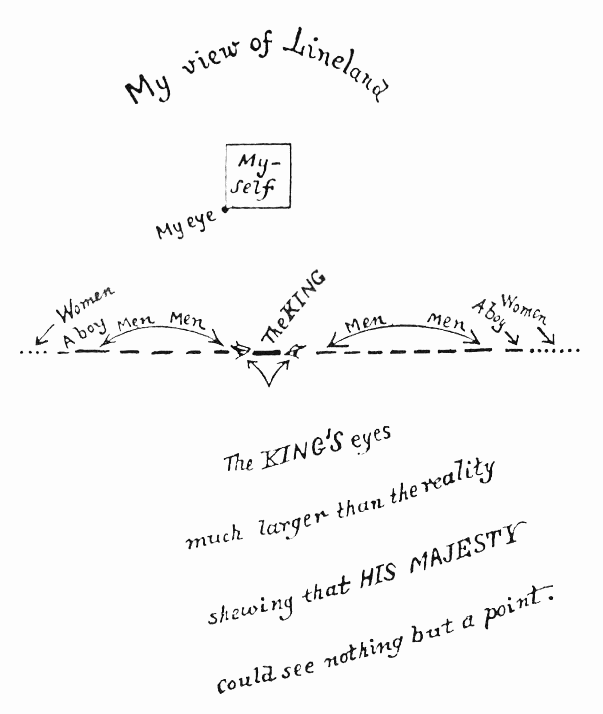

In Abbott's Flatland, the reductive logic of viewing the world with geometric constraints helps to bring other social dimensions (gender, class relations) come to the foreground. ( In Media Ecologies, Fuller describes art as exploring all possible scales and relationships of a system. )

What implications does the inevitable decay of platforms make to a work as other seams emerge through bit rot or later translation to a newer platform. (Migration to a new platform: think VHS on YouTube, video game emulation, net art through wayback)

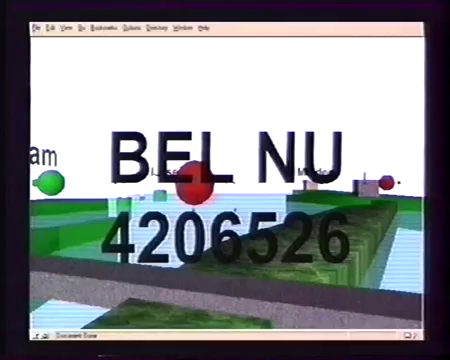

The work of JODI highlights this fragility by simply playing these systems to their full potential, rather than carefully staying within the polite limits of expected use and instead programmatically driving their inputs through the full cycles of poteniality, the conceptual cracks begin to show, as the seamlessness of the illusion in fact starts to reveal the conceptual gaps that were present but in normal use are kept just out of sight.

Can a seamless navigational space be used strategically to in face highlight the incongruities of its assembled elements? (Thinking Nikos's sketches here). What do the lessons of collage bring to the cut and paste world of web pages where typography, bitmap, vector graphics, audio/video, and texture-mapped 3d graphics coexist in a single "document" and are composited by one's browser.

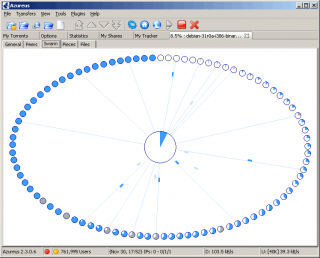

Scaling distribution

BitTorrent is a key example of where technical protocol intersects the social. When downloader becomes also uploader, legal implications engage that expose users of the protocol to prosecution for "distributing" works. The protocols amplification of the facility of distributed copying and distribution capabilities of the Internet.

Recursion

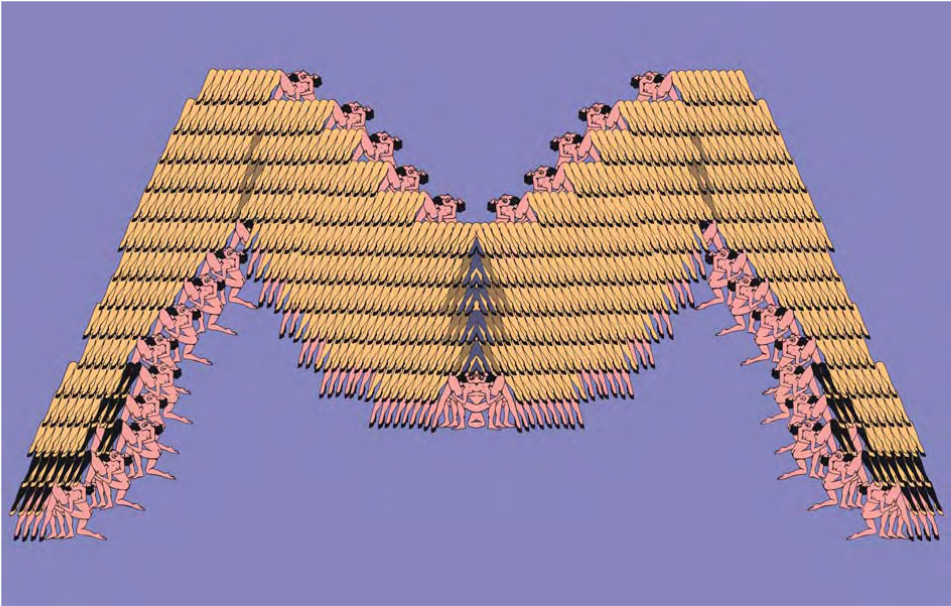

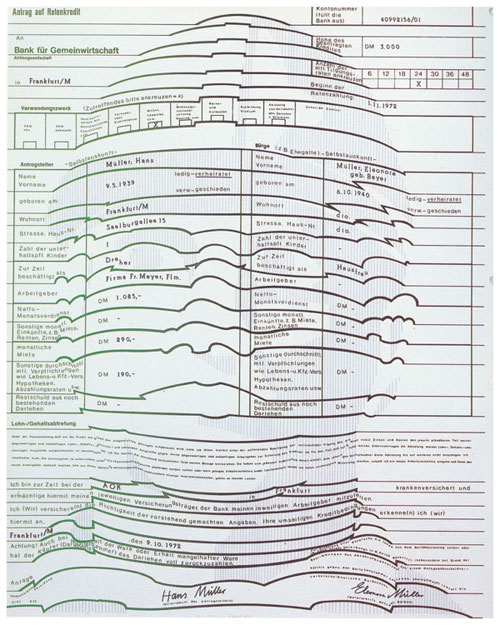

Thomas Bayrle's work as a modern retake on Escher recursive hands as his "superimages" reflect a larger media ecology and industrial scale of image manufacture through recursive construction of constituent image.

Scrolling (600 BC)

A Torah scroll

Written entirely in Hebrew, a sefer Torah contains 304,805 letters, all of which must be duplicated precisely by a trained sofer (“scribe”), an effort which may take as long as approximately one and a half years. An error during transcription may render the sefer Torah pasul (“invalid”). According to the Talmud (the oral law of the Jewish People), all scrolls must also be written on gevil parchment that is treated with salt, flour and m'afatsim (a residual of wasp enzyme and tree bark)[clarification needed] in order to be valid. Scrolls not processed in this way are considered invalid (Hilkoth Tefillin 1:8 & 1:14, Maimonides). In addition, the Talmud (in tractate Bava Batra 14b & Gitten 54b) states that Moses used gevil for the Torah scroll he placed into the Holy Ark.

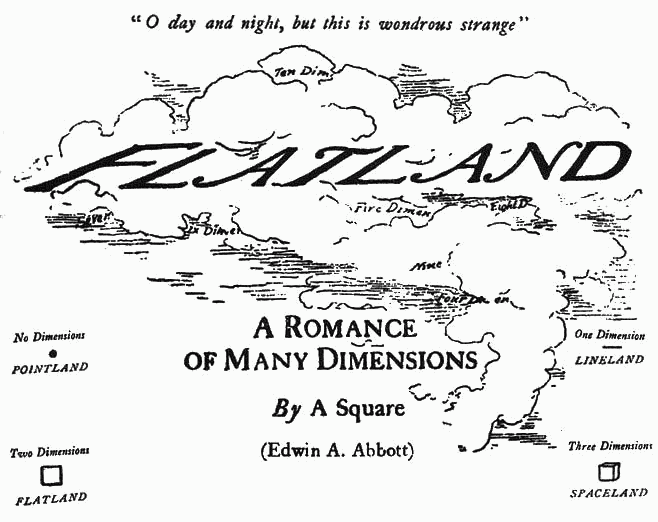

Flatland (1884)

Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions

By A Square (Edwin A. Abbott)

Dedication:

To The Inhabitants of SPACE IN GENERAL And H. C. IN PARTICULAR This Work is Dedicated By a Humble Native of Flatland In the Hope that Even as he was Initiated into the Mysteries Of THREE Dimensions Having been previously conversant With ONLY TWO So the Citizens of that Celestial Region May aspire yet higher and higher To the Secrets of FOUR FIVE OR EVEN SIX Dimensions Thereby contributing To the Enlargement of THE IMAGINATION And the possible Development Of that most rare and excellent Gift of MODESTY Among the Superior Races Of SOLID HUMANITY

Escher (1948)

- The Mathematical Structure of Escher’s Print Gallery

- Using Maths to fill the gap

- Image source: Escher and the Droste effect

Sketchpad, Ivan Sutherland (1963)

- Vector graphics

- Language of constraints

Paul Sharits, Sears Catalogue, Word Movie (1965-1966)

Sears Catalogue, 1965

Word Movie, 1966

The Flicker Film as an example of a counter-engagement with the cinematic illusion of apparent motion through continuity.

The "flicker effect" for which these films are named is an intrinsic but ordinarily unnoticed feature of the phenomenology of film viewing. Films create the illusion of objects moving on screen by projecting a rapidly pulsing (flickering) beam of light through a series of still frames that are transported intermittently past the light source." Each frame contains a phase of an action (either photographed or animated) and these phases must be coordinated (for example, they must be consecutively ordered) so that, when projected, they fuse into the percieved image of an object moving continuously through a stable setting

In his flicker films, Sharits disrupts this process. He replaces the consecutive phases of action with solidly colored or black or white frames. The effect is literally dazzling. The viewer sees often violent bursts of light whose color and intensity are functions of the speed at which the colored frames and the complementary colors of spontaneously induced afterimages change. The oscillating colors not only foreground the pulsing light beam, they also reflexively remind the viewer of the physical limits of the frame and of the surface on which films are projected. When colors change slowly, a flat, undifferentiated field fills the entire image.

As the speed increases, however, random shapes appear that seem either to sink into an illusory depth or to project into the auditorium space . A dynamic, purely opti- cal space, shifting between two and three dimensions, which is characteristic of our perception of the space in all films, is created.

Source: Paul Sharits in Film In The Cities, Walker Art Center 1981

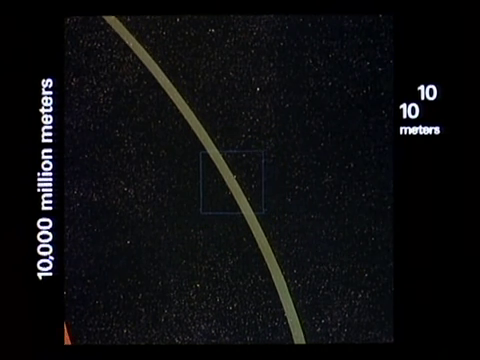

Powers of Ten (1968, 1977)

Charles and Ray Eames, 1968 (sketch), 1977 (final version)

Thomas Bayrle, "Superimage" prints ( 1970s )

Erkki Kurenniemi, DIMO-O (1971)

Aspen Movie Map (1978)

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aspen_Movie_Map

- http://www.inventinginteractive.com/2010/03/18/aspen-movie-map/

Myron Krueger, Videoplace (1985)

Myron Krueger at the University of Connecticut's Artificial Reality Lab

Jeffrey Shaw: Legible City (1989)

MediaArtTube Category: Pioneers of MediaArt In The Legible City the visitor is able to ride a stationary bicycle through a simulated representation of a city that is constituted by computer-generated three-dimensional letters that form words and sentences along the sides of the streets. Using the ground plans of actual cities - Manhattan, Amsterdam and Karlsruhe - the existing architecture of these cities is completely replaced by textual formations written and compiled by Dirk Groeneveld. Travelling through these cities of words is consequently a journey of reading; choosing the path one takes is a choice of texts as well as their spontaneous juxtapositions and conjunctions of meaning. Source

Myst (1993)

- "Killer" CD-ROM (along with The 7th Guest)

- Rand & Robyn Miller

- Personless space

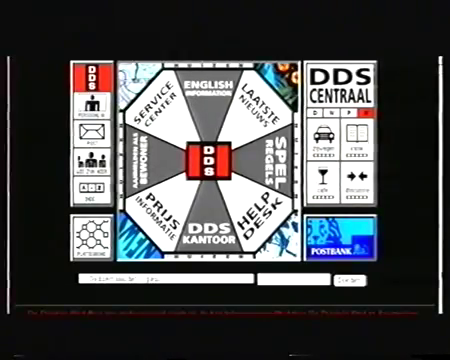

De Digitale Stad (1994)

The nucleus of the digital art community is the Temporary Museum. Like a real museum, you can browse through collections of art and objects, arranged and selected by the museum's curator (or beheerder as the anonymous curator prefers to call himself). Ironically, the Temporary Museum is less temporary than its real-world counterparts. When an exhibit is over, it is simply moved into a warehouse area, where it remains less prominently on display. And as art provides an identity to the virtual Amsterdammers, so civic pride is a prominent feature of the gallery. One section of the museum displays an ever-growing collection of ever-more-futuristic versions of Amsterdam's twin-lions coat of arms, all contributed by local artists and would-be artists.

In the beginning, everything was available and everything was free. The City of Amsterdam financed the construction of the digital city. For six weeks, everyone could get online for free, thanks to a deal with the local telephone company, and enjoy full Internet access. After the trial period, citizens could still get into the Digital City for only the price of a local phone call, but ventures into the cosmos of the Internet were severely restricted. At the same time, the Ministries of the Interior and Economic Affairs stepped in to help Amsterdam with the project's finances.

A consequence of the restrictions on Internet access was that many of those lured into the city signed up with commercial Internet service providers to maintain full net-roaming privileges. And the Inter-net service provider most chose was a new venture set up by veterans of Hacktic, catchily called xs4all. Some in the Digital City grumble that the ex-hackers have made the switch from publicly financed idealism to privately profitable entrepreneurialism with worrying speed. But the more heated arguments concern that inevitable bogey-man of online worlds: electronic commerce.

VRML (1994)

Virtual Reality Markup Language -- proposed by Dave Raggett, in a document called Extending WWW to support Platform Independent Virtual Reality

De digitale stad + VRML + Phone ins = Democratic Urban Planning ?!

De digitale stad + VRML + Phone ins = Democratic Urban Planning ?!

Information Landscapes (1994)

- Muriel Cooper (http://messagesandmeans.com/, http://www.inventinginteractive.com/2014/03/27/messages-and-means-muriel-cooper-at-mit/)

- Visible Language Workshop

- Infinite zoom, Transparency, Focus, Layering

- Muriel Cooper's VLW / Information Landscapes

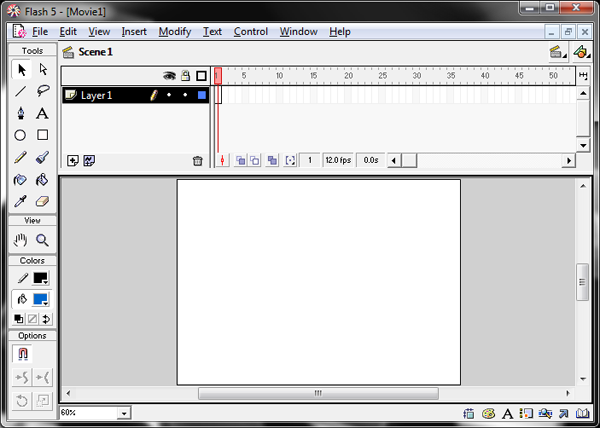

Future Splash (1996)

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/FutureSplash_Animator

- http://www.pxleyes.com/blog/2010/07/evolution-of-flash-from-1996-to-2010/

John Maeda's Shisedo Calendar (1997)

Apartment (2000)

Marek Walczak and Martin Wattenberg, mw2mw

Rose Lowder, Voiliers et Coquelicots (2001)

SVG (2001)

BitTorrent (2001)

BitTorrent is a network protocol designed to scale with use; it does so by distributing the work to it's users and operating in a radically decentralized fashion. As new downloaders (peers) join, the protocol adapts such that the efficiency of distribution increases. This in contrast to the traditional web protocol HTTP that degrades in performance as usage grows.

Second Life (2003)

JODI, Max Payne (2005)

Flash (2005)

http://www.pxleyes.com/blog/2010/07/evolution-of-flash-from-1996-to-2010/

YouTube (2005)

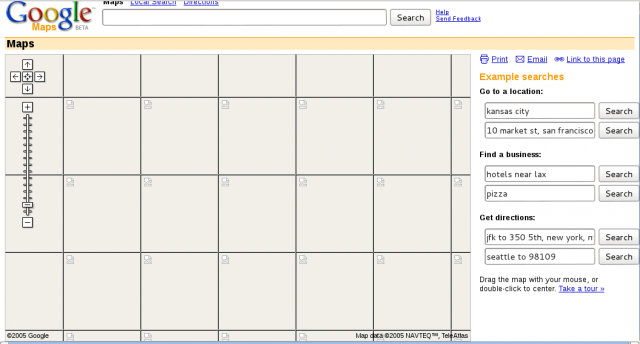

Google Maps (2005)

Alexei Shulgin, Aristarkh Chebyshev, Super-i Real Virtuality System (2005)

Google Street View (2007)

iPhone / Pinch to Zoom / Swipe (2007)

JODI, Geo Goo (2008)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7GB9Txb5_0E

Prezi (2009)

Prezi, according to its promotional videos, uses "zooming" and graphical overview of its seamless power point style presentations to provide:

- easier to understand,

- more memorable presentations that lead to

- rampant consumerist behaviours

- http://prezi.com/create-better-presentations-5/?gclid=CN7-9euz4L0CFWoCwwodB34A5w

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prezi

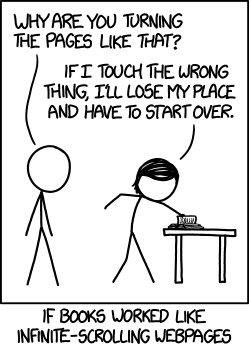

Infinite Scroll

- aka Bottomless pages

- https://xkcd.com/1309/

- Reasons not to use Infinite Scroll

Additional Resources

- No to NoUI, Timo Arnall

- Relearn 2013 Publication in particular the topic "Can it scale to the universe"