User:Senka/Narrative Building Blocks

Plot

Game mechanics

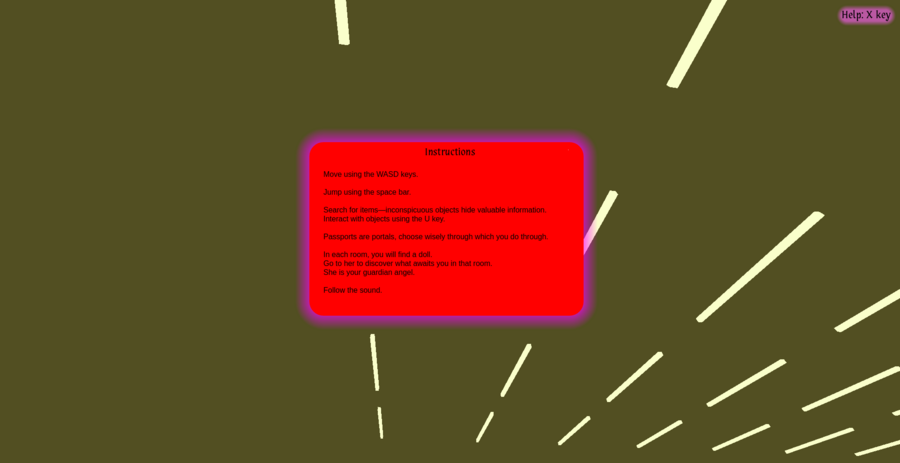

Controls

Portals

Repeating characters

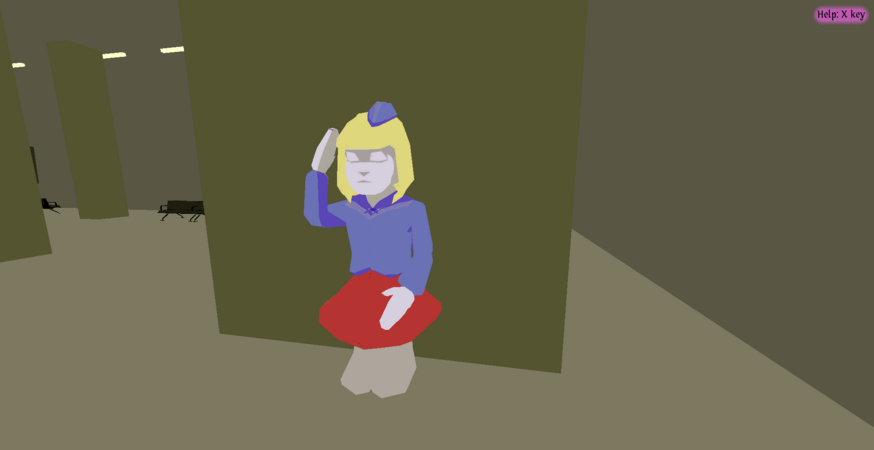

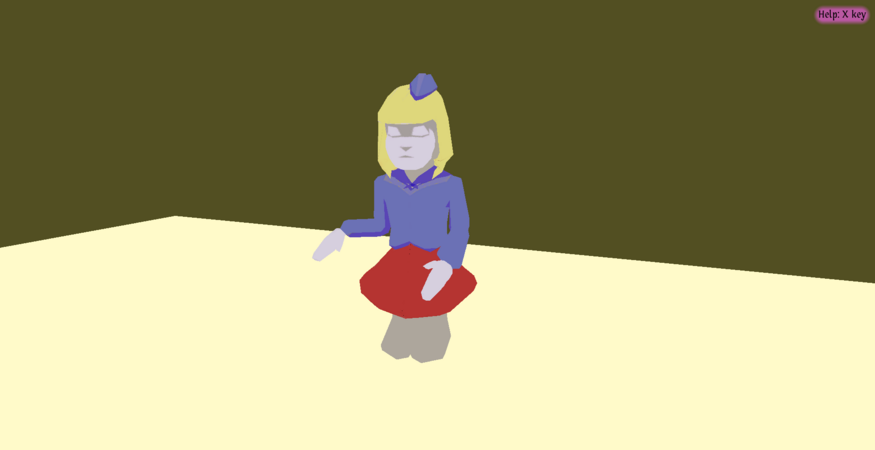

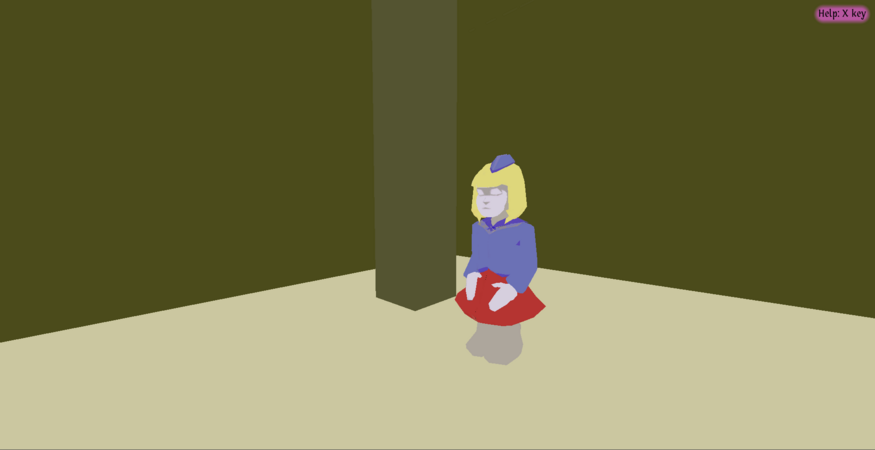

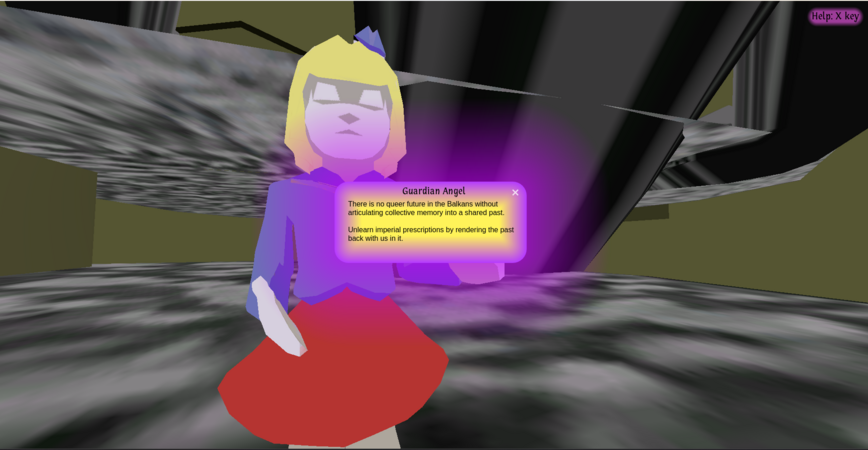

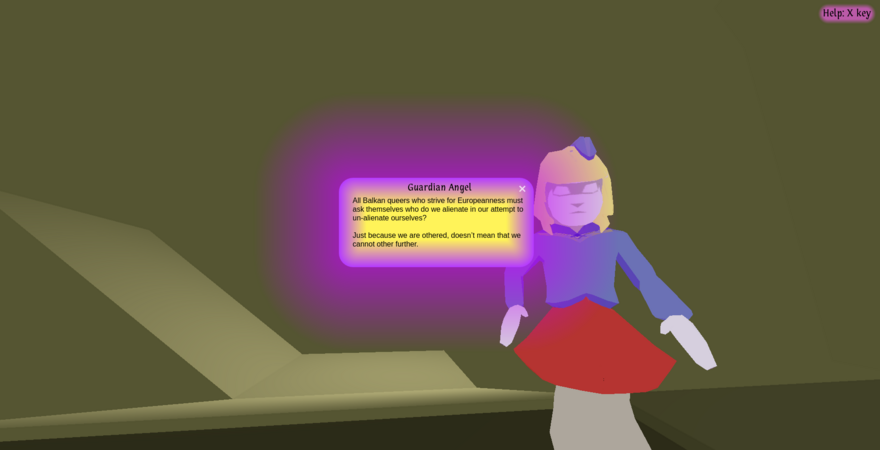

Guardian angel (placeholder name)

This is based on my doll pioneer girl keychain from former Yugoslavia (which was recently lost: sad). The keychain was getting more and more eroded as I carried her along with me: she is a testament of a rapidly disappearing history. She I haunted (like all of us).

Rooms

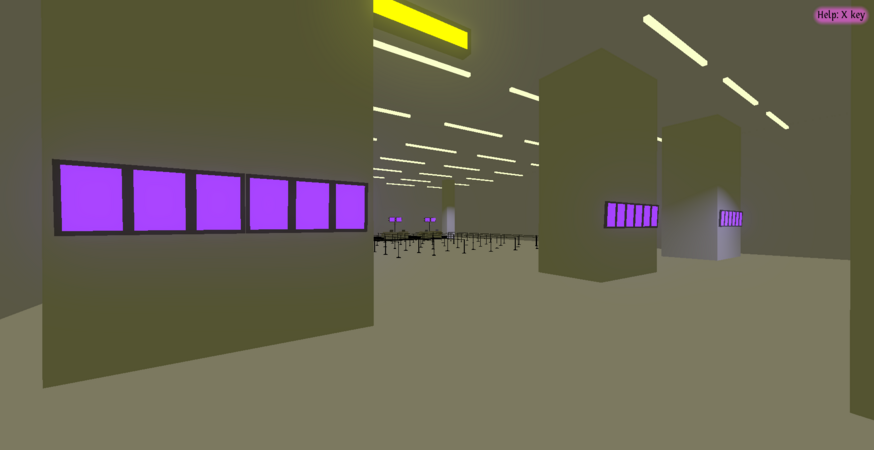

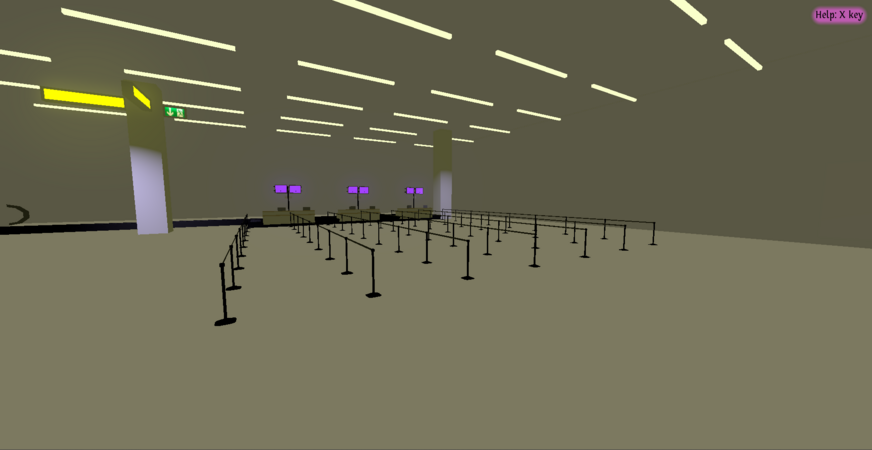

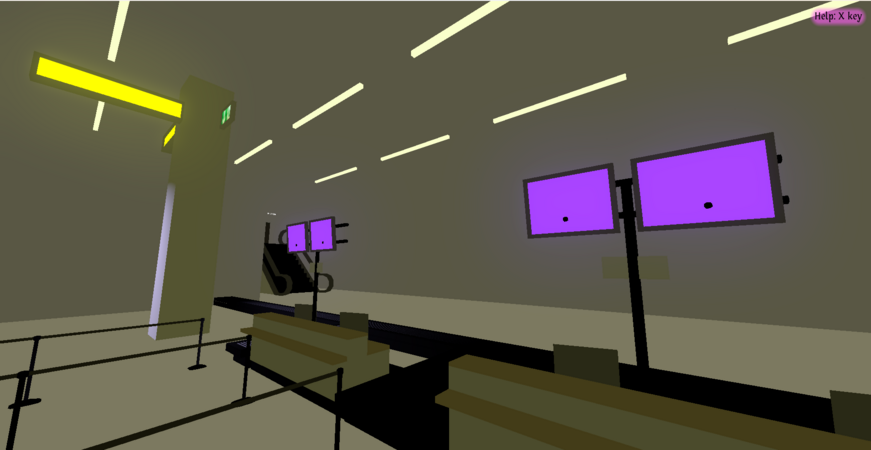

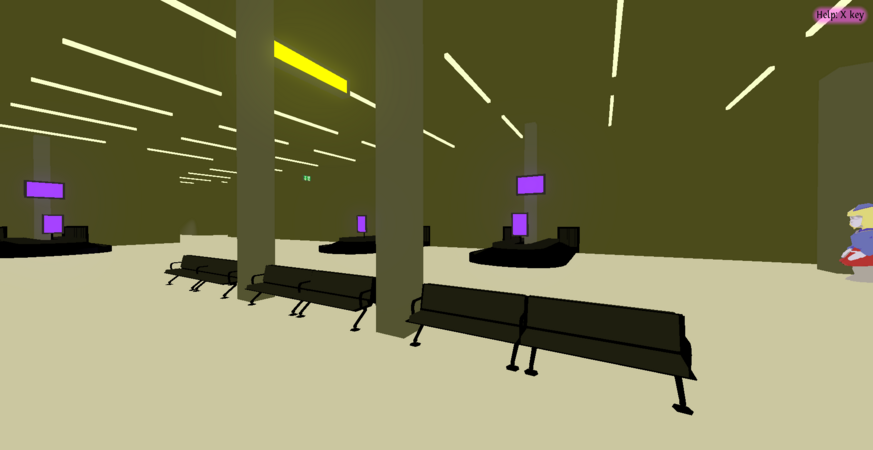

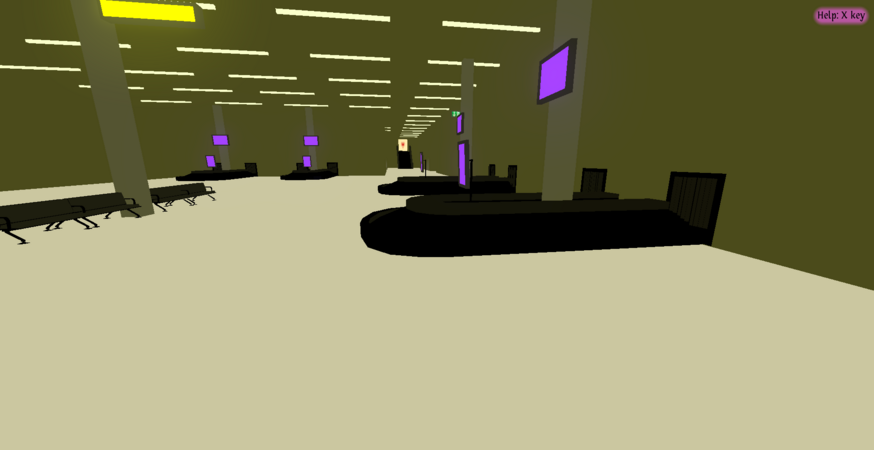

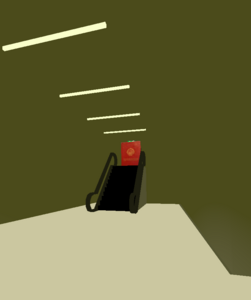

ROOM 1: Airport Baggage Check-in

3D model

Main part of departure where national and gender identity are scrutinized and policed.

Associated text

This text is straight out of the current thesis that I'm writing, it might change slightly still. Also it's missing all of the footnotes...

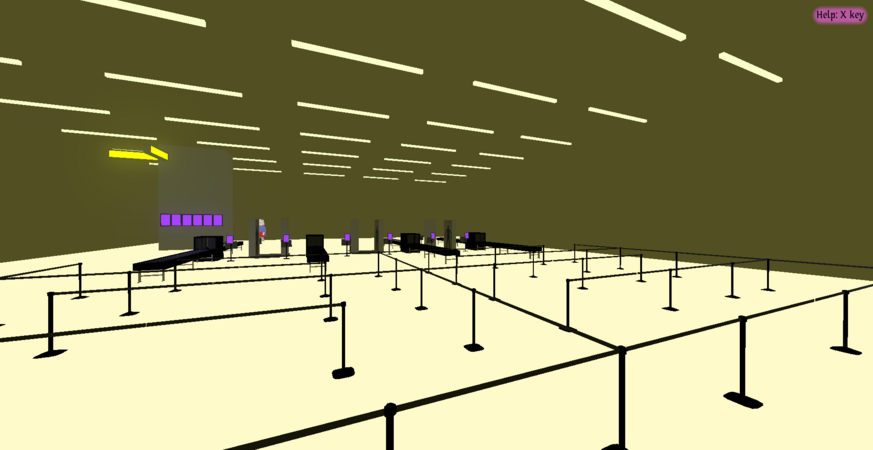

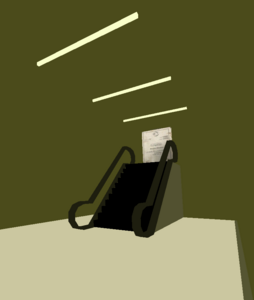

ROOM 2: Security check and Scanning

3D model

Associated text

This text is straight out of the current thesis that I'm writing, it might change slightly still. Also it's missing all of the footnotes...

ROOM 3: Baggage pick-up

3D model

Associated text

This text is straight out of the current thesis that I'm writing, it might change slightly still. Also it's missing all of the footnotes...

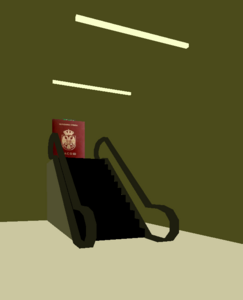

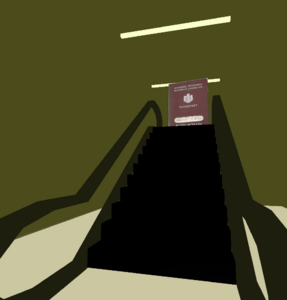

ROOM 4: Serbian Slavonic Church (14th Century)

3D model

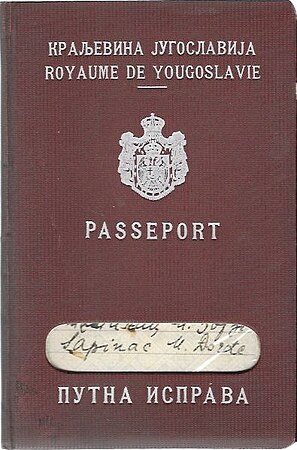

Passport

Associated text

This text is straight out of the current thesis that I'm writing, it might change slightly still. Also it's missing all of the footnotes...

When I think about you as one of my ancestors during this time, I imagine you didn’t read the script the priests held containing the prescriptions of crime, but you’ve heard about them, at the church, at home, at prayer, in whispers, in bed. You know that a man laying with another man is considered a crime, that a woman laying with another woman is a sin. That a woman taking on the role of a man is punishable, as well as any form or fashion of anal sex.11 You don’t think about the scriptures of writing that proclaim who you must be, but you strive to be this person anyway. It's hard not to project my biases onto your life. I assume that you live under the oppressive thumb of knowing that if you do not confess that your love is real (even if it is considered wrong), God will most likely still know. When you confess, you are punished without a registry, your name is not written anywhere. I do not know much about you, yet I still can’t help but keep you in my mind. Running simulations of what your life could have been. I see you looking up to the sky, looking at the trees, looking at your neighbors, seeing the God that condemned you in everyone, and still blaming yourself. I talked to an activist recently who told me that an Orthodox Christian religion teacher (вероучитељ) noted that there are church archives which have registries of same-sex unions (similar to marriages). Even though I live in the far future compared to you, I don’t expect to ever get a hold of this archival information. For me, these glimpses of light into your life remain on the level of rumour, gossip, рекла-казала. Following this thread I found this same sentiment in “Same-sex Unions in Premodern Europe,” yet I don’t know what to think about it. The author, an American gay scholar, worked on proving that some form of same-sex unions akin to homosexuality existed in medieval times. I read the Serbian Slavonic church liturgies from the 14th century, which were translated, and to a degree interpreted. In English, they talk of same-sex unions, yet in Slavonic the word братими is used. A word I understand now as brotherhood, a bond which could be a partnership, but could equaly be a friendship, a commitment to protect, or share land. I read the paragraphs asking upon the two people to kiss and commemorate the union, and I wonder whether I have any ethical ground to stand on in hoping that this was a queer practice, a step outside of the norm, a strive towards a future not set on reproduction. I remind myself, and by extention you, that „things with a past, particularly a shared one, are not as simple as they might appear from the perspective of the collector.“ |

Based on

Orthodox church inside of church

ROOM 5: Ottoman times (14th–19th or 15h–early 20th century depending on the territory)

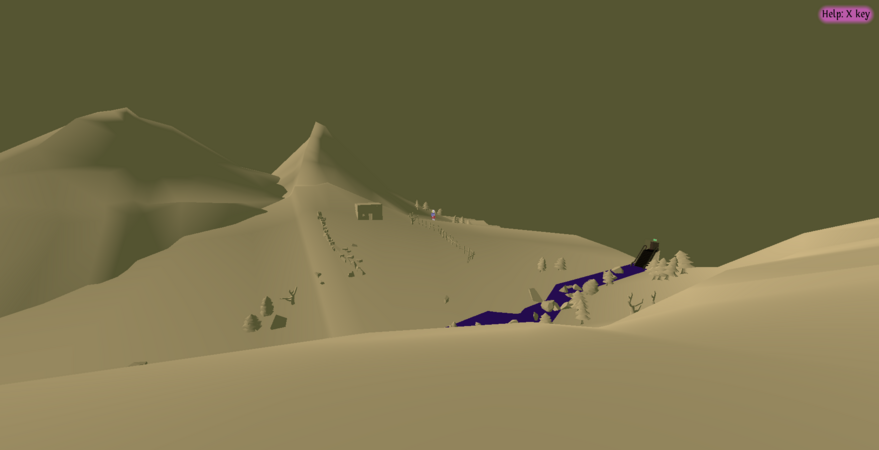

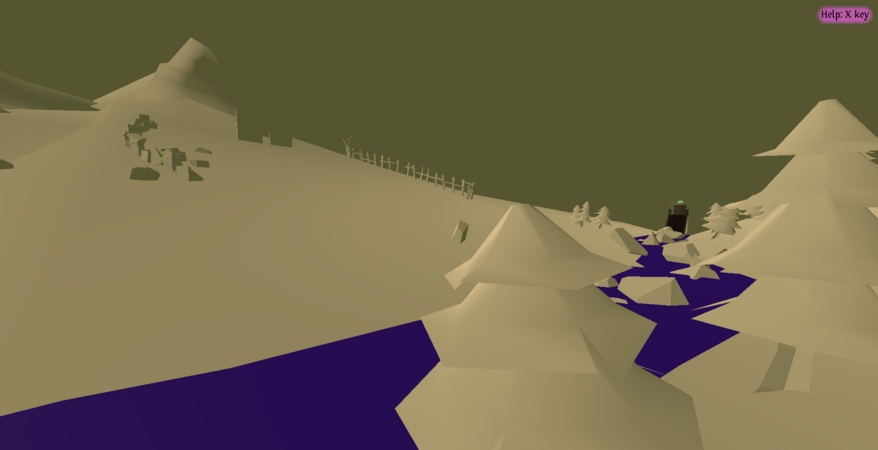

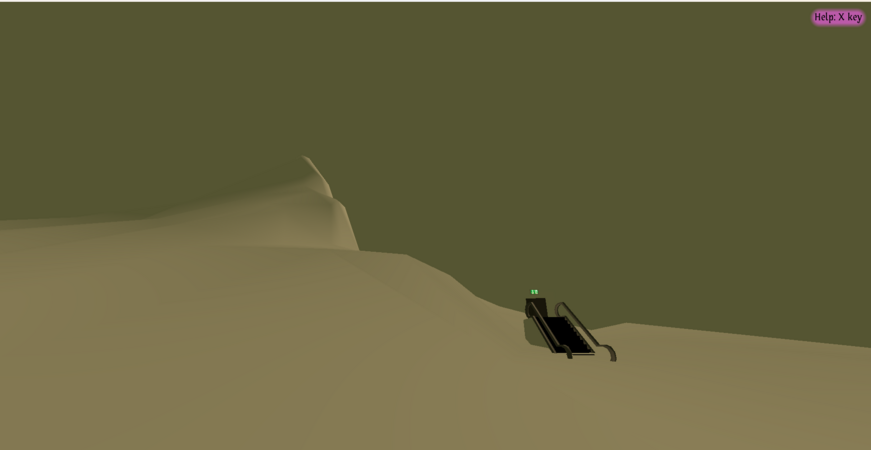

3D model

Based on

tba

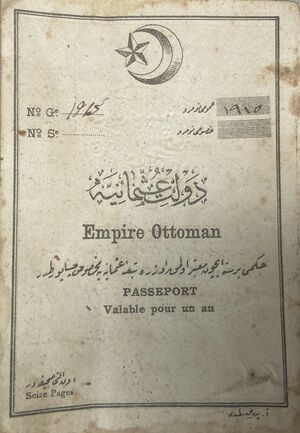

Passport

Associated text

This text is straight out of the current thesis that I'm writing, it might change slightly still. Also it's missing all of the footnotes...

You I’ve only read about in one text. Yet, I’m thinking that you’ve only heard about the acts that you do in secret, as public acts of violence, as taking over the bodies of men without question. I don’t know if you ever dared to mention what makes you feel as though you are one of them. I morph you into the history lessons I’ve been taught in primary school. I’ve never encountered you specifically on the pages, but I let myself get carried away by the thought that during winter you house all the хајдуци , freedom fighters and bandits. You sacrifice your safety for the possibility of a change. You do what you can to make up for that which you do not speak about. Admittedly, I allow myself to read into your life by assuming you might relate to those who had to hide. It is known to me, that in your time in Balkan folklore, homosexuality was ‘attributed to those who are “above” or “different” : people higher up on the social ladder, people from a different religion or ethic group, the “other”.’ The “other” here becomes the Turk, the Muslim, the “oppressor” or the “traitor”. I wonder how much you knew about this, or whether there might have been a chance that you were accepted, and that no one blinked an eye, or just said “isćefiti ti to,” meaning “try it according to your own will and liking.” It seems so clear to me that you couldn’t have known that years later, when Ivan Herzog, a psychiatrist in Zagreb, would write that decades before in the newly found Kingdom in parts that were ruled by the Ottomans, homosexuality was “quite widespread and, so to say, rather common, without encountering any opposition or moral condemnation.” |

And you weren’t the only one who lived outside of the gendered norm. Virdžine, women who have sworn virginity and socially transitioned to men existed before you, in the south of Serbia, Montenegro, Kosovo and Albania. If the patriarch of the family died and there was a lack of brothers, they, usually the eldest woman, would have to take on the role of man. And along with it of being able to go outside, down the mountainous hills, to convene and smoke with men, to work in the field, to protect and provide for the rest of the family. A myriad of previously restricted spaces were now available to them, under the pretense of giving up a future of reproduction. You, a вирџина, have to become a firm pillar of the patriarchy, you grow into old tree bark. When I look at the photos of you, I marvel at how, without hormones, the kind of life you lived has sculpted you into masculinity. Despite both of us being read in similar light nowadays—as an anomaly, a small irrelevant, forgettable statistic—you might not sympathize with me. Some вирџине, like Stana Cerović, weren’t shy about making sexist and homophobic remarks. They didn’t see anything queer about themselves. They just were. They just are. There was nothing to discuss about. It reminds me of a friend of mine saying gay, queer, unclear. How queerness deals with ‘the unspeakable, whether that be horrors of violence, loss, unrecognized forms of identity...’ |

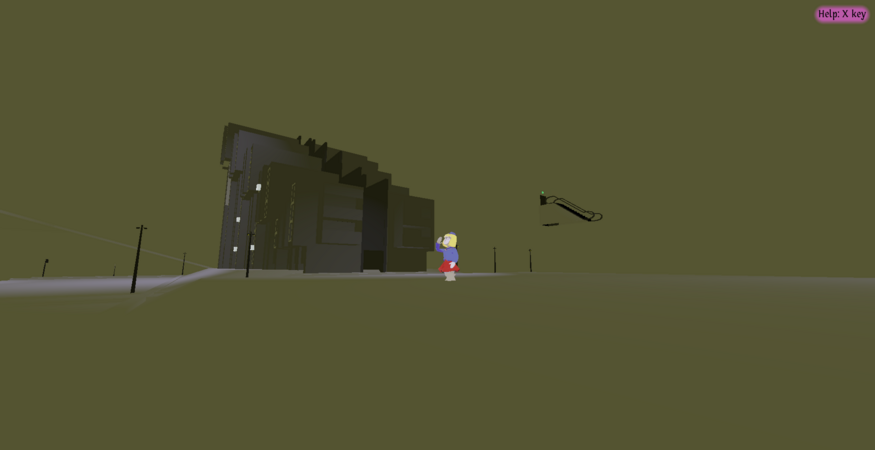

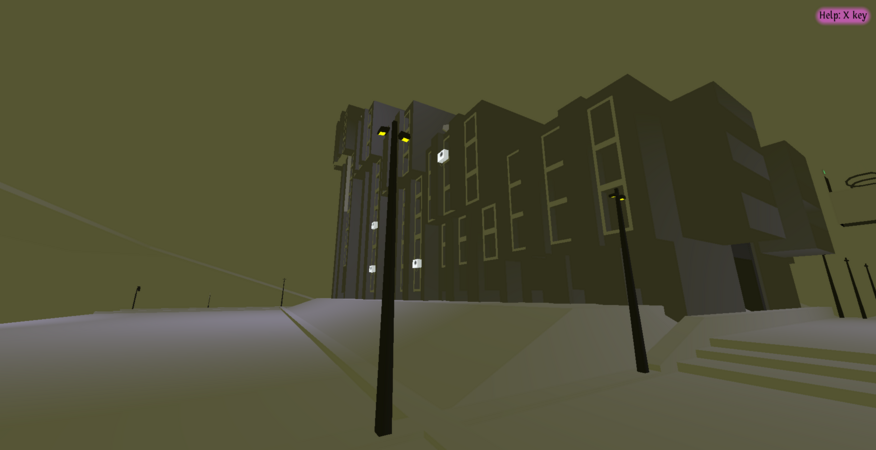

ROOM 6: The Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (Yugoslavia) (1918—1945)

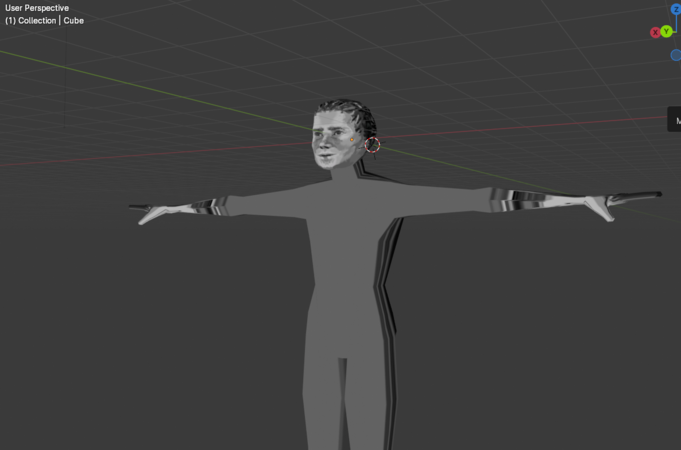

3D model

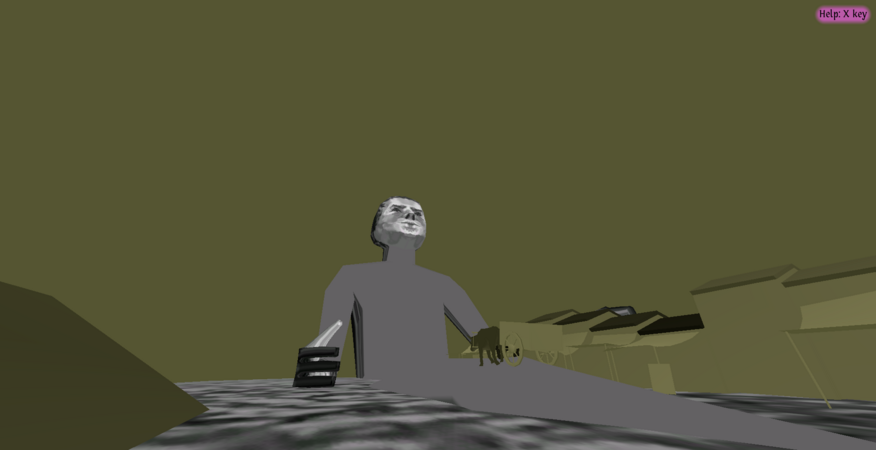

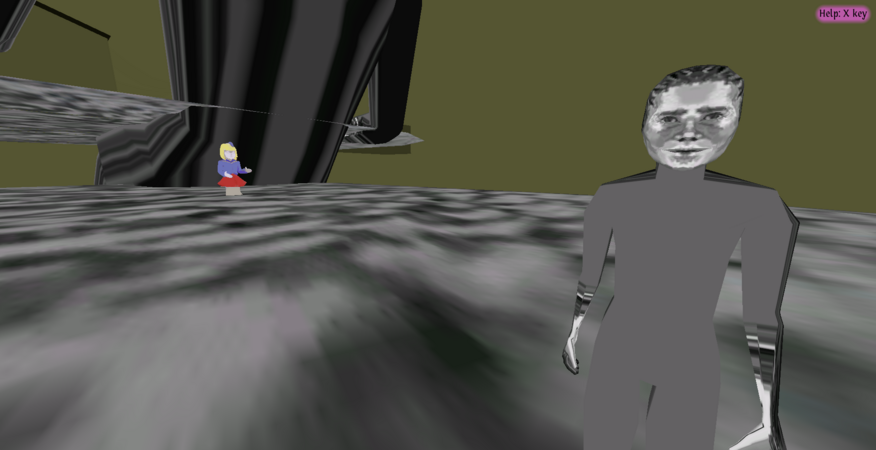

Recreated the face of the intersex/trans person from 1937 called Miloje Avramović. This is the person in a person-szied and inflated version in the render.

Based on

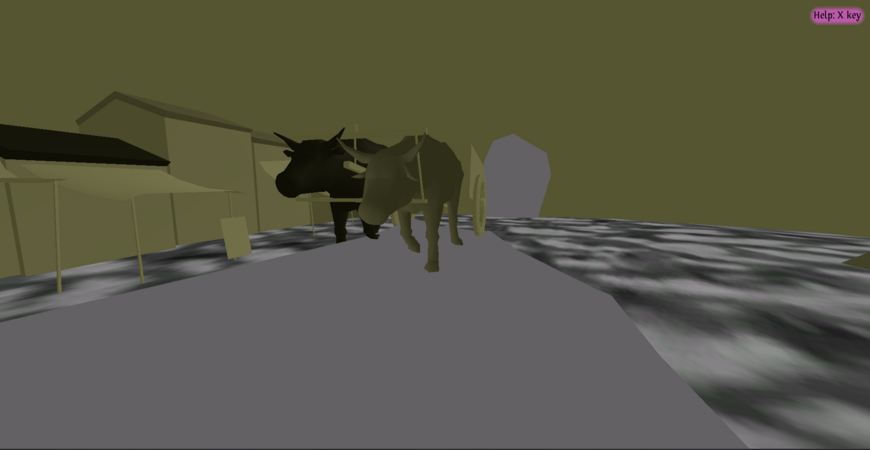

A video of Belgrade from 1922 from the Eye Film museum Archive. Link to source > [1]

And the image of the trans person from 1937.

Passport

Associated texts

You move, making way for the ox carts, quickly understanding that the farmers leading them have a whole invisible intersection of traffic lights by which they decide when and where to move. This cobbled stone feels familiar, similar to the one in the Skadarlija street in your hometown, Belgrade. Around you and your strange attire from almost a century later, walk packs of women in headscarves labouring. The city here has way more signs in Cyrillic than yours has. People still wrapped in national garments, wearing опанци and wool. You slow down to notice how many people have stopped to see the foreigners (the Dutch) holding large machinery and pointing, shooting. One of the people being recorded asks “Јел готово?”. A young boy signals he would pick a fight with the cameraman and you giggle knowing that some gestures, such as inflating your chest, have stayed the same. You observe the camera man like a hawk, how he tries to portray an image of this city as a familiar other, eastern-enough to be exotic, yet western enough to be a safe tourist destination. Yet the city is not the only thing observed under a lens—you are too. Why you? Well, you came here, to the capital, accompanied by your brothers, in search of a new body. You speak of your predicament to newspaper reporters, of how your family is helping to right the wrong nature has made of you. They’ve sold what could have been sold in your home village of Gornje Besnice to help you. The reporters follow you through all of your journey; finding a surgeon, arranging the visit, and now on the hospital bed your eyes meet the camera solemnly for a single shot, and I ask myself why your life has to be turned into a sensation. At the same time, if it wasn’t, I would not have found you either. Despite this, decades later, each person living outside of the norm of recognized gender and sex, would be treated as ‘the first’ of their kind. These same reporters, later write about how you ‘became a man’ through surgery, how you ‘cured an undeciphered sex’, how your wish was either death or unambiguous manhood. I think about the joys of childhood you’ve been denied and removed from because of your family’s shame, such as swimming with friends, dancing in коло, existing in public space. Many words used to describe you in Политика’s newspaper article, lurk in my memory, I see you accepting them as fact, without compromise, you accept ‘strange child’, ‘permanently incompetent’, ’weakly body’, ‘it’. They say nature has punished you, and suffering has been caused by your dual nature. The thought of the article being written about your search sits and eats every meal with you. And I sit with you, asking myself “How can narrative embody life in words and at the same time respect what we cannot know?” while you chew. I feel guilty for needing you and your life to speak on behalf of me, to say that we are both allowed to exist in any shape or format. But the truth is, despite the article they have written about you, probably most of your life is unspeakable. In ways that go beyond words, I am so glad you didn’t die. Imagining your trip, I can’t help but ask what Hartman asked, “How does one revisit the scene of subjection without replicating the grammar of violence?”. I note the many times the newspaper snippet switched from him to her. Academics and activists in my timeline wondered whether you were trans or intersex. From where I’m standing, nothing tells me that you weren’t both. After all, gender and sex are constructed and patched anew with each era. Yet difference, defiance, anomalies, our stubborn cells, they pop up in each of them. |

ROOM 7: SFRY Yugoslavia (1945—1991 but some countries carried the name later)

3D model

Passport

Associated texts

After your comrades find out that you are involved in homosexual acts, you get a chance to die honorably in battle. It is acknowledged that your seducer, a man from the bourgeoisie is the one to blame, and you, as a good soldier, are still allowed to die honorably. Some in higher ranks, have not been as fortunate as you have. I’ve read about you described as a “Muslim, good soldier and zealous Communist” somewhere in the region of Sandžak. Your superior, Djilas, wasn’t sure what is to be done with you as „Marx and Lenin never wrote about such matters.“ You were seen as the one who fell pray to an overindulgent class, and you had to admit to this and were expelled from the Communist party as a result. More broadly, the need to police part memebers lives and only accept spotless examples, came from the European conservative and fascist political partiy’s attempt to portray communists as „sexual offender, libertines, promoters of „free love“ and abortion, and descroyers of traditional family.“ Your leader, Josip Broz Tito, established a rule for the Party to „keep track of each members intimate conduct.“ To me, your life has never been solely your own, not under a magnifying glass, and not in the quarters of your bedroom. You as a high-ranking official working in military intelligence are ordered to die, because as a homosexual you are easy to blackmail. If there is a chance your whole life falling apart could damage the movement and the state, you need to be removed first. And fellow comrades will no longer utter your name. You start of as a radio operator, an expert in wireless transmission, steadily working towards being a “communication officer” and then later, a captain. Once it was discovered you were involved in homosexual acts, it takes three days for the General Staff to court-martial you towards certain punishment. Your name was Josip Mardešić, and you were charged with „staining the honour of all the officers of the People’s army who rightfully deserved the respect and admiration of the whole wide world“ and „abusing your rank and position to have unhealthy sexual relationships with your subordinates, and by doing so, taking advantage of their naivety and youthful innocence.“ I interpret the blurry pixels of the verdict you’ve been given, and imagine the avalanche of turmoil you must have been under to see your own life come to an end only at the age of 24. They describe your sexuality as ’настрана,’ a literal translation of which would be sidewise, not facing the proper direction. A word I, a century later, would hear this word used far too many times to describe anyone remotely queer. |

Based on

Lamela Building from Novi Beograd. Lamela building on Google Maps

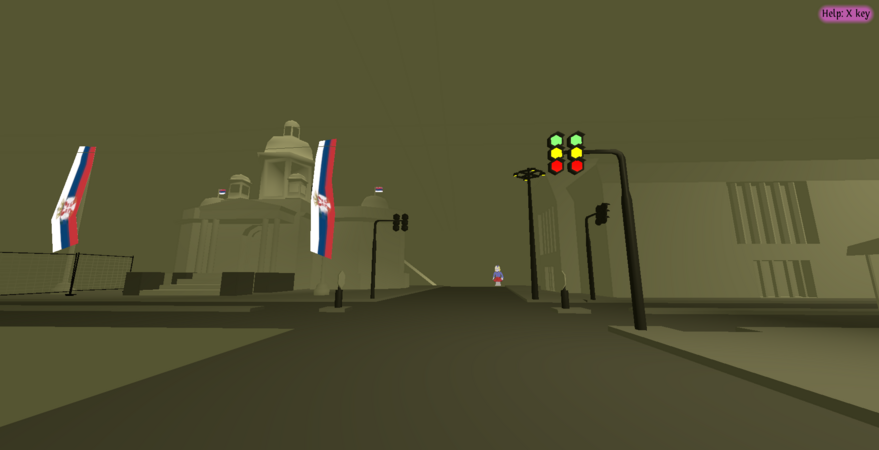

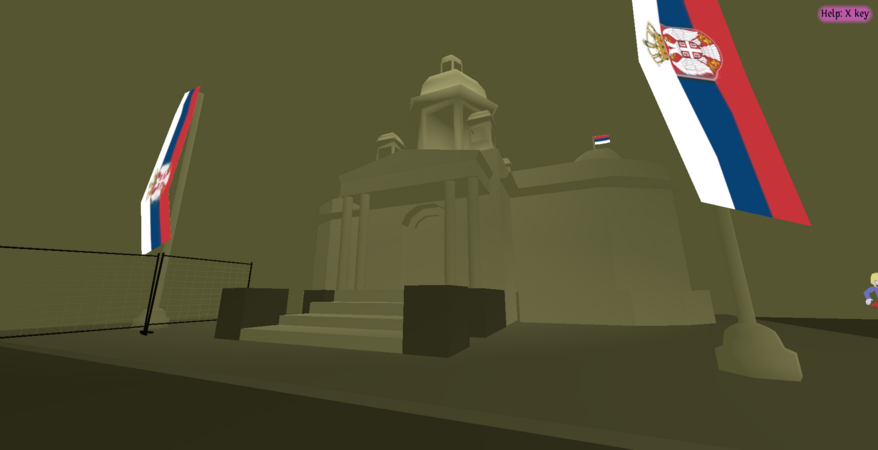

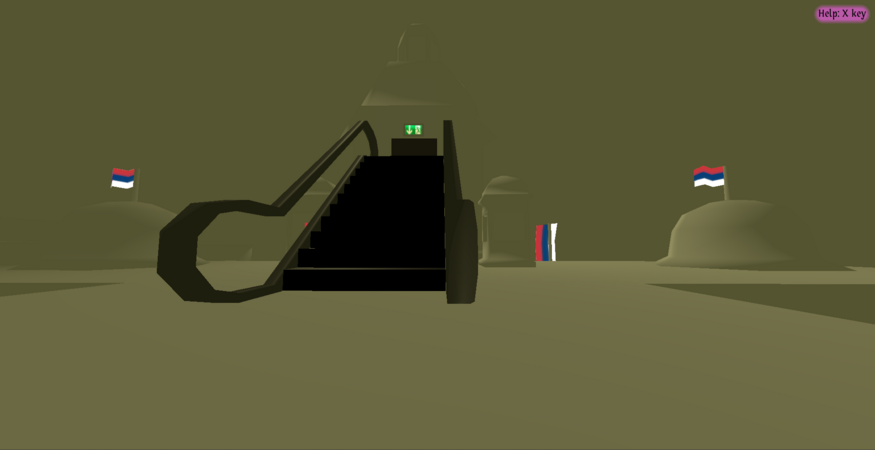

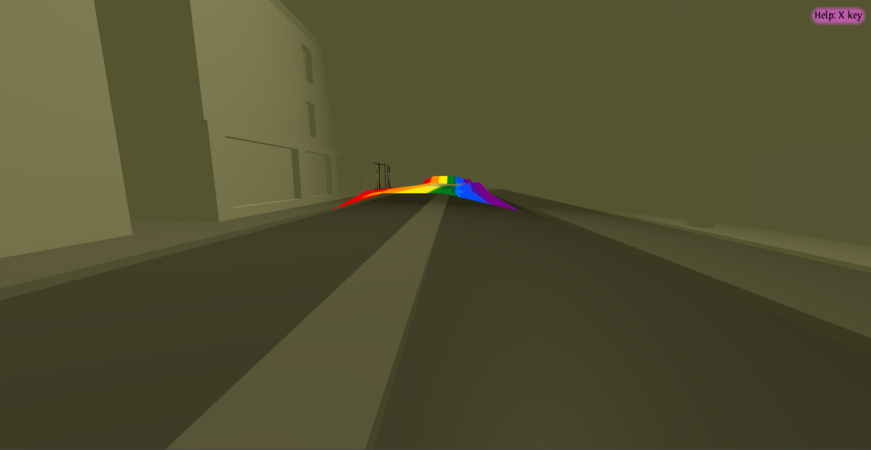

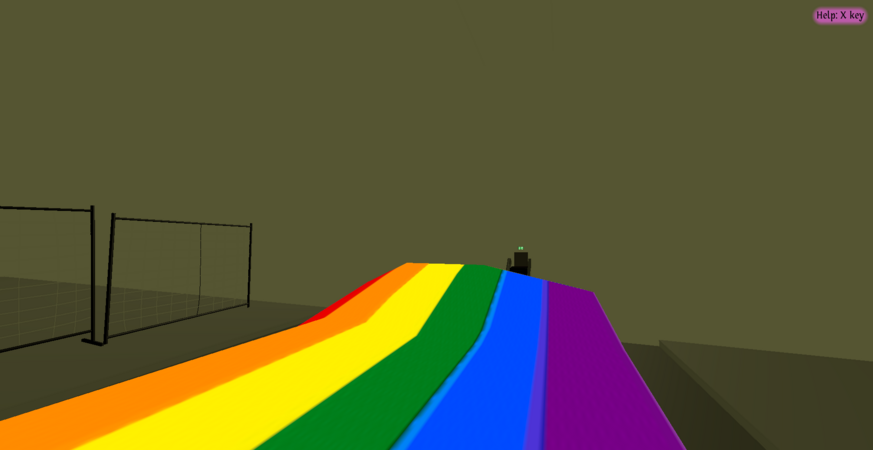

ROOM 8: SRY (1992—2003) and Serbia and Montenegro (2003—2006) up until now (accent on now)

This is the parliament building in Belgrade, and the street which consisted of the shortened pride walk for Europride 2022. The walk was shortened because of the public outrage over queer people from all around Europe coming to Belgrade. The government claimed that there was no pride walk, only people being walked to the concert by security to avoid violent incidents.

3D model

Passport

Associated texts

This placement of the text might change

You understand that in the context of the Balkan memory has been confiscated and weaponized, and a forced amnesia was in many ways mandated after the falling apart of Yugoslavia and the revitalization of nationalistic narratives. Each country needed to build its identity anew and sought to distinguish itself from its neighbors. You understand that a lot of politicians in the Balkans and Eastern Europe more largely, have propagated this idea of the “rotten West.” This notion of the rotten West goes far back, according to Marković, the youth of the romantic movement in the 19th century was already spreading the ideas that the West is tarnishing the “natural”, uncorrupted people of the Balkans. According to Marković, these ideas were not ones they came up with, but they were handed down to them by the movement of slavophiles and Oswald Spengler (a German author who wrote the popular book “Decline of the West” and a literal Nazi whose ideas influenced key parts of Nazi ideology). Slavophiles advocated for a rejection of the West and a turn towards traditional Slavic (read: Russian) values and doctrine. This means a turn away from individualism, towards collectivism, away from Western rationalism, towards Russian mysticism, and a turn away from industrialisation, towards protecting a version of the commons, were some of the ideas it featured. This ideology manifested itself in the Pan-Slavic movement, which advocated for the unity and integrity of all Slavs, and was particularly popular in the Balkans, a region which was historically dominated by an avalanche of different empires (Ottoman, Austro-Hungarian, Byzantine, Venice). Nowadays, Pan-Slavism is a divisive topic, especially after Russia’s escalation in Ukraine leading to a full-blown war. Many Slavic nations severed their ties to Russia, and by extension, to the idea of Pan-Slavism. Spengler considered one of the “high cultures” cultures to be “Western” or Faustian. There’s a range of difference now when people mention to “the West,” but it largely encompasses the territories of the Northern America, Western and Northern Europe, and Australia. The West doesn’t describe a physical border, although what gets engulphed in the West often uses borders, fences, and walls as leveraging power to keep the ”other” out. The version of West you have often heard of is the one your neighbours might bring up when they refer to you as the “European” one, on your visits back. This is something you had to read up on to make sense of and found Todorova to describe it most poignantly. She pointed the Balkans have historically been written about as a kind of borderlands stuck between east and west—culturally, economically, geo-politically. But how has this affected queer people? You know of activists in the 90s who joined the anti-war movement and waited for a better time to address queer issues. You know that certain issues, like staying alive, having a roof over your head, eating food, and not contributing to genocidal actions, take precedent. |

Kesić, the Serbian John Oliver, on his episode about Belgrade Europride 2022, highlighted (with irony) the issue of foreign queers coming to the region. He pinpoints that there was no major tension in having pride in the last few years, but now that it is a European pride, we have an issue on our hands. You remember, through foggy memory, Kesić saying: “If it stayed in the “family circle”, we would be fine, but a foreigner, worse, a western foreigner, may God protect us.” Which brings you to a question: Why is queerness seen as something inherently western? And therefore, perpetually othered, foreign, not a local problem or concern? |