User:Eleanorg/thesis/draft1.1/fullTHESISyo: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 139: | Line 139: | ||

What is most striking about these proposals for a re-worked grammar of consent (which I will call 'consent-as-collaboration') is that consent is no longer an outcome, but must be a process in and of itself. This is not surprising when we think, for example, of the differences between democratic systems based on voting, and those based on consensus. If the aim is a decision made collectively (instead of a 'yes'/'no' vote), then the proposal to be consented to can no longer be static and self-evident; it must be modifiable. The process of proposing, discussing and modifying a proposal therefore cannot be divorced from the ultimate confirmation of agreement. So what does this collaborative process of negotiation look like? | What is most striking about these proposals for a re-worked grammar of consent (which I will call 'consent-as-collaboration') is that consent is no longer an outcome, but must be a process in and of itself. This is not surprising when we think, for example, of the differences between democratic systems based on voting, and those based on consensus. If the aim is a decision made collectively (instead of a 'yes'/'no' vote), then the proposal to be consented to can no longer be static and self-evident; it must be modifiable. The process of proposing, discussing and modifying a proposal therefore cannot be divorced from the ultimate confirmation of agreement. So what does this collaborative process of negotiation look like? | ||

==Notes: Two book covers on books about consensus== | |||

[[File:consensusResults.png]] | [[File:consensusResults.png]] | ||

<br /> | <br /> | ||

Revision as of 10:16, 14 May 2013

Abstract

London Indymedia recently shut up shop, claiming that the task today is not encouraging DIY publishing, but "curating from within the sea of content". As curation becomes central to (post-)digital publishing, those of us interested in collaborative production need to ask how these curatorial decisions are being made, and what assumptions about negotiation and agreement are encoded in collaborative software. I will look at these questions from a feminist angle, drawing specifically on feminist theories of consent, to evaluate collaborative publishing models from an ethical perspective.

The thesis draws on personal interviews with feminist activists, who are struggling to articulate new models of (sexual) consent. I look in detail at emerging proposals, which critique the slogan "yes means yes" and articulate radical models of consent as an ongoing collaboration. I then ask how these speculative models for sexual consent might apply to collaborative decision-making in publishing. Specifically, I examine how a feminist tolerance for indecision and inaction might inform curatorial and design decisions. I report from the Libre Graphics Research Unit's recent lab "Collision 1" in Brussels, discussing the Collision project as a concrete example. I will give a feminist slant to the Collision project's claim that in design, "tension is deflated through erasure, simplification and filtering", and I will propose some answers to its question, "what would be ways to articulate collisions, instead of avoiding them?".

Introduction

[Introductory sentence: the importance of consent in democratic decision-making as opposed to 'democratic' curation algorithms; importance of 'yes']

But of what does this 'yes' consist?

Some of the most nuanced and challenging theories of the 'yes' are emerging from a field of activism for which the meaning of consent is of central concern: the feminist movement against sexual violence, and its complementary campaigns for consent. Standing in opposition to a culture in which "a deal is a deal, no matter how reluctantly, grudgingly, or desperately one side accepts it" (Millar p.37), feminists stress not only that "no means no" but that a reluctant yes, silence and "maybe also means no". (hugo s; OUSU; yes means yes, rtn?)

Here the meaning of "consent", initially appearing as a straightforward alternative to the distortions of the vote, is thrown into question. What exactly is consent? How must it be communicated? Must it be an act, or can it be a state of mind? And is reluctant consent still valid? The results of consent, then, also vary depending on the question and the algorithm used. (Wertheimer)

On the other hand, the feminist movement's celebrations of consent go under the mottos "yes means yes" and "consent is sexy". (yes means yes; consent is sexy) At first glance, this simultaneous problematising and celebration of consent is a contradiction, to say the least. In investigating this apparent contradiction through conversations with people active in the field, I have discovered a rich debate in which the work of resolving these questions gives rise to more radical theories of consent, which can usefully inform other fields.

This difficult theoretical work - being done within the meetings, workshops and discussions of the feminist movement - offers valuable conceptual tools, which can be fruitfully exported to other settings in which the aim is to foster egalitarian collaboration. The sexual scenario, under the intense scrutiny of feminist questioning, throws into sharp relief the nuances involved in the process of establishing agreement. In this scenario the wording of a sentence, or the flicker of an eyelid, can mark the difference between democracy and disaster. It is not surprising, then, that it is in the high-stakes theorizing of this scenario that we find some of the most exquisitely nuanced and ethical theories of consent. Far from being inapplicable to other social scenarios, these hard-won theories are readily applied to other democratic settings in which, where they seem less pressing, the nuances of the 'yes' can be easily overlooked. (suzanne h; clare c interviews)

After exploring in detail the conceptual work on consent that is happening within the feminist movement, I will look again at the problem of group decision-making, and use feminist theories of consent to evaluate various consent-based systems. I will look, specifically, at the example of collaborative online publishing. Just like face-to-face decision-making systems, online tools mediate our encounters, and encode certain models of what 'consent' and 'consensus' are.

If the software we use to collaborate encodes certain models of consent, and if our model of consent is rendered up for grabs by feminist critique, then two questions arise. Firstly, what would a radical model of consent - one which gets beyond the problematic conservatism of "yes means yes" - look like? And secondly, is it possible to use such a model for collaborative publishing?

Alessandro Ludovico uses the term "atomization of content" to describe the current situation of online publishing. Rather than consuming whole books or newspapers (or websites), readers today deal with smaller units - individual articles, images, posts - which may be aggregated and organized in various ways. The question for publishers is no longer how to create a comprehensive range of content, but how to aggregate the 'best of' from multiple sources. (Ludovico; Being the Media)

This shift is well illustrated by the recent history of the radical news project Indymedia. Two years ago I interviewed activists during the fall-out from the difficult fork in the UK Indymedia project. A central question in the split was whether Indymedia's role should be to provide its own platform for publishing, or aggregate existing content. Those I interviewed had come to the 2011 Barncamp, a week-long activist tech retreat, to work on Be The Media - one of two projects emerging from the fork. Unlike a traditional Indymedia site, Be The Media would offer no facility to post content to the site, and would only display pre-existing feeds pulled in from elsewhere.

This shift in approach has been more recently echoed by the London Indymedia collective, who shut up shop in November (?) 2012 with the rationale that "this Indymedia project is for many reasons no longer the one which we think is tactically useful to put our energy into... in many ways Indymedia won, because it pioneerd approaches which have now become mainstream... Self publishing is the norm." They conclude that rather than encouraging people to self-publish, "we in London see the challenges of today more in terms of collectivizing the individual outputs, of curating from within the sea of content".

The immediate quetion, then, is how this curation is to be done. Commenting on the discussion in progress at Barncamp, participant Mick Fuzz said wryly to me: "I think what's interesting in terms of projects like Be The Media, which involve existing grassroots collectives sharing content, is that we're getting to grips with some of the politics of aggregation." While some onlookers wanted the new project to take an approach of "linking everybody up and making sure that everybody grows - including people you don't necessarily agree with", another from a local Indymedia collective commented that "think[ing] you should syndicate every fucking nutter in the world" was a symptom of "liberal guilt". He stressed the difference between "censorship" (of which Be The Media has been accused), and "not giving a platform to somebody's mad ranty blog". (being the media)

The 'sea of content' we now live in will only make these debates more frequent, when it comes to choosing what to include in the limited space of a given page (whether digital or paper). Is it possible to do this in a genuinely democratic way?

There are multiple ways to resolve the dilemma of what to include, and various algorithms available for sorting and prioritizing atomized content. For example, one type of algorithm we hear much of today is the 'filter bubble', a term coined by Eli Parisier to describe a model in which readers are served a personalized mix of content that reflects (and re-enforces) their own preferences. Parisier proposes a reactionary, paternalistic alternative in his project UpWorthy - a site which promotes the sharing of 'important' (check quote) content. Or there are the more democratic, populist 'most watched' models, in which the most popular content is displayed at the top of the page - creating a self-perpetuating cycle. The problem for activist curators lies, as ever, in our refusal to resort to such elitist, individualist or populist algorithms. We don't want to be coldly pragmatic, but to reach consensus on what is important. If we want the software we use for collaborative curation to encode radical models of decision-making (as opposed to populist algorithms), then we need to look closer at what is entailed in this decision-making, and what assumptions we are encoding. I will look in detail here at one aspect of a radical theory of decision-making; namely, individual consent - which makes the link between the will of the individual and the will of the group. If this consent is to be expressed (encoded) through software, and we are to design this software, then we must make certain decisions. These include what exactly we mean by 'consent'; how it is expressed; and in what way a consenting agent interacts with others.

(give more detail here about web-to-print projects and how they use voting systems?)

Too Many Quiet I Guess So's: The Feminist Critique of Consent

On a cold November night I was out in the Oxford rain, shouting "whatever we wear, wherever we go: yes means yes and no means no!". It was the annual Reclaim the Night march, resurrected in Oxford in (year?) and, sadly, looking set to continue slogging away at the same ABCs for the forseeable future. No Means No. Yes Means Yes. Consent Is Sexy.

The appalling statistics on sexual violence attest to the pressing need for a greater cultural undestanding of consent. These slogans are a vital starting-point, in a culture which still fosters the violence of playing cut & paste with women's words ("No means yes and yes means anal")(SocietyPages News). Until there is general agreement on the fact that, for example, a short skirt or shiny shoe or fetching hat is not semantically equivalent to the word "yes", we seem doomed to continue shouting in the rain.

But my voice is getting hoarse from these simplistic slogans - and I'm not the only one.

A famously crass government poster campaign should have given us pause for thought recently. Having apparently digested feminist demands, it emblazoned pub toilets across the UK with the image of an intimidating male inmate staring out from a prison cell bed, captioned by the question: "If you don't get a 'yes' before sex, who'll be your next sleeping partner?" (Home Office). Leaving aside the campaign's homophobia (and its almost unbelievable achievement of implicitly condoning (prison) rape), the telling phrase is this: "get a yes".

Get a yes. Consent as an item to be aquired; as a commodity; as a type of insurance or entrace ticket. After all: yes means yes.

A recent anthology of feminist visions for "a world without rape" uses this slogan as its title (yes means yes). Tellingly, many of the essays contained therein are at pains to debunk it. One article written for the book (though not eventually included) gets straight to the point: "the problem, of course, is that there is more than one kind of 'yes'... Too many 'yeses' are coerced; too many quiet 'okays' and 'I guess sos' are interpreted as blanket permission." (hugo s) Uncritical demands for consent-as-standard can backfire, and badly. Looking upon this muddle with a lawyer's eye, Alan Wertheimer ('Ethics of Consent' p. 195) summarizes:

"[To say that sex should be consensual] raises more questions than it resolves. ...Firstly, in what does consent fundamentally consist? Is consent... a state of mind or is it an action? ....If an act of consent is necessary, is it sufficient? ...[W]hen does someone's 'token' of consent... render it permissable for the other party to proceed?"

'Consent', then, far from being a straightforward democratic model, is a complex and thorny terrain. How we define and demand it are urgent questions with far-reaching political implications. Behind the black-and-white slogans, it is the recognition of this painful truth that is making the feminist movement today one of the more interesting discursive spaces in which to explore the meaning of consent, collaboration, and thus democratic decision-making more generally. There is a growing body of feminist writing and practice which problematises the formula "yes means yes and no means no", and in so doing, articulates important challenges to any simplisitc championing of 'collaborative', 'participatory' or 'consensus' processes. By extension, this body of theory gives us tools to evaluate how consent is encoded in formal systems, including in collaborative software.

The Nature of consent

In order to lay out the terms of the debates surrounding consent, I'll use a framework outlined by the legal philosopher John Kleinig (2010) in his essay "The Nature of Consent". According to Kleinig, consent has (among others) the following three components: an ontology (what it is), a signification (how it is tokened), and a grammar (who is involved, and how they interact).

How the ontology, signification and grammar of consent are defined are political questions. These three terms give us starting-points for getting to grips with the various political positions available. (Footnote: I will take it as a given here that 'consent' is informed and voluntary; what interests me in this essay are the grey areas lying even well within the borders of legally and morally valid consent. Point to Wertheimer's discussion of legal/moral consent & coercion.)

Firstly, what is the ontology of consent? "Does it consist primarily in a state of mind... Or is it constituted by a peformative act or the conventional signification of agreement...?" (Kleinig pp. 9-10) The answer to this question splits clearly along political lines. The feminist movement unambiguously endorses the "performative act" theory ('no means no') over the "state of mind" theory ('she wanted it') (Rape Crisis Scotland; RTN; Suzanne Holsomback). Wertheimer summarizes, "a woman's secret desires have little bearing on whether [another's] action is permissable." (Consent to Sexual Relations, p.149) According to this view, it is possible to want or desire something without consenting to it (Kleinig; footnote Wertheimer distinction between want & desire). And importantly, by distinguishing between consent and desire, this theory also carries the disconcerting implication that it is possible to consent to something without wanting or desiring it. 'Yes' means 'yes I will'; it does not necessarily mean 'yes I want to'. This poses a problem for any campaign based on consent.

Secondly, how is consent signified? This is perhaps the most familiar of the popular debates surrounding consent. What, if anything, apart from 'yes' can signify consent? When we hear that a woman wearing a short skirt is "asking for it", an argument is being made about signification. Feminists are again fairly unified in rejecting this stance (see 'Not Ever', Rape Crisis Scotland), delimiting certain acceptable signifiers ('saying yes'), and rejecting others (short skirts, being drunk, flirting - see Oxford RTN 2011). There is still uncertainty within the feminist movement, however, about the finer points: must explicit verbal consent be given for each and every action? How often must it be sought and reiterated? Etc. (See critiques of the Antioch college policy in Wetheimer & Yes Means Yes). Various solutions have been offered for this question (give examples from Cochrane - 'short cicuiting' & Holsomback 'grey areas').

Thirdly, what is the grammer of consent? Kleinig (2010) proposes the following grammar: "A consented (to B) to P" (p.5). There are always three parties involved: B, who seeks some kind of permission; A, the agent whose consent is sought; and P, the act for which permission is sought. P is "a course of action... for whose pursuit A's authorization, permission, or agreement is required... which B has no right to expect of A absent A's consent" (p.7). Kleinig notes here that consent is a reactive gesture; to initiate a course of action (for example, to make a sexual advance) is different from consenting to it.

This seems fairly straightforward - and indeed Kleinig introduces it as uncontroversial groundwork in his essay. However, the grammar of consent is perhaps the most politically charged aspect of a working definition. Kleinig's favoured grammar is heavily loaded with gendered assumptions: an active (male) subject seeks the consent of a reactive (female) other. Millar & Wertheimer (2010, 'preface to a theory' in Ethics of Consent p.79) paint an unwittingly gendered picture when they summarize that consent works a "moral magic" that "make[s] it permissable for A to act with respect to B in a way that would be impermissable absent B's consent." Kleinig uses the still more telling metaphor that this type of consent "functions like a... gate that opens to allow another's access". The metaphor of the "gate" or "moral magic" is telling: the proposed act is understood as static and self-evident - indeed, the image conjured in these descriptions is of an act that will go ahead whether or not consent materialises. The only transformation it might undergo is in its ethical status; a blessing bestowed by (female) consent. It is from this grammar that the bluntly instrumentalist imperative to "get a yes" originates.

For these reasons, many feminists today are drawing attention to the poverty of "mere legally valid consent" (Kramer-Bussel, 2008). In feminsit spaces, the word 'cosent' is increasingly prefixed with various qualifiers: "healthful consent" (Holsomback 2013); "enthusiastic consent" (OUSU workshop materials?); "meaningful consent"; "affirmative participation" (Thomas Millar p.40); (get example from consenst is sexy campaign.)

These prefixes attempt to get around the awkward problem described above: that consent on its own does not preclude coercion, hierarchy or the absence of desire. Some feminists therefore demand enthusiasm /over and above/ consent. (Clare C.) Others attempt to re-define the term 'consent' itself, so that enthusiasm and active participation are part of a working definition (Holsomback).

At this point I will generalize that the feminist movement's most visible, public campaigns for consent largely concern themselves with ontology and signification. Suzanne Holsomback's workshops look at "what consent is, and what it's not", and tackle questions such as, "does it always have to be verbal?" (Holsomback 2013). Campaigns from Rape Crisis, similarly, parallel Reclaim The Night motifs of laying out what "consent" is and isn't, and what "asking for it" is and isn't. (ref flyers)

However, behind the scenes, the more radical question of grammar is up for debate. Arguments for a re-definition of the ontology of consent give us a useful 'way in' here. If "affirmative participation" is not an added extra but is built into the ontology of consent, then a parrallel shift in the relationships of the parties involved is implied. It is in this search for a better grammar of consent that the most interesting feminist theories of consent emerge - and where links to practices of radical democracy become most clear.

So far I have discussed consent as it relates to sexual negotiation. The close feminist scrutiny of what happens in the process of reaching consent in this context helps us to put other types of consent, collaboration and agreement under the microscope too. Here I will look at the example of democratic collaboration as it is facilitated by software. I'll use Kleinig's terms - the ontology, signification and grammar of consent - to look closely at which models of consent are at work in three online platforms, where 'consent' has been encoded for computation.

The three collaborative systems I'll look at are Wikipedia (built on the MediaWiki software), e-consensus, and Doodle. While designed for varied use-cases, what these systems have in common is that they accept input from various users, and allow users to co-ordinate that input by offering various ways of establishing consensus. All of them priviledge democratic negotiation, although each of them encode this process in slightly different ways.

How consent is encoded in 3 online systems

Doodle

Doodle is a clear and elegant example of a decision-making system which encodes 'common-sense' ideas about reaching agreement. Doodle lets anyone who knows the URL of a poll share their preferred days for a meeting, via a simple calendar 'polling' interface. Users of Doodle aren't consenting to anything per se - it is intended as an information-gathering tool to help a meeting planner chose the best date. However, it is an interesting example of the way that individual vs group preferences can be recorded and displayed. Its aim is to arrive at a consensus by consulting with each group member, and to arrive at a date which may not suit everybody, but which achieves the maximum possible overlap of individual preferences.

What is Doodle's grammar of consent? In any given instance a proposal can only be made by one person, the poll initiator. The initiator chooses which dates to include in the poll, thus delimiting the choices presented. For each date, participants have by default only two choices: to check the box (meaning, I can make it), or to leave it unchecked (can't make it). Checked dates turn green, unchecked dates turn red. The poll initiator can enable, if they choose, a halfway option 'Ifneedbe', which when checked displays orange. The single poll initiator therefore poses a question with various options, in line with the classical "yes or no" grammar of consent.

How is consent signified? For each date, users may check the box, or leave it blank. If no dates are suitable, the participant may save the form without checking any boxes, or click a button reading "Can't make it", which also submits the form blank. By implication, then, silence signifies not consent but the opposite; while agreement must be actively signalled with by the gesture of ticking the relevant box. Any more detailed ambiguity than 'Ifneedbe' must be recorded in a separate comments box below the poll, which is not semantically linked to it. The system narrows users' options in order to produce a clear numeric 'favourite'; thus the checked boxes can only be a rough guide, and not a reliable indication of felt preferences or desires.

Wikipedia

Wikipedia articles may be edited by many users, with the aim of arriving at a consensus on the text.

What is Wikipedia's grammar of consent? In Kleinig's terms, consent is given by A to B, for P. Here, P is any change to the text. B is the editor making the change. She seeks the consent of (plural) A, all other users. Wikipedia's grammar of consent thus conforms to a fairly conservative one in which consent is 'sought' and 'given'. However, it begins to stretch this grammar, as multiple users make proposals in an ongoing and collaborative process. A does not merely play the passive role of saying 'yes' or 'no', but is expected to be an active agent contributing her own changes if she disagrees. It is unclear whether A includes readers of Wikipedia who do not have an account on the site. Are they, by reading the text and not creating an account in order to change it, consenting to the status quo? This expectation of agency informs how consent is signified.

How is consent signified? In its policy on consensus, Wikipedia (2013a) states clearly that: "Any edit that is not disputed or reverted by another editor can be assumed to have consensus." A related essay linked from this statement, "Silence and Consensus" (Wikipedia Editors, 2013b) - though not a policy document - comments that "Consensus can be presumed to exist until voiced disagreement becomes evident... [because] In wiki-editing, it is difficult to get positive affirmation for your edits..." (ibid). Kleinig himself notes that signifiers are culturally-specific, and may include silence in some cases (Kleinig 2010, p.11). Because of this, "there must be a convention whereby consent given is recognized as such" (ibid). Wikipedia's policy on Consensus attempts to set in place this convention. However, this convention is not without controversy. The Wikipedia Essay "Silence Means Nothing" gives several examples of things that silence may signify other than consent: "polite disagreement", not having seen, or choosing to ignore an edit (Wikipedia Editors 2013c).

What is the ontology of consent? Because consent in Wikipedia is signalled by silence, there is no clear distinction made between the state of mind of agreement, and the act of giving consent. Indeed, the chronological version control of in wiki software means that the only active gesture available - making an edit - is one which signals /lack/ of consent to the status-quo.

eConsensus

EConsensus.org is a relatively new online tool to help activists organize. Within 'groups', group members can create and comment upon 'proposals' as well as creating 'decisions'. The image to the left shows the commenting options which are displayed next to each proposal. The current totals for each type of comment are shown. Clicking on one creates a new comment with that tag.

What is its grammar of consent? What is being consented to is clear on eConsensus.org - proposals are named as such and given a unique ID. Proposals are commented on, and ultimately consented to (or not) by group members, whose name is registered next to their consent (if given). It attempts to mimic face-to-face consensus decision-making used in activist groups, in which a proposal is presented, discussed, modified and ultimately consented to by all involved. It is notable that each proposal may be modified at any time - possibly creating confusion as to which version of the proposal the comments (and consent) below refer to.

What is the ontology of consent? Group users may comment upon proposals, and 'tag' their comment with only one option from this list: 'Question', 'Danger', 'Concerns', 'Consent', or merely 'Comment'. Consent must therefore be communicated as a clear gesture; writing a positive comment without tagging it as 'Consent' does not constitute consent. (Although users of the software may, of course, choose to implement their own conventions.)

How is consent signified? Consent is signalled by selecting 'Consent' from a dropdown list of tags (called 'ratings') when writing a comment on a proposal. The visual language used to display these tags is blunt. Comments tagged as 'Danger' have a red mark; comments tagged 'Consent' are bright green. 'Concerns' are orange, and sit in between Danger and Consent in the interface, creating a symbolic colour spectrum. (These are the very same colours that Doodle uses to encode 'yes', 'no' and 'ifneedbe'.) Unlike Doodle, eConsensus lets users decide how to tag their responses, rather than giving initiators the power to decide whether or not users will be able to express ambivalance ('Ifneedbe' in Doodle; 'Concern' in eConsensus).

It is interesting to note that it is not possible to give consent and to signal danger or concern in the same comment. 'Comment' and 'Question' sit at either end of this spectrum, apparently unrelated to the middle three options in their respective shades of grey and blue. There is no option to refuse consent, ie 'block' a proposal, as there is in conventional face-to-face consensus, or in the Doodle interface. The assumption in the system must therefore be that proposals are never final, and are open to modification as long as concerns or dangers persist. It takes the Wikipedia approach of assuming that a rejection of the current proposal should be expressed as a modification, not a refusal, and makes it technically impossible to say "no".

Towards a radical grammar of consent

Note: I might split up this section and intersperse the text with these examples rather than putting them all together. Could use to illustrate a spectrum from 'over-simplified/coercive' to 'more open space'?

When I interviewed Reclaim The Night organizer and facilitator Clare Cochrane (2013), she emphasised the need for both "simplistic slogans on marches" at the same time as a deeper, long-term exploration of consent. While defending the continued need for reductionist slogans, she articulated passionately the problems with this conventional model of consent. Of the conventional "B consents to A" grammar, she said,

"as a feminist, I want to scotch that. That's a simplistic notion of consent, which is that... one person says, "I want to do this, will you do it?", and the other person says yes or no. And if they say yes you go ahead and do it, and if they say no you don't. Ok, look, if that's as far as you can get in a certain situation, that's better than nothing. ...But a fuller understanding of consent is not just that one person is agreeing to what the other person wants. ...in the end all you've got is a signature." (Cochrane 2013)

My friend the artist Dave Young's (2013a) project "Yet Another Collaborative Editor" (YACE) shows how this conservative, outcome-driven grammar of consent can be encoded in tools for collaborative production - and illustrates nicely the coercion it produces. Through "a hyper-democratic system" (Young 2013b - collision talk), users can submit text to a collaboratively-written document via a web interface. The catch is that every submission must be voted on by every other user before another piece of text can be submitted, and if anyone votes 'no' the sentence is discarded. There is a strict time limit after which no more sentences can be added, and the document is saved for .PDF export. So: when a concrete outcome is demanded, when there is limited time with no mechanism for discussion, and when proposals are not modifiable, the undemocratic and coercive nature of our working grammar of consent is revealed. Young's description of YACE as "a hyper-democratic system" is thus not strictly accurate, reflecting the common but mistaken conflation of this perfunctory grammar with consent itself.

How, then, to reimagine this grammar? Thomas Millar's (2008) essay "Towards a Performance Model of Sex" gives us a useful starting point. For Millar, our working grammar (what he calls our 'model') of sexual interaction is to blame for the perfunctory signature-seeking of the "get a yes" attitude. As long as sex - and thus consent - are conceptualized as "a substance that can be given, bought, sold or stolen" (p.30), then the logic of the market will define acceptable standards of consent. These will necessarily be impoverished, because "in order for commerce to flourish it is necessary to have rules about when someone is stuck with the bargain they made, even if they regret it or never really liked it in the first place." (p.37). We must accept that "a deal is a deal, however reluctantly, grudgingly, or desperately one side accepts it" (p.37). This grim outlook is lent some support by the tellingly economic logic of Wertheimer's (consent to sexual relations) comment that "by adopting the principle that consent is (ordinarily) /sufficient/ to legitimize interaction, we encourage mutually beneficial interactions" (p.124). More bluntly, "we are not interested in consent as a metaphysical problem, but because it renders it permissible for A to engage in sexual relations with B. [In defining it] we ask 'what could do that'?" (p.146).

Of course, as activists we are free not only to ask what we should render permissible, but what we might render possible in a much broader sense. Getting beyond the conservative grammar of 'permission' opens up exciting possibilities for consent as a more radical model of equal collaboration.

In order to priviledge "affirmative participation", Millar (2008, p.38) proposes rejecting the view of sex as a commodity over which deals must be struck, in favour of a model in which sex (read: any social interaction) is a collaborative performance. "Like the commodity model, the performance model implies a negotiation, but not an unequal or adversarial one. The negotiation is the creative process of building something from a set of available elements" (ibid, p.38). Millar closes with some reflections on what this collaboration could look like: "The palette available to them [the musical or sexual collaborators] is their entire skillset... and the product will depend on the pieces each individual brings to the performance. This process involves communication of likes and dislikes and preferences, not a series of proposals that meets with acceptance or rejection" (ibid, p.39).

Rachel Kramer-Bussel (2008) titles her contribution to the same anthology, "Beyond Yes or No: Consent as a Sexual Process". She claims that "consent is not simply a legal term, and should encompass more than simply yes or no" (ibid, p.44). For her, "'consent' encompasses the ways we ask for sex, and the ways we don't. It's about more than the letter of the law, and... at its heart is communication." (ibid, p.43) In opposition to legal pragmatists such as Kleinig and Wertheimer, for Kramer-Bussel, /asking/ (as well as aquiescing) is part of consent. The gendered distiction between asker and consenter is erased here, in favour of "an open dialogue" (p.48) which echoes Millar's call for consent as a "collaboration" based on "affirmative participation".

What is most striking about these proposals for a re-worked grammar of consent (which I will call 'consent-as-collaboration') is that consent is no longer an outcome, but must be a process in and of itself. This is not surprising when we think, for example, of the differences between democratic systems based on voting, and those based on consensus. If the aim is a decision made collectively (instead of a 'yes'/'no' vote), then the proposal to be consented to can no longer be static and self-evident; it must be modifiable. The process of proposing, discussing and modifying a proposal therefore cannot be divorced from the ultimate confirmation of agreement. So what does this collaborative process of negotiation look like?

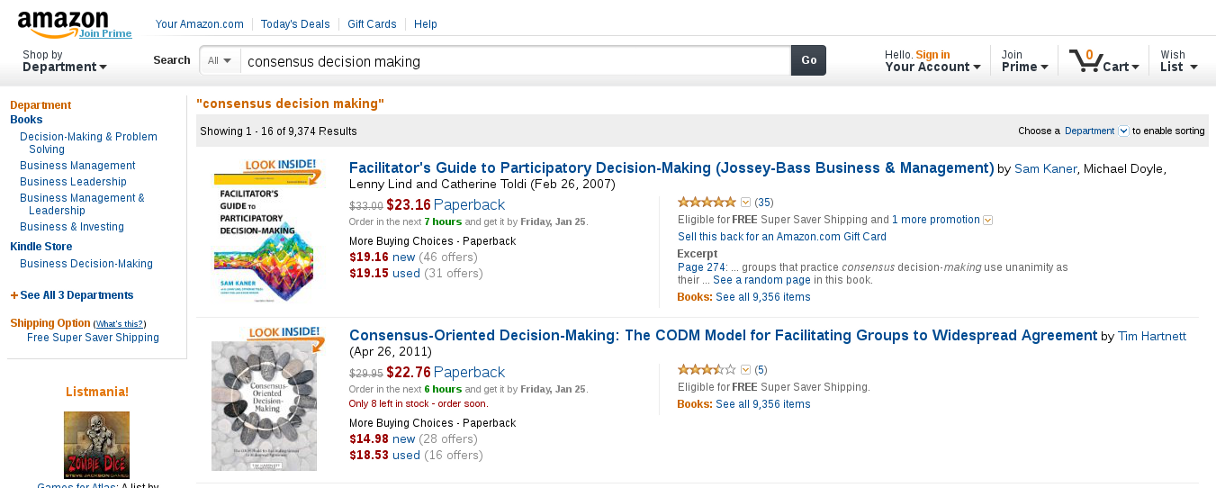

Notes: Two book covers on books about consensus

Search for 'Consensus Decision Making' on Amazon and consider the first two results (Amazon.com, 2013). One: Facilitator's Guide to Participatory Decision-Making. I first encountered this book on my lunch break while working as a facilitator at an activist charity. It is a familiar face on the bookshelves of friends and like-minded folk - a bible perhaps, outlining the process of reaching decisions consensually. The second is another consensus manual I don't yet know. It promises a "clear and efficient path to generating widespread agreement while fostering full participation and true collaboration" (Hartnett, T. 2013).

What struck me about these top two books was their covers. The first one features a colour detail of one of the book's key diagrams - the 'diamond of consensus'. So-called because the group begins from a point of affinity (a narrow, huddled zone), and through the process of decision-making airs its differences, desires and conflicts (a wide zone of deliberation, dubbed "the groan zone"), finally to converge narrowly again, upon an outcome agreeable to all. It is this last phase which is privileged on the cover of the second book, in which a circle of stones are aligned in such a way that each one's individual marking connects to the others to form a coherent and peaceful pattern. Individual difference is subsumed by the eye's desire for the striking circular pattern. The smooth restful pebbles of meditation books and motivational calendars: harmony, peace and unity. The 'clear and efficient path'. By contrast, it is the central 'groan zone' that is privileged on the cover of the other book, in full exuberant colour. It is a jagged space of zig-zag lines, in strongly contrasting (though complementary) colours, peopled by isolated dots jostling for attention, and rendered in watercolour and wax which resist each other.

I tracked down the illustrator of this book cover, Karen Kerney, who explained her inspiration:

"I was currently working in a whole grain baking cooperative, daily dealing with group dynamics and decision making so I had a keen interest in the subject. My illustration tended to reflect a group going along in the river of life...flowing along... When the issues arise that need a group's attention, I think that life gets bigger (like the diamond shape)...every thing is expanded...energy levels rise...creativity flows... If we handle the chaos and confusion as a natural integral part of the decision making process (not to be avoided), we build skills, trust, experience and come to know that we can move forward and evolve as a group. This was my experience at the bakery..." (Kerney 2013)

These two book covers offer two contrasting visions of consensus process, and thus, perhaps, of consent itself. On the one hand, the egalitarian harmony of the perfect circle; on the other, a space containing difference. The latter, argues Kerney, is necessary for the former - there can be no consensus while "chaos and confusion" are suppressed. Perhaps these two illustrations also offer two contrasting justifications for attempting to establish consent. It is easy to endorse a process for its 'efficient path' to an outcome everyone will agree to. (Scroll down your Amazon results for plenty of business books stressing the "high commitment decisions" and "problem solving" offered by consensus decision-making - echoing the feminist rhetoric that "consent improves your love life" (find quotes)). But I am arrested by the Facilitator's Guide cover and its insistent, proud privileging of this colourful groan zone. This zone is a means to an end, for sure, but as Kerney explains, that end may not be the obvious one of a harmonious group decision. In this wide diamond, in this wax and watercolour confusion-zone, lies another way of thinking about our dealings with others. On the cover of this edition it is cropped before the diamond closes and convergence happens. Perhaps this is OK; perhaps this closure is sometimes a shame. Perhaps the groan zone could be an end in itself.

Adopting the consent-as-collaboration approach poses a similar challenge to the one that consensus decision making does. It challenges us to enter a space in which the outcome has not yet been articulated, let alone decided. It demands that we enter a negotiation without either 'seeking' a yes or merely 'giving' one, but creating something cooperatively. (quote D. Sokolov on contracts vs collaboration) This phase is referred to as the 'Groan Zone' by the Facilitator's Guide for good reason. If the discussion is allowed to continue past the 'clean' outcome of a vote, and people begin negotiation in earnest, things get much more difficult.

It is necessary to draw a distinction at this point between consent-as-collaboration, and consensus decision making. In consensus, the aim is to exit this zone with an outcome agreeable, if not ideal, to everybody. For feminists, by contrast, the aim of consent is to avoid unwanted outcomes - even at the cost of indecision and inaction. ("Maybe also means no" - Holsomback workshop materials.) Consent, and especially consent-as-collaboration, demand an exceptionally high tolerance for the Groan Zone, with no guarantee of agreement at the end.

As Millar (2008) says, our attachment to perfunctory and problematic grammars of consent comes from the imperative for "commerce to thrive". By contrast, consent-as-collaboration demands an open space in which outcomes are not pretedermined; in which no eventual "deal" is guaranteed. We shouldn't underestimate the demand made by this approach. Resistance to the spectre of indecision and inaction that it raises is strong. This was illustrated to me by a man I met once on the street, who rebuked me for calling him out on his sexist harrassment. If it weren't for behaviour like his, he claimed, human reproduction would cease. I owed my life, literally, to a cultural disregard for consent. This sentiment is echoed less baldly by the comments heard by Holsomback (2013) in her consent workshops: "that's not something I want to bring up, it kills the mood." Holsomback's reply, typical of the 'consent is sexy' approach, is telling: "I'm like, 'no it doesn't, raping someone will kill the mood'" (ibid).

When I asked Clare Cochrane (2013) what connection (if any) she sees between her work as a consensus facilitator and her feminist work on consent, she said, "it's about making space. ...In all the things I do, what I'm trying to do is make space for dialogue." Why, I asked, is 'making space' so important? "For consent and for consensus, when you've got a safe and held space, you can let go of outcomes." I countered that it is precisely its inefficiency in producing outcomes that is the chief criticism levelled against both consensus, and feminist demands for consent. She replied that not only is risking the outcome better than risking coercion, but "if you let go of outcomes and you can really be in a process (in either consensus or in a consent situation), then actually [the outcome] is more beautiful" (ibid).

Holsomback and Cochrane employ elegant and irresistible paradoxes: avoiding 'killing the mood' with non-consent kills the mood; letting go of outcomes delivers better outcomes. This may be true in some contexts. But the problem with this approach is that consent can "kill the mood". In Kerney's terms, "chaos and confusion" are "a natural integral part of the decision making process". And not only can a genuinely consensual discussion "kill" the elusive "mood", it may well rule out your desired outcome - or any outcome. I think glossing over these facts misses a valuable opportunity. By stressing that consent-as-collaboration produces better outcomes, we are co-opted by the old instrumentalism which stops us appreciating that a tolerance for the Groan Zone, and a commitment to "space for dialogue", may themselves be the winning features of feminist consent.

Any system that encodes consent-as-collaboration must therefore encode a tolerance for difference, indecision, and inaction. This poses a problem if we propose applying such a decision-making process to publication design - which, by its nature, involves the elimination of most of the options ("sea of content") to produce a singular outcome (edited "best-of"). For example, the Be The Media collective must decide which RSS feeds to pull in, and how to arrange their content in the limited space of a webpage. This imperative for decision is intensified in print, on a paper page which cannot avoid editorial decisions though dynamically served content, overlays or user queries. The withering phrase "design by committee" is traditionally levelled against those processes which fail to understand that indecision and compromise do not work in this context. But if we understand consent as a process of dialogue, then to 'agree to disagree' is a valid outcome. To agree to do nothing, or to do nothing now, or to continue talking - all of these are, in fact, decisions. Could these decisions count as such in the context of publication design, though? 'Agreeing to disagree' or 'deciding not to decide' is a rich ethical approach; could it be an aesthetic one too?

Notes: Playing Gutenberg - Collision 1, Brussels

This February I was fortunate enough to attend the first 'Collision' worksession in Brussels, organized by Pierre Huyghebaert and others of the Libre Graphics Research Unit and Constant. The meeting was an attempt to critique, and explore alternatives to, the logic of conflict resolution underlying conventional graphic design practice, and the collaborative tools it gives rise to. An introductory text summarizes, "Maps, schematics and books are complex graphic surfaces where meaningful elements fight for space in different dimensions. ...design is essentially the work of organising collisions. In a conventional design practice... tension is deflated through erasure, simplification and filtering. What would be ways to articulate collisions, instead of avoiding them?" (Huyghebaert 2013a, collision blog)

While this is a highly formalist brief, there is a clear ethical imperative behind this line of questioning. Mapnik, the graphical engine used by Open Street Maps, is given as an example: "If a streetname doesn’t fit, it disappears from the map; if there is a conflict, contributors are advised that it all comes down to a simple choice: “yours or mine”." The conflict between competing graphical elements, then, stands in for a conflict between people. Femke Snelting summarized this adversarial approach: "If it collides, erase. If it doesn't fit, take it out." (LGRU 2013a, introductory discussion) Parallels with a black-and-white discourse of "yes or no" consent are immediately apparent ("if they say yes you go ahead and do it, and if they say no you don't" (Cochrane 2013)).

The tenacious assumption behind the Collision project is that digital tools (and ways of thinking) undermine the necessity of this approach. (Footnote: see booklet '16 case studies re-imagining the practice of layout'.) "We can begin to rethink layout from scratch. So what is scratch? What is at the bottom of it? I think the bottom of it is Gutenberg", said Huyghebaert. Framing the question as one of historical progress, Huyghebaert expressed his frustration that graphic designers are still "playing Gutenberg... playing printer with little squares & rectangles. The separation that started with Gutenberg between the writing, which is really square, seems not useful anymore." (LGRU 2013a)

The analogy between lead blocks, which cannot co-exist in the same slot, and social proposals, which must be reduced to winner/loser, is a striking one. The Collision project attempts to articulate how we might get beyond this mode of thinking. And, crucially, it doesn't require that we fetishize digital media or conceptualize it as opposed to paper. The reductive box-model described by Huyghebaert started with Gutenberg; the implication is that a digital - as in hand-made - approach could be just as liberating as a digital - as in computational - one. As Ludovico notes, the opposition between (static) paper and (manipulable) digital media is a false one (see POD discussion, Ludovico PDP p.77). While paper is not analogous to screen (PDP p. 117), 'hybrid' publishing models (such as print-on-demand) mean that printed objects are increasingly (in)formed by computational processes. (Ludovico, Liberation article) This means that we can use 'digital' ways of thinking to approach design conflicts which are not, after all, inherent to the printed medium but in fact arise from social and historical assumptions ("playing Gutenberg").

The first workshop I attended during Collision 1 illustrated this point nicely. Showing us his favourite toy, a plotter printer, Gijs de Heij facilitated a battleships-style game in which two teams plot circles on the same sheet of paper, attempting to avoid 'collision' by not overlapping the other team's shapes. De Heij's custom browser interface allowed us to draw, or write text commands, in real-time, and see our designs rendered instantly by the plotter pens moving over the paper. The game was difficult - owing to the various layers of mediation between our bodies and the page. But importantly, it was also pointless. A plotter - which can go back and re-work the same surface in a fluid way impossible with a laserjet printer - lets us re-imagine the printed page as an open space where interactions can occur, rather than a grid in which lead blocks compete for their share.

The second workshop took a more digital approach to the same problem. Christoph Haag's 'Forkable' creates a (digital) space for multiple design options to co-exist. We were invited to clone a repository containing an image file (an SVG reading 'Badness and Conflict'). Each letter of this text was stored in a different layer of the SVG file, meaning it could be independently manipulated. We were invited to make and save changes to any or all layers, and add our version as a new file to the repository. Thus, multiple versions of the same file existed, with various possible permutations. Rejecting the imperative to chose one over another, this 'conflict' is resolved by a Bash script which picks layers at random from each SVG contributed, re-combining them each time the script is run. One time my version of the letter 'M' may be included; the next, yours may be.

On the final day of Collision 1, I spent the day with Femke Snelting and Pierre Marchand researching a real-world example of collision: the choice of which metadata to render on Open Street Maps (OSM). While anyone can contribute metadata to the OSM database - for example, describing a route as a 'footpath' or a building as a 'shop' - only certain tags are rendered on the official OSM website. Footpaths and shops will be labelled; but if you've tagged a place as a gay cruising area, don't expect that to show up. While Haag's 'Forkable' simply picks at random which options to include, the decision about which OSM tags to render is a complex, quasi-democratic process. There are various interest groups lobbying for their tags of choice to be rendered in the official map - presumably so they don't have to render and host their own versions. Amongst these are the proposal to tag adult shops, and the proposal to tag gay-friendly places. The latter has been proposed by Open Queer Map, a group who are already actively adding metadata to the OSM database indicating places which are gay-friendly. While this metadata is stored in the OSM database, it is not rendered on the official map, and Open Queer Map currently have to render and host their own map in order for this information to show up. There were several people present at Collision 1 who argued that, instead of 'cherry-picking' the most important tags - resulting in the current scenario of lobbying an elite of programmer-curators - OSM should be providing an interface which lets users, not OSM programmers, decide which metadata to render. We should not have to go to several different maps to get all the information we need, but be able to browse the appropriate information through a single interface.

In both the Forkable workshop, and the debates about Open Street Map, an approach emerged which offers possible answers to the question of whether indecision could be a viable design methodology. Indecision needn't mean paralysis, deadlock, or mediocrity. Instead, it could mean provisionality. In each iteration of the Forkable SVG, different people's versions will 'win'. Just as, if OSM gave users the power to chose which metadata to render, each map would still render only a limited range of this data. The difference is that that the decision is not final, and the algorithm used to arrive at the decision is made visible.

There is a danger, of course, of such an approach returning to the 'filter bubble', and serving users a customized pick of the crop. But it needn't go this way. In the Forkable repository, all iterations are visible, and it is clear that running the Bash script will simply produce one of many possible permutations. Similarly, the simple act of looking through the list of OSM tags and seeing which ones are in use allows us to see any given rendering as a provisional and partial snapshot of the database as a whole. In this approach, the 'competing' versions are all retained and on view; not discarded or hidden by the algorithms that create outputs from them. And this approach needn't rely on digital media or database queries. Other groups at Collision 1 produced paper prototypes rendering 'indecision' using techniques such as origami-like folded paper maps to allow multiple layers of information, cross-hatching to depict overlapping geographical zones, and so on.

These examples give concrete graphic form to the feminist proposal of consent-as-collaboration, in which negotiation does not consist of successful or unsuccessful proposals, but an open space in which possibilities are communicated and can co-exist.

[ how does this relate to work of art digital manipulation - query as re-introducing benjamin-like 'aura' as each query is unique? ]