User:Lbattich/Interview: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

''''' | '''''Please tell me what are you working on at the moment.''''' | ||

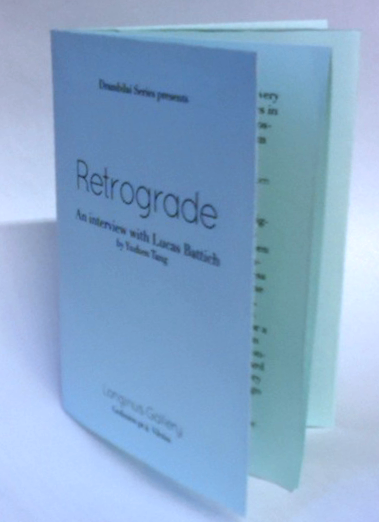

I’ve been working on a few different things. One of them includes practices of appropriating works from the past. I made a series of small artists’ chapbooks, titled Retrograde Chapbooks which reproduce manifestoes from the early twentieth-century avant-garde – Futurists and Dadaists manifestoes. For these chapbooks I changed them so that each sentence of the original texts would be in a backward order – so the first sentence would be now the last one, the second sentence would be the one before last. You would read it in a reverse mode, so to speak. | I’ve been working on a few different things. One of them includes practices of appropriating works from the past. I made a series of small artists’ chapbooks, titled ''Retrograde Chapbooks'' which reproduce manifestoes from the early twentieth-century avant-garde – Futurists and Dadaists manifestoes. For these chapbooks I changed them so that each sentence of the original texts would be in a backward order – so the first sentence would be now the last one, the second sentence would be the one before last. You would read it in a reverse mode, so to speak. | ||

The series has three publications at the moment, each devoted to a particular text. I started with the Futurist manifesto, because it was one of the most influential texts of the avant-garde, and it has been considered during the twentieth century like a template of art manifestoes. The series continues with other influential manifestoes after this. The intention with this series is to propose a “going-back” movement of sorts, which is a very literally movement, by putting all sentences in a different order. I see the series as proposing to travel back to an idea of modernism that we don’t have anymore. | The series has three publications at the moment, each devoted to a particular text. I started with the Futurist manifesto, because it was one of the most influential texts of the avant-garde, and it has been considered during the twentieth century like a template of art manifestoes. The series continues with other influential manifestoes after this. The intention with this series is to propose a “going-back” movement of sorts, which is a very literally movement, by putting all sentences in a different order. I see the series as proposing to travel back to an idea of modernism that we don’t have anymore. | ||

'''''What do you want the audience to get from | '''''What do you want the audience to get from these altered manifestoes?''''' | ||

This intervention does not change the original texts so much. A Dada manifesto still reads very much like a Dada manifesto even when the sentences are reversed. What interests me, and what I would like to express to the audience, does not reside only in the experience of reading these texts. | This intervention does not change the original texts so much. A Dada manifesto still reads very much like a Dada manifesto even when the sentences are reversed. What interests me, and what I would like to express to the audience, does not reside only in the experience of reading these texts. Instead, I aimed to embody a very nostalgic desire. The chapbooks function as a metaphor for a desire to go back to that time; a time when – as we like to imagine today – artists passionately believed in art’s progress, often toward a utopic end. In this sense the series is very nostalgic, because it points to a desire to go back in time, by going back with the text. | ||

Instead, I aimed to embody a very nostalgic desire. The chapbooks function as a metaphor for a desire to go back to that time; a time when – as we like to imagine today – artists passionately believed in art’s progress, often toward a utopic end. In this sense the series is very nostalgic, because it points to a desire to go back in time, by going back with the text. | |||

'''''I’m curious on what led you to make these appropriative works. Have you already worked with this content?''''' | '''''I’m curious on what led you to make these appropriative works. Have you already worked with this content?''''' | ||

I’ve always been interested in that time of history, particularly in Dada and the Russian avant-garde. I have previously worked in appropriating – perhaps “appropriating” is not a very good word; I prefer “quoting” or “repurposing” – other works by Dada artists, especially in relation to sound poetry. I made works by reimagining Hugo Ball’s and Raoul Hausmann’s sound poems, and Kurt Schwitters’ incredible sound epic, the Ursonate. My interest was in how these pioneering works function within our digital media age, as they are translated into binary code. I published books of the poems in their binary code versions, and also performed readings of these versions. | I’ve always been interested in that time of history, particularly in Dada and the Russian avant-garde. I have previously worked in appropriating – perhaps “appropriating” is not a very good word; I prefer “quoting” or “repurposing” – other works by Dada artists, especially in relation to sound poetry. I made works by reimagining Hugo Ball’s and Raoul Hausmann’s sound poems, and Kurt Schwitters’ incredible sound epic, the Ursonate. My interest was in how these pioneering works function within our digital media age, as they are translated into binary code. I published books of the poems in their binary code versions, and also performed readings of these versions. The ''Retrograde Chapbooks'', on the other hand, use a purely literary technique, by treating the original manifestoes as literary texts. | ||

The Retrograde Chapbooks, on the other hand, use a purely literary technique, by treating the original manifestoes as literary texts. | |||

'''''Would you say then that your sound poetry works in binary are more a visualisation of the sound, instead of literature?''''' | '''''Would you say then that your sound poetry works in binary are more a visualisation of the sound, instead of literature?''''' | ||

I think it depends on how you look at it. Part of the intention in turning the original sound poems into binary code is to show that in fact when you put anything into a computer it turns into binary. If you put Hugo Ball’s ''Karawane'' poem in a computer, or if you find it on the Internet, in a way it is already encoded and all we see is the surface – with my works I wanted to see what is behind. Even after being encoded, they are still textual, literary so to speak, and that’s why I want to read them as poems. But the works are as much about the visualisation as about the written words – because no one would read 400 pages of zeroes and ones. The publications are really visual objects, they are not something to read from cover to cover anymore. And perhaps that’s the interesting part: where do you say it is visual and where do you say it is literary? | |||

| Line 34: | Line 32: | ||

That’s true. Although perhaps if you train yourself very well you can understand binary encoding. Digital media, for all promise or potential of multi-mediality, is ultimately based on text, on a binary format which is addressed not to us, but to machines that can decode it. And without these machines the information stored in such format becomes redundant. | That’s true. Although perhaps if you train yourself very well you can understand binary encoding. Digital media, for all promise or potential of multi-mediality, is ultimately based on text, on a binary format which is addressed not to us, but to machines that can decode it. And without these machines the information stored in such format becomes redundant. | ||

Books, on the other hand, are usually seen as reliable storage devices, which perhaps last longer that the ephemeral content in the Internet. | Books, on the other hand, are usually seen as reliable storage devices, which perhaps last longer that the ephemeral content in the Internet. With sound poetry books I propose to preserve the original poems as they are found within digital media, keeping the irony that they are not addressed to humans anymore. | ||

''''' | '''''Can you expand on yout choice of books as an art form?''''' | ||

With the Retrograde Chapbooks it has been a deliberate choice, in the sense that I wanted to produce these works in the traditional literary chapbook format. Chapbooks would usually be limited editions very short publications of new poetry, very common in the literary world. The Futurist manifesto, for instance, appeared first in a newspaper, so the works are repurposing these texts in a different format. More generally, books – and these chapbooks as well – carry a measure of authority and durability, and that is something that I want to utilize in my works. | With the ''Retrograde Chapbooks'' it has been a deliberate choice, in the sense that I wanted to produce these works in the traditional literary chapbook format. Chapbooks would usually be limited editions very short publications of new poetry, very common in the literary world. The Futurist manifesto, for instance, appeared first in a newspaper, so the works are repurposing these texts in a different format. More generally, books – and these chapbooks as well – carry a measure of authority and durability, and that is something that I want to utilize in my works. | ||

''''' | '''''In light of these projects, how are you developing your future practice?''''' | ||

The Retrograde Chapbooks is an ongoing project. I am currently working on other texts to complement the series, and in a way compose a version of art history informed by the selected texts and the concept of a retrograde movement. | The ''Retrograde Chapbooks'' is an ongoing project. I am currently working on other texts to complement the series, and in a way compose a version of art history informed by the selected texts and the concept of a retrograde movement. | ||

Besides this project, at the moment I am continuing to work on and investigate the notion and use of colour in digital media, especially on the systemic division of colours into codes. | Besides this project, at the moment I am continuing to work on and investigate the notion and use of colour in digital media, especially on the systemic division of colours into codes. | ||

[[File:Interview-retrograde.png|Mini Booklet print]] | |||

Revision as of 21:12, 12 June 2015

Retrograde

An interview with Lucas Battich

By Yuzhen Chang

Please tell me what are you working on at the moment.

I’ve been working on a few different things. One of them includes practices of appropriating works from the past. I made a series of small artists’ chapbooks, titled Retrograde Chapbooks which reproduce manifestoes from the early twentieth-century avant-garde – Futurists and Dadaists manifestoes. For these chapbooks I changed them so that each sentence of the original texts would be in a backward order – so the first sentence would be now the last one, the second sentence would be the one before last. You would read it in a reverse mode, so to speak.

The series has three publications at the moment, each devoted to a particular text. I started with the Futurist manifesto, because it was one of the most influential texts of the avant-garde, and it has been considered during the twentieth century like a template of art manifestoes. The series continues with other influential manifestoes after this. The intention with this series is to propose a “going-back” movement of sorts, which is a very literally movement, by putting all sentences in a different order. I see the series as proposing to travel back to an idea of modernism that we don’t have anymore.

What do you want the audience to get from these altered manifestoes?

This intervention does not change the original texts so much. A Dada manifesto still reads very much like a Dada manifesto even when the sentences are reversed. What interests me, and what I would like to express to the audience, does not reside only in the experience of reading these texts. Instead, I aimed to embody a very nostalgic desire. The chapbooks function as a metaphor for a desire to go back to that time; a time when – as we like to imagine today – artists passionately believed in art’s progress, often toward a utopic end. In this sense the series is very nostalgic, because it points to a desire to go back in time, by going back with the text.

I’m curious on what led you to make these appropriative works. Have you already worked with this content?

I’ve always been interested in that time of history, particularly in Dada and the Russian avant-garde. I have previously worked in appropriating – perhaps “appropriating” is not a very good word; I prefer “quoting” or “repurposing” – other works by Dada artists, especially in relation to sound poetry. I made works by reimagining Hugo Ball’s and Raoul Hausmann’s sound poems, and Kurt Schwitters’ incredible sound epic, the Ursonate. My interest was in how these pioneering works function within our digital media age, as they are translated into binary code. I published books of the poems in their binary code versions, and also performed readings of these versions. The Retrograde Chapbooks, on the other hand, use a purely literary technique, by treating the original manifestoes as literary texts.

Would you say then that your sound poetry works in binary are more a visualisation of the sound, instead of literature?

I think it depends on how you look at it. Part of the intention in turning the original sound poems into binary code is to show that in fact when you put anything into a computer it turns into binary. If you put Hugo Ball’s Karawane poem in a computer, or if you find it on the Internet, in a way it is already encoded and all we see is the surface – with my works I wanted to see what is behind. Even after being encoded, they are still textual, literary so to speak, and that’s why I want to read them as poems. But the works are as much about the visualisation as about the written words – because no one would read 400 pages of zeroes and ones. The publications are really visual objects, they are not something to read from cover to cover anymore. And perhaps that’s the interesting part: where do you say it is visual and where do you say it is literary?

To the computer it makes sense, but not to humans.

That’s true. Although perhaps if you train yourself very well you can understand binary encoding. Digital media, for all promise or potential of multi-mediality, is ultimately based on text, on a binary format which is addressed not to us, but to machines that can decode it. And without these machines the information stored in such format becomes redundant.

Books, on the other hand, are usually seen as reliable storage devices, which perhaps last longer that the ephemeral content in the Internet. With sound poetry books I propose to preserve the original poems as they are found within digital media, keeping the irony that they are not addressed to humans anymore.

Can you expand on yout choice of books as an art form?

With the Retrograde Chapbooks it has been a deliberate choice, in the sense that I wanted to produce these works in the traditional literary chapbook format. Chapbooks would usually be limited editions very short publications of new poetry, very common in the literary world. The Futurist manifesto, for instance, appeared first in a newspaper, so the works are repurposing these texts in a different format. More generally, books – and these chapbooks as well – carry a measure of authority and durability, and that is something that I want to utilize in my works.

In light of these projects, how are you developing your future practice?

The Retrograde Chapbooks is an ongoing project. I am currently working on other texts to complement the series, and in a way compose a version of art history informed by the selected texts and the concept of a retrograde movement.

Besides this project, at the moment I am continuing to work on and investigate the notion and use of colour in digital media, especially on the systemic division of colours into codes.