User:Mania/Thesis - working document

Steve's notes

[What a GREAT START! there is a really rich mix here: your diaristic style works very well, the visual material you draw on is germane, and the references are there, without being didactic. My suggested edits are in bold and my comments are green. On Thursday let's discuss how you can bring in material from proposal, public moments, fake assessment, into the thesis (to describe project &c).]

Intro - draft

In [title] I reflect on how we perceive our direct surroundings. Perhaps we take these spaces for granted. But maybe we can learn to look at them diffrently to see those spaces as something that we make rather than discover. Through the following chapters, I delve into the tools that shape our vision, the methods that encourage spontaneous encounters inspired by the Situationists, and the role of attentiveness. Drawing insights from documentaries and early cinema I aim to uncover ways of paying attention to our surroundings.

Chapter 1 - draft

Reading the city isn’t just about observing it from a distance. The more I observed, the more I realized how complex and multi-layered cities are, interwoven with countless stories. Reading a city means being genuinely curious about its people and surroundings. It means engaging with the world and continually evolving your perception of it.

[S notes:<< you are describing a methodology for reading a city]

It involves being open to unexpected opportunities that arise IN unfamiliar streets, IN shadowed corners, IN familiar spaces, IN chaotic streets, IN the spaces in-between, IN spaces of certainty, IN neighborhood park, IN museum courtyards, IN crowded markets, IN city squares, IN quiet side streets, IN leisure spaces, IN shared spaces, IN spaces full of people, IN parking spaces, and open spaces. There are PEOPLE always in a hurry, PEOPLE who sing to themselves, PEOPLE who take detours, PEOPLE who carry notebooks, PEOPLE lost in their thoughts, PEOPLE who bike everywhere, PEOPLE who dream vividly, PEOPLE who miss their hometowns, PEOPLE who never stop questioning, PEOPLE walking alone, PEOPLE who adore symmetry, PEOPLE who enjoy getting lost, PEOPLE who love surprises, PEOPLE who stay up late, PEOPLE who speak with their hands, PEOPLE who feel out of place, PEOPLE walking slowly, and PEOPLE speaking many languages, shaping the spaces we inhabit. Perhaps we take these spaces for granted, moving through them daily withou t much thought. But maybe we can learn to see them differently: TO SEE the long way home, TO SEE the stories in gestures, TO SEE the endless possibilities, TO SEE the rhythm of the city, TO SEE the connections, TO SEE the hidden textures, TO SEE the passing time, TO SEE the absurdity, TO SEE the hidden shortcuts, TO SEE the unexpected, TO SEE the structures, TO SEE the stories, TO SEE the choices in how we move, TO SEE the city’s edges, TO SEE the city as a game, TO SEE hidden playgrounds, TO SEE new paths, TO SEE the extraordinary in the ordinary, TO SEE the absence, TO SEE with the greatest precision, TO SEE what’s written in the street. When we learn to see, nothing will stop us from reimagining these spaces anew—other uses, other functions, other possible ways of navigating them. I believe the first step is to pay attention.

It started this summer, with a pair of binoculars I bought at a market for three euros. Totally absorbed, I spent hours on Yana's balcony, observing the rooftops of Sofia — textures, antennas, and edges. Gradually, fragments of the city revealed themselves. Serendipity played a role in these observations, and I couldn’t have been happier, as I noticed things that usually go unnoticed. The binoculars became my tool for "reading" the city and found a permanent place in my routine. [How so, it would be interesting to describe the experience of seeing anew through this new "lens". Please describe a particular moment. What is happening? The reader can then share the immediacy of that experience] I became obsessed. Through them, I observed Sofia, Warsaw, Frankfurt-Oder and Słubice, Rotterdam, and Groningen. It fascinated me how even the simplest tool, with its inherent limitations, could open us to unexpected opportunities. How narrowing the field of vision, allows for looking at the city piece by piece and brings a specific fragment to the front.

I built a camera obscura, large enough to step inside and place it in public space. I was curious to see how our perception changes when we view an image upside down. Would we notice something extraordinary in what we see every day? Unfortunately, the costs of constructing such a device overwhelmed me. Instead, I realized this idea within the confines of my room. Using cardboard and the properties of light, I transformed my room, already positioned on the street, into a camera. I darkened the entire space, leaving a pinhole to create an inverted image. On my table, I saw a fragment of the bridge where train tracks once ran. At that moment, I knew I was inside the camera. The projection was smaller and blurrier than I expected, yet I observed the bridge fragment with a level of attention I’d never given it before. For two years, that view had been the first thing I saw when opening my door. It wasn’t until I saw it upside down that I truly paid attention. [where did you make this?]

I continued observing my surroundings. For days, I sat in a square, observing at specific times. I watched my street through the frame of my window. I observed the street corner framing it from a café. I built a device — a tube – for reading the city. I watched the city through a paper frame, a camera, and a film camera lens. I became an expert observer.

But do we really need tools for this? [The other question is: what do you gain from using such tools? Why is it satisfying for you to frame? What happens when you crop? What happens when you frame?] Isn’t curiosity and simply being in a space, observing what surrounds us, enough? Devoting time and attention seems sufficient, yet so much escapes us and remains unnoticed. We cannot take in the entire city at a glance; we need separation and pauses to interpret what we see. Otherwise, everything becomes a continuous stream of unprocessable information. What matters to me is how this observation can contribute to our active participation in a space. It is in this context that I want my magazine to become a frame for urban observations and situations. And thats also what I mean by a tool.

I decided to narrow my focus, choose a fragment, and frame it for closer examination. Inspired by Alison Knowles's 1967 poem The House of Dust, [<describe that text in a sentence or so] I developed a script to list various locations, people one might encounter there, and observations. The script randomly combined entries from each category, generating statements that I treated as prompts for further focused observation. [Note: With the script, you are creating another technology for looking (like the camera obscura, binoculars and tube). It seems to be different to mapping a space. It is about apprehension of a space, more than about its relation to other spaces. Are these devise about providing an encounter with a particular space? It is interesting how the aesthetic that is developing mirrors early film and photography. What do you think the relation is, for you? (there are no wrong answers here).]

Thus, the first issue of Fragments Magazine is dedicated:

FOR PEOPLE who always carry a notebook

TO SEE the choices in how we move

IN open spaces

(I searched for photographs in archives and video materials from early cinema because I wanted to work with these fragments. I wanted to use cropped images to illustrate the choices in how we move, and I got lost in a sea of colorful frames from Scheveningen in the Twenties.)

- ↑ The Production of Space, Henri Lefebvre

- ↑ Silent City Films (early 20th Century): https://library.fiveable.me/city-in-film/unit-2/silent-era-city-films-urban-modernity/study-guide/uxbdekHKTNFoe9U4

Outline

Chapter 1

What does it mean to read the city? - Part 1

Tools for reading the city - Part 2

- The Production of Space, Henri Lefebvre

- Smooth City, René Boer

- Creative Processes in the Human Environment

Chapter 2

Methods for spontaneous encounters - Situationists approach and the art of chance

- The term "society of the spectacle”, introduced by French theorist Guy Debord in his book The Society of the Spectacle, describes a society influenced and dominated by images, advertising, and media, where appearances are more important than authentic experience. Following this thought I would like to dive into "Report on the Construction of Situations" by Guy Debord (1957). In this manifesto, Debord explains the concept of "constructed situations" encouraging interventions in urban spaces that provoke new ways of seeing and interacting with the city.

- This chapter is a space for critical reflection on how I can activate the magazine in public spaces.

Chapter 3

Scripts or unintentional adventures? - What documentaries taught me?

- In this context, the book Why I Make Documentaries by director Soda Kazuhiro is especially important to me. In it, he discusses observational filmmaking, speaking about rejecting the idea of preparing a script before shooting and instead creating a story based on discoveries that happen during the process. He also talks about the unexpected discoveries, encounters, and unintentional adventures that the observational filmmaking approach brings. I agree with not strictly adhering to a script, as it’s so easy to cut out even the most interesting scenes simply because they don’t fit a narrowly defined topic. On the other hand, I believe that a script that remains open to interpretation can actually enhance imagination and open up new ways of exploring public space. I believe that scripts and unpredictable encounters can complement each other, and I’m curious how I could explore this further.

- There was this film that I saw during the French film festival - where two characters decided to walk always in a straight line —- so they had to walk on top of the car cause it happen to be on the way.

Chapter 4

Cutting, fragmenting, rearaging - as a way of rewriting our spaces

- Dziga Vertov – Man with a Movie Camera (1929) - This documentary film captures a day in the life of a Soviet city through the eyes of a "movie camera man.” There is no one plot, the film maker is experimenting with montage techniques. Vertov’s approach presents the city as a dynamic, interconnected system.

- Drawing from these examples I will reflect on my practice, which incorporates image-making. I still record and photograph a lot, but then I use this footage to translate it into a collage. fragmenting and rearranging as reimaging. A lot of this happens in my notebook

Intro

With this paper, I dedicate time to moving through various places and observing them with curious eyes. It brings together fragments from my notebook, making the writing a dialogue with walking, collecting, and rearranging fragments. This text is an opening to the unexpected, to accidental discoveries and observations. I aim to uncover alternative ways of seeing and relating to our cities. I seek ways to open to different experiences, searching for unpredictability and surprises in the city, exciting connections, and interactions with others in shared spaces.

Chapter 1. What does it mean to read the city? - Part 1

Reading the city isn’t just about observing it from a distance. Reading a city means being genuinely curious about its people and surroundings. It means engaging with the world and continually evolving your perception of it. The language of the city lies in the situations and unexpected opportunities that arise. We read it with our eyes, ears, and feet

IN unfamiliar streets,

IN shadowed corners,

IN familiar spaces,

IN chaotic streets,

IN the spaces in-between,

IN spaces of certainty,

IN neighborhood parks,

IN museum courtyards,

IN crowded markets,

IN city squares,

IN quiet side streets,

IN leisure spaces,

IN shared spaces,

IN spaces full of people,

IN parking spaces, and open spaces.

There are

PEOPLE always in a hurry,

PEOPLE who sing to themselves,

PEOPLE who take detours,

PEOPLE who carry notebooks,

PEOPLE lost in their thoughts,

PEOPLE who bike everywhere,

PEOPLE who dream vividly,

PEOPLE who miss their hometowns,

PEOPLE who never stop questioning,

PEOPLE walking alone,

PEOPLE who adore symmetry,

PEOPLE who enjoy getting lost,

PEOPLE who love surprises,

PEOPLE who stay up late,

PEOPLE who speak with their hands,

PEOPLE who feel out of place,

PEOPLE walking slowly,

PEOPLE speaking many languages,

shaping the spaces we inhabit.

We often take these spaces for granted, moving through them daily without much thought. But what if we could learn to look at them differently:

TO SEE the long way home,

TO SEE the stories in gestures,

TO SEE the endless possibilities,

TO SEE the rhythm of the city,

TO SEE the connections,

TO SEE the hidden textures,

TO SEE the passing time,

TO SEE the absurdity,

TO SEE the hidden shortcuts,

TO SEE the unexpected,

TO SEE the structures,

TO SEE the stories,

TO SEE the choices in how we move,

TO SEE the city’s edges,

TO SEE the city as a game,

TO SEE hidden playgrounds,

TO SEE new paths,

TO SEE the extraordinary in the ordinary,

TO SEE the absence,

TO SEE with the greatest precision,

TO SEE what’s written in the street.

When we start to look at them differentky, nothing will stop us from reimagining these spaces anew and other possible ways of navigating them.

In cities, there are far more unexpected connections than one might think. But sometimes, noticing them takes time. Waiting for the unexpected to happen might seem boring to some people. When we set out to find it but fail to see it, it can frustrate us. However, waiting in this context is important. Waiting is a part of reading the city. By waiting, we allow ourselves to get bored—and that boredom can lead to unexpected, creative ideas. Waiting is a resistance against efficiency at all costs. Reading the city isn’t always equally exciting. Reading the city requires time and attention. It involves getting lost, observing in the rain, or taking the long way home. Not everything has to be productive, smooth, or predictable—and that’s what makes reading the city so fascinating.

René Boer’s concept of the “Smooth City” ties into this idea. He describes the growing tendency in urban environments where experiences become increasingly seamless. We have services that deliver groceries to our doors, dating apps, and smart solutions that provide us with comfort, but they also create a frictionless environment. While everyone deserves a safe and clean environment, such conditions gradually eliminate opportunities for serendipity, potential, encounters, and all those unexpected events that cannot be planned in advance. This raises an important question: what kind of cities do we really want? Do we prefer a predictable, frictionless environment, or do we want to embrace random chances? Personally, I long for a city where I can be myself, where I enjoy conversations with strangers, where I discover new paths, where not everything is reduced to the same ideal, polished appearance—a city created by people and therefore full of potential.

This magazine may seem a bit messy, but this messiness in unpredictability can bring unexpected connections. And this is what the act of making this magazine public and publishing it outdoors call for. It seeks to decode the language of the city and by actively existing in public space, it becomes a tool for that, knowing that this act is an unfinished process. The image of the city is ever changing, its never complete.

To focus this exploration, I decided to narrow my scope: choose a fragment and frame it for closer examination. Inspired by Alison Knowles’s project The House of Dust, in which she used code to generate short poems that she later translated into physical houses, I developed a script, listing various locations, people one might encounter there, and observations. It then randomly combines entries from each category, generating statements that I treated as prompts for further focused observation.

Thus, the first issue of Fragments Magazine is dedicated:

FOR PEOPLE who always carry a notebook

TO SEE the choices in how we move

IN open spaces

I think that limitation and a certain imposed boundary can be very creative. Through the script, which selected and combined three entries from a wealth of street observations, a relationship between them emerges. And in a way, this automatically opens up new possibilities. This was initiated by the computer, but what happens next depends entirely on my interpretation.

Tools for reading the city - Part 2

As much as I am captivated by the moving image, cities are not only visual. Like Lawrence Halprin wrote: “Architecture alone does not make a great street anymore than a fine stage set makes great theatre. The two depend, finally, on what happens and what interactions occur; what they generate in the human experience” (‘Creative Processes in the Human Environment’). In this context I'm interested in how even the simplest tools, which impose certain limitations, can open us up to unexpected opportunities.

I’m curious about translating what film works with into a system for exploring physical space. Film deals with scripts, continuity, speed, time, rhythm, and frames. They use cutting and rearranging pieces. I’m curious to use these elements as tools for decoding the language of the city. I want to allow an interplay between what is perceived and what can arise and come into view.

This fascination with framing started this summer, with a pair of binoculars I bought at a market for three euros. Totally absorbed, I spent hours on Yana's balcony, observing the rooftops of Sofia—textures, antennas, and edges. Gradually, fragments of the city revealed themselves to me. Serendipity played a role in these observations, and I couldn’t have been happier, as I noticed things that usually go unnoticed. The binoculars became my tool for reading the city and found a permanent place in my routine. With a newfound interest, I scanned buildings, gliding along their lines. They made me notice houses that look like they are hugging the one in the middle. Passersbys entered and exited my frame, suddenly, the city became full of surprises. I became obsessed. Through them, I observed Sofia, Warsaw, Frankfurt-Oder and Słubice, Rotterdam, and Groningen. It fascinated me how even the simplest tool, with its inherent limitations, could be an opening for so many surprises. What I mean is all th ethings I have seen before but ignored. I find it intresting how narrowing the field of vision, allows for looking at the city piece by piece and brings a specific fragment to the front.

Inspired by that, I decided to build a camera obscura large enough to step inside and place it in public space. I was curious to see how our perception changes when we view an image upside down. Would we notice something extraordinary in what we see daily? Unfortunately, the costs of constructing such a device overwhelmed me. Instead, I realized this idea within the confines of my room. Using cardboard and the properties of light, I transformed my room, already positioned on the street, into a camera. I darkened the entire space, leaving a pinhole to create an inverted image. On my table, I saw a fragment of the bridge where train tracks once ran. At that moment, I knew I was inside the camera. The projection was smaller and blurrier than I expected, yet I observed the bridge fragment with a level of attention I’d never given it before. For two years, that view had been the first thing I saw when opening my door. It wasn’t until I saw it upside down that I truly paid attention.

The camera obscura flips the image, and much like binoculars, it allows me to see it with a renewed sense of interest. I read the city upside down. It reminds me of my summer Sunday tradition that I used to have when I was living in a room with access to the garden. I would go out into the garden, lie down on a bench and look at my Dutch house upside down. It brought me such joy that when my friends came over and we had dinner in the garden, we’d do it together. We’d lie on the two benches of the picnic table, simply observing, passing a cigarette under the tabletop.

I continued observing my surroundings. For days, I sat in a square, observing at specific times. I watched my street through the frame of my window. I observed the street corner framing it from a café. I built a device — a tube – for reading the city. I watched the city through a paper frame, a camera, and a film camera lens. I became an expert observer.

The most important function of these framing tools is that they open possibilities without determining what exactly will emerge. Through constraints and limits, unexpected connections arise. I continued this by juxtaposing different combinations. Based on the aforementioned script inspired by The House of Dust by Alison Knowles, I prepared a script that selected entries from various categories and combined them to create prompts for participants in my workshop to build their own paper tools that invite looking at our surrounding differently. Tools we have built included:

A TOOL

FOR people who love surprises

TOO SEE the hidden textures

IN unfamiliar streets

A TOOL

FOR people who speak with their hands

TOO SEE the city as a game

IN the shadowed corners

A TOOL

FOR people who bike everywhere

TOO SEE the stories in gestures

IN shared space

A TOOL

FOR people always in a hurry

TO SEE the passing time

IN an open park at night

A TOOL

FOR for people who adore symmetry

TO SEE the stories

IN a place full of people

Participants using the properties of paper prepared simple tools that, guided steps to take. While still open to interpretation, they enabled specific activities to occur in space. For instance, I drew by lot a prompt:

A TOOL

FOR people who always carry a notebook

TO SEE the choices in how we move

IN open spaces.

I created a sheet with step-by-step folding instructions. Once folded, it could serve as a bookmark in a notebook. When unfolded into a fan shape, it revealed instructions for moving, such as: find corridors between people or notice how space is opening and closing. Each segment displayed a different suggestion for navigating the space.

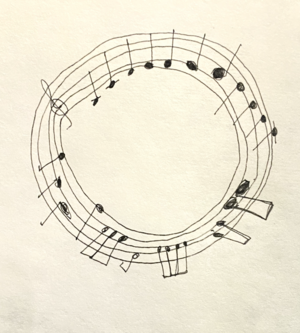

I became intrested in scoring, that share simmilar function. By visually communicating processes happening over time, they allow for the process to constantly evolve. Scores constitute a system of symbols. Elements like time, space, rhythm, and their combinations are presented graphically, visualising a process and influencing it. Scores can be more controlling or more suggestive, but they are always tied to a process and involve certain constraints and limits. For example, the score accompanying Charles Amirkhanian's performance did not dictate exactly how it should be interpreted. It consisted of drawings that could be freely interpreted by musicians, fueling the performance. This approach was not limited to professional musicians; anyone could participate as long as they interpreted the images in their own chosen way. This example demonstrates how playing with chance and control, rather than imposing something, can energize participants' performance. In this case, the score became an opening for chance.

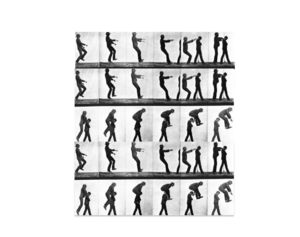

How does this translate to different fields? Going back to the focus of this magazine ( TO SEE the choices in how we move) How can movement be visualized and influenced in a graphical form? There is a difference between graphical representation and the action that results from it. But one informs the other.

A zoetrope moves individual frames, animating them into smooth motion. But when I look at it as a flat image, it becomes a graphic representation of that movement over time. It reminds me of musical notation. What if I were to record movement using symbols, similar to a musical staff? Instead of a composition, I could record a walk...

The zoetrope, by animating frames arranged in a circle, plays with continuity and repetition. Similarly, I could write notes on a staff that loops into a circle, suggesting that this segment should be played repeatedly, over and over. By playing with this looping, we could create a notation for a walking choreography where you continually turn only to the right, or only take narrow streets. Frames, continuity, repetition.

Once again, I find something surprising and exciting in the imposed constraints.

New fragments

In [title] I reflect on how we perceive our direct surroundings. Perhaps we take these spaces for granted. But maybe we can learn to look at them diffrently to see those spaces as something that we make rather than discover. How can the way we look at our surroundings contribute or inform our transformation of it?

Through the following chapters, I delve into the tools that shape our vision, the methods that encourage spontaneous encounters inspired by the Situationists, and the role of attentiveness. Drawing insights from documentaries and early cinema I aim to uncover ways of paying attention to our surroundings.

Outline update

Chapter 1:

"The process of looking and walking in the city with new and critical eyes already creates entirely new expectations and experiences."

I would like to share what I discovered by navigating the city in this manner, observing the city with attentive eyes. This chapter tells the story of how, through my exploration of the city with a camera, I stumbled upon a lost cinema... and how I created a performance on the building's façade.

Key Themes:

Psychogeography: Understanding urban spaces through spontaneous, unplanned exploration.

Patrick Keiller’s Approach: How walking and film-making can shape our understanding of the city.

Representation vs. Reality: How the cinematic gaze aligns with or diverges from the lived experience of urban space.

Questions to take to the second chapter: How do we cultivate curiosity when exploring familiar places?

Chapter 2

Subjective Experience and familiar places

How do personal and collective memories interact with physical spaces to create emotional geographies?

In this chapter, I delve into how subjective experience shapes our perception and engagement with the world. I discuss how memories shape our relationship with spaces and how we interpret them emotionally.

Key Themes:

Warsaw Walk: A personal journey through the city - the role of memory in shaping the relation with the city.

I begin my walk from the Plac Trzech Krzyży, pass a building with three façades, head towards Mokotowska, and end at the Kino Luna, reflecting on the fate of Luna cinema temporarily closed...

Stewart Home, the English artist and writer who in 1992 revived the London Psychogeographical Association, states:

“For me photography is most alluring when both the person behind the lens and what is being photographed self-consciously manifest their subjectivity. Traveling across ‘Britain’ to discover ‘America’ is only one of the many ways in which such subjectivity might remake the world in both photographic and material form. . . . The psychogeographer . . . knows that the world cannot be recorded, it can only be remade.”

Sally Santon: Her exploration of the unexpected in urban spaces

Chapter 4

Cutting, fragmenting, rearaging - as a way of rewriting / reimagining our spaces

questions: what is a role of imagination in understanding our spaces?

Can psychogeography serve as a tool for resistance against homogenized urban planning?

for the Chapter1

Moving through the city where my intuition takes me, navigating the city in various ways, I understand as a method of decoding the language of the city. While walking, I discover new meanings and stories that it hides. The act of walking in the city and looking with curiosity and attention already generates completely different perspectives.

This summer, I participated in a summer school held in a twin city: Frankfurt Oder and Słubice, and that's how I ended up in this place. I spent two weeks in the twin city. From the moment I arrived, I walked with a small camera, which my parents once used to record our birthdays. Now, this very camera became my tool for discovering the city. The camera, as well as walking, drifting, which took me to random places much like the dérive proposed by the Situationists. Dérive involved wandering through the city without a specific goal, only guided by how the environment influences emotions and behavior. The aim was to break the routine and create new, spontaneous ways of interacting with the city. Participants in these walks explored how specific places and the city's layout affected their behavior and feelings. This allowed people to imagine urban spaces anew, envisioning new functions for these places beyond the utilitarian or commodified ones. In my case, my contemporary drifting was not aimless wandering; it had a purpose. I wanted to reach new places to better understand the twin city. I wanted to find something I could tell in a short film.

“Psychogeographic writing can be thought of as an alternative way of reading the city. Wilfried Hou Je Bek calls it “the city-space cut-up.” Just as William Burroughs and Brion Gysin cut and reorganized newspaper texts to reveal their implicit content, so too psychogeographers decode urban space by moving through it in unexpected ways.” (O'Rourke, 2020)

I want to tell how, by walking through the city and discovering it in fragments through my camera, I found the lost cinema. I don't know Słubice well; I was born and raised in Warsaw. I'm telling this story from the perspective of someone who doesn't live there, but I was intrigued by the history of this place, and this abandoned cinema became dear to me.

And that's how I got to know the place better, walking through it. By walking, I learned things that articles on the internet didn't reveal. The context of these cities was fascinating, as they developed simultaneously and together they are much stronger. Before the war, it was Frankfurt Oder; after the war, the right side of the river became the Polish part. The two cities are now divided by the river and connected by one bridge. Electronic equipment is bought on the German side, while the market it is common to go on the Polish side because it’s much cheaper. Waiters often speak both languages fluently, and on the Polish side, you can pay with both currencies. Every day, I walked along the same path, passing a square, a small park, a parking lot, then crossing the bridge, and immediately after the bridge, turning left to Zukunfpplatz, where I met the rest of the people from the summer school. What amazed me the most was the 16 hairdressers on one street right next to the bridge. Prices are still lower, so Germans cross the bridge and go to the hairdresser on the Polish side. It is still worth it, even though hairdressers have sprung up next to each other like mushrooms after the rain. I walked and observed. I wandered where my intuition led me. Actually, with no plan, not knowing what the new city would reveal to me. My feet turned out to be excellent at reading the city. But the most helpful was the small camera. The collected footage created an increasingly richer image of the city in my eyes. It was wonderful how the film made me braver, more willing to talk to people and ask them about the specifics of the city and life there.

Patrick Keiller, filmmaker, psychogeographer, and writer, believes that film changed how we think about the city. He says that the image becomes a way to investigate. Indeed, walking is also key in his film-making process. In his book review, Michael Pattison writes that Keiller mentioned that at least two of his essays were created when the artist tried to find a place he noticed through the window of a passing train.

I wonder how films construct the image of the city, and how this influences our understanding of urban life. Does it align with or diverge from the lived experience of urban space? Collecting frames from this city and searching for threads to tell in this short film so boldly led me to completely new places. I met many people and learned many stories. Among others, a man from the local radio in Frankfurt Oder, who told me how Polish women created a broadcast about the difficulties related to the abortion ban in Poland. What could not be broadcast on the Polish side, could be highlighted on the German side. This made me realize, how can I tell something about this place, I am only passing through. Especially after the conversation with the very polite man from the market and many others who spoke about the difficulties of life there, I understood that I had no idea what it means to live in Słubice...

Realizing that I am speaking from the position of someone who was only in the city for two weeks, I wanted to express how I feel about this place and what it symbolizes to me. I usually returned to the dorm on the left side of the street, passing by a beautiful old building with a plywood-covered entrance. For so many days, I passed this building, but never really paid attention to it. Once, coming back on the other side of the street, I saw it in its entirety. On the top was the inscription NO PAST, which puzzled me as to what it meant... Then, I noticed the missing letters, and the letters that had fallen off revealed KINO PIAST. (Cinema Piast). I was intrigued by what had happened to these letters. I thought it was a remarkable coincidence that the letters had fallen off, leaving the message NO PAST.

The architect and photographer Lorenzo Servi, whose book I bought in Berlin, organizes walks and workshops with the intention of attentive observation. One of his ways of drawing attention to something and giving it new meaning is to remove the object from its context. This allows one to look at it with new eyes, with a fresh perspective. In this case, it was a bit different. The inscription NO PAST was already taken out of context, but when I noticed the missing letters, it suddenly revealed another meaning, emphasizing the rich history of this place, contrasting with the printed letter inscription. I became interested in this and got in touch with a local journalist to investigate the topic. She, in turn, directed me to an architect who had extensive knowledge about this building. By chance, he responded to my email, and the next day we met in front of the cinema. I learned from him what character this cinema had. Apparently, people loved it, even though from the stories it seemed that the smell was awful. It was probably the dampness caused by the flood that occurred there. However, the cinema was still popular. They supposedly showed great movies. It was run by a man who, during the day, sold flowers in front of the entrance to pay for the projection costs. The changes that occurred in the city ruined it. It's so sad that the residents lost this building. Having only one week left, I felt the desire to bring back the audience to this abandoned building.

In this whole adventure and my drifting through the twin city, the act of walking, observing, and documenting was not meant to present an objective truth about the place, if such a thing even exists, but rather to build a relationship with the place. I know I was there for a very short time, but I didn’t want to just document what I had learned; I had engaged with the fate of the Kino Piast. The cinema’s interior was ruined. Only the façade remained. On both sides of the entrance doors were empty frames where once film posters had hung. It begged to have posters placed in those empty frames again. I organized a performance with a girl from Amsterdam I met there. We prepared a text with memories from people who remembered the cinema and read it in front of the building. The event was accompanied by music and shadow play on the building's façade. We cut shapes out of paper and attached them to sticks. I found old sheets in a flea market hall, and we used them as a background for the shadow projection. Someone had a lamp strong enough for the shadows to be clear. The empty frames on both sides of the entrance doors were filled with new posters inviting passersby to the shadow show. A crowd gathered and participated to create a projection together. It was a beautiful experience to bring an audience back to this cinema, even if only for one evening.

Cities and specific places are not rigid and unchanging. They can be imagined anew through our subjective involvement. And I understood that my subjective perspective is central in how I interpret my environment and interact with it. Lefebvre (1991, p. 73) states that "Space is neither a ‘subject’ nor an ‘object’ but rather a social reality—an outcome of a sequence and set of operations, and thus cannot be reduced to the rank of a simple object."

The tension between what is possible and imagined, and what is realized, holds transformative potential, as long as we navigate its contradictions and hidden possibilities. Just like Keiller's film exploration attempts to reach beyond representation into the realm of action.

"The real work begins, then, in forming a bridge between the conceivable and the actualised. And that bridge might require something beyond the cinematic" (Pattison, n.d.).

Returning to the camera as a tool to investigate the city, I believe it has an impact not only on how we understand these places but also on how we change them. It retains the capacity to surprise, to reveal contradictions, and to invite change.

References:

O'Rourke, K., 2020. Psychogeography: A Purposeful Drift Through City Spaces.

Pattison, M., n.d. Keiller’s Cinematic Walks: Finding Beyond Representation.

Lefebvre, H., 1991. The Production of Space.