User:Silviolorusso/research-method/outline1

A non-digital journey into cybernetics

Since the '50s, the cybernetic metaphor extended way beyond the borders of technology. It radically affected and reshaped the common interpretation of society, environment and mind. Putting computers aside, there are several artifacts that keep trace of this transformation. Through a close observation of these, it is possible to identity the values that the cybernetic metaphor had taken from time to time: propeller for collaborative practices, symbol of alienation and dehumanization, model for an extended community spirit and instrument of revolt against the dominant hierarchies. In particular, four different artifacts over twenty years (60's-70's) will be explored:

- punch cards

- the Whole Earth Catalog

- Radical Software magazine

- and the DIY manifesto “Computer Lib/Dream Machines”

The exploration will be conducted in the light of our contemporary networked environment, trying to gather informed interpretations of it.

The punch card and the human being

The history of punch cards by far precedes the advent of cybernetics and computers: the oldest ones date back to the first half of the eighteenth century. However it's only in 1890 that Herman Hollerith began to employ punch cards as devices to store data that are meant to be read by a machine. Punch cards brought large advantage to the American federal government by making the 1890 census' process faster and easier.

Over the following decades their use became widespread also among private companies: thus they started to send punch cards themselves as bills. At the same time, computer and cybernetics were affecting the imagination of the population, causing a mix of fascination and anxiety. Consequently punched cards took on a negative symbolic value: they suggested hyper-rationality, dehumanization and conformity. Mirrored in the punch cards, people saw themselves as mere numbers.

This vision became explicit at Berkeley -where punch cards were used to keep track of students' registrations and marks- through the protests of the “Free Speech Movement”. The target of the critics was in first place university itself, seen as a “knowledge factory”, where “deviations from the norms are not allowed”. “Do Not Fold, Spindle of Mutilate” -the warning printed on the cards- became both a slogan in defense of the students and the inspiration to subvert these symbols of bureaucratization. Some students began to wear the cards as a sort of technical equivalent for soldier tags of prisoners' codes. Others went further, burning their own cards in order to express their freedom.

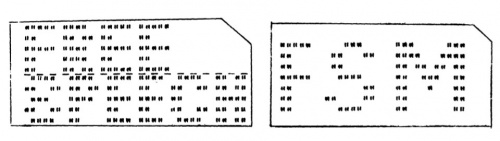

But the most interesting subversions of the punch cards regarded the technical appropriation or conversion. The students showed their technical control over the machine punching textual obscenities into some of the cards and then mixing them up with the official ones. Technical conversion was carried out punching holes in the shape of letters on cards. Composing such words as “strike” or “free speech”, protesters developed a way to stage the contrast between human and machine through visual aspects of language.

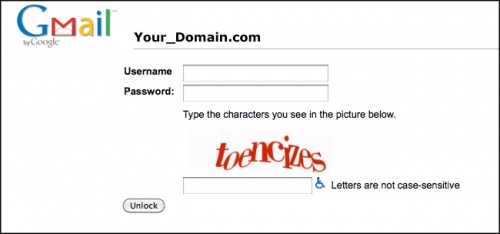

After more than fifty years, this controversial relationship finds new facets. Universally adopted as a tool to discern humans from bots, CAPTCHA -acronym that stands for Completely Automated Public Turing test to tell Computers and Humans Apart- consists of a series of alphabetic glyphs that have undergone various distortions generated programmatically. In this way the user is asked to face a problem that the machine cannot solve and spam is prevented.

For the protest movement of the '60s punch cards were a symbol of alienation, therefore the usage conversion to a system of signs understood by human beings was an act of revenge. On the contrary, CAPTCHA's function as a mean of access to the machine. The machine is now the one who judge the human nature of the user, which relates to it performing a mechanical process. There is neither ideological nor political claim in this action, it only works as a device for identification. However the circumventions of this system show how the distinction between man and machine may lead to paradoxical outcomes. Cheap labour from developing countries is hired by spammers to solve big amounts of CAPTCHA's. The visual outcome of a system of signs therefore appears as a borderline between machine and human being. Within the process of addressing the diversity between the two, their relationship is redefined and reinforced, both in a symbolic and physical way.

Punch cads punched with words, from the phonogram album cover for "FSM's Sounds and Soungs of the Demonstration!"

- Lubar, S. (1992) 'Do Not Fold, Spindle Or Mutilate: A Cultural History Of The Punch Card', Journal of American Culture, Winter, pp. 43- 55.

- Turner, F. (2006) From Counterculture to Cyberculture: Stewart Brand, the Whole Earth Network, and the Rise of Digital Utopianism.

- Wikipedia.org – Punched Card, [online], Available: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Punched_card.

- Wikipedia.org – CAPTCHA, [online], Available: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Captcha.