User:Zuhui//notes/👀/Georges Perec's Thinking Machines: Difference between revisions

m (Zuhui moved page User:Zuhui/👀/Georges Perec's Thinking Machines to User:Zuhui/Notes/Georges Perec's Thinking Machines) |

|

(No difference)

| |

Revision as of 19:12, 6 January 2025

Semantic Poetry and P.A.L.F

The "Semantic Poetry" devised by Stefan Themerson is an experimental approach that deconstructs the meaning and essence of traditional poetry by replacing words in the poem with their dictionary definitions.

(take a line from William Wordsworth)

“I wandered lonely as a cloud…”

↓

“I wandered lonely as a mass of watery vapor suspended in the upper atmosphere”

이 과정에서, 원래 구절이 갖고 있던 시적 정서와 이미지가 상실되고, 대신 무미건조하고 기계적인 언어가 남게 된다. 테메르손의 이 기법은 두 가지 측면에서 독특하다:

1. 시의 정체성 해체: 의미 시는 독자가 시를 해석할 때 느끼는 직관적 아름다움과 감성을 의도적으로 제거해 버린다. 감성적이거나 상징적인 언어는 사전적 정의로 치환되며, 이는 시적 표현이 아닌 단순한 설명으로 바뀌어 시가 가진 본래의 매력을 빼앗는 것이다. 이를 통해 시가 단순히 언어적 구성 이상의 것이라는 점을 역설적으로 강조하는 셈. 2. 문학적 진정성에 대한 질문: 테메르손은 의미 시를 통해, 문학이나 시가 ‘진정한 의미’를 전달한다고 믿는 전통적 관점을 조롱한다. 그는 언어와 의미의 상관관계가 반드시 직관적이거나 감정적일 필요가 없으며, 문학이 본질적으로 무의미한 표현이 될 수도 있음을 보여준다.

P.A.L.F and exhausting the lexicon experiment

P.A.L.F. makes translation by semantic definition a recursive device (applying it over again to the output of the “machine”) and quickly produces monstrously inflated expressions that tend asymptotically toward the inclusion of all the words in the lexicon. Perec and Bénabou hypothesized that if any text subjected to the automatic production device tended toward the exhaustion of the lexicon, then any two texts would at some point of expansion come to include the same words as each other.

Technically it didn't work, but I like it. Like some kind of a philosophical jest suggesting that if all texts were infinitely expanded, they would ultimately converge to the same content in essence.

60s' Post-structuralism

P.A.L.F. is of interest as the first explicitly mechanical device entertained by Perec for the production of literary texts, and also as a symptom of the ‘60s’ fascination with the potential of the signifier to subvert, overturn, and generally wreak havoc with meaning and authorial intention.

1.기호의 전복적 잠재력:

기호가 단순히 의미를 전달하는 수단이 아니라, 의미를 바꾸고 뒤집고 혼란스럽게 만들 수 있는 잠재력을 가졌다고 본 시기. 기호 그 자체가 의미나 의도(authorial intention)를 쉽게 고정시킬 수 없는 힘을 가진다는 인식의 확산.

e.g. 한 단어가 특정 의미를 전달하려 하지만, 그 단어 자체가 다의성을 가지기 때문에, 의도와는 다른 해석이 생길 수 있다. 이런 점에서 1960년대 사상가들은 기호가 단일한 의미로 고정될 수 없다는 것을 발견하고, 기호의 이 혼란스러운 힘을 적극적으로 탐구했다. 2.저자 의도의 해체:

기호의 의미가 변함에 따라, 저자의 의도 역시 전복될 수 있다는 생각이 1960년대에 퍼지기 시작했다. 이는 포스트구조주의의 중요한 아이디어 중 하나로, 저자가 무언가를 의미했다고 해도, 독자가 그 기호를 어떻게 해석하느냐에 따라 의도와는 다른 의미가 생길 수 있다는 것. 따라서 텍스트는 독자의 해석에 따라 계속해서 재구성될 수 있는 존재가 되며, 저자의 의도는 점점 더 무의미해지거나 부차적인 것으로 간주됨. 3.P.A.L.F.와 기호 실험:

페렉의 P.A.L.F.는 기호가 가진 이러한 전복적 힘을 실험하는 장치이다. 이는 기계적으로 텍스트를 만들어내며, 단어와 기호를 반복적으로 정의하고 변환하면서 원래의 의도를 전복시키고, 최종적으로 텍스트에 대한 이해를 완전히 혼란스럽게 만드는 방식으로 작동하기 때문이다.

이를 통해 의미나 의도는 고정될 수 없고 무너질 수 있는 불안정한 것이라는 점을 실험하게 되는 것이며, 이는 1960년대의 언어와 기호에 대한 관심, 그리고 기호가 기존의 의미 체계를 전복하는 가능성을 잘 보여주는 예라고 할 수 있음.

Constraint

A constraint is any operation that can be made fully explicit on some level or another of a language (sound, letter, word, sentence…) and which gives rise to a new text. The first of Perec's Oulipian works to appear in French was his famous lipogram, A Void, a novel of three hundred pages written without the help of the letter e (the constraint being to write with only twenty-five letters, but within the grammar and lexis of the standard language nonetheless).

Algorithm and Death

Kafka machine

...But that would only lead to a conventional “Frankenstein” scenario, and Perec dropped the idea. He then turned to an entirely different use that might be made of an imaginary computer: to answer the question, What is poetry?

the most exciting work at that time concerned authorial attributions through the use of rival stylometric algorithms.

...

What attracted Oulipo's particular attention was the idea that if it was possible to identify authorship by algorithm, then the same algorithm might be used in reverse to produce a synthetic text that would be indistinguishable (for a computer) from authentic material.

-Today's AI

1.문체 분석 알고리즘: 문체 분석 알고리즘은 저자의 고유한 문체를 특정 수치나 변수(예: 단어 빈도, 평균 문장 길이 등)로 분석했다. 이를 통해 특정 텍스트가 특정 작가의 문체와 일치하는지 판별할 수 있으며 예를 들어, 어떤 텍스트가 단어 빈도나 문장 구조를 통해 ‘카프카’의 스타일과 유사한지를 따져볼 수 있게 된다. 2.역방향 적용: 여기서 울리포의 흥미로운 발상은 이 알고리즘을 역으로 사용하는 것이다. 즉, 카프카의 스타일 분석에서 추출한 변수들을 이용해 알고리즘이 직접 카프카와 유사한 스타일의 텍스트를 생성하도록 하는 것. 이렇게 만들어진 텍스트는, 특정 작가(이 경우 카프카)의 문체를 반영하므로 컴퓨터나 독자도 진짜와 구별하기 어려울 정도로 그 작가와 비슷한 문체를 갖추게 된다는 것이다. 3.카프카 기계: 이를 통해 만들어진 기계, 즉 “카프카 기계”는 카프카의 스타일을 모방하여 새로운 텍스트를 자동으로 생성하는 장치가 된다. 이 기계가 작동한다면, 실제로 카프카가 쓴 것이 아닌데도 그의 문체와 매우 비슷한, “카프카적”인 텍스트를 생성할 수 있게 되는 것이다. 이는 마치 카프카의 무의식적인 창작 과정을 기계가 재현해내는 것처럼 보이기 때문이다.

Die Maschine

But Die Maschine is not just a way of subverting Goethe. The last part of this sixty-minute play takes a different approach, and seeks the connections between this poem and the nature of poetry through analogous lines from the vast thesaurus of world poetry that the speaking computer naturally contains. The “explosion of quotations” of lines of verse in seven languages about nature, silence, and mortality produces a final movement that is the reverse of the play's aggressive number-crunching start. The verse tails off into the words for “silence” and “peace” repeated rhythmically in Japanese, Russian, English, Spanish, Italian, French, and German; a long “shhh…”; and then silence. In the end, something really has been said about what poetry is.

What enabled this to speak about poetry?

Because of the universality of themes that humans address in poetry?

Flow chart

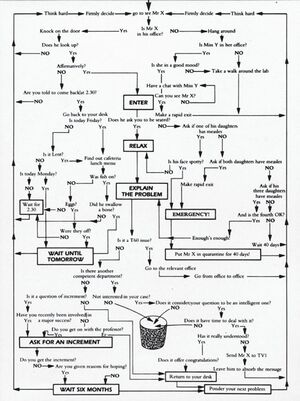

...“It consists of a certain number of propositions that can take either yes or no for an answer, each answer having certain consequences. The concatenation of causes and effects and the choice of answers are represented by arrows that are the only syntactic connectors between the propositions. In brief, it is a tree structure, a network, a labyrinth, and the “reader” chooses ONE route among all the possible routes, the totality of possible routes being presented SIMULTANEOUSLY on the flow-chart.”

A flowchart, as Perec explained to Helmle, shows simultaneously all the steps and the order of their recursion in a set of instructions. It also contains within it all the possible moves allowed by the algorithm. It is therefore an essentially Perecquian device, being at once exhaustive and simultaneous.

When put like this, it's such an interesting concept.

1. 플로차트의 "완전성"과 "동시성"

완전성(Exhaustiveness): 페렉의 플로차트는 주어진 절차에 따라 발생할 수 있는 모든 경로와 단계를 모두 포함하고 있다. 즉, 어떤 경우에도 빠뜨리지 않고 가능한 모든 행동의 선택지와 경로를 제시하는 구조인 것. 이는 페렉이 추구한 “소진(Exhaustion)” 개념과 맞닿아 있는데, 페렉의 문학적 기법은 특정 주제나 구조를 철저히 탐구하고, 다루고 있는 모든 요소를 빈틈없이 다루려는 시도를 포함하는 것이다. 이 플로차트는 그 본질을 잘 보여주고 있는 것. 동시성(Simultaneity): 플로차트는 단순히 순차적으로 단계가 진행되는 것이 아니라, 모든 단계가 동시에 펼쳐져 보여지면서 다양한 가능성을 한눈에 확인할 수 있게 한다. 이는 독자가 특정 상황에서 선택지를 보는 것이 아니라, 각기 다른 선택지가 동시에 존재한다는 점을 인식하게 만드는 것. 이러한 방식은 페렉이 강조한 “동시적 서사”와도 연관이 있다. 그는 다양한 사건과 인물이 동시에 발생하는 상황을 묘사하는 것을 즐겼고, 이를 통해 특정한 흐름이 아닌 여러 가능성을 복합적으로 보여주는 서사 방식을 만들어낸다.

i.e. “Life A User's Manual”, similarly an exhaustive description of all the rooms in the building at 11, rue Simon Crubellier, and a simultaneous account of all that is happening there toward eight in the evening on June 23, 1975…

2. 플로차트의 "재귀성과 무한 루프", 시간의 재삽입과 서사의 한계

플로차트에는 재귀성(recursiveness)이라는 중요한 특성이 존재한다. 재귀성이란 특정 조건에 따라 이전 단계로 되돌아가는 과정을 반복할 수 있는 구조를 의미하는데, 페렉의 플로차트는 사용자가 예/아니오 등의 선택에 따라 다시 상사의 사무실로 돌아가거나 처음부터 다시 시도하는 식으로 무한히 순환할 수 있는 구조를 가지고 있다.

알고리즘이 이론적으로 무한히 돌아갈 수 있는 구조를 가지고 있는 반면, 페렉은 이 서사를 쓸 때 시간이 자연스럽게 서사에 개입한다는 것을 발견하게 된다. 예를 들어, 급여 인상을 요청하는 직원이 상사를 만나러 갈 때마다 시간이 흐르고 그 사람은 나이를 먹어간다. 어떤 선택을 하고 다시 상사의 사무실로 돌아가는 과정이 수차례 반복되더라도, 각 시도마다 직원은 조금씩 나이가 들어가며 시간이 흐르는 것을 느낄 수밖에 없다. 결국, 알고리즘적 구조에서 벗어나지 않더라도 인간의 서사는 시간을 동반할 수밖에 없는 셈.

3. 페렉 문학에서의 "동시적 장치"로서의 플로차트

플로차트가 페렉 특유의 문학적 장치로 중요한 이유는, 그의 작품들이 동시에 여러 사건과 인물을 다루고, 각자의 선택이나 상황이 여러 가지 방식으로 변화할 수 있는 가능성을 제시한다는 점에 있다. 예를 들어, 그의 대표작 '인생 사용법'은 하나의 건물 안에 존재하는 다양한 방과 인물들을 동시에 서술하면서, 마치 독자가 건물의 여러 방을 한 번에 볼 수 있는 다중적 관찰자처럼 느끼게 한다.

이와 마찬가지로 플로차트는 하나의 흐름이 아닌, 다양한 가능성들이 동시에 펼쳐진다(즉, 모든 단계와 선택지가 열린 상태로 존재한다)는 점에서 페렉의 다층적이고 다각적인 서사 구조를 반영한다. 플로차트는 페렉이 추구했던 여러 서사적 가능성을 하나로 통합해 동시에 보여주는 형식적 장치인 것.

Clinamen

The theory of the clinamen, insofar as it relates to Perec's work, is that intentional irregularity softens the harshness of a text written under constraint, bringing all-too-human fallibility into the domain of formal art.

It's a way of having your cake and eating it too, for a clinamen is not an example of fallibility, but an intentional bending of self-imposed rules to show that the writer is in complete command not only of necessity, but also of chance.

Its secondary effect is perhaps even more important in the end: systematic non-respect of a systematic rule makes the rule unrecoverable from the finished text. = 규칙을 체계적으로 지키지 않음으로써 최종 텍스트에서 규칙을 추적할 수 없게 만든다는 점.

↘︎ 더 레이즈는 알고리즘의 절차를 어느 정도 따라가면서 듣는 이에게 불가피한 좌절감을 심어주지만, 그 규칙을 충분히 벗어나 예상되는 알고리즘적 구조를 파악할 수 없게 한다. 여섯 개의 목소리는 항상 논리적 절차에 따라 말하는 것이 아니고, 여섯 개의 요소가 한 번씩 순환하는 과정도 반드시 결말에 이르지는 않으며 , 로 표시된 일시 정지 또한 반드시 절차의 시작점으로 돌아가라는 의미는 아니다. 그래서 아무리 애써도 페렉의 알고리즘적 연극에서 실제 알고리즘을 추론할 수 없게 되는 결과를 만든다.

The Conceptual Background of Clinamen

Clinamen is a concept originating from the ideas of the ancient Greek philosopher Epicurus and the Roman poet Lucretius. Lucretius, from an atomistic perspective, described how all atoms fall in a straight line but sometimes deviate slightly, moving unexpectedly due to a “small swerve” (clinamen). He saw this swerve as creating opportunities for all things and phenomena to change freely, beyond predetermined laws or necessity.

클리나멘과 알고리즘적 구조의 관계

클리나멘은 알고리즘적 구조나 규칙의 존재를 부정하지는 않지만, 그 안에서 발생할 수 있는 편차나 오류, 예외를 자연스럽게 받아들인다. 따라서 클리나멘은 알고리즘을 완벽하게 따르지 않는 일종의 유연성을 지니며, 이는 알고리즘적 절차가 갖는 기계적 경직성을 인간적 관점에서 완화하는 방식으로 작용할 수 있다. 클리나멘은 규칙 내에서 발생하는 불가피한 일탈로, 이는 완전히 규칙을 위반하는 것이 아니라 규칙을 유지하면서도 규칙의 틀 안에서 자유로운 편차를 허용하는 개념이다.

클리나멘의 예시

리포그램(Lipogram)에서의 작은 일탈

리포그램은 특정 글자를 전혀 사용하지 않고 글을 쓰는 장르이다. 예를 들어, 조르주 페렉의 '사라진 남자(A Void)'는 ‘e’라는 글자를 전혀 쓰지 않고 300페이지에 달하는 소설을 쓴 예이다. 여기서의 규칙은 ‘e’를 쓰지 않는 것이지만, 이 규칙이 주는 한계를 극복하기 위해 페렉은 다양한 언어적 변주를 시도하게 됩니다. 즉, ‘e’를 피하기 위해 더 많은 단어를 설명하거나 표현을 우회하는 과정에서 의도치 않게 독특한 문체나 예상하지 못한 표현이 나오게 되죠. 이로 인해 발생하는 언어적 다양성은 클리나멘의 성격을 지니며, 규칙이 작품을 단조롭게 만드는 대신 작품의 창의성을 확장하게 만드는 요소로 작용합니다.

펠릭스 펜던의 100만 번째 시도와 같은 엄격한 숫자 규칙 속에서의 일탈

울리포의 다른 작품 중, 펠릭스 펜던의 100만 번째 시도는 엄격하게 숫자를 기반으로 쓰인 시이다. 이 작품은 정확히 100만 개의 글자로 이루어져야 한다는 규칙을 따르며, 글자 수를 맞추기 위해 일부 단어나 표현을 예상치 못하게 줄이거나 늘리는 변형이 생겨나게 된다. 이 과정에서 글자의 수를 맞추기 위해 문장의 일부가 생략되거나, 덧붙여지거나, 반복되기도 한다. 이는 일종의 필연적인 클리나멘으로 작용하며, 독자는 정해진 규칙 속에서 생기는 예상치 못한 리듬과 구조적 변형을 경험하게 되는 것.

하이쿠(俳句)에서 발생하는 예상치 못한 의미 변주

일본의 전통 시인 하이쿠는 5-7-5 음절의 엄격한 구조로 지어진다. 이 형식은 매우 제한적이기 때문에, 자연스럽게 단어 선택이 매우 절제되며 복합적인 의미를 갖게 되는 경우가 생긴다. 예를 들어, 어느 구절에 계절이나 감정이 한두 단어로 표현될 때, 독자는 그 짧은 문구 안에 함축된 여러 의미를 해석하게 된다. 이런 경우, 짧은 형식 안에서 예상치 못한 해석이나 감정이 발생하는데, 이는 하이쿠의 규칙 속에서도 필연적으로 발생하는 자연스러운 변주이자 클리나멘의 예로 볼 수 있음.

알고리즘적 구조에서의 일탈

예를 들어 페렉의 더 레이즈에서 사용된 알고리즘적 구조는 급여 인상을 요청하는 절차를 엄격하게 따라가는 형식이지만, 이야기 속에서 주인공이 상사를 기다리다 병을 얻거나, 상사가 새로운 인물로 교체되는 등의 외부 요인에 따른 예상치 못한 변화가 발생하게 된다. 이는 알고리즘이 허용하지 않는 예외이지만, 현실적인 설정을 반영하면서 알고리즘의 반복적 구조에 변화를 주는 역할을 한다. 이렇게 엄격한 규칙을 유지하면서도 일상적인 우연이 삽입되는 변주가 클리나멘으로 작용하는 것.

→클리나멘의 핵심: 규칙을 준수하면서 발생하는 창의적 예외

클리나멘의 핵심은 규칙을 깨지 않으면서도 그 규칙 안에서 의도치 않게 발생하는 작은 변화가 예술적 효과를 만들어낸다는 것이다. 이러한 변화는 규칙을 따르는 자발적인 일탈이자, 규칙이 작가나 독자에게 예상치 못한 창의성을 제공하는 순간.