User:Lbattich/Essay on method - (final version): Difference between revisions

| Line 57: | Line 57: | ||

The practices of what is now called conceptual writing have influenced my artistic development since 2011, although I arrived to these issues not from practitioners such as Kenneth Goldsmith, but rather from considering the history of conceptual art, and particularly the instruction-based works of Yoko Ono, and the language works of Joseph Kosuth, John Baldessari and others, as well as the Oulipo literary movement. | The practices of what is now called conceptual writing have influenced my artistic development since 2011, although I arrived to these issues not from practitioners such as Kenneth Goldsmith, but rather from considering the history of conceptual art, and particularly the instruction-based works of Yoko Ono, and the language works of Joseph Kosuth, John Baldessari and others, as well as the Oulipo literary movement. | ||

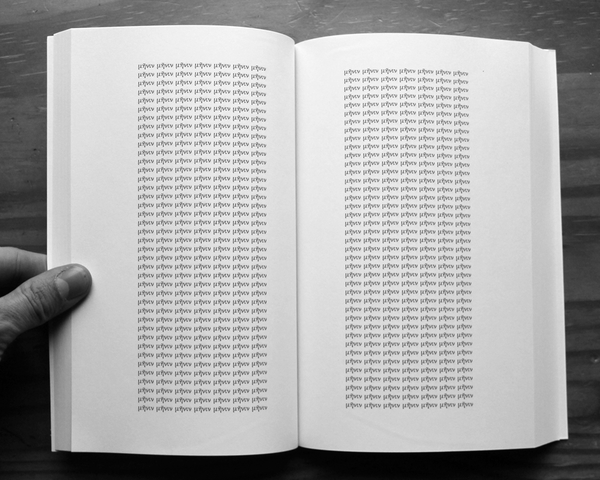

The artist book μῆνιν ( | The artist book μῆνιν (''menin'', Ancient Greek for anger, wrath) was produced in 2012 with this artistic and cultural background in mind. μῆνιν is a book where the first word of Homer’s ''Iliad'' is repeated throughout the whole length of the poem, which is originally composed of 15,693 lines. The use of the Ancient Greek word for anger/wrath is not meant to be explicitly negative or judgmental toward Homer and the canon. The work does not express this wrath, merely appropriates the word. The point for me is to linger in this word, the very first word of the whole of Western literature, by creating a systematic exposition. At the same time, I find it interesting that we know next to nothing on the author or authors of the first work in the literary tradition in Western culture, and that subsequently this culture would develop an almost obsessive cult on the individual creative originator. | ||

[[File:Menin.png|thumb|center|600px|''μῆνιν'']] | [[File:Menin.png|thumb|center|600px|''μῆνιν'']] | ||

Revision as of 09:58, 17 June 2015

"We have an immeasurable longing to become whole." -Nietzsche

Incomplete Manifesto

Any single work never stands alone. It belongs to a series.

A series is itself in essence incomplete.

A series is like a musical suite, composed of movements. Even if it is composed of one movement only, the suite contains all other possible movements in its incompleteness.

Each movement is the aspect of a totality that will never arrive, yet it is intended.

The idea of completeness is contained in each movement and each suite, but only as an idea that drives the suite.

The incomplete essence of each suite or series alludes to the idea of unattainable wholeness.

A complete movement, a complete series, are no more than mythological creatures.

A movement can belong to more than one series. New series emerge from existing movements.

A series belongs in turn to the sum of an artist’s oeuvre.

This oeuvre is never complete, though it is precariously total at any given moment.

The movement, the series, the oeuvre, are in constant

Introduction

My artistic strategy involves the production of process-led works in different artistic mediums. In broad terms, the main areas addressed through my artistic investigation are our engagement with artistic history and aesthetic experience as affected by the digital technologies we take for granted today. This interest is manifest in practices of quotation, re-appropriation and citation of past cultural works, mainly taken from the institutional canon of Western art.

This investigation includes a consideration in how canonical narratives are constructed, and the apparatus that exerts its authority for these effects. This area of interest has led me to work on authoritative art history books, the use of the proper name within the art circuit – which has the tendency of framing the artist’s identity into a contralized, unified and institutionalized subjectivity.

Brief sketch of my background and current practice

I have developed as an artist by first engaging with water-based mediums and printmaking, influenced with the Romantic tradition, and the notion of the sublime in art and nature. In more recent works this interest has been manifest in my exploration into the experience of colour.

What interests me in this theme is the tension between a purely sensatory experience, and the drive or desire to formalise and structure that experience in an schematic representation: (language, digital colour values, Pantone values, scientific schema of colour spectrum, etc.). For my approach to the nature of this tension, I have benefited from David Batchelor's Chromophobia.

As philosopher Charles Riley remarks, “Colour refuses to conform to schematic and verbal systems.” (Riley, 1995, 12) In my works on colour so far I have aimed to addresses the tensions inherent in mediated experience, where concrete sensations of colour encounter the abstract and rigid language of algorithms.

Along these lines, I've developed a series of photographs, Colour Suites, as a suite of colour studies. The imagery, with its allusions to Romanticism, shifts the approach to colour away from the divisions and coding of digital media, into more fluid and otherworldly relationships. The film Colour Étude is a study of signal corruption in digital media, where unexpected digital colour patterns are generated by chance interventions on several video files. This malfunction is later intentionally manipulated, edited and controlled.

Recently I have continued to develop prototypes for studies of colour in digital media, especially by concentrating on the RGB colour wheel, which is widely used as a standard on the web and digital displays.

In a broad sense, my work on this area aims to provide an opportunity to meditate on the artificial colour systems that dominate our experience of the world through media technologies.

Conceptual writing & appropriation

This emphasis on the impact and effect of media technologies in our experience of the world is related to my interest on strategies of appropriation in art, which has been central in both previous and recent work.

The practices of what is now called conceptual writing have influenced my artistic development since 2011, although I arrived to these issues not from practitioners such as Kenneth Goldsmith, but rather from considering the history of conceptual art, and particularly the instruction-based works of Yoko Ono, and the language works of Joseph Kosuth, John Baldessari and others, as well as the Oulipo literary movement.

The artist book μῆνιν (menin, Ancient Greek for anger, wrath) was produced in 2012 with this artistic and cultural background in mind. μῆνιν is a book where the first word of Homer’s Iliad is repeated throughout the whole length of the poem, which is originally composed of 15,693 lines. The use of the Ancient Greek word for anger/wrath is not meant to be explicitly negative or judgmental toward Homer and the canon. The work does not express this wrath, merely appropriates the word. The point for me is to linger in this word, the very first word of the whole of Western literature, by creating a systematic exposition. At the same time, I find it interesting that we know next to nothing on the author or authors of the first work in the literary tradition in Western culture, and that subsequently this culture would develop an almost obsessive cult on the individual creative originator.

These concerns have continued to inform more recent works:

Retrograde Chapbooks

In Arnold Schoenberg’s 12-tone system, retrograde refers to the operation of time-reversing the tones in a musical series, while maintaining the original pitches and rhythms on the sequence. As a literary counterpart to Schoenberg’s retrogression technique, the Retrograde Chapbooks present existing texts from the history of modernism and the avant-garde, where all sentences have been re-arranged in the inverse order. The immediate meaning and readability of each sentence is maintained, but the overall sense is displaced within the text as a whole.

Quotations in my works are like robbers by the roadside

This web-based work is inspired by internet culture production of image-macros with quotations, and specially by the practice of "troll quotes," which misattribute all 3 elements of the image (photograph, quotation and author). On each click by the user, this work generates a new quotation image-macro by random association among these 3 elements.

The title of the work is taken from a sentence by Walter Benjamin. According to Know Your Meme site: "Troll quotes are image macros that feature a quote from a popular movie or TV show and attribute the quote to a character in another popular movie or TV show. Often the background image will come from a third unrelated pop culture source. These images are created in order to annoy or troll members of all the involved fandoms who will quickly identify the obviously incorrect attribution."

My work in context: On appropriation and “uncreative” practices

“Today the canon appears less a barricade to storm than a ruin to pick through."

(Foster, 2002, 81)

Some early conceptual art practitioners felt that their art, being 'dematerialized', would escape the usual restrains of the art market. (See, for instance, Lippard, 1973) This proved misguided: conceptual artists, within a mere three to five years, were as 'marketable' as artists working on the traditional mediums of painting and sculpture. Documentation and sketches took over the place of 'dematerialized' artworks, and the aura of the artists (as brand) replaced the aura proper to the physical presence of the artwork.

Several early appropriation artists (during the early 1980s) claimed that they were challenging "ideas of competence, originality, authorship and property." (Barbara Kruger, quoted in Foster, 1996) While they certainly challenged some strands of traditional thought on those ideas, at the end this also proved misguided to a degree. They became (and always were) subsumed by the powers granted by the 'originality' they set to challenge. Notions of the original, authorship and propriety, in this case were shifted from a skill-based craft, to an intellectual-based practice, but they changed little otherwise. (For more on this reading of the Pictures Generation as asserting authorship rather than subverting it, see Crimp 1982, and Harrison, 2010)

Similarly, 'uncreative' and 'conceptual' writing during recent years, is meant to do away with traditional ideas of originality, creativity and authorship. And it is doing a great job at that. But at the same time it repeats the cynical reasoning of early appropriative art. Not surprisingly, given that 'uncreative writing' is basically a form of appropriating, less in the manner of quotations and citations, and rather in the manner of appropriative art of the Pictures Generation. It shifts long held problems in the visual arts to literature. The author is not so much the one that 'writes' the words ex nihilo, so to speak, but one that appropriates them and arranges them in different configurations following a certain plan or logic. And yet, for all that, authorship here is no diminished. As in the previous shift from objects to ideas in the artworld, this notion of authorship just makes a move from the words-as-objects to the creative authority of the author's plan or logic for the work. This fact is made evident in Kenneth Goldsmith’s Paragraphs on Conceptual Writing (2005), which appropriates and builds upon Sol LeWitt’s 1967 influential text on conceptual art. To prentend that Kenneth Goldsmith’s works – and similar works – are subverting the concept of authorship means to dangerously ignore the developments of art (and literature) during modernism, and especially in the second half of the twentieth century.

How does authorship fit into my practice:

Although I am highly interested in the concept of authorship, most of my works do not attempt to address this directly, or at least it is not my intention to subvert of challenge traditional notions of authorship – in the footsteps of the Picture Generation artists. Regarding authorship, in my work I want to draw attention to the fact that that authorship is nevertheless present even in acts of appropriation. In signing my works I do not aim to reclaim the appropriated texts and images as my own, or to question the (authorial) authority of the original material, but rather, in the manner of contemporary conceptual writing, and paraphrasing Joseph Kosuth, the source material is rearranged or transformed – however slightly – into a new text or paragraph, as Kosuth puts it, and it’s that paragraph I claim authorship of.

These issues may show that it is not entirely correct for me to easily situate my work within the discourse of appropriation art – especially if we consider appropriation art in the wake of the Picture Generation artists. Although much of my practice concentrates on this, it would be best to say that my work utilizes appropriative tropes for its own ends. And these ends vary from work to work and project to project.

My works, in their attempt to use citation and quotation – terms which I prefer to ‘appropriation’ – serve as well as homages to the source texts, images and cultural objects. In this sense, they are tinged with nostalgia. Most of my works that utilize appropriative means are not primarily designed to subvert the source objects, but to present them in a different context, or utilize their aura as content for different aims, which includes treating the material in a metaphorical sense. This use of appropriation remains in stark contrast to other historical uses associated with appropriation, especially to the notion of détournement employed by the Situationist International, which refers to the practice of reusing ‘preexisting artistic elements in a new ensemble.’ For the Situationists détournement implies a devaluation of the appropriated material.(Debord et al, 1959)

On the contemporary practices of image-making, from high art to commercial products to social media expressions, appropriation of other works is so pervasive, as facilitated (and prescribed) by digital media, that it's use cannot have the same impact nor meaning it had for the Situationists and even for artists like Barbara Kruger.

Rather than devaluation or subversion, my works attempt a recontextualisation, perhaps more in the manner of homages.

Retrograde Chapbooks, for instance, proposes a literal “going-back” movement to the power of early avant-garde manifestoes. The intention here is neither to criticise the original texts, nor to question their authorship, but rather to present a concept or desire by means of a metaphor. The resulting altered manifestoes are presented as metaphors for a nostalgic desire.

Conclusion

In using a process-based approach, my challenge is to explore how these different works relate to each other. As mentioned above, I consider that the common element in my works is a consideration on the impact and effect of media technologies in our experience of the world, and of the artistic heritage of the past (both remote and recent). This interest is not often manifest as a central research area in each and all of my works, but rather functions as an connection between different and concise projects and topics.

In my works, I aim to retain a tension between aesthetic quality and conceptual criticality. For this reason, I should emphasise that my works are not conceived as militant critique on the issues investigated (being the institutional and canonical status of certain art historical narratives, etc), a criticism that would strive to reach conclusions. Rather, my critical strategy is mostly pursued by trying to enact the very notions that my works aim to critique. My works are conceived as specific interventions to highlight tensions, complexities and dilemmas in a particular cultural issue, in the hope of engaging the audience into further dialogue.

Bibliography

Batchelor, D. (2000) Chromophobia. London: Reaktion Books.

Debord, G. et al (1959) ‘Détournement as Negation and Prelude’, in Knabb, K. (ed.) (2006) Situationist International Anthology. 2nd ed. Berkeley: Bureau of Public Secrets.

Crimp, D. (1982) 'Appropriating Appropriation', in Evans, D. (ed.) (2009) Appropriation. Documents of Contemporary Art. Cambridge: MIT Press, pp. 189-193.

Goldsmith, K. (2011) Uncreative Writing : Managing Language in The Digital Age, New York: Columbia University Press.

Goldsmith, K. (2005) ‘Sentences on Conceptual Writing’. Available: http://www.ubu.com/papers/kg_ol_goldsmith.html. Accessed 3 June 2015.

Harrison, N. (2010) 'The Pictures Generation, the Copyright Act of 1976, and the Reassertion of Authorship in Postmodernity', Art & Education. Available: http://www.artandeducation.net/paper/the-pictures-generation-the-copyright-act-of-1976-and-the-reassertion-of-authorship-in-postmodernity/. Accessed 3 June 2015.

Kosuth, J. (1991) Art After Philosophy And After: Collected Writings, 1966-1990. Edited by Gabriele Guercio and Jean-François Lyotard. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Lippard, L. R. (1973) Six Years: The Dematerialization of The Art Object From 1966 to 1972. New York: Praeger. 1973.

Foster, H. (1996) The Return of the Real. Cambridge MA: MIT Press.

Foster, H. (2002) ‘Archives of Modern Art’. October, Vol. 99, Winter. Cambridge MA: MIT Press.

Riley, C. A. (1995) Color Codes. Lebanon, New Hampshire: UPNE.