User:Bohye Woo/Special Issue 9: Difference between revisions

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

PAD for this semester:https://pad.xpub.nl/p/special_issue_9_pads_index | |||

= Interfacing the law 2019 = | = Interfacing the law 2019 = | ||

Revision as of 15:06, 9 July 2019

PAD for this semester:https://pad.xpub.nl/p/special_issue_9_pads_index

Interfacing the law 2019

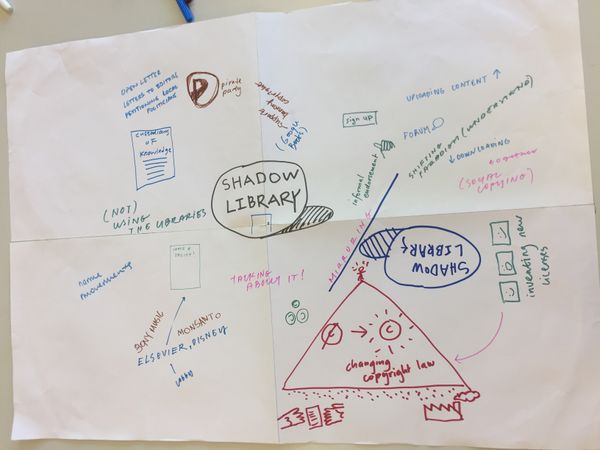

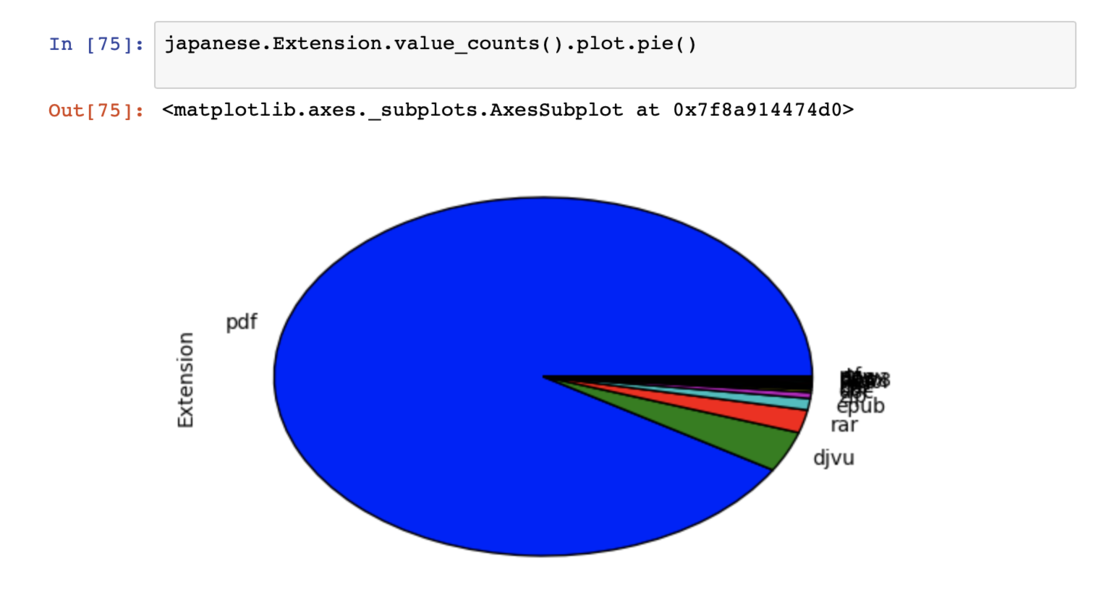

Pirate libraries, shadow libraries, piratical text collections, amateur digital libraries, peer produced libraries and how to read them together.

- Letter 1: In solidarity with Library Genesis and Sci-Hub

- Letter 2: Alexandra Elbakyan to Mr. Robert W. Sweet

- Letter 3: Dear participants in Interfacing the law!

WORKSHOP WITH FEMKE

Thursday 18 April

11:00 Intro: m-e-t-h-o-d-o-l-o-g-i-e-s (or not)

11:15 Q + Q

12:00 Response-ability

13:00 Lunch / move to Museumpark

14:00 Phenomenal cartography

15:30 s\p\e\l\l\i\n\g and/or Diffractive reading and/or Renaming|reframing

17:00 Feedback + next session

Download kit: m-e-t-h-o-d-o-l-o-g-i-e-s (or not)

Workshop with Bodo Balasz

Travel to Riedveld Library

https://pad.constantvzw.org/p/rietveld_library

http://catalogue.rietveldacademie.nl/about.html

Workshop with Eva Weynmayr

Borrowing / Poaching / Plagiarising / Pirating / Stealing / Gleaning / Referencing / Leaking / Copying / Imitating / Adapting / Faking / Paraphrasing / Quoting / Reproducing / Using / Counterfeiting / Repeating / Translating / Cloning / Silencing / Editing / Omitting / Reducing / Appending / Redirecting / Recontextualising / Focusing / (Faithfully) Reproducing / Caring / Reformatting / Bootlegging / Reframing / Retracing

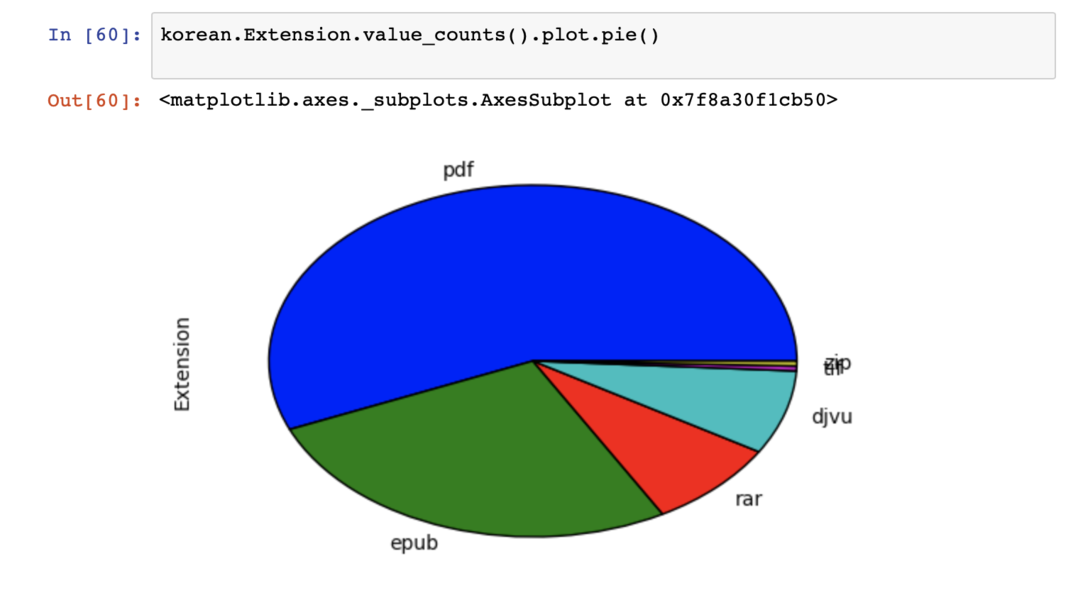

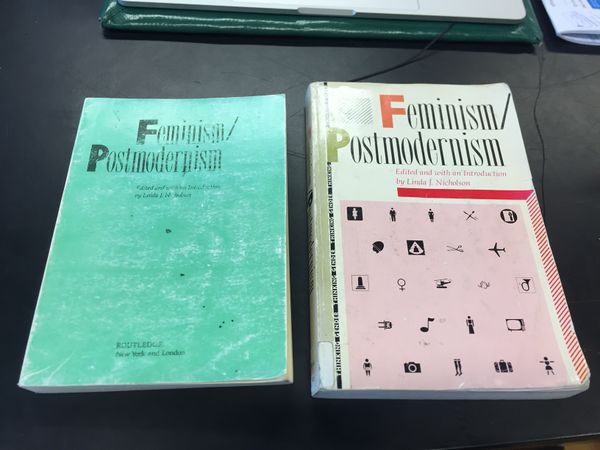

BOOK 1 — Feminism/Postmodernism

- Reproducing (but not exactly.) Producing again - not reproducing. improving materiality (imposition, bindng), adding value

- Localizing

- Crafting

This book was photocopied and assembled in a copy store, when asked by a client not imitating, or copying. the design of the cover is clearly different. it doesn't try to reproduce perfectly, or faking it. There are design decisins made. Spine writing updide down. (recultured)

What is the price of these books? What is the price of a reprodution? Original book: 35dollars, in amazon.us

- Cover

Wouldn't it be easy to photocopy the whole cover? It was a choice to only have the title and other elements, probably took more time if they had to use a paper to hide the other elements in the photocopy machine. Back cover is also very different: no information about the author, or short biography. the emphasis on the author is removed.

- Spine

Authoratitive book has title from top to bottom. Reproduced one has from bottom to top. it's crafted. (Crafting)

- Format

Printed Size, Paper, Binding are slighly different. deliberate decision: bit smaller size than A5: maybe they chose this size of their convenience for printing?

- Digital copy from LibGen:

The cover is same The contents are photocopied. There is no Back-cover.

In the authoritative copy there's a paper reminding the person who borrowed the book to put it back, this in 2004.

BOOK 2 — A Room of One's Own

- Adapting

- Caring

- Adding

- Quoting

- Inserting

- influencing

- opinioning

- bringing into conversation

- layering

- merging

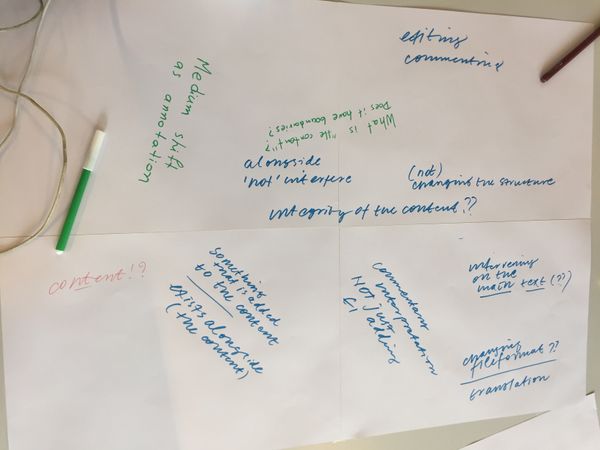

marginal notes, very simillar approach with the annotated text we were doing in Steve's class

How many people were involved?

You can see the photocopy marks.

The notes are all readable in terms of having their own space, they are not all on top of each other. How was this done? Someone designed and edited the notes, or are all the authors using the same book? Is this one book annotated by different people, or many books annotated by the owner of each copy of the book?

Very subjective vision, your reading is being interrupted by others' thoughts. The authorship is shared, collective way of reading and writing: Authorship is participative. Interdependent. You trasmit your knowledge, the reading is shared

Cover looks like Reclam publisher, but different. Just like the Feminism/Postmodernism cover of the copy, it doesn't try to reproduce perfectly, or faking it.

Workshop with Dusan Barok

Tuesday 4 June

XPUB1 Special Issue 9: 10:00 - 17:00 / with Dusan + Femke in the small project space

Workshop with Dusan Barok

10:00 Discuss launch, plans, TODO-lists (Femke)

11:00 Dusan Barok on Monoskop

13:00 Lunch

14:00 Dusan on annotation; return to plans together

note

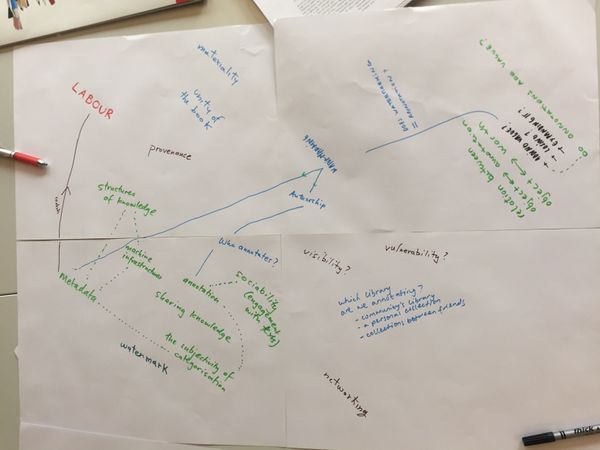

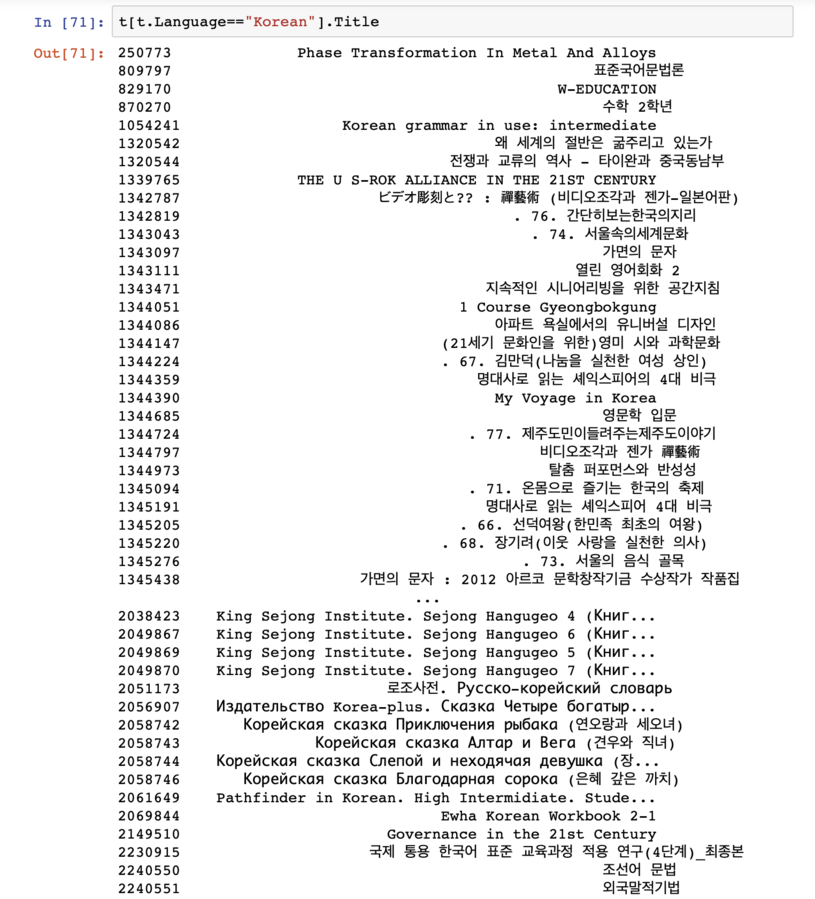

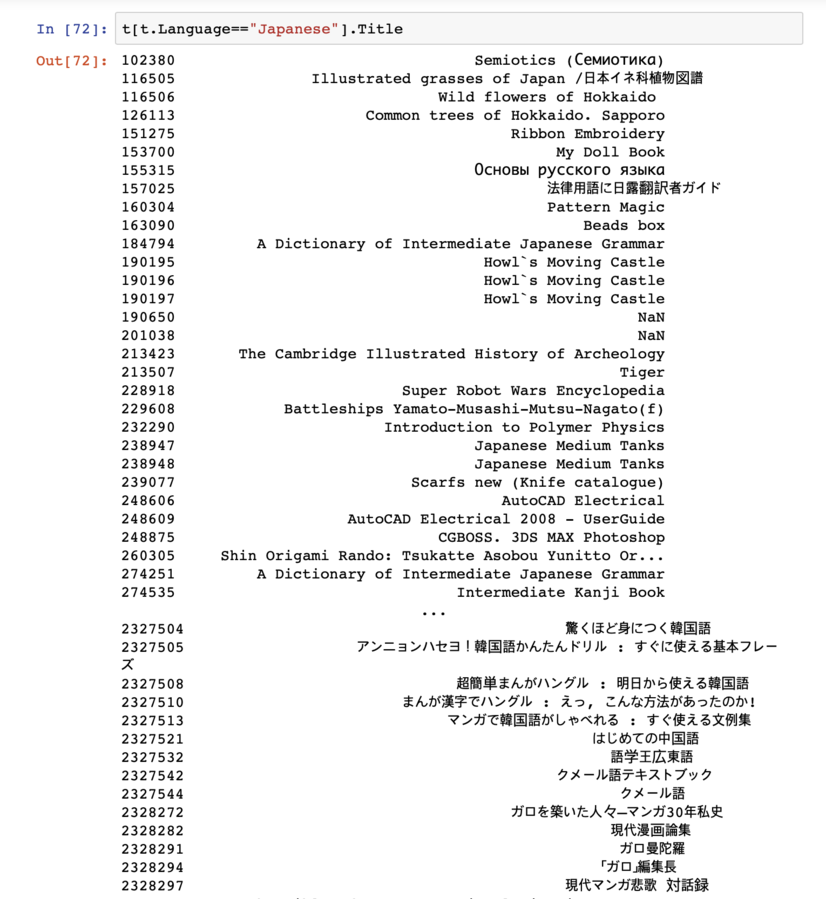

Anonymity and acknowledgment on (hidden) (digital) labor in shadow library

Authorship - economy

Subjective of categorization as a form of annotation

Labour - collectivity?

How metadata is edited in this libraries and how is the work that is behind that

Harvesting of full metadata sets from libgen for example

- Relation between authorship and work.

- Anonymity vs acknowledgment.

Story?

Thinking about authorship in the context of hidden labour in shadow libraries, I question what does it mean to possess authorship when an act of pirating is happened, how can authorship be made, what are hidden accumulated labours that we don't see physically. These labours are made by sharing, editing, scanning, modifying, downloading files, however, these materials are usually not being considered as part of 'content' as annotation, it is considered to be ignored or intentionally hidden. What, Why, and how are they hidden, how can we divulge? Do we want to acknowledge on our labour or leave it anonymously?

Method? (How to?)

— Stretching the Idea of Shadow(ing): The meaning of shadow is an area of darkness, being blocked by something, and being unofficial. And the meaning of Shadowing is a method for observing the ultrastructure of biological specimens by increasing visibility of electron microscope in order to see cells minutely. If I think of 'Shadowing' in the context of hidden labour in shadow libraries, an act of shadowing is that zooming-in the invisible layer of the library to witness traces of what is being hidden.

Workshop?

Knowledge labour in the pirate library/ Being a knowledge labourer means to download, to edit, to modify, and to upload files — finding out what labours were spent when pirating.

How?

Diving into a forensic way of investigation on labour: In order to reveal the hidden labour in shadow library, Participant will be a detective to find digital labour footages. Being in a detective mode, we'll track down traces/labours that are made throughout the process of select, copy, scan, upload, download, modify, edit, categorize files and put metadata etc...

New knowledge?

Being as a knowledge labourer, you are aware of thinking on the concept of acknowledgment on hidden labours in shadow library.

A role of annotation?

Annotation becomes a tool to acknowledge hidden labour produced in shadow libraries. It will be considered as more like a investigation(workshop) report on revealing the hidden labour.

Aim?

To experience the behind scene of what's going on in pirate libraries To be aware of legality, anonymity, and acknowledgment. To find out what possible digital labours were being hidden, and why is it important to think of? To understand anonymity in pirating and acknowledging its authorship.

Tool?

Exiftool

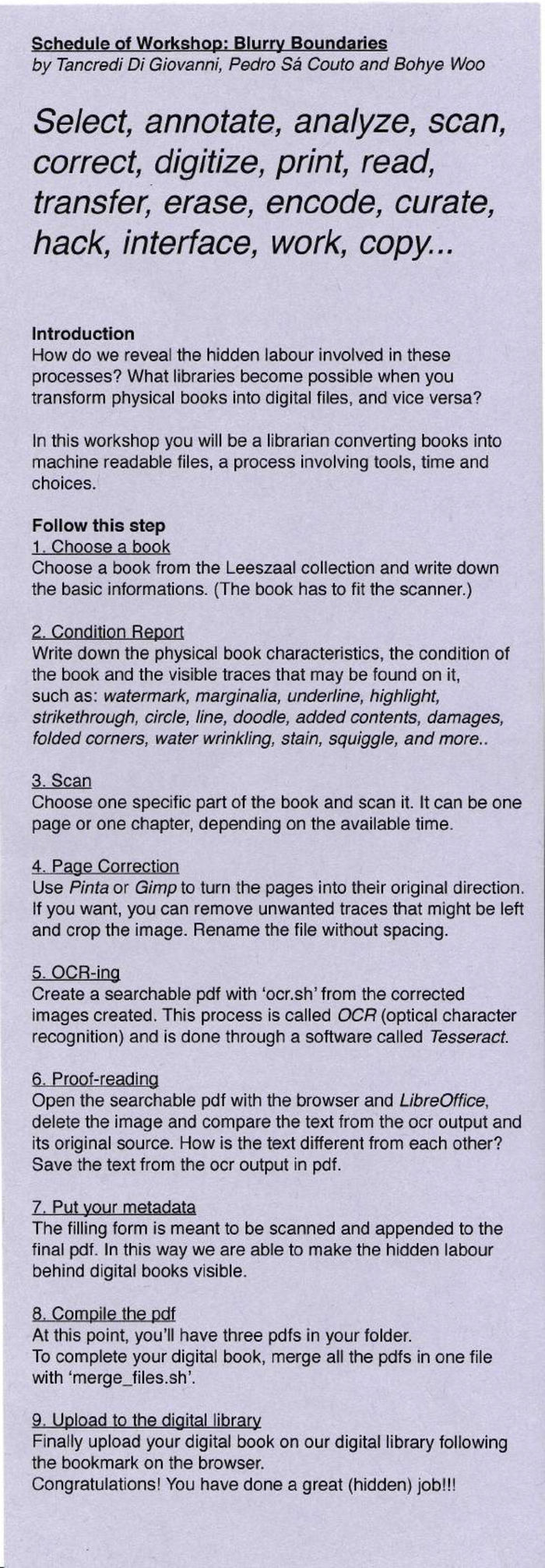

Blurry Boundaries Workshop

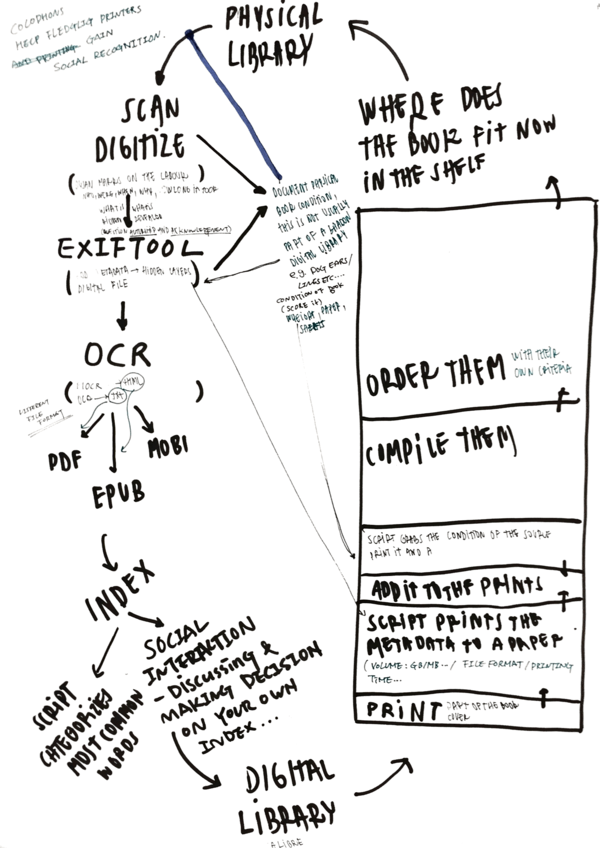

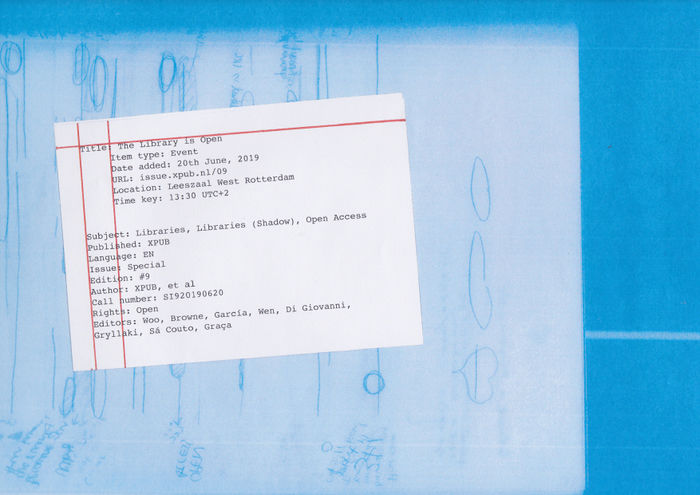

Introduction

Welcome to our {frictions, gain or loss} workshop. When one medium {physical book} is transferred to another {digital book}, situations that happen in the process are unintentionally invisible. Through the workshop, we will experience what are the steps necessary to build a phygital {physical-digital} library and reveal meticulously on what is the hidden labour and work process behind it. With this activity, we aim to reflect upon the physicality of a book when it is converted into a digital file, and vice versa. During the workshop we will question together on how we keep what is lost during these steps and how we could increase the life of the source.

Select, annotate, analyze, scan, correct, digitize, print, read, transfer, erase, encode, curate, hack, interface, work, copy...

What libraries become possible when you transform physical books into digital files, and vice versa? When a digital copy of a book is made for a digital library specific steps are followed. Each of these steps requires a decision – to use tools and to spend time. The work involved in digitising a book is invisible and the digital version often loses its connection to the physical book and the library it came from.

We aimed to reflect upon different topics such as:

the friction between the physical and digital book, what is lost and what is gained when you pass from one format to another. the physicality and contingency of these passages, the labor involved to produce those copies and its hidden position. the mindset of the librarian who has to choose how to produce the digital library, which format to chose and what kind of information to reveal. the possibility of a digital library which provides the history of the book and the people involved in its life. annotations which reveal information and challenge the common, static idea of the book.

Tools

Hardware

Computers - 4 linux/2 mac/1 win

Scanners - 2

Printer - 1 Canon mg3600 (Simon)

Software/tools

Gimp

makescan.sh (OCR>PDF)

convertpdf.sh (convert the meta.jpeg to .pdf)????

makepdf.sh (merge pdfs)

Digital Library (php uploads + directory list)

Others

- forms + condition list + info

scale papers printer's toner pens stapler bell timer

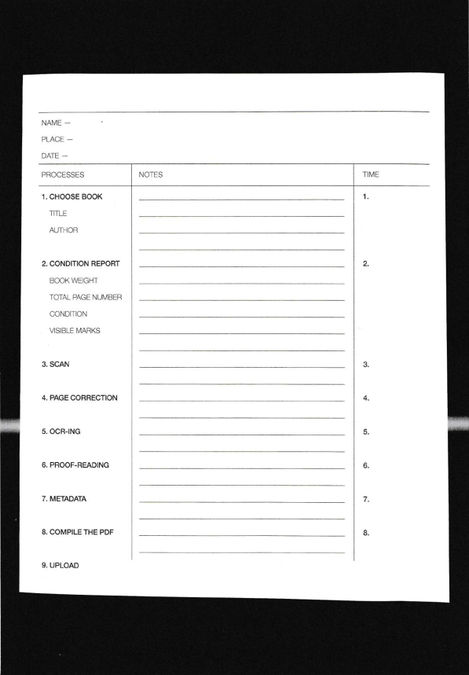

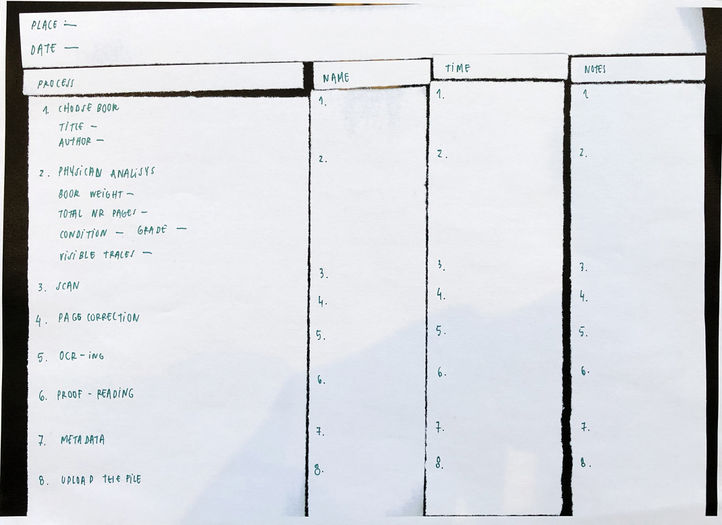

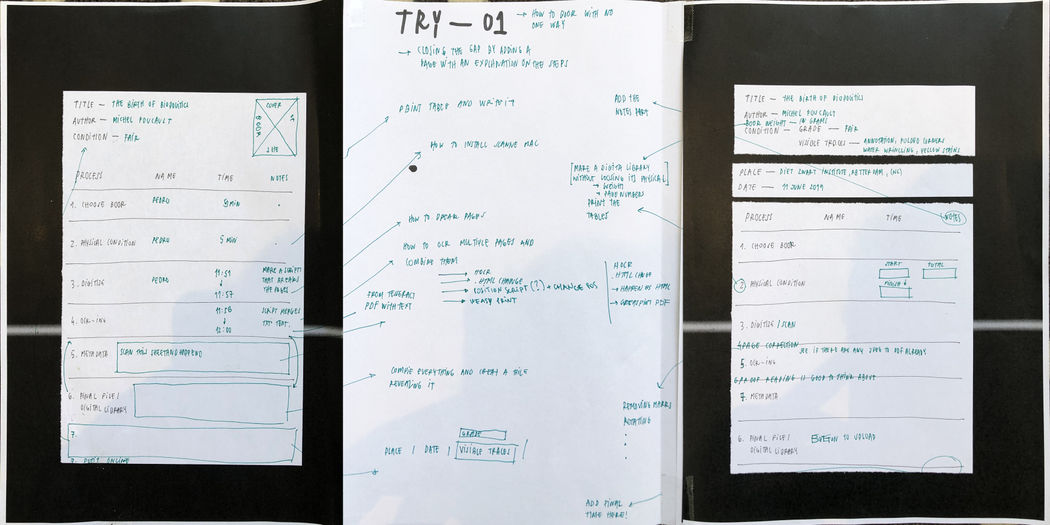

Final Labour Form

Labour form sketches

Explanation

In the papers that we are giving you, there is the hidden labour's form that you have to compile while following each step. It is important to write down the starting time of each process to notice how much time do you needed for each step. In the end we are going to scan and append it to the digital book (to produce a file with those, oherwise hidden, information of the labour involved to prduce it). The final file will contain the readable pdf, the text produced by trying to convert the scanned image into text and a copy of the hidden labour's form.

Each of you will have a computer with the main tools we are going to use on the purple sheet there is an explaination of each step to follow to help you during the process of compiling the form.

1. For first we are going to ask you to choose a book from Leeszaal, just make sure it fits the scanner.

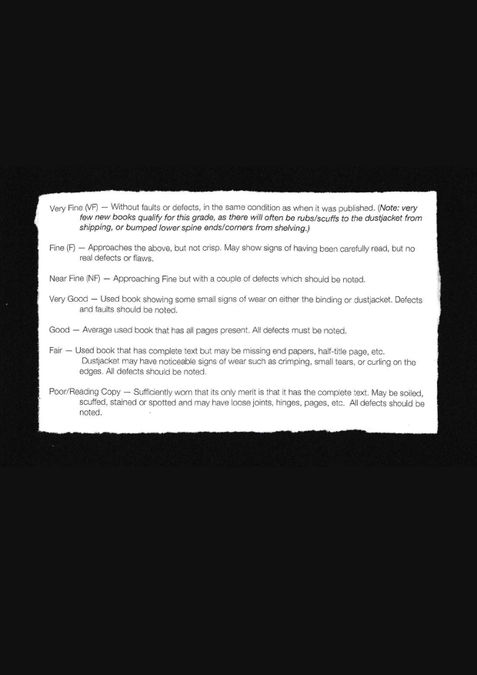

2. The second step consist in the condition report where we are going to analyze the physical condition of the book.

- There is a scale to check the weight of the book and meant to be compared with the size of the final digital file.

- A chart provided by ebay when you want to sell a book. There you can check the physical condition of the book.

- And on the purple sheet, there is a list of traces as marginalia, underlines and other particular marks that you could find on your book.

3. At the third step, starts the digitalization of the book, here you can chose one or more pages to scan that will become a .jpg image to be renamed and saved in the workshop_folder on the desktop.

To run the scanner you can run the 'scan.sh' icon in the folder.

4. Then you can open the image with Pinta (a linux version of paint) or Gimp and correct the image. For example turn it in its original direction, crop it or delete unwanted marks. Then you can save it again in the folder.

5. Now it starts the most complicate step, the translation of the image into text. This process can be done manually but actually there are softwares called OCR which optically recognize the characters in the image.

By running the file called 'ocr.sh' in the folder, the software will automatically start and convert your .jpg into a readable pdf. You can open the pdf with the browser to see how it looks like.

6. Unfortunately the ocr process is not perfect and usually needs a further step to correct it. To see what is the actual text of the ocr ouput, you can open your pdf file with LibreOffice writer, delete the image and reveal the text hidden behind it.

Then you can compare it with the original pdf and save this text in a new pdf inside your folder.

7. At this point we will use the concept of metadata, set of data that describes and gives information about other data. In fact the form will act exactly as a dataset containing your hidden labour.

To make it visible we will ask you to scan it and save it as a pdf into your folder.

8. After that you can run the 'merge_files.sh' in your folder, it will produce your final pdf that you have to rename. It will contain:

- the pdf produced by the ocr

- the pdf with the text of the ocr output

- the pdf of the hidden labour's form

9. The last step will be to print your work and to upload it in our server which you will find on the bookmarks of the browser. This small digital library that we are going to create is meant to share our works and document the workshop. It will be online in the special issue website

Photos

Post-Workshop Session - Interviewing with Dusan

Who is Dusan Barok

INTRODUCTION

Dušan Barok is a researcher, artist, and cultural activist involved in critical practice in the fields of software, art, and theory. Graduated in information technologies from the University of Economics of Bratislava, he then moved to the Netherlands to complete Networked Media masters course at the Piet Zwart Institute in Rotterdam, to finally land in a doctorate in the preservation of contemporary art in Amsterdam. He is best known for Monoskop (monoskop.org), a wiki for collaborative studies of the arts, media, and humanities, started in 2004 as a project to document and map media art and culture in the eastern part of Europe. It expanded toward arts and humanities to take its final form of a media library in 2012, as Dušan Barok's graduation project at the Piet Zwart Institute.

Monoskop is a wiki for collaborative studies of the arts, media and humanities, started in 2004 as a project to document and map media art and culture in the eastern part of Europe. In one year it expanded toward arts and humanities to take its final form of media library in 2012 as Dusan Barok's graduation project in the Networked Media master course of Piet Zwart Institute. The wiki provides an indexed collection of information, materials and links around those fields, focusing on less-known phenomena. While the parallel project called Monoskop Log, release digital books and papers to create an exhaustive archive of resources directly linked to the wiki entry. Books are available in different formats and their digitization is done by Monoskop but also users can contribute or you can find the link to the original file usually from other digital libraries.

Letter to Dusan Barok

Hi Dušan,

Thank you for your reply. We're glad that you would like to take part in our interview. Sorry that we're in a hurry but we will start the production of the publication from the 8th of this month. We were wondering what would be best for you to further talk with us. We'd like to meet you in person to have a conversation, however, we understand that it's not the most convenient period for that. So, we would like to suggest that we could either do an online video call session, or we could receive answers by email. Our questions are between the lines below, along with a small introduction about you and Monoskop that we'd like to include in our publication. If you'd like to make any changes or comments on this bio and/or our questions, please feel free to do so.

Thank you very much for your participation, and we're looking forward to hearing from you soon.

Best, Pedro, Tancredi and Bo

Reply

Hi all,

please find my responses below. Thank you again for your impulses, this was stimulating and thoroughly enjoyable. Hopefully my writing makes sense, perhaps some parts are too condensed and not clear enough.. feel free to clean the text where you find appropriate, but it's also superfine if you just leave it as it is since I guess there's not much time left. If you're thinking about images/illustrations and there's still time, I would have a few tips (mostly from the URLs included in the text) but also would be happy to leave choices to you.

Dušan Barok is a researcher, artist, and cultural activist involved in critical practice in the fields of software, art, and theory. Graduated in information technologies from the University of Economics of Bratislava, he then moved to the Netherlands to complete Networked Media masters course at the Piet Zwart Institute in Rotterdam, to finally land in a doctorate in the preservation of contemporary art in Amsterdam. He is best known for Monoskop (monoskop.org), a wiki for collaborative studies of the arts, media, and humanities, started in 2004 as a project to document and map media art and culture in the eastern part of Europe. It expanded toward arts and humanities to take its final form of a media library in 2012, as Dušan Barok's graduation project at the Piet Zwart Institute.

The wiki provides an indexed collection of information, materials, and links around those fields, focusing on less-known phenomena, while the parallel project called "Monoskop Log", releases digital publications to create an exhaustive archive of resources directly linked to the wiki entries. Books are available in different formats and their digitisation is done by Monoskop but also users can contribute or one can find the link to the original file usually coming from other digital libraries.

1. As the librarian of Monoskop, do you feel the responsibility to regularly share new files and improve how they are organised?

I use Monoskop almost on a daily basis, keeping trace of my focused or less focused browsing, reading and live encounters. A wiki, as a read-write website, really is a cool medium in McLuhan's sense. Its pages are never complete, they demand continuous updates, and being linked to one another, often it is a chain reaction, an idiosyncratic process of rereading and rewriting and following what others edited and contributed to the site. It is a messy process, by now a habit perhaps, with no end in sight, a compendium of temporary interests, passions and exchanges.

At the same time there certainly is a responsibility. The website has been part of Google and other search indexes and it does have a share in bringing people, ideas and things in focus, into attention. The responsibility here is to unveil, unearth what is not established, prominent, what is urgent, bring about new relations and contexts, burst bubbles. Our language and communication will always be narrative, a succession of signs, but we've made a long way from the primacy of a book as the basic unit of knowledge. Imagine you are not running a library but a search engine, operating in a field governed by the logic of an index and the mechanics of bots. Or that you are running a content farm, in the world where the only content that matters is either a massive dataset or a viral tidbit of information.

2. Digitising books involves decisions on how to manage human and non-human traces present in the physical book. When you select a book, do you follow any rules to manage those traces?

When scanning a book I try to enter at least basic metadata into the file, including title, author, producer, date of scanning and source of the volume. Many books I've scanned contain marginalia and highlights. I like to preserve them, which is part of the reason to scan in full color, albeit I am also aware that for some they can be distracting. They are usually personal, notes to self, rarely intended for a wider audience. Still I prefer to stay true to the original copy and its materiality.

I like to use old-school scanners for results have their own, perhaps by now vintage aesthetics. I say old-school because of course today it is more apt to use overhead scanners with digital cameras. Currently I am collaborating with artist Ilan Manouach, building a collection of conceptual comics [1], consisting mostly of works published in the past ten years. Ilan has built his own overhead scanner and photographs books with pages open, which opens up for a special physical experience. Rather than creating ready-to-print digital copies, these PDFs may be experienced on tablets and digital frames, emphasising the "visuality" of these works.

3. In the Monoskop catalog, we have found books such as "Umenie dnes" by Tomáš Štraus (for example, page 3, 158, and 172) where the digital copy contains marks from the physical source. When did this preoccupation start and what does it mean for you to explore the processes in the margins of readable sources?

This scan [2] was made as part of our "Unlimited Edition" series of digital editions of rare but important works from art history. The PDF file has coins, Czechoslovak crowns, placed on some of the pages, totaling the original price of a copy of the book. I think it was an attempt to address the relations between value, historicity and distribution. One thing is the virtue of bringing an out-of-print volume back into distribution, another is the radically different context in which this happens. The act of digitisation is often viewed as automated and neutral, but of course, as you said, there are many decisions involved along the line. One can clearly see it when comparing digital reproductions of a single volume made by different individuals and institutions. Our part is to question the logic of assembly line so tightly attached to the digitisation of art, knowledge and heritage.

4. Archives such as the Archive of the Avant-gardes in Dresden where you were involved, are starting to implement digital archives for their collections. However, the historical memory of the physical item with its time frame within a specific archive and its spatial position in it are not represented, showing a loss of criticism in the relation between materials, institutions, and people involved in its fruition. Do you think is it important to keep this historical information in the digital implementation of a collection?

It is by now well acknowledged that a printed document and its digital copy is not the same thing, their properties are different. But besides the politics of file formats and optical character recognition, there is a whole range of other issues which are subject to different affordances and interests in the digital domain. What struck me in researching the Archiv der Avantgarden (AdA) in Dresden was the palpability of contextual framework imposed by the institution of a collection upon included items, and the (however unintentional) role of the digital version of the collection to obfuscate this imposition. The archive follows, rather strictly, a certain structural logic, invented and applied to it by its original owner before the archive has been transformed into a public institution. The order has been inspired by and expanded upon the book 'Kunstismen' by El Lissitzky and Hans Arp [3] in which they represented some of the avant-garde movements of the era by various "isms". The collector had been active mainly from the 1960s through the 1980s this era obviously left its marks on the structure. You have to spend some time in the archive before the logic and structure really comes forth and gets revealed to you in full. It is very hard, if not impossible to let this happen in the digital realm. But this is where most people will access and experience it after the archive gets published online. There it won't be so obvious to notice that it almost solely represents male artists from the Western world and equally hard it will be to understand why, as this logic has also played a role in acquisitions. What kept on resurfacing during our research (there were about 60 researchers involved in the project) was the will of the AdA team to "fill the gaps". Here, a digital archive comes to help cover the traces as well. Once new acquisitions enter the archive, they will merge with the rest of the collection, as if they have always been there. A website seemingly erases the past and presents the current state of the collection as the ever-lasting one. The takeaway here is that a digital archive provides access to cultural memory but it tends to lack memory of itself; and while it provides access to world's memory, it tends to do so out of nowhere. What do we do about it?

5. Some of the books in Monoskop Log are linked to the digital library of origin; what is your intention in providing this kind of historical path of the file? Do you keep track of the viability of these links?

It is often about finding a right balance between acknowledging and protecting sources. When I am unsure I try to ask, although I am more happy when Monoskop serves really as one point in the path of a file so that one can trace it back to where it came from. Perhaps we can think of distribution along the lines of citation practises. As we said earlier, there is work and decisions involved in digitisation, and linking sources adds to both credit and accountability.

6. In your 2013 interview for the Neural Magazine you say that takedown notices are often a reality for Monoskop. Do you keep records of which books you were asked to remove, and by whom you were asked to do it? Do you think this kind of practice could reveal valuable information on how free access to texts is tracked by publishers and how to escape systematic control?

Yes we do keep records and try to be very open about it. As a rule, the entries on Monoskop Log are preserved even after the actual files are removed. I usually leave a note about the date and the subject who asked for deletion. This marks a part of the path of the book, even if it reaches a dead end in this case.

7. Monoskop explores the condition of digital books but it is a project also related to the evolution of art in its most contemporary and digital forms. In terms of your doctoral studies in the preservation of contemporary art, what is the relation between digital artworks and digital books? Should their processes of conservation and reproduction be addressed in the same way?

That's a good question, I haven't thought about it that way yet. As it happens, it is more straightforward to archive and preserve single files such as digital books in PDF and EPUB. This has been a crucial part of our work on Monoskop. However, many publications and other works are websites and similar assemblages of code and data, written in multiple programming languages with various software dependencies and consisting of many files and pages, oftentimes running on top of relational databases. Here we rely on the Internet Archive's Wayback Machine. When an online work comes down, one can almost always find its archived version on the Wayback Machine and this is what I usually do myself when I want to update a dead link to a website. I am aware there is too much at stake, and fields such as the preservation of software-based art do have much to offer here. Libraries where crawling and scraping meets emulation and virtualisation? Yes please!