Rossella: Foucault, Campanella and Madness in the 16th Century

“I have nothing left but words and reason.” — Tommaso Campanella in a letter to Philip III, late august 1606.

The article by Joseph Scalzo explores the connection between Foucault’s definition of madness at the beginning of the modern era (16th century) in relation to the trial of Dominican philosopher Tommaso Campanella. Campanella is chosen as the exemplary case illustrating late Renaissance notion of madness also for the way the Dominican friar exploited the system to his own advantage. His trial against the inquisition is exemplary in that its outcome was starkly different from other similar legal proceedings, as the one which involved another Dominican philosopher, Giordano Bruno, who was eventually burned at the stake.

Campanella was seen for a long time as a dissimulator, as someone who feigned madness only as an extreme measure to have his life spared. This approach has been the most popular one since Luigi Amabile, one of the foremost researchers on Campanella, proposed it in his studies published at the end of the 19th century. Amabile’s thesis was particularly successful because it explained in very practical terms the issues involved in Campanella’s sentencing and offered a clear-cut interpretation of the events as they were recorded at the time of the trial. However, opening up to Michel Foucault’s own definition of the idea of madness in the Renaissance (in special way, his “animal solidity of madness”), Campanella can be seen rather than as a dissimulator as a “great survivor who had been taught the skills and strategies of survival in a harsh social and political world.”

This theory introduces a different take on Campanella’s feigned madness, one that is more complex than the simplistic, although admittedly effective, view proposed by amabile. the “survivor” interpretation emphasizes campanella’s own sense of gamesmanship, and considers him as somebody who played a very dangerous game against authority, and did it fully consciously, knowing his odds all along. the veglia torture that the friar went through before he was handed his sentence of life imprisonment is therefore an integral element in explaining and putting into perspective both the inquisition’s final ruling (that is, Campanella is mad and therefore cannot be sentenced to death) and Campanella’s own exploitation of the system.

In his Madness and Civilization (quoted in Scalzo, 1990), Foucault argues that in late Renaissance madness was seen as a disease with very specific and recognizable features. The madman was diseased in that he displayed characters that were not anymore proper of the human, of a sentient being, but were rather proper of the beast. Like the animal, the madman could endure pain and misery endlessly because the very nature of madness would render him numb to sufferings of any kind. The bestiality of madness would therefore be a sufficient and reliable parameter on which to base a diagnosis to determine whether a subject was or wasn’t mad. Generally speaking, this view was maintained well into the late 19th century.

Foucault’s description of madness in the late renaissance matches what the inquisition based its rulings on in cases like Campanella’s. To streamline the trials, certain tortures were devised especially to grant the judging panel the means to determine with certainty whether an insanity ruling was or wasn’t in order. If for instance certain tortures were endured by the prisoner, with the prisoner showing erratic behavior with no visible signs of suffering, he was ruled as insane, even in the presence of other clues indicating he was, in fact, sane. The veglia torture, which was particularly hard to endure both for its cruelty and for its extreme duration, was generally successfully employed as an indicator of the prisoner's soundness of mind. Its duration made it especially effective for the purpose and put in the hands of the Holy Office a legally secure instrument on which to form a verdict.

The singularity of Campanella’s case—as opposed to others from the same historical period, like the infamous trial against Bruno—resides in that the friar was well acquainted with the Inquisition and with its judicial system, as he had already been condemned for heresy in multiple previous instances—although the other times he had been eventually acquitted. moreover, as somebody with a strong interest in magic and science, he was also familiar with contemporary studies of magical medicine, which included diagnosis and treatment of mental insanity. He therefore knew what constituted insanity in accordance with the descriptions that were commonly accepted at the time. This explains how, compared to others, the friar had the advantage of sharing a degree of knowledge with his persecutors. Campanella, the author argues, could enjoy the luxury of turning this knowledge, acquired through personal interest and experiences, in his favor. His course of action shows that his was not only an act of self-preservation, but a strategy to undermine and mock the very system he was up against, to demonstrate the fallacies that constituted the very core of the inquisition’s ability to judge.

Campanella’s stratagem went through different stages. He devised an elaborate although rather risky plan to prove his madness. it’s important to remember that at the time he had two different trials pending, one against the roman catholic church for heresy and the other against the Spanish crown for treason. Campanella only had first-hand knowledge of the workings of the inquisition, as he had never been arrested and detained before by the Spanish. In addition to this, rumors circulating at the time surely known to Campanella implied that there was for him a slight of chance of papal intercession. Even in the case the rumors proved to be unfounded, it only makes sense then that he would take the risk and prefer to confront the roman church rather than the Spanish crown.

While in prison in Naples, awaiting an almost certain damning sentence in both trials, on the Easter Sunday of 1600 Campanella set the bedding of his cell on fire under the watch of his jailer. He accompanied the act with other broken and incoherent actions and speech. Given these new developments, the civil trial against the Spanish crown was temporarily postponed; instead the Holy Office was granted permission to proceed with the heresy trial first. In the month of may, 1600 Campanella, whose madness at this point was deemed feigned, was tortured and interrogated. Behaving in uncooperative and bizarre manner, in this occasion he left his persecutors frustrated. Interrogated other times after this episode, he always showed a highly eccentric behavior, comprising strange disposition and nonsensical talk, all of which didn’t provide inquisitors with solid material for a ruling. Repeated evaluations in the course of the months had managed by November of the year 1600 to convince the Inquisition that the prisoner may be in fact totally deprived of a sound intellect. Several eyewitnesses, including the jailer, were heard in relation to Campanella's madness, and the general consensus was that the prisoner had behaved erratically also in front of them. Still, a final proof was needed before a verdict could be reached. This is when the veglia torture, to be administered under surveillance of two doctors, was ordered. On June 4, 1601 the torture session was started; it would last about forty hours altogether.

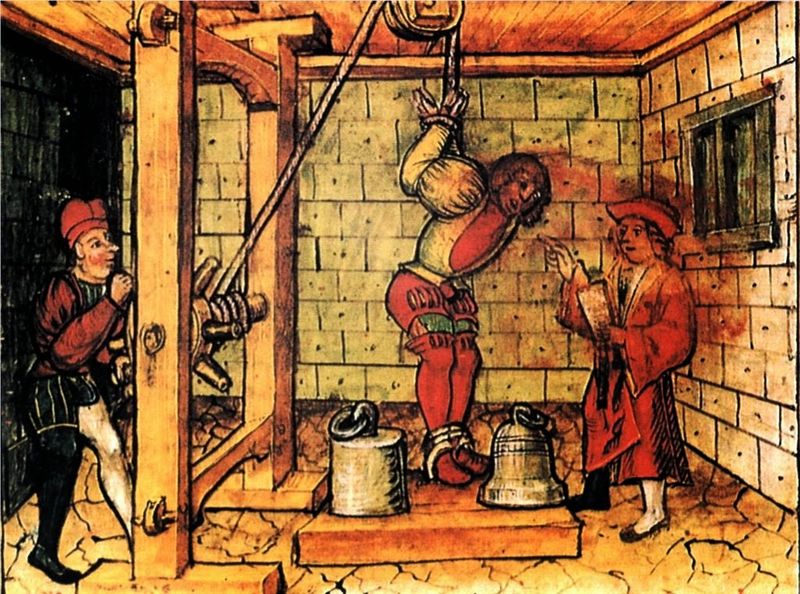

The veglia (Eng. wake) was a torture devised in early 16th century by jurist Ippolito de Marsilius that consisted, as the name suggests, in sleep deprivation. The original form was however modified and complicated by the Inquisition. In its upgraded form, the prisoner was hung over his toes by means of a rope tied firmly around his arms, putting him in an unnatural position which caused great strain on shoulder blades. A seat studded with sharp nails was then placed behind him, as to prevent the prisoner from relaxing his muscles at any time. While under torture the prisoner underwent interrogation; his manner of answering and his general demeanor were considered enough to judge his soundness of mind.

During almost forty hours of torture, Campanella, who was helped in this by his strong constitution, never betrayed himself and showed again the stubborn uncooperativeness and erratic behavior expected of a madman. This was seen by the holy office as a sufficient proof of his insanity. At that point, that the appointed doctors still doubted actual insanity didn’t matter any longer. Also, any evidence collected after the torture was irrelevant, including Campanella's own disdainful admission to his jailer right after the ordeal was over, "what did they think, that i was a prick who intended to talk?" (in Amabile, 1882, p.503)

Therefore, through his playing by the book as per the inquisition’s own internal rules, the friar had won his bid against the system and as a result he had fully earned his sentence. the actual ruling that sentenced him to life imprisonment was promulgated on January 8, 1603. At the time, this was considered a highly unusual verdict, especially considering the fact that Campanella was a recidive heretic. The friar would spend the next twenty-seven years in jail, writing on various subjects, especially politics, science and philosophy, and composing many letters appealing for his release.

Sources

Amabile, L. (1882). Congiura, vol. 3. Cav. Antonio Morano Editore, 1882.

Campanella, T. (2010). Lettere [1591-1639]. Ed. G. Ernst, 2010.

Scalzo, J. (1990). Campanella, Foucault, and Madness in Late-Sixteenth Century Italy. The Sixteenth Century Journal, vol. 21, no.3, pp. 359–372.