User:Zuhui//Personal Reader/What the Luddites Really Fought Against

What the Luddites Really Fought Against by Richard Conniff, 2011

it's a great gateway article to explore what the Luddites are and who they were.

also look for,

wikipedia, Luddite

Neo-Luddism

Against Technology: From the Luddites to Neo Luddism, Steven E. Jones

Writings of the Luddites, Kevin Binfield

Breaking Things at Work: The Luddites Are Right About Why You Hate Your Job, Gavin Mueller

blood in the machine: the origins of the rebellion against big tech, Brian Merchant

Despite their modern reputation, the original Luddites were neither opposed to technology nor inept at using it. Many were highly skilled machine operators in the textile industry. Nor was the technology they attacked particularly new. Moreover, the idea of smashing machines as a form of industrial protest did not begin or end with them. In truth, the secret of their enduring reputation depends less on what they did than on the name under which they did it. You could say they were good at branding.

the Luddites weren't the only ones who destroyed machines, they were exceptionally good at branding

- they weren't against technology

- according to Wikipedia, nowadays, the term "Luddite" often is used to describe someone who is opposed or resistant to new technologies. but the original Luddites of the early 19th century weren’t against new technology itself. Their real issue was how it was being misused.

- They were skilled machine operators in the textile industry, and their protests weren’t just about destroying machines for the sake of it. They were fighting against manufacturers who were using machines to impose unfair working conditions.

As the Industrial Revolution began, workers naturally worried about being displaced by increasingly efficient machines. But the Luddites themselves “were totally fine with machines,” says Kevin Binfield, editor of the 2004 collection Writings of the Luddites. They confined their attacks to manufacturers who used machines in what they called “a fraudulent and deceitful manner” to get around standard labor practices. “They just wanted machines that made high-quality goods,” says Binfield, “and they wanted these machines to be run by workers who had gone through an apprenticeship and got paid decent wages. Those were their only concerns.”

- the machine they destroyed werenb't even new

- the stocking frames they smashed had been around for nearly 200 years by then. their actions weren’t just a automatic reaction to new technologies, but a response to social and economic frustrations.

- they weren't the only ones destroying machines

- even before and after the Luddites, destroying machines was a common form of resistance to industrial change. Similar incidents happened in late 18th-century Britain and France, where workers reacted to technological shifts in more or less the same way.

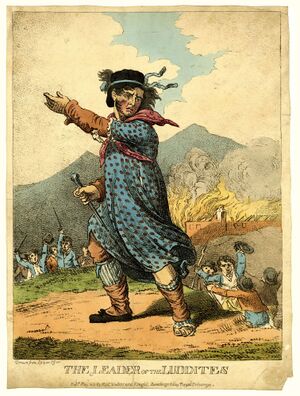

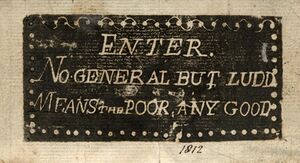

- the good branding

- the Luddites adopted the fictional character ‘Ned Ludd’ as their symbolic leader. He was portrayed as a legendary figure, and his name was used to sign threatening letters sent to factories or to lead protests. which played a crucial role in the movement's unity and identity.

- the execution of machine-breaking was pretty dramatic too. they did it in a rather theatrical way by using a massive hammer called the “Great Enoch,” linking it to local legends. with the catchy slogan: "Enoch made them, and Enoch shall break them". which is pretty genious. giving a tool of destruction its own story turns what could've been seen as simple vandalism into something way bigger and cultural. super cool.

- they framed their protest as social satire too, by using sybolic actions such as marching in women's clothing and distributing witty, satirical pamphlets.

This knack for expressing anger with style and even swagger gave their cause a personality.

Luddism stuck in the collective memory because it seemed larger than life.

And their timing was right, coming at the start of what the Scottish essayist Thomas Carlyle later called “a mechanical age.”

"The indignation of nineteenth-century producers, has yielded to the irritation of late-twentieth-century consumers."

wrote the historian Edward Tenner. this is a very interesting insight, it points out that our attitude towards technology has changed significantly.

for the 19th century Luddites, the threat of technology and its misuse was something worth fighting against, while putting their life on the line. because it really was a matter of survival and keeping livelihood, they believed that technology was disrupting the existing social and economic order.

and now, late 20th century onwards, consumers accepted technology as an inevitable element that could not be rejected. and the response is limited to expressing dissatisfaction with the inconveniences and side effects it brings.

Question

The original Luddites lived in an era of “reassuringly clear-cut targets—machines one could still destroy with a sledgehammer,” Loyola’s Jones writes in his 2006 book Against Technology, making them easy to romanticize.

By contrast, our technology is as nebulous as “the cloud,” that Web-based limbo where our digital thoughts increasingly go to spend eternity. It’s as liquid as the chemical contaminants our infants suck down with their mothers’ milk and as ubiquitous as the genetically modified crops in our gas tanks and on our dinner plates.

Technology is everywhere, knows all our thoughts and, in the words of the technology utopian Kevin Kelly, is even “a divine phenomenon that is a reflection of God.” Who are we to resist?

my god

The original Luddites would answer that we are human. Getting past the myth and seeing their protest more clearly is a reminder that it’s possible to live well with technology—but only if we continually question the ways it shapes our lives.

It’s about small things, like now and then cutting the cord, shutting down the smartphone and going out for a walk. But it needs to be about big things, too, like standing up against technologies that put money or convenience above other human values.

If we don’t want to become, as Carlyle warned, “mechanical in head and in heart,” it may help, every now and then, to ask which of our modern machines General and Eliza Ludd would choose to break. And which they would use to break them.