User:Catalina/Project Proposal

Title

Sky Islands: a time machine of the Andes Mountains

What do you want to make?

This is an exciting story about a group of researchers that has been studying long term climate dynamics and the evolution of the ecosystems in the Northern Andes for more than 50 years. Their studies have been focused on understanding vegetation dynamics in present and past times (see studies from A. Cleef, T. van der Hammen, H. Hooghiemstra and co-workers). After many years of studying pollen fossil, aging materials, sedimentation rates, current species of plants, different type of ecosystems and its geographical distribution (among others), they found unique long fossil pollen records that cover the last 3 million years history of the Andes Mountains. (Hooghiemstra 1984; Bogotá et al., 2011; Groot et al., 2011; Torres et al., 2005, 2013). They also found a pathway to make spatial reconstructions through time about the top highest Andean ecosystems: the páramos (Van der Hammen,1974, Flantua et al., 2014, Flantua & Hooghiemstra, 2017).

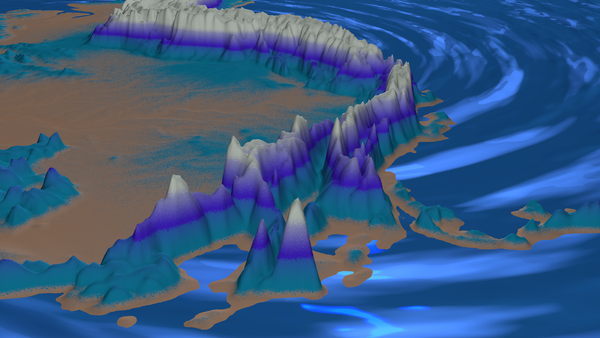

Imagine the páramos as highly species rich ecosystems which are currently restricted to mountain tops in the northern Andes where they resemble an archipelago of isolated islands. However, in the past they dominated large surface areas throughout the Northern Andes. Driven by large scale cycles of climate change, the páramo ‘sky islands’ shifted altitudinally along the mountain slopes, influenced also by the topography that causes a complex spatial mosaic of fragmented (small) and connected (large) páramo areas. During cold conditions, the low elevational position of the páramos cause the many isolated Páramo islands to fuse, while during warmer conditions the páramos formed isolated archipelagos in a connectivity dis-connectivity dance, a mechanism described as the ‘flickering connectivity system’ (Flantua & Hooghiemstra, 2017).

Sky Islands: a time machine of the Andes Mountains is an exploration on how to display the above scientific information using digital art, 3D animation, and data visualization as contemporary tools to imagine ecosystems in the past. The challenge is to find a pathway of telling the dynamic history of the páramos of the Northern Andes in a visual and revealing form. This project is a science, art, and technology convergence, integrated into an innovative education model that explores theories from different disciplines with the aim to engage researchers, students, and general audiences. The purpose of the visualization is to make them understand the importance of these natural evolution process that took millions of years in the Northern Andes, for our current understanding. In more detail, this project will envision how the shifting elevational distributions of the Andean ecosystems was caused by cold and warm conditions driven by long term climate cycles, called the Milankovitch cycles (Muller et al. 1997) and how the diversification of species increased as a result of these cycles, but also how these ecosystems which process of evolution expend thousands of years is being deteriorated in just hundred years of devastating human activity.

How do you plan to make it?

The complete process includes pre-production, production, and post-production following the next steps.

A. Pre-Production: Storytelling and timeline The storytelling of Sky Islands: a time machine of the Andes Mountains is based on publications and meetings with UvA’s researchers to understand and transform their results into a storytelling which follows a timeline of the last 3 million years (latest Pliocene, Pleistocene, Holocene and Anthropocene geological periods). This will be composed of three parts:

1. There is a macro-scene from outside the Earth showing the glacial (the coldest periods) and interglacial (the warmest periods) Milankovitch cycles, called ‘eccentricity’, ‘obliquity and ‘precession’. These cycles caused a cyclical variation in the solar radiation reaching the Earth, which strongly influenced climatic patterns around the globe. The páramos have been shown to be very sensitive to these cycles.

2. There are two close-ups in the Andes mountains:

a. A general scene from the Northern Andes to visualize and understand the main vegetation dynamics. This mechanism is called Flickering Connectivity System and shows how the Andean ecosystems (páramos and Andean forests) shifted up and down along the slopes. Also, the páramos expanded and contracted to form archipelagos of isolated islands, also called ‘sky islands’. This camera point of view is mirroring the macro-scene from outside the Earth but shows the same process in more detail within the mountains. There will be a clock showing the time-machine, and extra information about the altitude of the main three Andean ecosystems and a legend that explains the used colors (temperature and ecosystems).

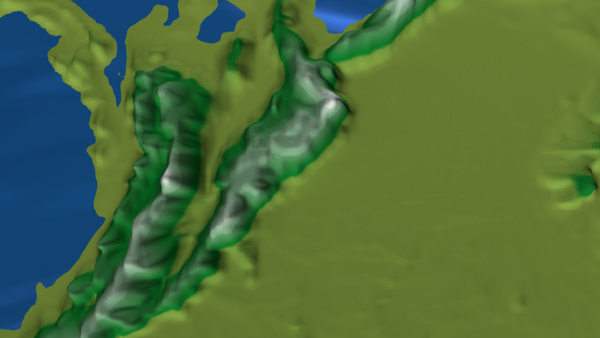

b. A close-up at the central mountain chain in Colombia to show changes in more detailed perspective on how the páramo archipelago changed over the last 2.6 million years, the Quaternary. For this part, we chose six scenarios as the most representative snapshots of the whole storyline. These scenarios will be repeated in similar conditions of glacial and interglacial periods but in different moments of time during the last 2.6 million years.

• Scenario 1: Pliocene. The páramo biome had evolved during the previous millions of years when climate had only fluctuated little; the páramo was poor in species • Scenario 2: Pleistocene. Interglacial (Warm conditions). 1 million years before present, Alnus tree entered into the northern Andes. • Scenario 3: Pleistocene. Glacial (cool stadial conditions). 480.000 years before present. The tree Quercus enters into the Northern Andes. • Scenario 4: Pleistocene. Glacial (mild interstadial conditions). X, Y, Z years • Scenario 5: Holocene. Interglacial (warm conditions). X, Y, Z y years • Scenario 6: Interglacial in the Anthropocene, deforestation, actual conditions, today.

B. Production: Illustration Design + Revision and Animation + Revisions

I am making a 3D animation using Cinema 4D and VUE Xtreme. For final renders, I am using After Effects and Adobe Premier. To generate the real landscapes of Andes mountains in Cinema 4D and Vue Xtreme, I am using high-resolution Digital Elevation Models (DEM at 30m and 90 m of resolution). To design plants, I will use VUE-Plant Factory. General and technical steps are modelling, texturing, lighting, animating, camera animating and rendering.

C. Post-Production: Rendering + Revisions and Final editing + Revisions This final step is dedicated to make the final renders and edit the composition, effects and color correction.

D. Installation The final outcome will depend on facilities for materials, but I am currently preparing the following three options:

1. Immersive 360 degrees’ video installation, the half screen will display the cycles outside of the Earth and the second half, the process happening in the mountains as a mirroring or a reflection of the Sun-Earth cycles.

Inspirations

http://jessieboylan.com/ngurini-searching/

http://www.tamschick.com/en/projects/time-machine/

https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=6&v=hyzoQ8jagwI

2. A video installation using two confronted screens, but in this case, one screen will display the cycles outside of the Earth and the second screen the process happening in the mountains as a mirroring or a reflection of the Sun-Earth cycles.

3. A five minutes editing for film and screening. Additionally, the visualization will be integrated with additional explanations provided by researcher’s interviews. The results will be available in an open access domain, e.g. on the IBED server, and will also be part of the Installation.

What is your timetable?

| Steps Process | 4 Trimester | 5 Trimester | 6 Trimester |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Production: Storytelling and timeline | x | ||

| Production: Illustration Design + Revision and Animation + Revisions | x | x | x |

| Post-Production: Rendering + Revisions and Final editing + Revisions | x | ||

| Installation | x |

Why do you want to make it?

One of the reasons I decided to explore digital arts as a biologist, is that a) there a great concern about the current ecological crisis we are testifying and b) I have always been interested in using contemporary tools for visual communication to integrate different disciplines and their visions and results. I am totally convinced we can inter-cross these disciplines to re-establish the lost awareness that will remind us why we need to protect and respect the natural environments on Earth.

In the times we are living today, the global warming is affecting not only our human species but also the entire range of species and inhabitants of the planet Earth. For this reason, this project seeks to envision how the past times in the Andes mountains took more than three million years to let developed an impressive diversification of ecosystems and species in the páramos. However, human impact during the last 500 years, and specially the hundred years after industrialization, has had an overwhelming capacity to drive to extinction unique species that have been evolving and diversifying for millions of years. This visualization not only opens a door to travel in a “time machine”, from the late Pliocene to the Anthropocene, but it is also a first step toward opening minds and creating awareness of the importance of evolution in the South American Andes ecosystems and its biodiversity. Furthermore, it also aims to incept a question on how we can change the future and our relationship with the Andes in a way to mend the disaster we have been creating.

Finally, I consider this Art-Science collaboration project first of all very close to my soul, and secondly an incredible opportunity to communicate visually the results reached by my own professors and colleges. First as a biology student and later as professional and pollen analyst, I had the opportunity of being part of their research group between 1998 and 2009, and now I have the amazing opportunity to be both a visual artist and biologist. I am sure the resulted outcome not only will help students to better understand the dynamic history of the páramo ecosystem and high mountain ecosystems in general, but it will also be relevant for a very large share of public audiences including scientists, universities, new media artists, schools, policymakers, and governments.

Who can help you or how?

This project is in collaboration with the research team of Paleoecology at the Institute for Biodiversity and Ecosystem Dynamics (IBED), University of Amsterdam, which is supported in the scientific part by Suzette Flantua Ph.D. and Professor Henry Hooghiemstra. They will provide advice in science research, data and publications that will be the core of the visualization script and story. Also, I will have the support of Arts advisors at Piet Zwart Institute as Simon Pummell, Barend Onneweer, David Haines, Ine Lamers, Javier Lloret, Marloes de Valk and several professors at Willem de Kooning Academy for data visualization work.

Relation to previous practice?

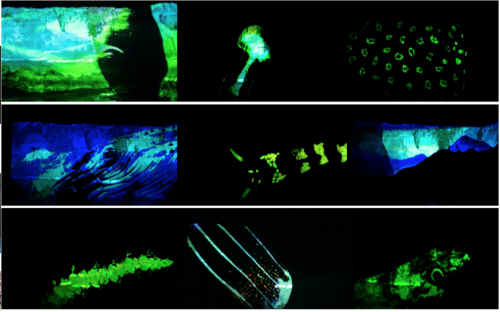

As a biologist, I have been working in different research teams that investigate the past, present, and future ecosystems in Colombia. My interests as a researcher have been to understand how the changes in climate have been modifying plants and vegetation through different periods of time and space but also how to communicate that in a visual form. Today, my interest as a visual artist is to explore how to transform the knowledge created through the lens of science in a visual art piece using 3D animation. For the reasons above, I have been exploring life plant installations, video mapping projection, and photography of nature. Some of the projects I have done before took shape between 2011 and 2017 and were supported by many artists and technicians at the University of California- Santa Cruz, Piet Zwart Institute, Science Park (UvA) and the Eye Filmmuseum.

(More info here http://www.catalhinagiraldo.com/art-installations)

Relation to a larger context?

In a larger context sense, the piece would be outlined inside the conceptual movement of artists exploring the metaphorical language of Planet Earth which started in the 1970s, like “Planet Earth in Contemporary Electronic Artworks” and “Environmental Art”, which expression coined as an umbrella term to encompass Eco-Art/Ecological Art, Ecoventions, Land Art, Earth Art, Earthworks, and Art in Nature (Knebusch, 2004; Bower, 2010). To bring some examples for Environmental Art, there are over 150 artists, and close to 22 scientists and Science & Arts collaborative projects, organizations, programs, and residencies focused on this Eco-Art movement around the world (The Greenmuseum, 2010). A number that has been increasing with the current ‘Art in the Anthropocene”, a massive trans-disciplinary movement of artists, designers and scholars exploring the symbolic language of the Anthropocene (Anthropocene Agents, 2017; Dickinson, 2015; Alonso, 2015; Bourriaud, 2014). Artists since the 1970s that have been engaging audiences for climate change, restoration of ecosystems and protection of watersheds using models for sustainable restoration are Newton & Helen Mayer Harrison, AMD&ART/ T., Allan Comp, Jean Paul Ganem, Tim Collins & Reiko Goto, Yolanda Gutiérrez, Patricia Johanson, Lynne Hull, Ichi Ikeda, and Aviva Rahmani.

To bring some of the most recent examples of events created to engage audiences for environmental issues in the framework of Anthropocene are:

1) ’The Great Acceleration: Art in the Anthropocene’ at Taipei Biennale (2014) with the participation of 52 artists (http://www.taipeibiennial.org:8080/index.php/en/). As Bourriaud described (2014), the exhibition addressed the cross-overs appearing in the art of the Anthropocene; it was focused on artists for whom objects, products, computers, screens, chemistry, natural elements or living organisms are interconnected with humans, and can be used by them for a critical analysis of contemporary world. The exhibition highlighted the way artists focus on links, chaining, connections and mutations: how they envision planet earth as a huge network, where new states of matter and new forms of relations appear (Dickinson, 2015; Lin, 2015).

2) ‘7 MIL MILLONES’ (http://www.eacc.es/7-000-000-000/info/) referred to the total human population inhabiting Earth and was hosted at EACC in Valencia, Spain (Alonso, 2015).

3) ‘Dark Ecology project’ (2014, 2015, 2016) inspired by Timothy Morton’s concept of ‘Dark Ecology’ and his philosophy of ‘Ecology without Nature’. Morton offers a radical criticism of the modernist way of thinking about nature as something outside of us and instead proposes an interconnected “mesh” of all living and non-living objects (http://www.darkecology.net/about).

References

Alonso, C. (2015). Artistic practices, discursive contexts and environmental humanities in the Age of the Anthropocene. Artnodes 15, I ISSN 1695-5951.

Bourriaud, N. (2014). The great acceleration. Art in the Anthropocene. http://www.taipeibiennial.org:8080/index.php/en/tb2014?phpMyAdmin=ef6946252cea3105a72033fb2f279321. (accessed 18-04-2017).

Bower, S. (2010). A Profusion of Terms. Greenmuseum.org. URL: http://greenmuseum.org/generic_content.php?ct_id=306. (accessed 06-04-2017).

Dickinson, B. (2015). Pleistocene, Holocene, Anthropocene. Features 02, ART MONTHLY, Sep 15, 389 pg.

Dark Ecology Project. (2014, 2015, 2016). http://www.darkecology.net/about. (accessed 04-18-2017).

Flantua, S.G.A., Hooghiemstra, H., Van Boxel, J.H., Cabrera, M., González-Carranza, Z., González-Arango, C., 2014. Connectivity dynamics since the Last Glacial Maximum in the northern Andes; a pollen-driven framework to assess potential migration. In: Stevens, W.D., Montiel, O.M., Raven, P.H. (Eds.), Paleobotany and Biogeography: A Festschrift for Alan Graham in His 80th Year. Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis, pp. 98–123.

Flantua, S.G.A. & Hooghiemstra, H. (2017) Historical connectivity and mountain biodiversity. In: Hoorn, C., Perrigo, A., Antonelli, A. (eds). Mountains, Climate and Biodiversity. Wiley, Oxford, UK.

Francoeur, E. (1997). The Forgotten Tool: The Design and Use of Molecular Models. Social Studies of Science. 27(1), 7-40.

Groot M.H.M. (2012). ‘’Solving a Piece of the puzzle’’. Reconstruction of millennial-scale environmental and climatic change in the northern Andes during the last glacial cycle: An integration of biotic and abiotic proxy-information. Ph.D. Thesis. University of Amsterdam.

Knebusch, J. (2004). Planet Earth in Contemporary Electronic Artworks. Leonardo 37 (1), 18-24. URL: http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/len/summary/v037/37.1knebusch.html (accessed 06-04-2017).

Lin, A. (2015). Taipei Biennial: The Great Acceleration. Art Review Issue. Taipei Fine Arts Museum. Jan & Feb 2015. URL: https://artreview.com/reviews/jan_feb_2015_review_taipei_biennial/ (accessed 06-04-2017).

Muller R. A. & MacDonald G. (1997). Glacial Cycles and Astronomical Forcing. Science 277 (5323): 215–8.

Symposium Agents in the Anthropocene: Trans/disciplinary practices in art and design education today. (2017).Piet Zwart Institute / Willem de Kooning Academy, Rotterdam. January 27-28, 2017. https://www.anthropoceneagents.nl (accessed 04-18-2017).

The Greenmuseum (2010). URL: http://www.greenmuseum.org/. (accessed 06-04-2017).

Torres, V., Vandenberghe, J., Hooghiemstra, H. (2005). An environmental reconstruction of the sediment infill of the Bogotá basin (Colombia) during the last 3 million years from abiotic and biotic proxies. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 226, 127–148. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2005.05.005

Torres, V., Hooghiemstra, H., Lourens, L., Tzedakis, P.C. (2013). Astronomical tuning of long pollen records reveals the dynamic history of montane biomes and lake levels in the tropical high Andes during the Quaternary. Quaternary Science Reviews 63, 59–72. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2012.11.004.

Van der Hammen, T. (1974) The Pleistocene changes of vegetation and climate in tropical South America. Journal of Biogeography 1, 3-26.