User:Mania/thesis-draft: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 30: | Line 30: | ||

INTRO | INTRO | ||

In | In cities where everything is meant to run smoothly, be predictable and instantaneous, we pass each other by, enclosed in our own untroubled worlds. What is happening on the street, between promises of luxury, next to shiny modern buildings? What do we not see? With this text I look for unsmoothnes, disruptions of routine. Through these random combinations of people, locations and what to pay attention to ( FOR PEOPLE… / TO SEE…/ IN…) I embark on a search to find those cracks in polished image of the city. I have fun unfolding little details at street level and narrating them in artbook format. And these random prompts spark my imagination as they converge into unusual combinations that reveals more the messiness that interests me. I want to touch on something rather seamfull, not calculated and predictable, those moments of collision and exchange. Valuing randomness and play, this text is driven by an intention to delve into the question of connection. '''How connection with others through play and careful observation can provide a way of resisting the alienation?''' | ||

Embracing friction, surprise, and play is a way of pushing back against the alienation often found in modern cities. Slowing down is a form of resistance. In this context, I treat play as a tactic, an approach to fostering connection, expressing freedom, and resisting the pressures of constant productivity. | |||

This began with a desire to look with curious eyes, not just to be a witness, but to actively take part. To see the city as something that can be read suggests that it can also be rewritten. It is something that we not only discover but also make. | |||

This text weaves together my observations with other texts, turning writing into a dialogue with walking, collecting, and experiencing the city. It invites you to slow down, to notice, and perhaps to play. | This text weaves together my observations with other texts, turning writing into a dialogue with walking, collecting, and experiencing the city. It invites you to slow down, to notice, and perhaps to play. | ||

== Chapter 1 == | == Chapter 1 == | ||

Revision as of 15:38, 8 April 2025

A TOOL

FOR PEOPLE

TO SEE

INTRO

In cities where everything is meant to run smoothly, be predictable and instantaneous, we pass each other by, enclosed in our own untroubled worlds. What is happening on the street, between promises of luxury, next to shiny modern buildings? What do we not see? With this text I look for unsmoothnes, disruptions of routine. Through these random combinations of people, locations and what to pay attention to ( FOR PEOPLE… / TO SEE…/ IN…) I embark on a search to find those cracks in polished image of the city. I have fun unfolding little details at street level and narrating them in artbook format. And these random prompts spark my imagination as they converge into unusual combinations that reveals more the messiness that interests me. I want to touch on something rather seamfull, not calculated and predictable, those moments of collision and exchange. Valuing randomness and play, this text is driven by an intention to delve into the question of connection. How connection with others through play and careful observation can provide a way of resisting the alienation?

Embracing friction, surprise, and play is a way of pushing back against the alienation often found in modern cities. Slowing down is a form of resistance. In this context, I treat play as a tactic, an approach to fostering connection, expressing freedom, and resisting the pressures of constant productivity.

This began with a desire to look with curious eyes, not just to be a witness, but to actively take part. To see the city as something that can be read suggests that it can also be rewritten. It is something that we not only discover but also make.

This text weaves together my observations with other texts, turning writing into a dialogue with walking, collecting, and experiencing the city. It invites you to slow down, to notice, and perhaps to play.

Chapter 1

A TOOL

FOR PEOPLE

TO SEE

In this chapter, I am looking for ways to "read" the city, that which welcomes a different pace and different ways of being in space. I am searching for methods that allow perceiving the urban reality from multiple viewpoints. To shift perspectives, embracing other ways of engaging with our surroundings. By playfully defamiliarising the familiar, these methods have the intention to challenge the narrative of urban space as smooth, efficient and at the service of productivity.

My fascination with framing started this summer, with a pair of binoculars I bought at a market for three euros. Totally absorbed, I spent hours observing the rooftops of Sofia—textures, antennas, and edges. Gradually, fragments of the city revealed themselves to me. Serendipity played a role in these observations, and I couldn’t have been happier, as I noticed things that usually go unnoticed. The binoculars became my tool for reading the city and found a permanent place in my routine. With a newfound interest, I scanned buildings, gliding along their lines. They made me notice houses that look like they are hugging the one in the middle. Passersbys entered and exited my frame, suddenly, the city became full of surprises. I became obsessed. Through them, I observed Sofia, Warsaw, Frankfurt-Oder and Słubice, Rotterdam, and Groningen. It fascinated me how even the simplest tool, with its inherent limitations, could be an opening for so many surprises. What I mean is all the things I have seen before but ignored. I find it intresting how narrowing the field of vision, allows for looking at the city piece by piece and brings a specific fragment to the front.

Reading the city isn’t just about observing it from a distance. The more I observed, the more I realized how complex and multi-layered cities are, interwoven with countless stories. Reading a city means being genuinely curious about its people and surroundings.

It involves being open to unexpected opportunities that arise IN unfamiliar streets / IN shadowed corners / IN familiar spaces / IN chaotic streets /IN the spaces in-between / IN spaces of certainty / IN neighborhood park / IN museum courtyards / IN crowded markets / IN city squares / IN quiet side streets / IN leisure spaces / IN shared spaces / IN spaces full of people…

It involves noticing who is around you. There are PEOPLE always in a hurry / PEOPLE who sing to themselves / PEOPLE who take detours / PEOPLE who carry notebooks / PEOPLE lost in their thoughts / PEOPLE who bike everywhere / PEOPLE who dream vividly / PEOPLE who miss their hometowns / PEOPLE who never stop questioning / PEOPLE walking alone / PEOPLE who enjoy getting lost / PEOPLE who love surprises / PEOPLE who stay up late / PEOPLE who speak with their hands / PEOPLE who feel out of place / PEOPLE walking slowly / PEOPLE speaking many languages…

Perhaps we take these spaces for granted, moving through them daily without much thought. But maybe we can learn to see them differently: TO SEE the long way home / TO SEE the stories in gestures / TO SEE the endless possibilities / TO SEE the rhythm of the city / TO SEE the connections / TO SEE the hidden textures / TO SEE the passing time / TO SEE the absurdity / TO SEE the hidden shortcuts / TO SEE the unexpected / TO SEE the structures / TO SEE the stories / TO SEE the choices in how we move / TO SEE the city’s edges / TO SEE the city as a game / TO SEE hidden playgrounds / TO SEE new paths / TO SEE the absence / TO SEE what’s written in the street / TO SEE the extraordinary in the ordinary. Then, nothing will stop us from reimagining these spaces. I believe the first step is to pay attention.

I decided to build a camera obscura large enough to step inside and place it in public space. I was curious to see how our perception changes when we view an image upside down. Would we notice something extraordinary in what we see daily? Unfortunately, the costs of constructing such a device overwhelmed me. Instead, I realized this idea within the confines of my room. Using cardboard and the properties of light, I transformed my room, already positioned on the street, into a camera. I darkened the entire space, leaving a pinhole to create an inverted image. On my table, I saw a fragment of the bridge where train tracks once ran. At that moment, I knew I was inside the camera. The projection was smaller and blurrier than I expected, yet I observed the bridge fragment with a level of attention I’d never given it before. For two years, that view had been the first thing I saw when opening my door. It wasn’t until I saw it upside down that I truly paid attention. The camera obscura flips the image, and much like binoculars, it allows me to see it with a renewed sense of interest. I read the city upside down. I continued observing my surroundings. For days, I sat in a square, observing at specific times. I watched my street through the frame of my window. I built a device — a tube – for reading the city. I watched the city through a paper frame, a camera, and a film camera lens. I became an expert observer.

In the book Screen-Writing 1995 by Scott MacDonald, I come across a series of mini scripts for films created by Yoko Ono. Yoko wrote them between 1964 and 1968 while she was involved in the Fluxus movement, which emphasized artistic experimentation and the creative process. The scripts were meant to serve as a kind of "score," intended to be shared with other filmmakers so they could create their own interpretations based on them. One of the scripts was Film No. 13 (TRAVELOGUE), in which Ono proposes a script for a story about a visited place told from the perspective of a person who can only see in close-ups.

“For example, you introduce Tokyo and explain that what you see there are just knives-only because you focused in on a knife shop and that became Tokyo to you.” (MacDonald, citing Yoko Ono, 29)

The example of Tokyo reduced to "knives" shows how the perception of a place depends on what we focus on, how subjective this experience is. I wonder what other interpretations would look like. What would Tokyo described only in close-ups be for others? What do we not see, but happens next to us? What happens when we really look around? Why don't we even look at each other, but when we do it is intimidating? We live in a world where everyone seems to function in their own, separate bubble, disconnected from others. We move around the city, following our own, detached rhythms, and despite apparent closeness, we experience loneliness in the crowd. In such a reality, the attempt to gather individual fragments into a whole and notice the relations between them seems particularly important to me. A view that allows for the connection of independently existing fragments into a wider network of connections.

Karolina Wolszczak is a visual artist based in the Netherlands, in her project Walking with Speculative Artefacts in Public Space in Amsterdam, objects found at street level and imagination allow her to explore the layers of the city. As she walks, she searches for traces that have so far remained invisible, collecting objects often seen as dirt and inviting others to do the same during workshops. This process later involves imprinting artifact traces in clay and sharing stories with participants of the workshops. In a way, this puts the found artefacts in dialogue with each other, noticing relationships that were previously unnoticed.

“We should walk repeatedly and focus on the debris of everyday life. We should sometimes slow down or even stop, extend our antennas and listen to our surroundings through our various senses. For new possibilities of a common future, we desperately need new interpretations, voices of other-than human narrators, shifts of perspective, disturbances of logic to open our imaginations. To connect already existing dots, before invisible. Perhaps the hint is not logical, singular, nor clear. Perhaps the hint is collective, civil, intuitive, and speculative. It is the voice out of I, out of time and gender, and the plurality of the broken artefact(s)” (Wolszczak Page 69)

The artist speaks in favor of the need to notice narratives that escape the one dominant story. These small, seemingly insignificant objects nurture curiosity. By dedicating attention to them and imagining the stories they carry, Wolszczak unveils fragments of interconnected places. She also encourages us to slow down in our interaction with space. Interaction against the hyper-efficient logic. She suggests that knowledge can also come from open interaction and mutual exchange, from a collective way of experiencing and interpreting the world.

The point is to go beyond a rigid point of view and create space for understanding and closeness. In the project “Walking Beyond Words” Sally Stenton explores how words can generate different experiences during walking, opening new ways of engaging with surroundings. The project involved creating prompts for walks - one for each week, for example "The walk dances around you”. Even though the participants of this project go alone, they gain a certain feeling of belonging -“solitary companionship” - as the author calls it. Although they walk alone, they realize that others are doing the same in parallel, that they are part of a group experience. Despite the physical distance, the prompts strengthened their sense of belonging. The experience initiated by the prompts was documented in the form of poetry collages. Collecting words from others after the walks helps build narratives from the perspective of not just I, but a collection of voices that together see more broadly.

Imagine moving through space where curiosity, rather than efficiency, guides your journey. Not traveling in the most effective way, but following a playful script. What situations might arise along the way? I'm curious about how words can initiate a different way of experiencing the city, one in which unpredictability plays an important role. I continued this exploration by juxtaposing different combinations. I was deeply inspired by the work The House of Dust by Allison Knowles (1967). This work used a script that juxtaposed words into random combinations. It began as a computer-generated poem but didn’t remain just that—Knowles, associated with the Fluxus movement, interpreted these combinations and translated them into architectural forms. By playing with text and performance, the poem became a score, open to interpretation. (Knowles, 1967)

I prepared a script that selected entries from various categories and combined them to create prompts for participants in my workshop to build their own paper tools that favored playfulness over efficiency. Something that doesn’t serve a practical purpose but instead stimulates imagination, and invites us to engage with space from a new perspective. Tools we have built included:

A TOOL FOR people who love surprises TOO SEE the hidden textures IN unfamiliar streets

A TOOL FOR people who speak with their hands TOO SEE the city as a game IN the shadowed corners

A TOOL FOR people who bike everywhere TOO SEE the stories in gestures IN shared space

A TOOL FOR people always in a hurry TO SEE the passing time IN an open park at night

A TOOL FOR for people who adore symmetry TO SEE the stories IN a place full of people

Participants using the properties of paper prepared simple objects, determining unconventional routes. These seemingly funny paper tools turned out to be an effective invitation to play. I come to the conclusion that the best way to look at the surroundings I know by heart is to observe weirder and try different tactics. Perception is not fixed. It can change and evolve, and in fact, it takes action. These methods became helpful not because of their mere functionality, but because they turned out to be playful. I used computer to generate a random combination, this technology initiated the experience of space differently than in everyday life. Play opened up space for exploration, allowing us to see the city as more than just functionality.

I use this script in my further observation of the city. Through these random combinations of people, locations and what to pay attention to ( FOR PEOPLE… / TO SEE…/ IN…) I embark on a search to find cracks in polished image of the city. Putting these fragments together in prompts I treat them like metaphors that stimulate my imagination. They make me open my eyes to other people in space, to other objects and experiences. And even though these fragments are incomplete and put together imperfectly, they are held together by an attempt at a more holistic view. And although I will not step into the skin of others, I will not share their experience, these random juxtapositions hold the intention to reveal fragments overshadowed by the main urban narrative of productivity and competition.

By welcoming multiple points of view, by shifting perspectives, space opens up for a new way of seeing, for attentiveness and closeness. And suddenly, the city reveals itself as more than just work and haste — it becomes a place for other, more tender forms of presence. Through a playful reimagining of the familiar, these methods seek to challenge the prevailing view of urban spaces as seamless, efficient, and focused solely on productivity.

.

FOR PEOPLE who miss their hometown

TO SEE the absurdity

IN spaces in between

Chapter 2

FOR PEOPLE who always carry a notebook

TO SEE the choices in how we move

IN open spaces

This chapter explores how play can push back against the pressures of constant productivity. It talks about play not only in space but also with space and its established norms. By reflecting on the Situationists’ spontaneous drifts, Fluxus walking scores, and the way skateboarders repurpose urban environments, I argue that play challenges conventions and can serve as an act of freedom.

I had a dream in which I had an overwhelming feeling similar to living in a clock…

The feeling that I am the hand of a clock, racing to strike the exact hour. That I constantly have to chase the larger hand and follow its rhythm, and I can't keep up. 8:00 AM in that world doesn’t mean waking up from a blissful sleep, but rather repetition, blurring the line between today and yesterday. At 8:03, I am already standing ready to fulfill my duties, smoothly moving across the clock face. And so, I diligently continue the task assigned to me until midnight, when I will set off once again for another turn around the dial. The other clocks in this world of clocks also consist of isolated hands that form a community of isolated inhabitants. The hands in this world have one task: they only move to the right, creating a predictable choreography. When I slow down in an act of disagreement, simply wanting to wait for the longer hand at 3 PM, it doesn’t take more than fifteen minutes before a human notices, grabs the clock from the wall, and sets us back in readiness...Would anything really happen if at 3:00 PM time slowed down for a moment?

I already think it will happen at 12:00 – the two hands meet for a moment in the same position, rhythmically striking “kuku kuku" suggesting lunchtime, a break, rest. But that moment when we sing “kuku kuku" doesn’t sound like a shared melody but rather like voices that drown each other out.

I wake up and think of a clock hand trapped in a very repetitive life, dreaming of knowing spontaneity and play. If modern cities prioritize functioning like a clock, efficiency, and productivity, then they must be predictable. They rely on repetition and an uninterrupted rhythm. In Urban Play, the authors suggest that if modern cities, driven by algorithms and predictability, had to be represented by one symbol of efficiency, it would be an urban managment dashboard. (Duarte, Alvarez, XII) In a way a control panel for managing the city that prioritizes order, data, and optimization over spontaneity and human experience. Everything runs smoothly, clean and is designed for convenience. Observing how digital technologies make services instant, everything happens immediately and basically without leaving home I realize these services are seamless and fast, but at the same time, they tighten control over public space. This convenience happens at the cost of spontaneity and diversity. I am reminded of the text Smooth City by René Boer, which has greatly influenced my thinking about the city. He discusses how contemporary cities prioritize order and efficiency, calling this state smoothness. No surprise, after all, it is characterized by being frictionless. The humorous collages accompanying the book joke about this perfect environment, mixing surroundings that seem almost staged. Shiny clean spaces bearing witness to comfort, gleaming elements, happy people, steel and glass, convenience, and at every step, advertisements whispering promises of luxury. In a city so focused on success, achieving, gaining and improving everything to function faster, better and more, difference and unpredictability become flattened. This way, the city serves the needs of a selected group. Boer stands for more open places. Places that allow for resistance, creativity, and real human connections.

In the movie Playtime in which Tati satirises how modern cities try at all costs to be efficient but end up feeling alienating. The main character gets lost in a city of steel and glass, a city filled with technology. The film does not have a single plot but rather presents many different characters as they move through a futuristic city. Their behaviors are so well orchestrated that it reminds me of the animation Tango by Zbiegniew Rybczyński (1981), in which the action takes place in one room, into which characters enter and leave, each busy with their own activity, repeating their actions, and not getting in each other's way. Similarly, in the Playtime movie, the characters were isolated and I felt like I was spying on them, even though I would have preferred to be in dialogue with them. This automation, confusing technology, identical buildings, and this rawness felt terribly cold, while I would have preferred to know what these characters were thinking. The film shows a controlled, rigid city where technology is supposed to make life easier, but often alienates the characters. Only at the end the characters break away from this order, reminding us that we can't work non-stop and be productive all the time. Reminding us our deeply human need for spontaneity and play. Even the most efficiently functioning "management dashboard" will not replace the pleasure of random encounters with familiar faces on the street, the delight of lounging around in the park, the jollies of rolling down a hill, the surprises that come with getting lost in the city, and, finally, the experience gained from mistakes made.

Embracing friction, surprise, and play can be seen as a way to express freedom, and push back against the demands of constant productivity. In contrast to the logic of the capitalist city, which expects people to move with purpose, following a route between work, home, and shopping, the Situationists organized aimless wanderings, rejecting structured movement and encouraging free exploration of the city. The Situationists were a radical group of artists, intellectuals and activists that emerged in Europe (primarily in France) in the late 1950s and 1960s. They criticized how modern society had become controlled by consumerism. They explored the way people move through the city and interact with it, looking for opportunities to create situations that would disturb the poignant routine. They drifted from place to place, guided by their emotions and curiosity, not by work and profit. These wanderings took up a lot of time. In a world where time is treated as a commodity, Debord suggested an entire day of aimless roaming. (Sadler, 93-94). Such an activity was effortless, making it easy to invite others to walk together, and it didn’t cost anything. It became an unproductive, yet very social activity. The Situationists preferred to set out on their drift in small groups of people, which were far from resembling the masses of passing tourists. In The Situationist City, Simon Sadler connotes what Debord wrote;

”A loose lifestyle and even certain amusements considered dubious that have always been enjoyed amongst our entourage—slipping by night into houses undergoing demolition, hitchhiking nonstop and without destination through Paris during a transportation strike in the name of adding to the confusion, wandering in catacombs forbidden to the public, etc.— are expressions of a more general sensibility which is nothing other than that of the drift,” (Sadler, 94)

The intentional act of play and spontaneity was treated as a form of resistant to the alienated way of living imposed by capitalism. The drift was meant to show people an alternative way of functioning, one that leaves more room for unpredictable moments. Just like the hand in the dream, which, by stopping, wanted to slip out the prison of the clock, urban drift aimed to break free from the routine of the commodified world. Drifting has become an everyday resistance to the alienation that is the result of capitalist cities, a call to reclaim everyday life overtaken by the influence of capitalism.

I observed how city planning and street signs dictate movement and navigate us through space, giving the impression of being highly staged. I encounter constant prohibitions and orders.

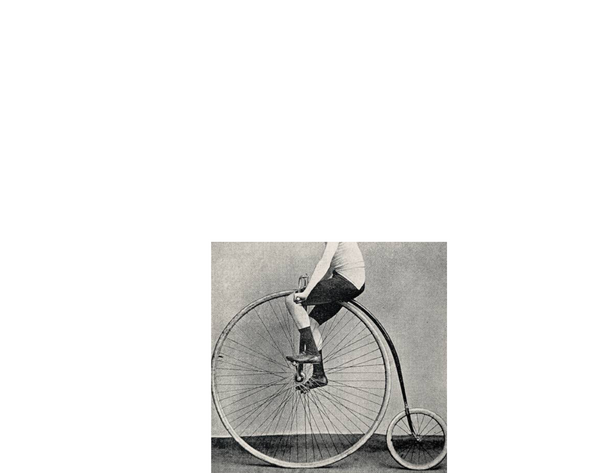

For example, a "no playing football" sign in a place that seems perfect for such an activity. Is play and unscripted behavior welcomed in the city, or are they viewed with reluctance, or even discouraged in favor of order and control? The absence of excessive control doesn’t have to mean a total lack of rules. Such rules or scenarios can, by design, be playful. Through fun, open prompts that encourage imagination, they can inspire exploration of space, improve physical awareness, and initiate creative actions. An example of this is the walking scores in Elina Biserna's book Walking from Scores, which explore how walking can be more than just a way to move through space. Open-to-interpretation scores stimulate curiosity and awareness of the surroundings. One example of a walking score by La Monte Young, "Draw a straight line and follow it" (1960), opens up the possibility of stepping beyond the familiar, memorized daily route and embracing chance. It reminds me of a scene from a movie, which title I can’t recall, where the characters decide to move through the city only along a straight line. To continue their path, they had to walk across the roof of a parked car in front of them. The straight line passed through the apartment of an elderly woman, which they courteously traversed to continue their swinging walk.

When I test my scores for moving through the city - walking 20% of my normal speed, hopping instead of walking, finding corridors between people, I often encounter suspicious looks. As a child, perhaps the first time I questioned social norms was when I engaged in a completely innocent dance around town and was met with judgmental stares from passersby. Now, doing this again in Rotterdam, one time while hopping along my street, a passerby joined me. Together, we joyfully crossed a few blocks. Play doesn’t need to be explained to others. All it takes is a pretext, and suddenly, you find yourself in a situation where you’re playing together. Basically, without doing anything serious, just by playing in public, people subtly resist the idea that urban spaces should only serve economic and functional purposes.

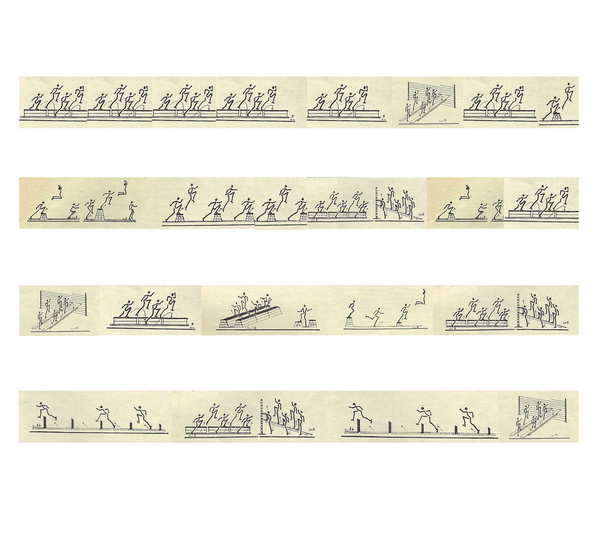

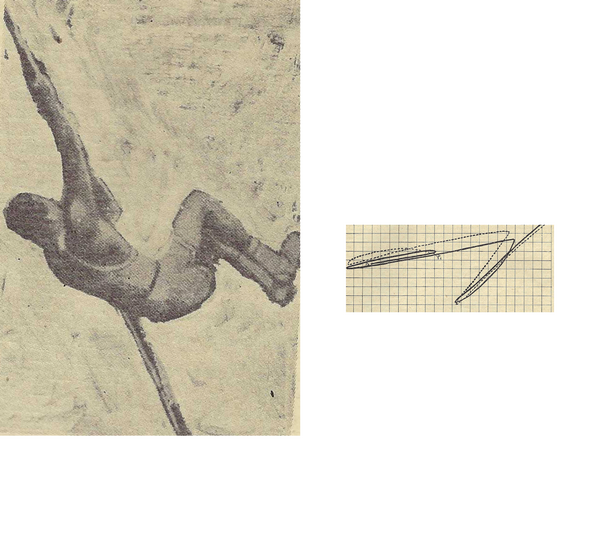

The script (randomly opposing locations, people, and things to pay attention to) that I follow in my urban exploration is a loose search for connections. It turns out to be playful, guiding me along different paths through the city. Trying to link dots between prompts: people who always carry a notebook / choices in how we move / open spaces I come across a market during my visit to Warsaw. And there, I stumbled upon old notebooks in various formats. Some blank, others filled with writing, they became like guides in space, since they filled me with desire to revisit certain places. Notebook belonging to a 4th-grade student, brought me to the park Pole Mokotowskie. In high school we would go there, when we skipped math class. In that same park, every year at school, we organized kite-flying competitions. We would gather in a big group, each with a handmade kite running through the grass. From a large container, I also dug out magazines on athletics, featuring sequential photographs and graphic representations of movement. By juxtaposing found movement scores with urban structures that dictate how we navigate, elements like curbs, restrictive benches, prohibitive signs, I imagine a jump from regulation to exploration. Photos of athletes removed from the context of competition, opened up the possibility of taking movement beyond the sports field and into the streets as play. Among these found treasures I found graphic representations of athletes' movements, these jumping figures looked like musical notes. I cut them out and arranged them into an urban choreography filled with play. The notes in the form of various doodles and lines became a record of the trace that play creates.

This reminds me of a scene I saw from the balcony of my previous apartment, where I could see the courtyard from above. Once I saw a girl there who was playing by moving a plastic chair that had been left there for the neighbors. These movements left something resembling an abstract drawing on the black gravel. Soon after, the traces disappeared, and the courtyard became empty again. The marks of play were replaced by the imprints of adult footsteps. Straight lines back and forth, suggesting that in the morning, they left for work, and in the evening, they returned the same way, hurrying to rest in their separate apartments. When I say "adults," I mean the neighbors whose names I never knew. I only knew their shoe sizes, imprinted in the black gravel. During play this courtyard transformed into a place full of possibilities. The concrete ledge surrounding its edges gained the potential of a jumping pad, became a shelter, a table, or an imaginary border separating two worlds - the world within the black gravel from the world of concrete paving. Children flashed across between these worlds. One would like to say that this space seemed to expand before our eyes. During the children's play, these few square meters were filled with various rhythms and meanings. Once the play ended, the courtyard remained the same courtyard, yet it faded, became quieter, as if it shrank back to its original size. And although physically nothing had changed in it, the feeling it carried was diametrically different.

The same is true for the other examples, such as skateboarders approaching space through play. They do not follow the functions assigned to street elements, but rediscover the space, finding completely new uses. A slippery railing can turn into a fantastic spot for tricks. A bench, stripped of its seriousness, becomes an open invitation to play. A low wall, a ramp, or stairs transforms into an unexpected playground, a source of surprises. Through constant exploration, this kind of play generates new ideas and possibilities for engaging with space. In this way, by not taking these assigned functions for granted, play breaks the established patterns and blind habits that dictate how we move through space and what behaviors become patterns. (Duarte, Alvarez 24).

According to Fabio Duarte and Ricardo Alvarez - authors of Urban Play "Play takes us away from our comfort zone, away from the ordinary rhytms, habits, and meanings that mark the way we relate with the world. By doing so, play transforms our relations with the world and, in its radical form, transforms the world altogether.”(Duarte, Alvarez 2)

When we engage in play, we interact with space differently. We break routines and patterns that judge us based on success and achievements. Play creates room for simply being human—in the sense of sensitivity, vulnerability, and imperfection. In a world where success is defined by work, deliberately slowing down through play—which, at its core, is unproductive—is a small act. Yet, it makes play a powerful tool for expressing freedom, as it challenges who has access to space, how it is used, and what behaviors become acceptable.

.

FOR PEOPLE who love surprises

TO SEE the hidden texture

IN unfamiliar streets

Chapter 3

FOR PEOPLE who speak many languages

TO SEE the stories in gestures

IN shadowed corners

This chapter will explore how play and attentive observation can foster connection and act as a form of productive resistance. It explores how transforming play into a collective experience creates space for new interactions and challenges isolation. I will reflect how my publications encourage engagement and connection, using playful and interactive elements to bring people together.

Do you ever wonder how many stories are hidden in gestures? They reside in hands that care, nurture, and show support. In hands that comfort, long for, and communicate between words.

Observing gestures, I learned about a Norwegian family that places their hands above their heads in a shape resembling a tipi to express comfort and satisfaction.

I discovered the story of two Italian sisters—the older one always pats the younger on the head to remind her that, to her, she will always be a child.

I learned about the Greek gesture called "mantza"—you show it with an open palm in irritation or frustration when you want someone to disappear from your sight.

I found out how someone noticed that bus drivers greet each other with a single hand gesture.

I remember many neighborly gestures from the place just outside Warsaw where I grew up. These small gestures reflected our relationships with our neighbors…On our street, everyone knew each other—we always greeted one another with a wave or a nod. We constantly borrowed flour or eggs from the neighbors across the street. Next to us lived a family with two daughters younger than me. When I outgrew my clothes, I passed them down to the younger girls on the other side of the fence. These small acts of kindness and sharing were a valuable part of our everyday neighborly life. Now, I’m trying to carry this memory from Warsaw to Rotterdam. I want that feeling of connection to settle in again—not just as a memory, but as something tangible.

I wonder how small gestures can be transformed into a publication? What happens when a publication is not meant to be kept, but to be shared? What if a publication was passed on through a handshake? Or was so wide that it would take two people to lift and open it? What if it disappeared after being read? Or only made sense when shared with others? What if it was worn and borrowed, but never owned? What if it had to be whispered to someone else, or had to be listened to rather than read? Can small gestures carry that little seed of connection within them?

I prepared a meeting, a performative dinner, to gather people around one table to collectively read a publication that is meant to be read by being shared. This dinner was an experiment in how small gestures can be translated into a publication that requires interaction with people. What happens when a publication is not meant to be kept but to be shared?

Everyone was served only a fragment of the text. In order to read the whole story, we had to share the parts we received. Everyone received a hint prompting them to share their fragment of the story in a publication that requires small interaction. Some where asked to be whispered, read by two people or passed through a handshake. By reading in this way, we uncovered the whole story. The goal was to turn reading into a shared act- an exchange, a physical connection.

What did we gain from this collective experience? The gathering I organized was meant to create a space for being together and collectively reading a text. Dinner of Gestures became a field for collective thinking. Play was an important part of this meeting, as it fostered imagination.There were no strictly defined rules, hints were not instructions but invitations to create publications that require interaction, contact, or exchange. Gathered around one table we could spin fantasies - about other forms of exchange. Through play, we moved beyond the usual ways of conversing and behaving.

We need connection and collective experience as a response to alienation in contemporary life. We need the perspective of others and different forms of interaction. The authors of Script for a Synthetic Play highlight the importance of the senses and performativity in challenging conventional modes of communication. In the introduction, they ask, “Can we have a conversation on the move? Can that conversation be creative and playful?” (Reznik, p.6), emphasizing the need for new approaches to create connections.

The book emerges from the performative symposium Unknown Grounds. The conversations that took place during this meeting were presented as fictionalized play. By incorporating performance and play, guests were invited to participate in more embodied ways of sharing knowledge, critically examining, questioning, and challenging the ways in which public life is shaped. Weaving fiction and role-playing became a way to reimagine collective participation.

“What’s unknown can seem strange and awkard. We shall welcome the perspective of the stranger, the newcomer, the outsider who doesn’t speak the language correctly, as we shall recognize the stranger in ourselves. We must practice strange way of dealing with questions, strange ways of conversating, and even stranger ways of behaving and sensing our environment” (Reznik, p. 6)

It is a call for unusual ways of exploring, questioning, and interacting with our surroundings. It is, in fact, a call for play. This strangeness becomes a tool for expanding our understanding of the world beyond our usual habits. Through play, we question what we normally take for granted.

Following this idea, play can be a tool for questioning and creating new possibilities. Play matters. In the book of this very title, Sicart suggests that play is a way of interacting with the world and making sense of it. The form of engagement that play allows, completely different from passive consumption, is, according to Sicart, something worth reflecting on (Sicart, page 5). When we play, instead of passively absorbing ideas, we improvise, we react actively, thus participating in collective thinking. Last time in the movement class with Amparo Gonzalez Sola, we explored what happens when you slow down or pause for a moment. What does it generate within the group? This experiment was fascinating because with each pause, my awareness of the people around me grew. The moment of stillness felt like listening. We were no longer just a mass of moving bodies, we were engaged in a dialogue. We were asked to take a pose, and then the next person would approach and, without touching, embrace our shape with their body, registering the form of our figure. After stepping out of this frame, a trace of your movement remained in the space. It was beautiful, like living sculptures. No one rushed in this playful exercise. The moment of slowing down created an opportunity to connect with the other person, giving time to look around and observe the frame they were forming around your figure. It was a continuous spatial dialogue. And perhaps it even awakened a greater attentiveness to others, to notice their rhythm and respond to it. And so, when the music stopped, we carried that shared rhythm within our bodies, observing one another to find a common melody in small gestures. I mention this example to say that stopping in space also enabled “conversing”. Play creates opportunities for this dialogue to happen. Dialogue that challenge isolation.

Perhaps when we become aware of the habits we navigate, stopping and participating in shared play provides a chance to move beyond the usual way of behaving. By adopting other ways of interacting with our environment we can foster new ways of relating, thinking, and being together.

.

FOR PEOPLE

TO SEE the city as a game

IN the most familiar places

Bibliography