User:Artemis gryllaki/Special Issue 7: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 155: | Line 155: | ||

The text consists of ten theses, the first of which is a selection of criteria that allow us to test whether something is a Life Hack or not. The remaining theses present extended arguments supported by examples, on how to identify specific features of Life Hacks, in which environment (and space) they exist and what kind of culture they foster.<br><br> | The text consists of ten theses, the first of which is a selection of criteria that allow us to test whether something is a Life Hack or not. The remaining theses present extended arguments supported by examples, on how to identify specific features of Life Hacks, in which environment (and space) they exist and what kind of culture they foster.<br><br> | ||

Understanding Life Hacks in the context of an advanced capitalist society raises the question of the ambiguity of a system in which the entrepreneurial routine of the self is internalized to perform an ever-working life. In actuality, Life Hacks bring about the possibility of reappropriating everyday life in a creative and practical response, managing precarity and complexity.<br><br> | Understanding Life Hacks in the context of an advanced capitalist society raises the question of the ambiguity of a system in which the entrepreneurial routine of the self is internalized to perform an ever-working life. In actuality, Life Hacks bring about the possibility of reappropriating everyday life in a creative and practical response, managing precarity and complexity.<br><br> | ||

This publication includes a Life Hack in its format. With the addition of a series of holes, each loose page can be seen as a “hackable surface”. The publication aims to depart from the traditional form of a finished book, inviting readers to bind it using an eclectic choice from a range of unorthodox materials included with the publication. This strategy incentives the reader to rethink their personal ideal form of the book, transforming it into a hand-made object. As such, the publication is completed by the reader, who is left to improvise a make-shift solution to bind the publication. The goal is not only to share the text, but to also provide an experience in which a life-hacked binding transforms the reader into an active subject, rather than a passive consumer. This small conceit illustrates that the process is even more noticeable than the outcome.<br | This publication includes a Life Hack in its format. With the addition of a series of holes, each loose page can be seen as a “hackable surface”. The publication aims to depart from the traditional form of a finished book, inviting readers to bind it using an eclectic choice from a range of unorthodox materials included with the publication. This strategy incentives the reader to rethink their personal ideal form of the book, transforming it into a hand-made object. As such, the publication is completed by the reader, who is left to improvise a make-shift solution to bind the publication. The goal is not only to share the text, but to also provide an experience in which a life-hacked binding transforms the reader into an active subject, rather than a passive consumer. This small conceit illustrates that the process is even more noticeable than the outcome.<br</div> | ||

<div style='text-align: center; font-family: "Arial Narrow", Arial, sans-serif;font-size: 17px; margin: 20px; padding: 10px;'> | <div style='text-align: center; font-family: "Arial Narrow", Arial, sans-serif;font-size: 17px; margin: 20px; padding: 10px;'> | ||

Revision as of 09:43, 10 September 2019

Start up, Burn out: Life Hacks

Theoretical Framework ~Concepts, Themes, Readings~

| Burn Out | Life Hacks | Entrepreneurship | Entreprecariat | ||||||||||

| Precarity | Productiviy | Procrastination | Efficiency | Insecurity | |||||||||

| Flexibility | Labour Rights | Security | Gig Economy | 9-5 | |||||||||

| Alexa | Optimisation | Life Coach | Positive Affirmations | Ever-Working | |||||||||

| Eliza | Hackivism | Hackerspace | Artificial Intelligence | Get Things Done | Siri |

The entreprecariat is the semi-young creative worker who put effort in her own studio while freelancing for Foodora, the manager on the verge of a burnout, the employee who needs to reinvent himself as soon as his short-term contract is over, the fresh graduate who struggles to repay his loan with a top-notch university. As Guy Standing maintains, "the precariat consists of those who feel their lives and identities are made up of disjointed bits, in which they cannot construct a desirable narrative or build a career, combining forms of work and labour, play and leisure in a sustainable way."

Entreprecariats share the urgency to optimize their time, their mind, their body, and their soul in order to deal with precarious conditions, be they financial, psychological, affective, physiological, temporal, geographical. Lifehacker.com well represents this urgency, since it offers optimization techniques encompassing everything, from the work sphere to life as a whole. In the entreprecarious society, everyone is an entrepreneur and nobody is stable.

In his youth, Joseph Schumpeter, an influential Viennese economist, considered entrepreneurs to be a rare species that stands at the top of the social pyramid because of its precious ability to innovate. Starting from similar premises, management guru Peter Drucker argued that to accelerate innovation, society as a whole would have to become entrepreneurial, getting rid of that disincentive to progress that is the permanent job. Drucker’s vision is today a reality: in the face of widespread economic and employment insecurity, Schumpeter’s pyramid has been reversed. Everyone is called to free enterprise. This is the general sense of what we can call, with a dose of irony and bitterness, entreprecariat.

“Fake it till you make it” is an expression that embodies the existential crisis of the entreprecariat. Individuals become an incomplete product in constant optimization that resorts to a conspicuous optimism to present themselves as autonomous to others and to themselves. All this with the risk that, admittedly being the master of their own destiny, the responsibility for their own failures falls only on themselves.

Tachycardia

(60bpm) When you sit, keep your back straight

(65bpm) Then relax and eat your greens

(70bpm) That is it, you're doing great!

(75bpm) Measure your pulse, how is your rate?

(80bpm) Keep on working until it's dark

(85bpm) But break every forty minutes

(90bpm) Go for a jog out in the park

(95bpm) And don't forget to best your mark

(100bpm) Recycle, reuse and abuse

(105bpm) Your prescription for anxiety

(110bpm) Now don't make up an excuse

(115bpm) Finish all that cleansing juice

(120bpm) Leaving all your bills for last?

(125bpm) Your creditor will not approve...

(130bpm) With your ratings dropping fast

(135bpm) Bask in the glory of your past

(140bpm) Is this not set to explode?

(145bpm) Please please please, a helping hand

(150bpm) No credibility to erode?

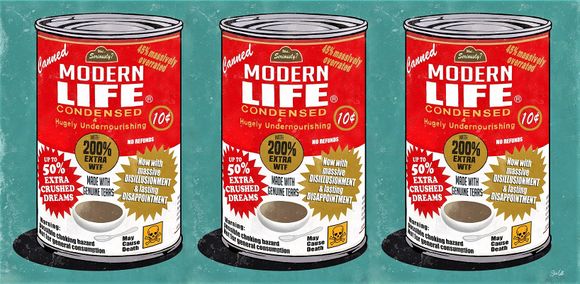

In Western society there is a drive to orient your thinking and behaviour on the objective of market success which dictates the private and professional spheres. Life is now ruled by competition for power, money, fitness, and youth. The self is driven to constantly improve, change and adapt to a society only capable of producing winners and losers.

The Entrepreneurial Self explores the series of juxtapositions within the self, created by this call for entrepreneurship. Whereas it can expose unknown potential, it also leads to over-challenging. It may strengthen self-confidence but it also exacerbates the feeling of powerlessness. It may set free creativity but it also generates unbounded anger.

Competition is driven by the promise that only the capable will reap success, but no amount of effort can remove the risk of failure. The individual has no choice but to balance out the contradiction between the hope of rising and the fear of decline. Ulrich Bröckling is Professor of Cultural Sociology at the Albert-Ludwigs-University Freiburg, Germany.

Read More: Ulrich Bröckling (2015). The Entrepreneurial Self : Fabricating a New Type of Subject. London: Sage Publications Ltd.

Entrepreneurial activity in his view, for instance, is not defined by risk taking. Neither does it involve scientific discoveries or inventing new technologies. Whereas “the inventor produces ideas,” Schumpeter asserts, “the entrepreneur ‘gets things done,’ which may but need not embody anything that is scientifically new.”

Entrepreneurs, he continues, are not managers and most often not owners of the means of production, only ones who have them at their disposal. The essence of entrepreneurship, instead, according to Schumpeter, is to create new combinations among already existing workers, ideas, technologies, resources, and machines. Entrepreneurs, in other words, create new machinic assemblages. Moreover, these assemblages must be dynamic over time. Whereas most capitalists merely pursue “adaptive responses to change,” adjusting their existing arrangements, entrepreneurs carry out “creative responses” that grasp and set in motion what is new in their world.

Read More: Schumpeter, J.A. (1947). The Creative Response in Economic History. The Journal of Economic History, 7(02), pp.149–159.

The relation between work, time and the more personal aspect of life is a focal point in Sennet’s book.

The state of today’s economy, described as “flexible capitalism”, has forced a constant rotation of jobs, cities, and friends which can be stimulating but can also contribute to an unstructured and meaningless life.

The author addresses these problems by analyzing his encounter with Rico, a successful man suffering from the uncertainty of life and the lack of longstanding values in society.

Read More: Sennett, R. (1999). The corrosion of character : the personal consequences of work in the new capitalism. New York: Norton.

Richard Florida identifies the emergence of a new social class that is reshaping the twenty-first century's economy, geography, and workplace.

This Creative Class is made up of people - engineers, managers, academics, musicians, researchers, designers, entrepreneurs, lawyers, poets and programmers - whose work turns on the creation of new forms. Increasingly, this Creative Class determines how workplaces are organized, what companies prosper or go bankrupt, and which cities thrive.

The “clustering force” of young creatives and tech workers in metropolitan areas was leading to greater economic prosperity. Don’t waste money on stadiums and concert halls, or luring big companies with tax breaks, Florida told the world’s mayors. Instead make your town a place where hipsters want to be, with a vibrant arts and music scene and a lively cafe culture. Embrace the “three T’s” of technology, talent and tolerance and the “creative class” will come flocking...

Read More: Florida, R. (2014). The rise of the creative class revisited. New York: Basic Books.

Software creates new spatialities in everyday life, from supermarket checkout lines to airline flight paths. After little more than half a century since its initial development, computer code is extensively and intimately woven into the fabric of our everyday lives. From the digital alarm clock that wakes us to the air traffic control system that guides our plane in for a landing, software is shaping our world: it creates new ways of undertaking tasks, speeds up and automates existing practices, transforms social and economic relations, and offers new forms of cultural activity, personal empowerment, and modes of play. In Code/Space, Rob Kitchin and Martin Dodge examine software from a spatial perspective, analyzing the dyadic relationship of software and space.

Read More: Kitchin, R. and Dodge, M. (2014). Code/Space : software and everyday life. Cambridge, Mass. [U.A.] Mit Press.

Under the praised work of the capitalist entrepreneur, lies the constant expropriation of the cooperative power of the multitude. The entrepreneurial function does not belong to a manager or a guru. On the contrary, it is accomplished through cooperation. As the main actors of the production process, the workers collaborate, while limiting their individuality and thus create social wealth.

Hardt and Negri introduce the novel term of “entrepreneurship of the multitude”. In the postmodern global economy, the production process is progressively based in new networks of collaboration and communication, in coordination with contemporary technologies. On these terms, the labor gradually acquires a degree of autonomy in production.

The “multitude” has the potential to reject the current social system as we know it and build novel forms of cooperation. Ultimately, the triumph of private property will be abandoned. In its place, the “autonomous organization of social cooperation” can build the ground where “social wealth is shared in common”.

Read More: Hardt, M. and Negri, A. (2017). Assembly. New York, Ny: Oxford University Press.

Ten Thesis On Life Hacks

~Collective Writing & Publishing Streams~

From Wikipedia: Etherpad (previously known as EtherPad) is an open-source, web-based collaborative real-time editor, allowing authors to simultaneously edit a text document, and see all of the participants' edits in real-time, with the ability to display each author's text in their own color. There is also a chat box in the sidebar to allow meta communication.

Ten Theses on Life Hacks is the first publication of Special Issue #07. It attempts to acquire a widened perspective on how Life Hacks can be defined and how they relate to our collective experiences and reflections.

Life Hacks are small improvisational interventions to the immediate environment; spontaneous actions that aim to improve or adapt materials to specific needs. A simple example, such as tying a knot in a earphone cable to determine easily which is for the left ear or the right without having to look, can be considered a Life Hack. They are diasporic, shared within communities both on- and offline in ever-increasing processes of self-optimisation.

The text consists of ten theses, the first of which is a selection of criteria that allow us to test whether something is a Life Hack or not. The remaining theses present extended arguments supported by examples, on how to identify specific features of Life Hacks, in which environment (and space) they exist and what kind of culture they foster.

Understanding Life Hacks in the context of an advanced capitalist society raises the question of the ambiguity of a system in which the entrepreneurial routine of the self is internalized to perform an ever-working life. In actuality, Life Hacks bring about the possibility of reappropriating everyday life in a creative and practical response, managing precarity and complexity.

INVENTORY OF MATERIALS AND PROCESSES

Recycled kraft board

Paper (200gsm)

Cling wrap

Sticker label

Disused polystyrene food packaging trays

A wide range of unorthodox binding materials (e.g. paperclips, carabiners, rubber bands, nuts and bolts, earrings etc.)

PUBLICATION LAUNCH

Launched at Varia, the Centre for Everyday Technology (Rotterdam) on 31.10.18 as part of the event “Life Hacks: Space”, including guests; author and designer Françoué Giraremeunier, the WORKNOT! collective (Arvand Pourabbasi and Golnar Abbasi), Varia, the Centre for Everyday Technology (represented by Roel Roscam Abbing, Manetta Berends and Niek Hilkmann). The Life Hacks series is curated by Silvio Lorusso, and jointly organized by Het Nieuwe Instituut’s Research Department and XPUB.