User:Δεριζαματζορπρομπλεμιναυστραλια/thesis1

abstract

The web is the world of classified information. Individuals operate within databases and their lists in order to access information and gain understanding and meaning of the world. The research explores the effect of the list on the online information collector by looking at the political and ideological dimensions of classification systems. Later on focuses on online lists of search results, their aesthetics and why I believe they enforce a flat online experience.

INTRODUCTION: THE LIST

We are online information collectors. Looking for information inside the web, we operate in fixed structures, databases and their lists. Lists nowadays function as, or are part of, search interfaces to online information and the online information collector is constantly confronted with them.

I am interested in the list as a construction of culture that affects the act of (information) collecting and enforces order. This order could be numerical, chronological, alphabetical, even random. Still I see order as an ideological construct, an outcome of ideologies of effectiveness and productivity within a certain economical system based on knowledge. To me it brings somehow something wrong in the way it makes us see and construct our selves and the world. There is a political dimension in the list. Looking at the model of the list in online space and particularly spaces of information collecting, like online archives or search engines of the web, I see it as an expression of a flat online experience. Online man collects within collections. Their lists are visually same, and look bureaucratic, therefore they reduce a possible interesting online experience to a very flat one.

I see the list as a form that manages free/empty space with thin lines and box shaped subforms, with the scope to control and bring a specific order to the listed names of things, and the ideas/concepts they represent. As an empty form,it seems that anything can happen within it. However, the names of items listed have to share a minimum similarity, otherwise this is not a list. Therefore the relationships among them become fixed and the space among the concepts that they represent is also becoming fixed. The items are assigned a significance as a whole, they become a concrete knowledge entity.

The popular search interfaces we use online and their lists of results are extremely predetermined, they destroy the sense of play and of the hunting of information, they even destroy the sense of space. The results of a search could be displayed in a much more playful way that would emphasize collecting of information online not as picking items from a list but more as exploring a world of possibilities.(here maybe examle of an alternative interface by Galloway?)

The list is the expression of template choice. If one is asked to pick some items from a list, he is asked to select from an already curated group of possibilities. Additionally, we often operate within the limitation of the incomplete list and this makes it even more problematic.

In my personal practice I have been dealing with lists either in libraries I was working in or as an artist working in the online environment. Working with online databases and recontextualising classified objects towards the design of a subjective online space. Through my online practise I realize that I am confronted with the apparatus of the list almost in every aspect of the online experience. While I have been using the Sketchup Warehouse library to collect items in order to be assemled to compose new spaces, I have been realising also how complex and chaotic the sketchup database is. Its list attempts to bring some order which sometimes seems to me utopic and impossible. The following screenshot presents a search for a “3d human” I conducted which led to results like cars or dogs and not only humans. It seems to me that the list is bringing an epiphasis of objective order, particularly after the emergence of folksonomy, the practise of social tagging on content by users, where ammounts of subjectivity have entered the cataloguing practise often times outside of controled vocabularies.

I want to explore what is the effect of the list on the online information collector.

It seems useful to approach the politics and ideologies behind classification, and the aesthetics of the list that reflect them to explore such an issue. Alltough lists and classification systems are widesrpead everywhere in the whole of our lives, at least in library science, we overlooked slighlty the political dimensions of classification, and I think that we totally overlooked the aesthetics of it.

Exploring the list effect on the user of the internet is important to extract insights that would be taken into account in the design of different search interfaces, and their possibilities of providing a different online experience as a response to the established one.

THE COLLECTOR AND THE INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY

Humans have been always bound with the act of collecting. James Gleick (2011) wrote the book Information : a theory, a history, a flood, a study on humans understanding on information.In the beginning of the book the author quotes Marshall McLuhan: ”the food-gatherer reappears incongruously as information-gatherer” (p.9).

This is an important observation that highlights that the act collecting is present in human society from the level of collecting food for survival in the prehistoric period but exists still in our societies in another mode. It also emphasizes information as a vital element of our survival. The act of collecting food transformed throughout societies into collecting goods, tools, artifacts. Its contemporary mode is this of collecting online information, activity significant for our survival, in a world where knowledge and information bring power.

If we agree with Gleick that humans are naturally collectors, the technology of the list seems a meaningful and very useful tool. On the one hand supports memory, provides easy and time wise effective access to information. But on the other hand we should look at it as all technologies and media. It shapes us and constructs us in a certain way. It brings a specific way to look at things and as i will argue, promotes the culture of template choice ,while particularly in the online context brings also a flat online experience. Flat here should be understood as boring but also as an experience with no sense of space. While online space offers many possibilities to create dynamic and interesting information spaces, the lists through we access databases , so the way our search results are presented to us , doesnt seem to invest in these possibilities.

Throughout the book Gleick emphasizes also the construction of information tehnologies and how they transform the way human perceive information. He sees the aplhabet as the major information technology that dominates our culture, and by doing so he introduces a topic that will be explored later in the reseach, the issue of literacy within written cultures. He highlights connections between the list and the alphabet by saying that “..alphabetical lists were mechanical, effective, and automatic”, while he compares them to what he calls “topical lists”, that different cultures created before the alphabet and were local classifications which he charakterised “creative” and “imperfekt” (p.63).

The list is an information technology and one of the first constructs that emerge following the technology of writing. Some of the first writtings of humanity were in fact catalogues.

Writting is an ancient technology. Calligrapher and scriber Donald Jackson(1980) in his documentary “ Alphabet: the history of writting” explains how writting has been transformed throughout its history. In its various stages it has been using symbols like icons, numbers and in the end letters. The form we still use today, the alphabet, is a much newer construction that follows the evolution of writting, alongside with the evolution of tools of writting like the pen and materials, from the stone to papyrus and the paper. The intercultural evolution of writing included a gradual reduce of the symbols used and the simplification of the whole system. For example as Jackson presents, in Mesopotamia the writting system indluced 2000 different symbols. Cultures took into account the need for simplification in order to allow language to spread throughout society. But it was only the second half of the seventeenth century when the alphabet became an “arbitrary” system, according to Michel Foucault(1966). As he writes in the Order of things, the technology of the alphabet “reconstitute[d] the very order of the universe by the way in which words are linked together and arranged in space”.(p.42)

This function seems very similar to the function of the list, the linking and spatial arrangment of the names of concepts.

PROBLEMATICS OF CLASSIFICATION SYSTEMS

I will explore the notion of classification through the lense of library cultures, as they are my practical field of knowledge and additionally because I see them as pre-web cultures, in the way they deal with the organisation of information.

Library Scientist Maria Kazazi (1994) in her book Classification Principles writes about the classification and its goals. According to her, classification is a form of hierarchy between human environment and human mind (p.). It is a key to knowledge. It is all about dividing a total in classes. It is a system of classes and their relationships. She also explains that classification is abstract. It gives a general view of the world (p.).

The goals of classification could be summarized as following: to defeat chaos (p.), to require from the user the minimum effort to search the collections of the library and to support memory. We can see then the list as a sort of material outcome of classification and as a structure that supports its purposes.

On the one hand, it is impossible to imagine the world without lists and without classification. There are great reasons for creating lists and there is a great functionality within them which makes life easier.

There are also philosophical origins in the construction of the list. Umberto Eco (2009) in his Infinity of the list essay, (p.) claims that we do lists in order to comprehend the unknown and to defeat death .We list in order to create meaning of ourselves and the world around us, which can be both seen as Eco’s “unknown”. “We like lists because we dont want to die” he writes (p.). Defeating death brings us back to the idea of survival and collecting that was stated previously, but if we consider that even for ancient cultures to defeat death was to achieve immortality through memory, also highlights the value of memory, which is beeing supported through information technologies.

On the other hand, the list, as bound with the concept of classification , carries the later's problematics and challenges. Kazazi explains also some crucial problems of classification: First of all, knowledge gets outdated. Additionally, classification systems reflect older values. Furthermore, we do not classify the objects themselves, but the concepts (p.). And not even the concepts themselves can be listed, but their material existence, their name, the word.

Another issue of classification is the idea of classes of similarity and not of difference lets say. The exlusion of diference and the abstraction of grouping things. And the normalization of this grouping. Classification affects the relationship between concepts / objects, which can be hierarchical, syntactic or semantic.

Classification is so useful and so required, to an extend that we cant imagine surviving without it. It though seems that its problematics which talk about normalization, representation, abstraction, language and knowledge have a very political and ideological dimension which will be further explored in the following chapter. As the concept of classification is so relevant to the online world, a world which is precisely classified information, it is interesting to see how the problematics of classification are embedded in the database criticism of Mark Poster (1990) in his work The mode of information, and Evgeny Morozov (2012) with Net Delusion.While Poster extends Foucault’s ideas of the panopticon and surveillance to the database which enforces participatory surveillance and normalisation, Morozov sees the database profiling of people as creating an abstract and normalised representation of them.

POLITICS OF CLASSIFICATION

There is a critical issue with classification related to power and control: who is exercising classification. This issue is actually not one sided: who is doing the classification is the second part of the question. Who created the classification system is the starting point.

In the world of libraries and archives, at least in western culture, two main systems of library classification have been used and adopted by the majority of libraries or similar institutions. The most popular classification system is DDC, Dewey Decimal Classification. It was invented by the american librarian, educator, entrepreneur, Melvin Dewey in 1876. Next would come the UDC, Universal Decimal Classification of belgian information scientist and documentation scientist, activist and entrepreneur Paul Otlet, published around 1907. Both Dewey and Otlet were born at the last decades of the 19th century and died almost in the middle of the 20th. The first was American, the latter Belgian. They sort of represent USA and Europe as the local fathers of information organisation.

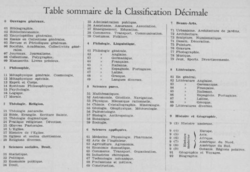

The two systems rely on a fixed structure of the first basic categories, which are divided in more subcategories each. Within this structure items should be classified and described through numerical systems which indicate their category and their specific place within it. UDC emphasizes though more on semantic interconnections of objects, through a different numerical system that uses symbols like + from algebra to indicate two different fields that they item can be assigned in. The image shows the basic design of UDC:

The main library classification systems of the western world have been developed very closed the one to another , at the end of 19 and the beginning of the 20th century. Here Kazazi's observation that classification systems reflect older values becomes easy to recognise. First of all, these systems are very old. Moreover, they, and particularly DDC, rely on Aristotelian views on classification. the idea of categories as classes, the approach of general to narrow and grouping based on similarity. Categories are classes, disctint, huge, stable entities. And every (new) concept fits into them as a narrower term, therefore adopting new knowledge means always to go even narrower within existing categories. UDC expresses a different model though: semantic links are present in the design of this system. Its important here to notice that DDC is much more widely used than UDC.

Aristoteles, as a “father of classification”, brought of course the concept of Logic behind these classification approach. In his History of Animals he is the first to attempt to classify all the kinds of animals. His core concept, grouping things according to their similarity, was a major contribution in the development of taxonomies and science, and it is still a very strong charakteristic of them. However, as Gleick points out, our categories and classification systems are adressing the literate people of the written culture. The author draws on Al. Romanovich Luria ‘s research on illiterate people in remote Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan, that do not recognize the categories of the written cultures, and accept rather geometrical shapes. The major finding of his research was that oral culture people dindt “acceptt of know logical correlations” (p.40.). Therefore this idea of logic behind categorical work should be understood mainly as the idea of logic of western written cultures.

UDC and DDC have been designed through personal efforts and views of these individuals that were envisioning organisational systems. Both Otlet and Dewey have been very passionate and visionary in their field. But on what kind of ideological background did they operate?

They both have been very early interested in the world of complex information, and its organisation, and have been dealing with information science even before its formation as a science related with cybernetics, control and communication. Particularly Paul Otlet is considered to by “the father of information science” as the wikipedia entry about him states.

They were both also involved in business, in fact they have been both selling their catalogue cards and systems. They both had standardization and globalization visions.

However, they had mainly social visions, that would be imagining organisational systems of information that would promote communication, knowledge and peace.They seem that recognised that the world would become a complexity of information territory and the power will come together with knowledge.

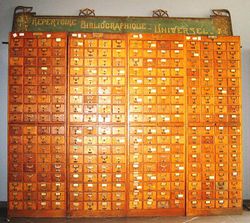

Particularly Paul Otlet was talking about a "collective book" a "universal book of knowledge". He created the Office International de Bibliography in 1895 together with Henri La Fontaine, in order to design a universal library – The Mundaneum, an institution that would gather all the knowledge of the world , which was later partially destoryed by the Nazis in the 2nd world war. In the following photograph we can some of the drawers of Mundaneum that contained the index cards.

Otlet became an important figure in Unesco. Otlet was convinced that the global spreading of knowledge and the exchange of it would promote world peace. as R.Boyd Rayward(1991) writes about in this reflektive biography of Otlet. He was dreaming of a world where the transmission of information would overcome geographic boundaries.

Dewey was dreaming of a "free library for every soul". He particularly talked about free schools and free libraries and the significane of what we would call today free access to information. As described in his biography in the website of the Online Computer Library Center (OCLC) , he helped to establish the American Library association. In 1877 , while working as the librarian of Columbia College he founded there the first library scool of the world. He also initiated proigramms for traveling libraries.

Dewey emphasized mainly the idea of open and free access and he was very influential in the american library world.

The work of both influenced the wider world of library cultures but particularly their views on connected and free information can reflekt todays world and possibly are more relevant to our experience than they were to the societies the lived in. Their ideologies contained the understanding of the power of information and data together with the understanding of their social significance.

Another important figure of the same period, philosopher, sociologist and political economist Otto Neurath, seems to understand the importancy of pictorial language, in a similar manner. Where Otlet and Dewey created a vision of a proto-database, a srtucture that would hold together universally big ammount of information, Neurath proposed methods of information visualisation. Together with ilustrator Gernt Arnzt and his future wife Reidemester they designed the project Isotype. The International System Of TYpografic Picture Education contained 4000 symbols designed by Arntz, that represented key concepts of the fields of industry, politics, demographics and economy, as explained in Arnzt web archive. Otto Neurath focuses on “uneducated persons and to facilitate their understanding of complex data” as Frank Hartmann writes. (2008, p.279) . In other words Neurath and his colleagues were dreaming of a universal system of information exchange, like Otlet and Dewey, only that Neurath was taking a distance from linguistic normes, recognising that illiterate people were by default excluded by powerfull knowledge.

All these ideas should be taken into account when we attempt to desrcie the ideology behind classification systems of our times. The need of a universal language is always present as it seems within the ideas of organisation visionaries. Their work shared the need for social change and a man who understands his world more and more. However, nowadays we can look at these people not only as visionaries but also as utopians. They views and dreams are translated through the lense of corporate knowledge capitalism, and effective production. Corporations are the knowledge institutions of our days. Google’s classification is much more present in our life than the classification of a library. Otlet’s ideas about semantically connectec gathered information and universal books of knowledge leading to a world peace are challenged by the corporate and state power on information.The ideas of freedom of access of Dewey are quite challenged within corporate practises when online content is still bound on corporate servers.

On the other end, within library worlds, the cataloguers are the librarians. Each essential part of the cataloguers job to work then with the adopted classification system of the library, so to say with the list of categories of this system. Additionally one works also with the so called controlled vocabularies, a thesaurus of terms. As critical librarian Emily Drabinsky (2012) writes in Teaching the radical catalogue: "Every object in a library will be placed in a subject division and assigned controlled terms, nothing lies outside of the system" (p.199). The author looks at library classifications as “totallising projects” while adresses the issue of the language used in classifications as a reflection of “social structures” (p.199) related to power and control. She makes her point clear when she brings an example from the Library of Congress Classification system, where as she explains there is not a conrolled term for conflicts related to “Israeli occupation of Palestinian territories” (p.199-200). Information for potentialy interested would be find under a “general heading for ARab isreallei conflikts.” and as she claims this “denies the specificity of israelli attacks on palestinian”. She continues with the fact that “ISRAELI-ARAB CONFLICT is listed as a cross-reference for ARAB-ISRAELI CONFLICTS, which she claims means that LC considers the Arabs as responsible and “originators” of the conflicts (p.200).

These systems, particularly the LOC and DDC which are the most popular in use, have been further developed and attempts are systematically made to update them. OCLC, a research center for libraries, maintains for example a web-dewey version. Moreover, updates in knowledge fields are being also adopted. As some dictionaries oftentimes publish new terms , words or concepts, so do classification tables and thesauri used by libraries get updated. But of course this process is institutionalized and takes time. And every new entity has to get standardized before put in use.

It seems that there is a collaboration of two factors then, important for the cataloguing practice. What kind of classification system the library is using, and what is the cultural capital of the cataloguer, which possibly makes him or her do specific choices in where a book should be classified and what keywords are going to be assigned to it. An interesting tension can emerge from this question: is there a certain degree of "freedom of choice" for the cataloguer? According to Drabinsky, as stated above, no. Nothing lies outside of the system as she says. Categories and controlled vocabularies represent fixed values. Therefore, seems more relevant than to examine each cataloguers ideology or culture , to understand that he is operating under a template choice standard. To explore what the cataloguer is carrying in terms of ideology , is to explore what template choice means.

A significant research that explores the political, ethical, social implications of classification is the one of Geoffrey C. Bowker and Susan Leigh Star (1991) in their critical study Sorting things out: classification and its consequences. In this book they explain that "all classifications, including those in libraries, function according to a set of three ideals [first of all ] they apply a system of classificatory principles to a given set of objects…" (quoted in Drabinsky, p.199). The authors understand classifications as systems that demand certain principles to be applied. They state that they are different than standards, but they are to be standardized, while “a standard [..] is a way to classify the world”. (p.12). To me the template choice is precisely this form of choice upon a given set of principles. As cllassifications become standardised, choices become also. Models of how to work, to communicate and to think. And these standards are applied to a trully variably and heterogenous mix of objects. Classification systems are meant to be able to conceptually fix any given set of objects in a certain manner.

When standardized, classification systems can also can become global, as happened with DDC and UDC for example. Here another issue emerges, the possible conflicts between standardized and local classification systems, as brought up by Bowker and L.Star (p. 326) and explored above thourgh Drabinsky’s example. Bower and Star think that local classifications are pushed away by the standardized ones, notion that allignes also with Gleick’s idea on “topical lists” and their replacement by “alphabetical lists”.

Furthermore, for Bowker and L. Star, classification systems are part of modern Western bureaucracy. “Assigning things, people, or their actions to categories” is a ubiquous part of work in the bureaucratic state”. (p. 285). Alison Adam’s (2008) view alligns with this notion, when in her essay "Lists" quotes Bruno Latour: "the main job of the bureaucrat is to construct lists that can then be shuffled around and compared" (p.175). The dependance of bureaucracy on lists is of course obvious. One has in mind an employe in a public service. His desk is full of paper. Lists and lists of lists. He is always trying to navigate within the state (of) classifications. Citizens as users of bureaucratic systems do also always have to fill forms and compile lists of various kinds of information.

Bureaucracy acquired a new dimension in information, service based societies. We live in the society of not only a state burreucracy but also a big companies burreucracy.Databases and catalogues of goods, services, people, are organized in an attempt to offer a great productive result. Moreover, in the online context, people have become data indexers as Manovich(1999) states in his article “Database and symbolic form” (p.7). Users not only search and access but they classify and archive in a variety of media and this consists in a great amount their online experience. They do it for themselves, by organising personal material and found information, they do it for the companies, by listing metadata and experiences in order to construct online profiles in a burreocratic and standardised way that operated in favour of the company and the advertiser it adresses.

Burreaucraacy is a system that relies in writting and information technologies of storing and classifying information, relies on citizens that aquire certain literacy skills. With its endless lists and form filling, needs alphabetically literate people that are able to be a part of its system.

We can also think of the technology of writing as a medium of the distribution and realization of standardization. It is the materiality of the medium that makes this ideology circulate and get applied. It can be revisited, even revised, it can be translated and of course stored, therefore reproduced.

Therefore it enforces the culture of the template choice, where standard options can be stored and then exist as a predetermined range of possibilities.

If then classification systems and lists can be used by alphabetically literate people. The list becomes a device for the literate. Moreover ,the alphabet seems then as an extension of the list. A catalogue with 24 units of the mimimun possible meaning to be composed in a new one every time. The alphabetical technology then itself seams to be suffering from the template choice idea which challenges the openess of the alphabet in possibilities of meaning.

THE LIST AS TECHNOLOGY OF THE SELF

It seems that not only libraries, but also we as individuals mainly adopt classification systems than create. Media theorist Stuart Hall (1997), in his “Media and representation” lectures, explained that: "the capacity to classify is a genetic feature of all human beings." Humans not only share collecting nature but also classifatory nature. Collecting is bound with beeing able to classify what you collect, to access it again, to remember what it is and where. Additionally, as bigger ones collection expands, classificatory needs start show up.

On the other hand, following Halls arguement,"the particular classification system used in a society is learnt". To Hall, without any notion of classification we cannot comprehend the shared conceptual maps of our culture. “To become a human subject is precisely to learn or internalize the shared maps of meaning with other people in your culture" he states in his talk and this is not necessary something we learn within formal knowledge processes. Moreover he specifies that it is about becoming a "cultural subject" rather than a biological one.

As he highlights then, lists and classifications are constructions of culture which if we do not appropriate and reproduce we cannot at least culturally become. But if they are learnt within a cultural or social context, then we can approach them as means of training.

Hall's approach in what is to become a human subject is maybe indicating that we need to understand the shared meanings of our culture in order to be productive and creative, in other words socially useful. This notion comes close to the ideas of Michel Foucault about biopolitical govermentality as presented in the publication edited by Michel Senellart “Michel Foucault: the birth of biopolitics”(2008).

The idea of a state which produces a normalized subject has been related by Foucault with the first bourgeois societies.He thinks that the notion of a state caring about the individuals formation was not keen in sovereign societies. In the bourgeois societies and on, the concept of govermentality he introduced becomes biopolitical. In that sense the art of governing is directed towards governing also the individual in order to produce him or her in a suitable manner suitable to the exercise of power and control and their reproduction.

Govermentalities are based in sets of practices. The technologies of production, sign systems, power and control and technologies of the self are each a “matrix of practical reason”. (Gutman et, p.18) These technologies that hardly work independently.I am mainly focusing here, related to classification systems and lists, in the technologies of the self . It is interesting to note though that the technologies of power are, always according to the author, working towards an "objectivation of the subject” , while the technologies of the self "permit individuals to effect … a certain number of operations on their own bodies… and to transform themselves in order to attain a certain state of happiness, purity, wisdom, perfection or immortality" (p.18) . Both technologies compile the concept of govermentality. As he explains in his lectures The culture of the self, each technology brings certain modes of training of individuals, and are not just about gaining specific skills but also certain attitudes as he calls them. Moreover, as he describes, these technologies have been filtered and transformed by mass media, to illustrate that the culture of the self is not an independent culture.

In his History of Sexuality, Foucault explains that western man was "gradually learning what is to be a living species in a living world, to have a body, conditions of existence".(p.142). Classification systems can be seen as this means of training through which an individual, part of a wider culture, can learn what is to be under particular existential conditions of categorical devisions.

How does the list operate as a technology of the self? First of all it gives identity. Identities (in theoretical or in the practical sense) have been always been about categorized metadata describing the individuals. The list structure of the official state identity survives and gets reproduced in the social networking context, for example in online user profiles. The list gives identity through classifying. The list, as explained previously, gives listed items a significance as a whole. This reminds the concept of imagined coherence that Isabel Llorey (2013) writes about in her essay Governmentality and self-precarisation. In this article she explores the normalisation of cultural producers through Foucault's biopolitical govermentality."The normalizing self-governing is based on an imagined coherence,uniformity and wholeness that can be traced back in the construction of the white male.." (p.59). Therefore the list not only assigns identity through classification, it assigns also to the person out of nowhere an "imagined" coherence, which is a great example of normalization. The list gives identity and normalizes.

As Eco claims, we make lists in order to defend the unknown and death, therefore we can see how practices of making and reading lists can become these operations that according to Foucault bring us in a certain state. The list attempts to transform us in a state of wisdom and immortality.

We are indeed taught of classification systems, they are part of our fundamental education and appear interdisciplinary. We are learning classification systems of biology, of language, of mathematics and so on. However we are able to respond to all this new learning experiences only after we develop certain reading and writing skills, the focus on which comes always in the very beginning of our school years. Not only reading through lists but also keeping notes that reproduce them, supports the memory of the literate. On the other hand, getting assessed through lists and the multiple choice model for example, seams to be a clear expression of the template choice culture within our formal training.

Overall, by exploring the political dimensions of classifications and the effect of lists, we can observe that they are ideological constructs, interconnected with the concepts of standardization, boundaries, bureaucracy and literacy. Moreover classification systems are means of training and normalizing, while the list materializes the problem of the template choice. All these seem very fixed conditions to become, to get formed as subjects and understand the world. As Foucault states, they are "fixed and determinate processes" of self constitution and of "knowing a determinate, objective set of things". [quoted in Kelly, p.79]

SOURCES

Michel Foucault. The order of things. 1966

Donald Jackson. Alphabet: the history of writting. 1980. [ accessible at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7IUBglyvt8o]

Michel Foucault. History of sexuality: vol3, the care of the self. 1984

Gutman, Hutton, Martin (ed.). Technologies of the self: a seminar with M. Foucault. 1988

Mark Poster. The mode of information. 1990

W. Boyd Rayward. The case of Paul Otlet: pioneer in information science, internationalist, visionary: reflections on a biography. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science. 23(1991):135-145.

Geoffrey Bowker and Susan Leigh Star. Sorting things out:Classification and its consequences.1991

Maria Kazazi. Arhes taxinomisis[in greek]. 1994

Stuart Hall. Representation and the media. 1997.[ accessible at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6sbYyw1mPdQ]

Lev Manovich. Database as symbolic form. 1999

Alison Adams. Lists. in Software studies: a lexicon. 2008

Frank Hartmann, Visualizing Social Facts: Otto Neurath’s ISOTYPE Project, in European Modernism and the Information Society edited by W. Boyd Rayward, Ashgate, 2008, pp.279-29

Michel Senellart(ed.). Michel Foucault: The birth of biopolitics : lectures at the College de France, 1978-79.2008

Umberto Eco. The infinity of lists. 2009

Mark G. E. Kelly.The Political Philosophy of Michel Foucault. 2009

James Gleick. The information: a history, a theory, a flood. 2011

Evgeney Morozov. Net delusion. 2012

Emily Drabinsky. Teaching the radical catalogue. In Radical Cataloging: Essays at the Front, 198-205. 2012

Isabell Llorey. Govermentality and self precarization: on the normalisation of cultural producers. Translated by Lisa Rosenblatt and Dagmar Fink. in To the reader/BAK.2013

How one library pioneer profoundly influenced modern librarianship. OCLC, [accesible at https://www.oclc.org/dewey/resources/biography.en.html]

Gerd Arntz webarchive. [accesible at http://www.gerdarntz.org/]