User:Mania/Thesis - working document

Steve's notes

[What a GREAT START! there is a really rich mix here: your diaristic style works very well, the visual material you draw on is germane, and the references are there, without being didactic. My suggested edits are in bold and my comments are green. On Thursday let's discuss how you can bring in material from proposal, public moments, fake assessment, into the thesis (to describe project &c).]

Intro - draft

In [title] I reflect on how we perceive our direct surroundings. Perhaps we take these spaces for granted. But maybe we can learn to look at them diffrently to see those spaces as something that we make rather than discover. Through the following chapters, I delve into the tools that shape our vision, the methods that encourage spontaneous encounters inspired by the Situationists, and the role of attentiveness. Drawing insights from documentaries and early cinema I aim to uncover ways of paying attention to our surroundings.

Chapter 1 - draft

Reading the city isn’t just about observing it from a distance. The more I observed, the more I realized how complex and multi-layered cities are, interwoven with countless stories. Reading a city means being genuinely curious about its people and surroundings. It means engaging with the world and continually evolving your perception of it.

[S notes:<< you are describing a methodology for reading a city]

It involves being open to unexpected opportunities that arise IN unfamiliar streets, IN shadowed corners, IN familiar spaces, IN chaotic streets, IN the spaces in-between, IN spaces of certainty, IN neighborhood park, IN museum courtyards, IN crowded markets, IN city squares, IN quiet side streets, IN leisure spaces, IN shared spaces, IN spaces full of people, IN parking spaces, and open spaces. There are PEOPLE always in a hurry, PEOPLE who sing to themselves, PEOPLE who take detours, PEOPLE who carry notebooks, PEOPLE lost in their thoughts, PEOPLE who bike everywhere, PEOPLE who dream vividly, PEOPLE who miss their hometowns, PEOPLE who never stop questioning, PEOPLE walking alone, PEOPLE who adore symmetry, PEOPLE who enjoy getting lost, PEOPLE who love surprises, PEOPLE who stay up late, PEOPLE who speak with their hands, PEOPLE who feel out of place, PEOPLE walking slowly, and PEOPLE speaking many languages, shaping the spaces we inhabit. Perhaps we take these spaces for granted, moving through them daily withou t much thought. But maybe we can learn to see them differently: TO SEE the long way home, TO SEE the stories in gestures, TO SEE the endless possibilities, TO SEE the rhythm of the city, TO SEE the connections, TO SEE the hidden textures, TO SEE the passing time, TO SEE the absurdity, TO SEE the hidden shortcuts, TO SEE the unexpected, TO SEE the structures, TO SEE the stories, TO SEE the choices in how we move, TO SEE the city’s edges, TO SEE the city as a game, TO SEE hidden playgrounds, TO SEE new paths, TO SEE the extraordinary in the ordinary, TO SEE the absence, TO SEE with the greatest precision, TO SEE what’s written in the street. When we learn to see, nothing will stop us from reimagining these spaces anew—other uses, other functions, other possible ways of navigating them. I believe the first step is to pay attention.

It started this summer, with a pair of binoculars I bought at a market for three euros. Totally absorbed, I spent hours on Yana's balcony, observing the rooftops of Sofia — textures, antennas, and edges. Gradually, fragments of the city revealed themselves. Serendipity played a role in these observations, and I couldn’t have been happier, as I noticed things that usually go unnoticed. The binoculars became my tool for "reading" the city and found a permanent place in my routine. [How so, it would be interesting to describe the experience of seeing anew through this new "lens". Please describe a particular moment. What is happening? The reader can then share the immediacy of that experience] I became obsessed. Through them, I observed Sofia, Warsaw, Frankfurt-Oder and Słubice, Rotterdam, and Groningen. It fascinated me how even the simplest tool, with its inherent limitations, could open us to unexpected opportunities. How narrowing the field of vision, allows for looking at the city piece by piece and brings a specific fragment to the front.

I built a camera obscura, large enough to step inside and place it in public space. I was curious to see how our perception changes when we view an image upside down. Would we notice something extraordinary in what we see every day? Unfortunately, the costs of constructing such a device overwhelmed me. Instead, I realized this idea within the confines of my room. Using cardboard and the properties of light, I transformed my room, already positioned on the street, into a camera. I darkened the entire space, leaving a pinhole to create an inverted image. On my table, I saw a fragment of the bridge where train tracks once ran. At that moment, I knew I was inside the camera. The projection was smaller and blurrier than I expected, yet I observed the bridge fragment with a level of attention I’d never given it before. For two years, that view had been the first thing I saw when opening my door. It wasn’t until I saw it upside down that I truly paid attention. [where did you make this?]

I continued observing my surroundings. For days, I sat in a square, observing at specific times. I watched my street through the frame of my window. I observed the street corner framing it from a café. I built a device — a tube – for reading the city. I watched the city through a paper frame, a camera, and a film camera lens. I became an expert observer.

But do we really need tools for this? [The other question is: what do you gain from using such tools? Why is it satisfying for you to frame? What happens when you crop? What happens when you frame?] Isn’t curiosity and simply being in a space, observing what surrounds us, enough? Devoting time and attention seems sufficient, yet so much escapes us and remains unnoticed. We cannot take in the entire city at a glance; we need separation and pauses to interpret what we see. Otherwise, everything becomes a continuous stream of unprocessable information. What matters to me is how this observation can contribute to our active participation in a space. It is in this context that I want my magazine to become a frame for urban observations and situations. And thats also what I mean by a tool.

I decided to narrow my focus, choose a fragment, and frame it for closer examination. Inspired by Alison Knowles's 1967 poem The House of Dust, [<describe that text in a sentence or so] I developed a script to list various locations, people one might encounter there, and observations. The script randomly combined entries from each category, generating statements that I treated as prompts for further focused observation. [Note: With the script, you are creating another technology for looking (like the camera obscura, binoculars and tube). It seems to be different to mapping a space. It is about apprehension of a space, more than about its relation to other spaces. Are these devise about providing an encounter with a particular space? It is interesting how the aesthetic that is developing mirrors early film and photography. What do you think the relation is, for you? (there are no wrong answers here).]

Thus, the first issue of Fragments Magazine is dedicated:

FOR PEOPLE who always carry a notebook

TO SEE the choices in how we move

IN open spaces

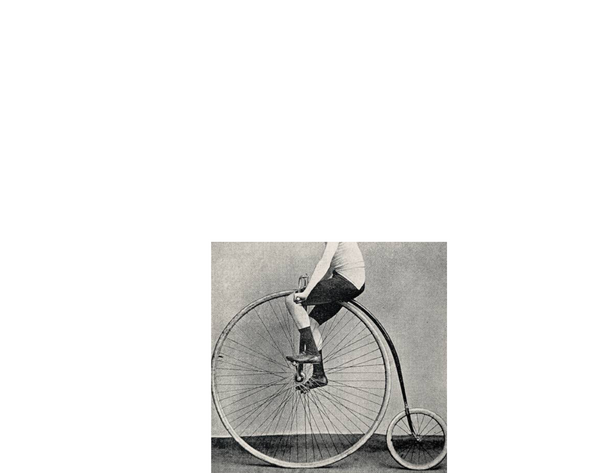

(I searched for photographs in archives and video materials from early cinema because I wanted to work with these fragments. I wanted to use cropped images to illustrate the choices in how we move, and I got lost in a sea of colorful frames from Scheveningen in the Twenties.)

- ↑ The Production of Space, Henri Lefebvre

- ↑ Silent City Films (early 20th Century): https://library.fiveable.me/city-in-film/unit-2/silent-era-city-films-urban-modernity/study-guide/uxbdekHKTNFoe9U4

Outline

Chapter 1

What does it mean to read the city? - Part 1

Tools for reading the city - Part 2

- The Production of Space, Henri Lefebvre

- Smooth City, René Boer

- Creative Processes in the Human Environment

Chapter 2

Methods for spontaneous encounters - Situationists approach and the art of chance

- The term "society of the spectacle”, introduced by French theorist Guy Debord in his book The Society of the Spectacle, describes a society influenced and dominated by images, advertising, and media, where appearances are more important than authentic experience. Following this thought I would like to dive into "Report on the Construction of Situations" by Guy Debord (1957). In this manifesto, Debord explains the concept of "constructed situations" encouraging interventions in urban spaces that provoke new ways of seeing and interacting with the city.

- This chapter is a space for critical reflection on how I can activate the magazine in public spaces.

Chapter 3

Scripts or unintentional adventures? - What documentaries taught me?

- In this context, the book Why I Make Documentaries by director Soda Kazuhiro is especially important to me. In it, he discusses observational filmmaking, speaking about rejecting the idea of preparing a script before shooting and instead creating a story based on discoveries that happen during the process. He also talks about the unexpected discoveries, encounters, and unintentional adventures that the observational filmmaking approach brings. I agree with not strictly adhering to a script, as it’s so easy to cut out even the most interesting scenes simply because they don’t fit a narrowly defined topic. On the other hand, I believe that a script that remains open to interpretation can actually enhance imagination and open up new ways of exploring public space. I believe that scripts and unpredictable encounters can complement each other, and I’m curious how I could explore this further.

- There was this film that I saw during the French film festival - where two characters decided to walk always in a straight line —- so they had to walk on top of the car cause it happen to be on the way.

Chapter 4

Cutting, fragmenting, rearaging - as a way of rewriting our spaces

- Dziga Vertov – Man with a Movie Camera (1929) - This documentary film captures a day in the life of a Soviet city through the eyes of a "movie camera man.” There is no one plot, the film maker is experimenting with montage techniques. Vertov’s approach presents the city as a dynamic, interconnected system.

- Drawing from these examples I will reflect on my practice, which incorporates image-making. I still record and photograph a lot, but then I use this footage to translate it into a collage. fragmenting and rearranging as reimaging. A lot of this happens in my notebook

Intro

With this paper, I dedicate time to moving through various places and observing them with curious eyes. It brings together fragments from my notebook, making the writing a dialogue with walking, collecting, and rearranging fragments. This text is an opening to the unexpected, to accidental discoveries and observations. I aim to uncover alternative ways of seeing and relating to our cities. I seek ways to open to different experiences, searching for unpredictability and surprises in the city, exciting connections, and interactions with others in shared spaces.

Chapter 1. What does it mean to read the city? - Part 1

Reading the city isn’t just about observing it from a distance. Reading a city means being genuinely curious about its people and surroundings. It means engaging with the world and continually evolving your perception of it. The language of the city lies in the situations and unexpected opportunities that arise. We read it with our eyes, ears, and feet

IN unfamiliar streets,

IN shadowed corners,

IN familiar spaces,

IN chaotic streets,

IN the spaces in-between,

IN spaces of certainty,

IN neighborhood parks,

IN museum courtyards,

IN crowded markets,

IN city squares,

IN quiet side streets,

IN leisure spaces,

IN shared spaces,

IN spaces full of people,

IN parking spaces, and open spaces.

There are

PEOPLE always in a hurry,

PEOPLE who sing to themselves,

PEOPLE who take detours,

PEOPLE who carry notebooks,

PEOPLE lost in their thoughts,

PEOPLE who bike everywhere,

PEOPLE who dream vividly,

PEOPLE who miss their hometowns,

PEOPLE who never stop questioning,

PEOPLE walking alone,

PEOPLE who adore symmetry,

PEOPLE who enjoy getting lost,

PEOPLE who love surprises,

PEOPLE who stay up late,

PEOPLE who speak with their hands,

PEOPLE who feel out of place,

PEOPLE walking slowly,

PEOPLE speaking many languages,

shaping the spaces we inhabit.

We often take these spaces for granted, moving through them daily without much thought. But what if we could learn to look at them differently:

TO SEE the long way home,

TO SEE the stories in gestures,

TO SEE the endless possibilities,

TO SEE the rhythm of the city,

TO SEE the connections,

TO SEE the hidden textures,

TO SEE the passing time,

TO SEE the absurdity,

TO SEE the hidden shortcuts,

TO SEE the unexpected,

TO SEE the structures,

TO SEE the stories,

TO SEE the choices in how we move,

TO SEE the city’s edges,

TO SEE the city as a game,

TO SEE hidden playgrounds,

TO SEE new paths,

TO SEE the extraordinary in the ordinary,

TO SEE the absence,

TO SEE with the greatest precision,

TO SEE what’s written in the street.

When we start to look at them differentky, nothing will stop us from reimagining these spaces anew and other possible ways of navigating them.

In cities, there are far more unexpected connections than one might think. But sometimes, noticing them takes time. Waiting for the unexpected to happen might seem boring to some people. When we set out to find it but fail to see it, it can frustrate us. However, waiting in this context is important. Waiting is a part of reading the city. By waiting, we allow ourselves to get bored—and that boredom can lead to unexpected, creative ideas. Waiting is a resistance against efficiency at all costs. Reading the city isn’t always equally exciting. Reading the city requires time and attention. It involves getting lost, observing in the rain, or taking the long way home. Not everything has to be productive, smooth, or predictable—and that’s what makes reading the city so fascinating.

René Boer’s concept of the “Smooth City” ties into this idea. He describes the growing tendency in urban environments where experiences become increasingly seamless. We have services that deliver groceries to our doors, dating apps, and smart solutions that provide us with comfort, but they also create a frictionless environment. While everyone deserves a safe and clean environment, such conditions gradually eliminate opportunities for serendipity, potential, encounters, and all those unexpected events that cannot be planned in advance. This raises an important question: what kind of cities do we really want? Do we prefer a predictable, frictionless environment, or do we want to embrace random chances? Personally, I long for a city where I can be myself, where I enjoy conversations with strangers, where I discover new paths, where not everything is reduced to the same ideal, polished appearance—a city created by people and therefore full of potential.

This magazine may seem a bit messy, but this messiness in unpredictability can bring unexpected connections. And this is what the act of making this magazine public and publishing it outdoors call for. It seeks to decode the language of the city and by actively existing in public space, it becomes a tool for that, knowing that this act is an unfinished process. The image of the city is ever changing, its never complete.

To focus this exploration, I decided to narrow my scope: choose a fragment and frame it for closer examination. Inspired by Alison Knowles’s project The House of Dust, in which she used code to generate short poems that she later translated into physical houses, I developed a script, listing various locations, people one might encounter there, and observations. It then randomly combines entries from each category, generating statements that I treated as prompts for further focused observation.

Thus, the first issue of Fragments Magazine is dedicated:

FOR PEOPLE who always carry a notebook

TO SEE the choices in how we move

IN open spaces

I think that limitation and a certain imposed boundary can be very creative. Through the script, which selected and combined three entries from a wealth of street observations, a relationship between them emerges. And in a way, this automatically opens up new possibilities. This was initiated by the computer, but what happens next depends entirely on my interpretation.

Tools for reading the city - Part 2

As much as I am captivated by the moving image, cities are not only visual. Like Lawrence Halprin wrote: “Architecture alone does not make a great street anymore than a fine stage set makes great theatre. The two depend, finally, on what happens and what interactions occur; what they generate in the human experience” (‘Creative Processes in the Human Environment’). In this context I'm interested in how even the simplest tools, which impose certain limitations, can open us up to unexpected opportunities.

I’m curious about translating what film works with into a system for exploring physical space. Film deals with scripts, continuity, speed, time, rhythm, and frames. They use cutting and rearranging pieces. I’m curious to use these elements as tools for decoding the language of the city. I want to allow an interplay between what is perceived and what can arise and come into view.

This fascination with framing started this summer, with a pair of binoculars I bought at a market for three euros. Totally absorbed, I spent hours on Yana's balcony, observing the rooftops of Sofia—textures, antennas, and edges. Gradually, fragments of the city revealed themselves to me. Serendipity played a role in these observations, and I couldn’t have been happier, as I noticed things that usually go unnoticed. The binoculars became my tool for reading the city and found a permanent place in my routine. With a newfound interest, I scanned buildings, gliding along their lines. They made me notice houses that look like they are hugging the one in the middle. Passersbys entered and exited my frame, suddenly, the city became full of surprises. I became obsessed. Through them, I observed Sofia, Warsaw, Frankfurt-Oder and Słubice, Rotterdam, and Groningen. It fascinated me how even the simplest tool, with its inherent limitations, could be an opening for so many surprises. What I mean is all th ethings I have seen before but ignored. I find it intresting how narrowing the field of vision, allows for looking at the city piece by piece and brings a specific fragment to the front.

Inspired by that, I decided to build a camera obscura large enough to step inside and place it in public space. I was curious to see how our perception changes when we view an image upside down. Would we notice something extraordinary in what we see daily? Unfortunately, the costs of constructing such a device overwhelmed me. Instead, I realized this idea within the confines of my room. Using cardboard and the properties of light, I transformed my room, already positioned on the street, into a camera. I darkened the entire space, leaving a pinhole to create an inverted image. On my table, I saw a fragment of the bridge where train tracks once ran. At that moment, I knew I was inside the camera. The projection was smaller and blurrier than I expected, yet I observed the bridge fragment with a level of attention I’d never given it before. For two years, that view had been the first thing I saw when opening my door. It wasn’t until I saw it upside down that I truly paid attention.

The camera obscura flips the image, and much like binoculars, it allows me to see it with a renewed sense of interest. I read the city upside down. It reminds me of my summer Sunday tradition that I used to have when I was living in a room with access to the garden. I would go out into the garden, lie down on a bench and look at my Dutch house upside down. It brought me such joy that when my friends came over and we had dinner in the garden, we’d do it together. We’d lie on the two benches of the picnic table, simply observing, passing a cigarette under the tabletop.

I continued observing my surroundings. For days, I sat in a square, observing at specific times. I watched my street through the frame of my window. I observed the street corner framing it from a café. I built a device — a tube – for reading the city. I watched the city through a paper frame, a camera, and a film camera lens. I became an expert observer.

The most important function of these framing tools is that they open possibilities without determining what exactly will emerge. Through constraints and limits, unexpected connections arise. I continued this by juxtaposing different combinations. Based on the aforementioned script inspired by The House of Dust by Alison Knowles, I prepared a script that selected entries from various categories and combined them to create prompts for participants in my workshop to build their own paper tools that invite looking at our surrounding differently. Tools we have built included:

A TOOL

FOR people who love surprises

TOO SEE the hidden textures

IN unfamiliar streets

A TOOL

FOR people who speak with their hands

TOO SEE the city as a game

IN the shadowed corners

A TOOL

FOR people who bike everywhere

TOO SEE the stories in gestures

IN shared space

A TOOL

FOR people always in a hurry

TO SEE the passing time

IN an open park at night

A TOOL

FOR for people who adore symmetry

TO SEE the stories

IN a place full of people

Participants using the properties of paper prepared simple tools that, guided steps to take. While still open to interpretation, they enabled specific activities to occur in space. For instance, I drew by lot a prompt:

A TOOL

FOR people who always carry a notebook

TO SEE the choices in how we move

IN open spaces.

I created a sheet with step-by-step folding instructions. Once folded, it could serve as a bookmark in a notebook. When unfolded into a fan shape, it revealed instructions for moving, such as: find corridors between people or notice how space is opening and closing. Each segment displayed a different suggestion for navigating the space.

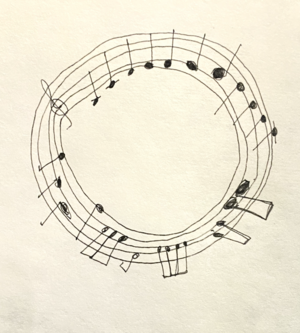

I became intrested in scoring, that share simmilar function. By visually communicating processes happening over time, they allow for the process to constantly evolve. Scores constitute a system of symbols. Elements like time, space, rhythm, and their combinations are presented graphically, visualising a process and influencing it. Scores can be more controlling or more suggestive, but they are always tied to a process and involve certain constraints and limits. For example, the score accompanying Charles Amirkhanian's performance did not dictate exactly how it should be interpreted. It consisted of drawings that could be freely interpreted by musicians, fueling the performance. This approach was not limited to professional musicians; anyone could participate as long as they interpreted the images in their own chosen way. This example demonstrates how playing with chance and control, rather than imposing something, can energize participants' performance. In this case, the score became an opening for chance.

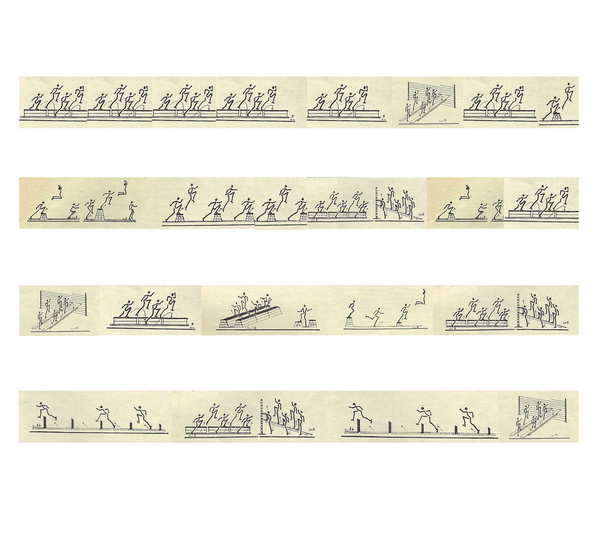

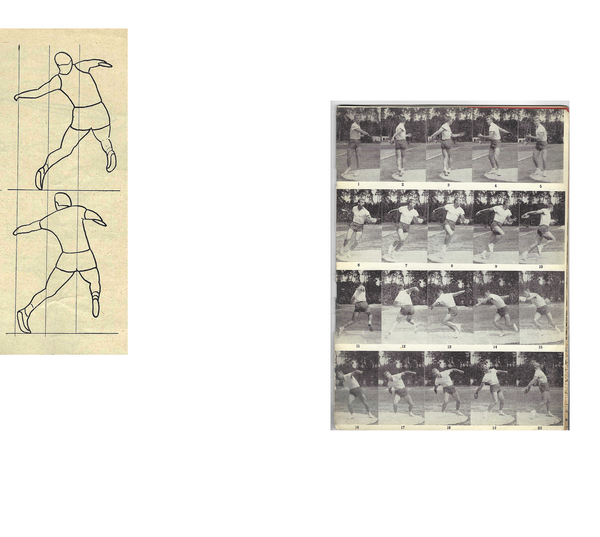

How does this translate to different fields? Going back to the focus of this magazine ( TO SEE the choices in how we move) How can movement be visualized and influenced in a graphical form? There is a difference between graphical representation and the action that results from it. But one informs the other.

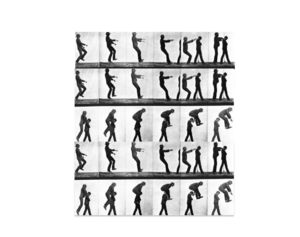

A zoetrope moves individual frames, animating them into smooth motion. But when I look at it as a flat image, it becomes a graphic representation of that movement over time. It reminds me of musical notation. What if I were to record movement using symbols, similar to a musical staff? Instead of a composition, I could record a walk...

The zoetrope, by animating frames arranged in a circle, plays with continuity and repetition. Similarly, I could write notes on a staff that loops into a circle, suggesting that this segment should be played repeatedly, over and over. By playing with this looping, we could create a notation for a walking choreography where you continually turn only to the right, or only take narrow streets. Frames, continuity, repetition.

Once again, I find something surprising and exciting in the imposed constraints.

New fragments

In [title] I reflect on how we perceive our direct surroundings. Perhaps we take these spaces for granted. But maybe we can learn to look at them diffrently to see those spaces as something that we make rather than discover. How can the way we look at our surroundings contribute or inform our transformation of it?

Through the following chapters, I delve into the tools that shape our vision, the methods that encourage spontaneous encounters inspired by the Situationists, and the role of attentiveness. Drawing insights from documentaries and early cinema I aim to uncover ways of paying attention to our surroundings.

Outline update

Chapter 1:

"The process of looking and walking in the city with new and critical eyes already creates entirely new expectations and experiences."

I would like to share what I discovered by navigating the city in this manner, observing the city with attentive eyes. This chapter tells the story of how, through my exploration of the city with a camera, I stumbled upon a lost cinema... and how I created a performance on the building's façade.

Key Themes:

Psychogeography: Understanding urban spaces through spontaneous, unplanned exploration.

Patrick Keiller’s Approach: How walking and film-making can shape our understanding of the city.

Representation vs. Reality: How the cinematic gaze aligns with or diverges from the lived experience of urban space.

Questions to take to the second chapter: How do we cultivate curiosity when exploring familiar places?

Chapter 2

Subjective Experience and familiar places

How do personal and collective memories interact with physical spaces to create emotional geographies?

In this chapter, I delve into how subjective experience shapes our perception and engagement with the world. I discuss how memories shape our relationship with spaces and how we interpret them emotionally.

Key Themes:

Warsaw Walk: A personal journey through the city - the role of memory in shaping the relation with the city.

I begin my walk from the Plac Trzech Krzyży, pass a building with three façades, head towards Mokotowska, and end at the Kino Luna, reflecting on the fate of Luna cinema temporarily closed...

Stewart Home, the English artist and writer who in 1992 revived the London Psychogeographical Association, states:

“For me photography is most alluring when both the person behind the lens and what is being photographed self-consciously manifest their subjectivity. Traveling across ‘Britain’ to discover ‘America’ is only one of the many ways in which such subjectivity might remake the world in both photographic and material form. . . . The psychogeographer . . . knows that the world cannot be recorded, it can only be remade.”

Sally Santon: Her exploration of the unexpected in urban spaces

Chapter 4

Cutting, fragmenting, rearaging - as a way of rewriting / reimagining our spaces

questions: what is a role of imagination in understanding our spaces?

Can psychogeography serve as a tool for resistance against homogenized urban planning?

for the Chapter1

While walking, I discover new meanings and stories that the city hides. The act of walking in the city and looking with curiosity and attention already generates different perspectives.

This summer, I participated in a summer school held in a twin city: Frankfurt Oder and Słubice, and that's how I ended up in this place. I spent two weeks in the twin city. From the moment I arrived, I walked with a small camera, which my parents once used to record our birthdays. Now, this very camera became my tool for discovering the city. The camera, as well as walking, drifting, which took me to random places much like the dérive proposed by the Situationists. Dérive involved wandering through the city without a specific goal, only guided by how the environment influences emotions and behavior. The aim was to break the routine and create new, spontaneous ways of interacting with the city. Participants in these walks explored how specific places and the city's layout affected their behavior and feelings. This allowed people to imagine urban spaces anew, envisioning new functions for these places beyond the utilitarian or commodified ones. In my case, my contemporary drifting was not aimless wandering; it had a purpose. I wanted to reach new places to better understand the twin city. I wanted to find something I could tell in a short film.

“Psychogeographic writing can be thought of as an alternative way of reading the city. Wilfried Hou Je Bek calls it “the city-space cut-up.” Just as William Burroughs and Brion Gysin cut and reorganized newspaper texts to reveal their implicit content, so too psychogeographers decode urban space by moving through it in unexpected ways.” (O'Rourke, 2020)

I want to tell how, by walking through the city and discovering it in fragments through my camera, I found the lost cinema. I don't know Słubice well; I was born and raised in Warsaw. I'm telling this story from the perspective of someone who doesn't live there, but I was intrigued by the history of this place, and this abandoned cinema became dear to me.

And that's how I got to know the place better, walking through it. By walking, I learned things that articles on the internet didn't reveal. The context of these cities was fascinating, as they developed simultaneously and together they are much stronger. Before the war, it was Frankfurt Oder; after the war, the right side of the river became the Polish part. The two cities are now divided by the river and connected by one bridge. Electronic equipment is bought on the German side, while the market it is common to go on the Polish side because it’s much cheaper. Waiters often speak both languages fluently, and on the Polish side, you can pay with both currencies. Every day, I walked along the same path, passing a square, a small park, a parking lot, then crossing the bridge, and immediately after the bridge, turning left to Zukunfpplatz, where I met the rest of the people from the summer school. What amazed me the most was the 16 hairdressers on one street right next to the bridge. Prices are still lower, so Germans cross the bridge and go to the hairdresser on the Polish side. It is still worth it, even though hairdressers have sprung up next to each other like mushrooms after the rain. I walked and observed. I wandered where my intuition led me. Actually, with no plan, not knowing what the new city would reveal to me. My feet turned out to be excellent at reading the city. But the most helpful was the small camera. The collected footage created an increasingly richer image of the city in my eyes. It was wonderful how the film made me braver, more willing to talk to people and ask them about the specifics of the city and life there.

Patrick Keiller, filmmaker, psychogeographer, and writer, believes that film changed how we think about the city. He says that the image becomes a way to investigate. Indeed, walking is also key in his film-making process. In his book review, Michael Pattison writes that Keiller mentioned that at least two of his essays were created when the artist tried to find a place he noticed through the window of a passing train.

I wonder how films construct the image of the city, and how this influences our understanding of urban life. Does it align with or diverge from the lived experience of urban space? Collecting frames from this city and searching for threads to tell in this short film so boldly led me to completely new places. I met many people and learned many stories. Among others, a man from the local radio in Frankfurt Oder, who told me how Polish women created a broadcast about the difficulties related to the abortion ban in Poland. What could not be broadcast on the Polish side, could be highlighted on the German side. This made me realize, how can I tell something about this place, I am only passing through. Especially after the conversation with the very polite man from the market and many others who spoke about the difficulties of life there, I understood that I had no idea what it means to live in Słubice...

Realizing that I am speaking from the position of someone who was only in the city for two weeks, I wanted to express how I feel about this place and what it symbolizes to me. I usually returned to the dorm on the left side of the street, passing by a beautiful old building with a plywood-covered entrance. For so many days, I passed this building, but never really paid attention to it. Once, coming back on the other side of the street, I saw it in its entirety. On the top was the inscription NO PAST, which puzzled me as to what it meant... Then, I noticed the missing letters, and the letters that had fallen off revealed KINO PIAST. (Cinema Piast). I was intrigued by what had happened to these letters. I thought it was a remarkable coincidence that the letters had fallen off, leaving the message NO PAST.

The architect and photographer Lorenzo Servi, whose book I bought in Berlin, organizes walks and workshops with the intention of attentive observation. One of his ways of drawing attention to something and giving it new meaning is to remove the object from its context. This allows one to look at it with new eyes, with a fresh perspective. In this case, it was a bit different. The inscription NO PAST was already taken out of context, but when I noticed the missing letters, it suddenly revealed another meaning, emphasizing the rich history of this place, contrasting with the printed letter inscription. I became interested in this and got in touch with a local journalist to investigate the topic. She, in turn, directed me to an architect who had extensive knowledge about this building. By chance, he responded to my email, and the next day we met in front of the cinema. I learned from him what character this cinema had. Apparently, people loved it, even though from the stories it seemed that the smell was awful. It was probably the dampness caused by the flood that occurred there. However, the cinema was still popular. They supposedly showed great movies. It was run by a man who, during the day, sold flowers in front of the entrance to pay for the projection costs. The changes that occurred in the city ruined it. It's so sad that the residents lost this building. Having only one week left, I felt the desire to bring back the audience to this abandoned building.

In this whole adventure and my drifting through the twin city, the act of walking, observing, and documenting was not meant to present an objective truth about the place, if such a thing even exists, but rather to build a relationship with the place. I know I was there for a very short time, but I didn’t want to just document what I had learned; I had engaged with the fate of the Kino Piast. The cinema’s interior was ruined. Only the façade remained. On both sides of the entrance doors were empty frames where once film posters had hung. It begged to have posters placed in those empty frames again. I organized a performance with a girl from Amsterdam I met there. We prepared a text with memories from people who remembered the cinema and read it in front of the building. The event was accompanied by music and shadow play on the building's façade. We cut shapes out of paper and attached them to sticks. I found old sheets in a flea market hall, and we used them as a background for the shadow projection. Someone had a lamp strong enough for the shadows to be clear. The empty frames on both sides of the entrance doors were filled with new posters inviting passersby to the shadow show. A crowd gathered and participated to create a projection together. It was a beautiful experience to bring an audience back to this cinema, even if only for one evening.

Cities and specific places are not rigid and unchanging. They can be imagined anew through our subjective involvement. And I understood that my subjective perspective is central in how I interpret my environment and interact with it. Lefebvre (1991, p. 73) states that "Space is neither a ‘subject’ nor an ‘object’ but rather a social reality—an outcome of a sequence and set of operations, and thus cannot be reduced to the rank of a simple object."

The tension between what is possible and imagined, and what is realized, holds transformative potential, as long as we navigate its contradictions and hidden possibilities. Just like Keiller's film exploration attempts to reach beyond representation into the realm of action.

"The real work begins, then, in forming a bridge between the conceivable and the actualised. And that bridge might require something beyond the cinematic" (Pattison, n.d.).

Returning to the camera as a tool to investigate the city, I believe it has an impact not only on how we understand these places but also on how we change them. It retains the capacity to surprise, to reveal contradictions, and to invite change.

[<<Here you give a good account of your relationship with encountering the city, and how your methodology developed. This opens the door to address the feedback from the tutors: a series of field studies into particular walks through particular places. {text, maps, visuals} Key to this are observations you make about particular places which affect you, such as "no past", in which the poetry of the city is revealed.

References:

O'Rourke, K., 2020. Psychogeography: A Purposeful Drift Through City Spaces.

Pattison, M., n.d. Keiller’s Cinematic Walks: Finding Beyond Representation.

Lefebvre, H., 1991. The Production of Space.

Warsaw Walk: A personal journey through the city

The role of memory in shaping the relation with the city.

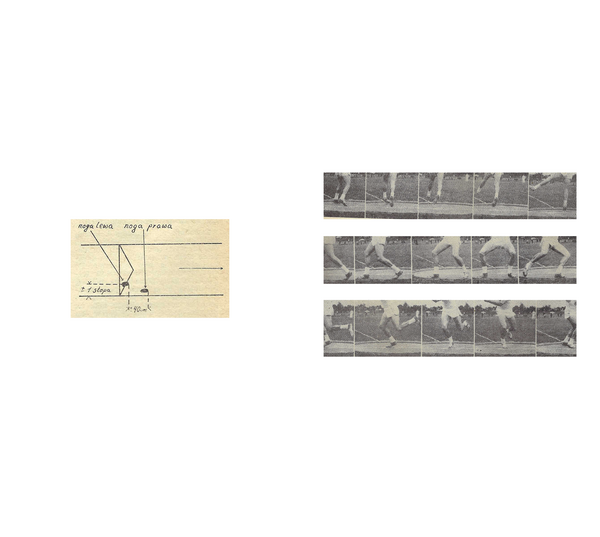

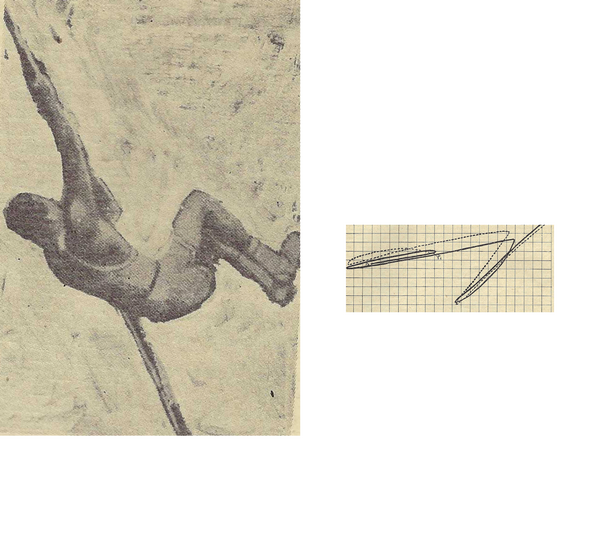

I’ve returned to Warsaw, revisiting familiar places that memories draw me back to. One of them is the Olimpia flea market, but we call it Szukalski from the verb "szukać" which means “search.” And we usually find plenty of treasures. This time, I found old notebooks. Beautiful ones, with lovely patterns on the inside covers, in various formats, some blank, others filled with writing. From a large container, I also dug out magazines about athletics, filled with frame-by-frame photos of athletes. Visually, they reminded me of my experiments with moving images in a zoetrope.

I spent the whole day scanning my finds, cropping the discovered photos, and reading the notes from the notebooks. On the first page of one notebook belonging to a 4th-grade student, there was a note:

“Please excuse Rafał from the last three lessons as we have a doctor’s appointment for an eye check-up.” I wonder if Rafał really went to the eye doctor… or perhaps he was running around Pole Mokotowskie, like I used to do in high school when we went there instead of math classes. Browsing through these notebooks brings back so many memories. They’ve become like guides through space as they filled me with a desire to revisit certain places.

Inspired, the next day I set off for a walk with no particular plan of where to go, but I’m determined to visit Pole Mokotowskie, imagining Rafał from the notebook running across the grass on April 4, 1986.

I started my walk at Plac Trzech Krzyży. Passing a building with three facades, I head towards Mokotowska Street. From afar, I see my favorite bookstore, Bęc Zmiana, still closed. In the window display, I spot a book that catches my interest—Szwendownik. It must be about wandering through the city. Perfect, as that’s exactly what I’m doing now. I’m curious and want to flip through it. The bookstore opens in 30 minutes, so I decide to wait. I missed this place. Standing outside, I genuinely feel happy at the sight of it. I photograph the window display. Next to the entrance, I see a photograph on the wall, showing a woman’s legs on a sidewalk. I’m certain I’ve seen it somewhere before, but I can’t recall where. It reminds me of fragments I cut out from the materials I found at Szukalskifor my collages about urban choreography.

I immediately ask my Warsaw friends if the photo hanging near Bęc Zmiana means anything to them or if they know the author. I feel like a detective, but so far, no clues. I walk a bit further to grab a coffee in the meantime. I return to Bęc Zmiana and ask inside about the photo’s author, but I only learned that some girls were hanging their photos around Warsaw. A sort of urban exhibition. This reminded me of a small display case near Plac Zbawiciela, where someone used to arrange mini-exhibitions of various objects. I want to find it and check if it’s still there. This thought guides me further through the city. I continue along Mokotowska Street, some new shops have opened there.

I’m close to Plac Zbawiciela, almost at the corner, with a little square to my left where we used to play flanki. At the roundabout, I turn right—that’s where the little display case used to be. It’s no longer there. The door has been ripped off, and inside there’s a blanket and an empty coffee cup. I’m curious who left it there. What did they want to communicate to us? The glass has been covered with posters. What could its alternative function be? Did the former mini-exhibition case change its purpose and become a hiding place?

I arrive at Pole Mokotowskie Park. I see the hill where my friends and I used to come in the spring instead of math class. We would lie on the grass and even solve those problems together, but it was blissful. I photograph this spot and paste it into a found academic notebook, over a background of complex calculations.

I look around. How many memories are waiting for me here? I glance at the “Grzybek” (the mushroom-shaped pavilion). How shabby it looks now. But it was there that my first boyfriend and I told each other we loved each other.

I continue my walk along my beloved Oleandrów Street. My English teacher used to live there before she moved to England. I end up practically in front of Kino Luna. I find its entrance blocked, with several posters informing that the cinema isn’t disappearing. Was it supposed to?

Here my walk ends. It was memories that guided me through these places….

Found notebooks

Intro (21.01)

This text serves as an opening to uncovering ways of seeing and relating to our cities. This exploration started with a question How do tools shape how we perceive our immediate environment? How a magazine a physical object can become one of these tools? I want to design a magazine that doesn't only depict our surroundings but becomes a tool to actively engage readers in experiencing and reinterpreting them. A magazine meant to be read outside, creating new forms of engagement with the city, by exploring the potential of paper. Through folding and cutting and the possibilities of shaping it and printing on it, paper has the capacity for remarkable things and I’m curios to find out in what ways it can help us observe our surroundings.

With this paper, I dedicate time to exploring my neighborhood, moving through various places with curious eyes. It weaves together fragments from my notebook, turning writing into a dialogue with walking, collecting, and rearranging fragments. I seek to embrace unpredictability and surprises in familiar surroundings, fostering exciting connections and interactions in shared spaces.

(The way my explorations have now developed is by exploring the performative value that a book offers. What kind of audience it gathers around itself or engages in the process of its creation. And how it creates space—whether emotional, physical, or social.)

Chapter 1 ( 21.01)

Reading the city isn’t just about observing it from a distance. The more I observed, the more I realized how complex and multi-layered cities are, interwoven with countless stories. Reading a city means being genuinely curious about its people and surroundings. It means engaging with the world and continually evolving your perception of it.

It involves being open to unexpected opportunities that arise IN unfamiliar streets, IN shadowed corners, IN familiar spaces, IN chaotic streets, IN the spaces in-between, IN spaces of certainty, IN neighborhood park, IN museum courtyards, IN crowded markets, IN city squares, IN quiet side streets, IN leisure spaces, IN shared spaces, IN spaces full of people, IN parking spaces, and open spaces. There are PEOPLE always in a hurry, PEOPLE who sing to themselves, PEOPLE who take detours, PEOPLE who carry notebooks, PEOPLE lost in their thoughts, PEOPLE who bike everywhere, PEOPLE who dream vividly, PEOPLE who miss their hometowns, PEOPLE who never stop questioning, PEOPLE walking alone, PEOPLE who adore symmetry, PEOPLE who enjoy getting lost, PEOPLE who love surprises, PEOPLE who stay up late, PEOPLE who speak with their hands, PEOPLE who feel out of place, PEOPLE walking slowly, and PEOPLE speaking many languages, shaping the spaces we inhabit. Perhaps we take these spaces for granted, moving through them daily without much thought. But maybe we can learn to see them differently: TO SEE the long way home, TO SEE the stories in gestures, TO SEE the endless possibilities, TO SEE the rhythm of the city, TO SEE the connections, TO SEE the hidden textures, TO SEE the passing time, TO SEE the absurdity, TO SEE the hidden shortcuts, TO SEE the unexpected, TO SEE the structures, TO SEE the stories, TO SEE the choices in how we move, TO SEE the city’s edges, TO SEE the city as a game, TO SEE hidden playgrounds, TO SEE new paths, TO SEE the extraordinary in the ordinary, TO SEE the absence, TO SEE what’s written in the street. Then, nothing will stop us from reimagining these spaces, and possible ways of navigating them. I believe the first step is to pay attention.

My fascination with framing started this summer, with a pair of binoculars I bought at a market for three euros. Totally absorbed, I spent hours on Yana's balcony, observing the rooftops of Sofia—textures, antennas, and edges. Gradually, fragments of the city revealed themselves to me. Serendipity played a role in these observations, and I couldn’t have been happier, as I noticed things that usually go unnoticed. The binoculars became my tool for reading the city and found a permanent place in my routine. With a newfound interest, I scanned buildings, gliding along their lines. They made me notice houses that look like they are hugging the one in the middle. Passersbys entered and exited my frame, suddenly, the city became full of surprises. I became obsessed. Through them, I observed Sofia, Warsaw, Frankfurt-Oder and Słubice, Rotterdam, and Groningen. It fascinated me how even the simplest tool, with its inherent limitations, could be an opening for so many surprises. What I mean is all the things I have seen before but ignored. I find it intresting how narrowing the field of vision, allows for looking at the city piece by piece and brings a specific fragment to the front.

Inspired by that, I decided to build a camera obscura large enough to step inside and place it in public space. I was curious to see how our perception changes when we view an image upside down. Would we notice something extraordinary in what we see daily? Unfortunately, the costs of constructing such a device overwhelmed me. Instead, I realized this idea within the confines of my room. Using cardboard and the properties of light, I transformed my room, already positioned on the street, into a camera. I darkened the entire space, leaving a pinhole to create an inverted image. On my table, I saw a fragment of the bridge where train tracks once ran. At that moment, I knew I was inside the camera. The projection was smaller and blurrier than I expected, yet I observed the bridge fragment with a level of attention I’d never given it before. For two years, that view had been the first thing I saw when opening my door. It wasn’t until I saw it upside down that I truly paid attention.

The camera obscura flips the image, and much like binoculars, it allows me to see it with a renewed sense of interest. I read the city upside down. It reminds me of my summer Sunday tradition that I used to have when I was living in a room with access to the garden. I would go out into the garden, lie down on a bench and look at my Dutch house upside down. It brought me such joy that when my friends came over and we had dinner in the garden, we’d do it together. We’d lie on the two benches of the picnic table, simply observing, passing a cigarette under the tabletop.

I continued observing my surroundings. For days, I sat in a square, observing at specific times. I watched my street through the frame of my window. I observed the street corner framing it from a café. I built a device — a tube – for reading the city. I watched the city through a paper frame, a camera, and a film camera lens. I became an expert observer.

The most important function of these framing tools is that they open possibilities without determining what exactly will emerge. Sister Corita Kent used the simplest tool for this purpose, which she called a "finder." A piece of paper with a cut-out opening was used to learn how to look at what surrounds us, piece by piece. Through constraints and limits, unexpected connections arise. I continued this exploration by juxtaposing different combinations. Based on the script inspired by The House of Dust by Alison Knowles, I prepared a script that selected entries from various categories and combined them to create prompts for participants in my workshop to build their own paper tools that invite looking at our surrounding differently. Tools we have built included:

A TOOL FOR people who love surprises TOO SEE the hidden textures IN unfamiliar streets

A TOOL FOR people who speak with their hands TOO SEE the city as a game IN the shadowed corners

A TOOL FOR people who bike everywhere TOO SEE the stories in gestures IN shared space

A TOOL FOR people always in a hurry TO SEE the passing time IN an open park at night

A TOOL FOR for people who adore symmetry TO SEE the stories IN a place full of people

Participants using the properties of paper prepared simple tools that served as prompts. While still open to interpretation, they enabled specific activities to occur in space. For instance, I drew by lot a prompt:

A TOOL FOR people who always carry a notebook TO SEE the choices in how we move IN open spaces.

I created a sheet with step-by-step folding instructions. Once folded, it could serve as a bookmark in a notebook. When unfolded into a fan shape, it revealed instructions for moving, such as: find corridors between people or notice how space is opening and closing. Each segment displayed a different suggestion for navigating the space. What do you gain from using such tools? Isn’t curiosity and simply being in a space, observing what surrounds us, enough? Devoting time and attention seems sufficient, yet so much escapes us and remains unnoticed.These seemingly funny paper tools containing suggestions on how to navigate space turned out to be an effective invitation to play and a kind of three-dimensional score for observing anew. I come to the conclusion that the best way to look at the surroundings I know by heart with curious eyes is to observe weirder and try different tactics. Perception is not fixed. It can change and evolve, and in fact, it takes action.

I move from mere observation to the more active forms of engagement to continue exploration of my neigbourhood. ( this part will belong to chapter 1 but its still in the process)

The act of walking in the city and looking with curiosity and attention already generates different perspectives. Dérive involved wandering through the city without a specific goal, only guided by how the environment influences emotions and behavior. The aim was to break the routine and create new, spontaneous ways of interacting with the city. Participants in these walks explored how specific places and the city's layout affected their behavior and feelings. This allowed people to imagine urban spaces anew, envisioning new functions for these places beyond the utilitarian or commodified ones. I think it's our human skill that we know how to get lost. It’s more about seeing a familiar space from a new perspective, looking at it differently. Just like urban planners use those glasses on sticks, whose height corresponds to a child's height, allowing them to experience the city from a child's perspective. Similarly, this is about initiating a situation that will reverse my so familiar image of the nearest surroundings. How do tools act as “invitations” rather than prescriptions for exploration?

I return to the notes from a conference about neighborhoods. During a presentation I attended at a conference Neighbourhoods as learning environments, a speaker shared the following guiding principles, which I adapted as scores for my exploration. The note is incomplete because I wrote it while listening, but this presentation particularly stuck in my memory.

"Listen to a place

Look what is already out there

What are the limitations of the practice?

Who is active?

How can you support what is already happening

Curate a dialogue

Look at the space as if you are looking at it for the first time

Have patience

Have you changed after the work?

Try different tactics

Find like minded people

Whose perspectives are misssing?

Practice power sharing

What participants need?

Turn it into a graphic novel

How participants perceive gentrification?

Invite your neigbours for a picnic

Draw portraits of your neighbours and ask them for their stories

Be present at the local markets

Give small things a big stage

Don't be afraid of words

Look at the means of production

Be aware

Communal love

Make the work visible

Do u have support?

Be aware of your power

Be soft

Step back, give voice

Share autorship"

While I could not trace the original source, these principles influenced the development of my methodologies. I treated that note as instrctions, as scores to find diffreent tactics to explore my neighbourhood. In order to see the familiar space differently, I propose methods for more active participation.

Scores constitute a system of symbols, visualising a process and influencing it. Scores can be more controlling or more suggestive. For example, the score accompanying Charles Amirkhanian's performance did not dictate exactly how it should be interpreted. It consisted of drawings that could be freely interpreted by musicians, fueling the performance. This approach was not limited to professional musicians; anyone could participate as long as they interpreted the images in their own chosen way. This example demonstrates how playing with chance and control, rather than imposing something, can energize participants' performance. In this case, the score became an opening for chance.

(I will contine to desribe my experiments with Scores in the environment

- Invitation to embark on a walk - shared in a form of a poster

- Passing on my zine in a neighbourhood street library

- Set of scores)

Chapter 2 ( 21.01) Looking outwards

What drives my magazine, the values I want it to embody, are curiosity, friction, connection. I want to design with an eye toward the situations that the book could inspire—how it might contribute to creating moments… in cities where experiences are becoming increasingly seamless. We have services that deliver groceries to our doors, dating apps, and smart solutions that provide us with comfort, but they also create a frictionless environment. René Boer’s concept of the “Smooth City” ties into this idea. He argues that while everyone deserves a safe and clean environment, such pervasive smoothness gradually eliminates opportunities for serendipity, potential, encounters, and all those unplanned, unexpected events.This makes me ask, what kind of cities do we really want? Do we prefer a predictable, frictionless environment, or do we embrace randomness and chance? Personally, I long for a city where, I enjoy conversations with strangers, where not everything is reduced to the same polished appearance—a city created by people and therefore full of potential. What a nice challenge for a magazine: to foster friction… to seek ways to open up to different experiences, exciting connections, and interactions with others in shared spaces. To be a tool to help me see my neighborhood in a completely different way, to step outside the frames of my perception, to look not inward but to truly look beyond the limits of my assumptions. Look outward. It opened up avenues for connecting with others.

"Making a book is a delightful process. It compels us to focus, demands editing and making choices. Ultimately, it's an instrument for concentration and contemplation. A book marks a beginning and an end. But it’s also a social tool, bringing people and ideas together as a mobilizing subject; building new communities and empowering other futures." (The future of the book is beyond a book - Annelys de Vet, p.22)

Subjective atlases offer an example of how books can transcend the boundaries of mere documentation. By engaging residents to represent a city or region, they strengthen participatory processes. With this approach a book becomes not just a repository for knowledge, but a tool for connection, and action. The publication became a pretext and an invitation to gather together. As Annelys de Vet describes it, inviting people to engage in collective mapping, based on their own experiences and situated knowledge: “It provided a shared goal that allowed us to decode the bigger systems of representation that so often define us.”

During a one-day artistic residency, which focused on the theme of the neighborhood, I wanted to explore this very idea. What audience does a book gather around itself, and how does it create the opportunity to see things from someone else’s perspective? I approach this with the intention of looking outward—to do this, I planned to curate a dialogue. Talking to people about whether they have any personal habits when moving through their neighborhood. How do these habits connect them to the space? Are there places that encourage interactions with their neighbors? I collected fragments of texts from people about the smallest things that are already there, things they appreciate. I want to give small things a big stage. I assembled these fragments into a whole, creating a long list of small things. At the end, when we all gathered together, I read these fragments aloud, expanding the list as we listened together. The act of READING AND LISTENING TOGETHER became a performative aspect of the mini publication, which created a space where different voices could coexist. Under the pretext of sharing observations from personal experiences, I began to decode my own image of the city.

First draft 14.02

Intro

This text serves as an opening to uncovering ways of seeing and relating to our cities. This exploration started with a question How do tools shape how we perceive our immediate environment? How a magazine a physical object can become one of these tools? I want to design a magazine that doesn't only depict our surroundings but engage readers in experiencing and reinterpreting them. A magazine meant to be read outside, creating new forms of engagement with the city, by treating it as a portable tool.

With this paper, I dedicate time to exploring my neighbourhood, moving through various places with curious eyes. It weaves together my observations with other texts, turning writing into a dialogue with walking and collecting.

Chapter 1: A Tool For People To See

A TOOL

FOR PEOPLE

TO SEE

Reading the city isn’t just about observing it from a distance. The more I observed, the more I realized how complex and multi-layered cities are, interwoven with countless stories. Reading a city means being genuinely curious about its people and surroundings. It means engaging with the world and continually evolving your perception of it. To see the city as something that can be read suggests that it can also be rewritten. It’s like looking at it as something that we not only discover but also make. The way I innitially referred to the concept of reading the city was because I wanted to emphasize that observing the city is not a cold act from a distance, that by moving around in different ways, having interactions, interventions, touching textures, I also discover them. Following this thought, city can be read with both eyes and feet. In fact it has little to do with reading and a lot to do with experiencing. In my case, it starts from street observation, which experiments with different tactics to shift perspectives—scores, playful paper objects, drifting.

Reading the city involves being open to unexpected opportunities that arise IN unfamiliar streets / IN shadowed corners / IN familiar spaces / IN chaotic streets /IN the spaces in-between / IN spaces of certainty / IN neighborhood park / IN museum courtyards / IN crowded markets / IN city squares / IN quiet side streets / IN leisure spaces / IN shared spaces / IN spaces full of people / IN parking spaces / IN open spaces.

It involves noticing who is around you. There are PEOPLE always in a hurry / PEOPLE who sing to themselves / PEOPLE who take detours / PEOPLE who carry notebooks / PEOPLE lost in their thoughts / PEOPLE who bike everywhere / PEOPLE who dream vividly / PEOPLE who miss their hometowns / PEOPLE who never stop questioning / PEOPLE walking alone / PEOPLE who adore symmetry / PEOPLE who enjoy getting lost / PEOPLE who love surprises / PEOPLE who stay up late / PEOPLE who speak with their hands / PEOPLE who feel out of place / PEOPLE walking slowly / PEOPLE speaking many languages, shaping the spaces we inhabit.

Perhaps we take these spaces for granted, moving through them daily without much thought. But maybe we can learn to see them differently: TO SEE the long way home / TO SEE the stories in gestures / TO SEE the endless possibilities / TO SEE the rhythm of the city / TO SEE the connections / TO SEE the hidden textures / TO SEE the passing time / TO SEE the absurdity / TO SEE the hidden shortcuts / TO SEE the unexpected / TO SEE the structures / TO SEE the stories / TO SEE the choices in how we move / TO SEE the city’s edges / TO SEE the city as a game / TO SEE hidden playgrounds / TO SEE new paths / TO SEE the extraordinary in the ordinary / TO SEE the absence / TO SEE what’s written in the street. Then, nothing will stop us from reimagining these spaces. I believe the first step is to pay attention.

Georges Perec's text Species of Spaces and Other Pieces (1974) is a reflection on how we experience space, from the smallest—like a page or a bed to streets, cities, and the world. In his opinion, the problem is not inventing space anew, but how we question that space, how we read it. His text collects these observations, which he often lists in the form of inventories. The text encourages the reader to pay attention to ordinary places in a new way. Perec sees cities as spaces full of surprises. He explores how we engage with our everyday surroundings. We do not think enough about these familiar places, and even the most well-known spaces hide deeper meanings.

Perec lists his observations in the form of an inventory. In his view, everyday life around us is not something obvious. He wrote down what he saw, questioning what demanded his attention and what did not, giving equal importance to things that could easily go unnoticed.

Similarly, I try to list what happens before my eyes, the living fabric of the city—not just what loudly calls for my attention. I searched for lists from my notebooks. These are mostly records from my immediate surroundings but also from other places in Rotterdam. I try to look at a place that seems familiar to me, as I know it like my own pocket, but from a new perspective. Recording space as text...Many of the lists from my direct surroundings reveal people that I notice, road signs that navigate us through space, many cafés, and actually not so many places where you can sit without buying something first. Reading my lists of what I see in space, it becomes clearer what is missing in it. Or who is not included in that list.

I am reminded of the text Smooth City by René Boer, which has greatly influenced my thinking about the city. Unlike Perec, Boer is much more concrete in his critique. He brings up specific examples and observations of how contemporary cities prioritize order and efficiency, calling this state smoothness. No surprise, after all, it is characterized by being frictionless. The author mentions that during a walk around the neighborhood in Amsterdam, everything was:

-Renovated

-Restored

-Repaired

-Repolished

-Renewed

- No forgotten corners

- No undefined elements

- Nothing left to gradually transform at its own pace

- No traces or marks of people presence

- No dirt

- No friction

- No temporary transformations

- No smells

- No contrast

- No stickers with political messages

- No unexpected behaviour

- No absurd

- No trouble

- No alternative narratives

Everything runs smoothly, clean and is designed for convenience. In a smooth city, we don’t even have to wait for anything, digital technologies make services instant, everything happens immediately and basically without leaving home. There is not even a chance to be bored for a moment, and yet boredom can be so creative. I'm quite impatient myself, but now thinking about the fact that avoiding conversation I can order food delivery through existing apps, or order a taxi in a few seconds, right under my nose, use dating apps without leaving home, I realize these services are seamless and fast, but at the same time, they tighten control over public space. This convenience happens at the cost of spontaneity and diversity. The humorous collages accompanying the book joke about this perfect environment, mixing surroundings that seem almost staged. Shiny clean spaces bearing witness to comfort, gleaming elements, happy people, steel and glass, convenience, and at every step, advertisements whispering promises of luxury.

Is this “rendered perfection” worth it?

I watched the movie Playtime in which Tati criticizes and makes fun of how modern cities try at all costs to be efficient but end up feeling alienating. The main character gets lost in a city of steel and glass, a city filled with technology. The film does not have a single plot but rather presents many different characters as they move through a futuristic city. Their behaviors are so well orchestrated that it reminds me of the animation Tango by Zbiegniew Rybczyński (1981), in which the action takes place in one room, into which characters enter and leave, each busy with their own activity, repeating their actions, and not getting in each other's way. Similarly, in the Playtime movie, the characters were isolated and I felt like I was spying on them, even though I would have preferred to be in dialogue with them. This automation, confusing technology, identical buildings, and this rawness felt terribly cold, while I would have preferred to know what these characters were thinking. The film shows a controlled, rigid city where technology is supposed to make life easier, but often but often confuses the characters. To be honest, it was hard for me to concentrate, it seemed disconnected. Only at the end the characters break away from this order, reminding us that we can't work non-stop and be productive all the time.

Productivity and efficiency at all costs come

at the expense of relationships,

at the expense of boredom, which can be so creative,

at the expense of getting lost in the city and discovering random places,

at the expense of mistakes that teach,

at the expense of carefree, unproductive fun.

Perec in a poetic way spoke about the attempt to describe a space without a use, a non-productive space, a space-nothing, admitting that he was unable to describe this nothingness. As he himself states: “…as if we could only speak of what is full, useful, and functional." (Perec, Species of Spaces and Other Pieces, 1974)

In a city so focused on success, achieving, gaining and improving everything to function faster, better and more, difference and unpredictability become flattened. This way, the city serves the needs of a selected group. Boer stands for more open places. Places that allow for resistance, creativity, and real human connections. The kind of city I desire is in agreement with Boer, more open spaces for genuine connection, which is more important than eficiency at all cost.

Wanting to engage in observing my neighborhood in a non-functional way, I begin by looking piece by piece, not only at what screams for my attention, but what happens directly in front of my eyes. Even the simplest tools, like a paper tube or an ordinary sheet of paper with a cut-out frame, turned out to be very helpful in this process. By bringing a specific fragment to the foreground, as if cutting it out of its context, it allowed me to see it anew. For some reason, it is easier to focus on a fragment when it is removed from its context I can then in a way uncover its hidden meanings.

My fascination with framing started this summer, with a pair of binoculars I bought at a market for three euros. Totally absorbed, I spent hours observing the rooftops of Sofia—textures, antennas, and edges. Gradually, fragments of the city revealed themselves to me. Serendipity played a role in these observations, and I couldn’t have been happier, as I noticed things that usually go unnoticed. The binoculars became my tool for reading the city and found a permanent place in my routine. With a newfound interest, I scanned buildings, gliding along their lines. They made me notice houses that look like they are hugging the one in the middle. Passersbys entered and exited my frame, suddenly, the city became full of surprises. I became obsessed. Through them, I observed Sofia, Warsaw, Frankfurt-Oder and Słubice, Rotterdam, and Groningen. It fascinated me how even the simplest tool, with its inherent limitations, could be an opening for so many surprises. What I mean is all the things I have seen before but ignored. I find it intresting how narrowing the field of vision, allows for looking at the city piece by piece and brings a specific fragment to the front.

Inspired by that, I decided to build a camera obscura large enough to step inside and place it in public space. I was curious to see how our perception changes when we view an image upside down. Would we notice something extraordinary in what we see daily? Unfortunately, the costs of constructing such a device overwhelmed me. Instead, I realized this idea within the confines of my room. Using cardboard and the properties of light, I transformed my room, already positioned on the street, into a camera. I darkened the entire space, leaving a pinhole to create an inverted image. On my table, I saw a fragment of the bridge where train tracks once ran. At that moment, I knew I was inside the camera. The projection was smaller and blurrier than I expected, yet I observed the bridge fragment with a level of attention I’d never given it before. For two years, that view had been the first thing I saw when opening my door. It wasn’t until I saw it upside down that I truly paid attention.

The camera obscura flips the image, and much like binoculars, it allows me to see it with a renewed sense of interest. I read the city upside down. It reminds me of my summer Sunday tradition that I used to have when I was living in a room with access to the garden. I would go out into the garden, lie down on a bench and look at my Dutch house upside down. It brought me such joy that when my friends came over and we had dinner in the garden, we’d do it together. We’d lie on the two benches of the picnic table, simply observing, passing a cigarette under the tabletop.

I continued observing my surroundings. For days, I sat in a square, observing at specific times. I watched my street through the frame of my window. I built a device — a tube – for reading the city. I watched the city through a paper frame, a camera, and a film camera lens. I became an expert observer.

The most important function of these framing tools is that they open possibilities without determining what exactly will emerge. Sister Corita Kent, who was a nun and educator, used the simplest tool for this purpose, which she called a "finder." A piece of paper with a cut-out opening was used to learn how to look at what surrounds us, piece by piece. Through constraints and limits, unexpected connections arise. I continued this exploration by juxtaposing different combinations. I was deeply inspired by the work The House of Dust by Allison Knowles. The script randomly combined words into poetic combinations, which the author treated as inspiration. It starts as a computer-generated poem, but it doesn’t remain just that. The author interpreted these combinations and actually built these houses. By playing with the text and the performative aspect, the poem became something like a score, open to interpretation. I prepared a script that selected entries from various categories and combined them to create prompts for participants in my workshop to build their own paper tools that invite looking at our surrounding differently.

Tools we have built included:

A TOOL FOR people who love surprises TOO SEE the hidden textures IN unfamiliar streets

A TOOL FOR people who speak with their hands TOO SEE the city as a game IN the shadowed corners

A TOOL FOR people who bike everywhere TOO SEE the stories in gestures IN shared space

A TOOL FOR people always in a hurry TO SEE the passing time IN an open park at night

A TOOL FOR for people who adore symmetry TO SEE the stories IN a place full of people

Participants using the properties of paper prepared simple objects with scores or instructions that served as prompts. While still open to interpretation, they enabled specific activities to occur in space. What do you gain from using such tools? Isn’t curiosity and simply being in a space, observing what surrounds us, enough? Devoting time and attention seems sufficient, yet so much escapes us and remains unnoticed.These seemingly funny paper tools containing suggestions on how to navigate space turned out to be an effective invitation to play and a kind of three-dimensional score for observing anew. I come to the conclusion that the best way to look at the surroundings I know by heart is to observe weirder and try different tactics. Perception is not fixed. It can change and evolve, and in fact, it takes action.

These methods became helpful not because of their mere functionality, but because they turned out to be playful. Careful observation of everyday details revealed connections. Everything can be coded. I used computer to generate a random combination, this technology initiated the experience of space differently than in everyday life. With this method I ended up reading the city not only with my eyes but by engaing more actively with space.

Chapter 2

FOR PEOPLE who miss their hometown

TO SEE absurdity

IN spaces in between

(Images only )

Chapter 3

FOR PEOPLE who always carry a notebook

TOO SEE the choices in how we move

IN open space

The experiment in visual connections reminds me of Jacquline de Jong's magazine, which was full of unexpected connections.

Jacqueline de Jong started magazine The Situationist Times in 1962 as a response to conflicts within the Situationist International (SI). The Situationists focused around the critique of the Society of Spectacle, but Debord's behaviour was also quite “spectacular”: considering the way he eliminated so many creative people from the movement (De Jong was one of them). De Jong wanted to do something with a more autonomous approach, less focused on politics and more on creativity. Unlike SI, controlled by Debord and being very political and focused on theory, The Situationist Times was more open, experimental, playful, mixing topology, linguistics, found images and politics freely. De Jong was interested in making the magazine more about creative connections than strict ideology. The magazine didn’t follow a strict format, but instead, it brought together unexpected visual connections. Each issue explored a different theme, like knots or labyrinths. The Situationist Times was an experiment in making connections, and seeing the world in a different way. The magazine was a way to keep multi-disciplinary spirit of SI movement, without strict ideological constraints.

Similarly, while working on my magazine, I treated these juxtaposed words as an experiment in noticing connections.

FOR people who always carry a notebook

TOO SEE the choices in how we move

IN open space

I observed how city planning and street signs dictate movement and navigate us through space. I question whether architecture could loosen its constraints and allow for an urban choreography shaped by play rather than control.