Eleanorg/thesis/consentInOnlineSystems: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| (5 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 11: | Line 11: | ||

:: If consent is a communicative act, which signifiers can be understood as giving consent? | :: If consent is a communicative act, which signifiers can be understood as giving consent? | ||

How the grammar, ontology and signification of consent are understood are political questions. For example: feminists campaigning against sexual violence will stress that consent must be a communicative act, not merely a state of mind. They are also likely to propose certain acceptable signifiers ('Yes means yes'), while discrediting others. And some even question the grammar outlined by Kleinig, arguing that a view of consent in which it is 'sought' and 'given' encodes unequal and polarized (gendered) subject positions.(find examples). | How the grammar, ontology and signification of consent are understood are political questions. For example: feminists campaigning against sexual violence will stress that consent must be a communicative act, not merely a state of mind ('Yes means yes' vs 'she wanted it'). They are also likely to propose certain acceptable signifiers ('Yes means yes'), while discrediting others. And some even question the grammar outlined by Kleinig, arguing that a view of consent in which it is 'sought' and 'given' encodes unequal and polarized (gendered) subject positions.(find examples). | ||

Thus, it is an interesting exercise to examine which 'flavours' are chosen for each of these three attributes by various organizations or pieces of software, and how these are then encoded technologically/socially. | Thus, it is an interesting exercise to examine which 'flavours' are chosen for each of these three attributes by various organizations or pieces of software, and how these are then encoded technologically/socially. | ||

| Line 19: | Line 19: | ||

Wikipedia articles may be edited by many users, with the aim of arriving at a consensus on the text. | Wikipedia articles may be edited by many users, with the aim of arriving at a consensus on the text. | ||

'''What is Wikipedia's grammar of consent?''' In Kleinig's terms, consent is given by A to B, for P. Here, P is any change to the text. B is the editor making the change. She seeks the consent of (plural) A, all other users. Wikipedia's grammar of consent thus conforms to a fairly conservative one in which consent is 'sought' and 'given' (challenged by feminists such as Millar (2008) and Kramer Bussel (2008)). However, it begins to stretch this grammar, as multiple users make proposals in an ongoing and collaborative process. A does not merely play the passive role of saying 'yes' or 'no', but is expected to be an active agent contributing her own changes if she disagrees. This expectation of agency informs how consent is signified. | '''What is Wikipedia's grammar of consent?''' In Kleinig's terms, consent is given by A to B, for P. Here, P is any change to the text. B is the editor making the change. She seeks the consent of (plural) A, all other users. Wikipedia's grammar of consent thus conforms to a fairly conservative one in which consent is 'sought' and 'given' (challenged by feminists such as Millar (2008) and Kramer Bussel (2008)). However, it begins to stretch this grammar, as multiple users make proposals in an ongoing and collaborative process. A does not merely play the passive role of saying 'yes' or 'no', but is expected to be an active agent contributing her own changes if she disagrees. It is unclear whether A includes readers of Wikipedia who do not have an account on the site. Are they, by reading the text and not creating an account in order to change it, consenting to the status quo? This expectation of agency informs how consent is signified. | ||

'''How is consent signified?''' In its policy on consensus, Wikipedia (2013a) states clearly that: "Any edit that is not disputed or reverted by another editor can be assumed to have consensus." A related essay linked from this statement, "Silence and Consensus" (Wikipedia Editors, 2013b) - though not a policy document - comments that "Consensus can be presumed to exist until voiced disagreement becomes evident... [because] In wiki-editing, it is difficult to get positive affirmation for your edits..." (ibid). Kleinig himself notes that signifiers are culturally-specific, and may include silence in some cases (Kleinig 2010, p.11). Because of this, "there must be a convention whereby consent given is recognized as such" (ibid). Wikipedia's policy on Consensus attempts to set in place this convention. However, this convention is not without controversy. The Wikipedia Essay "Silence Means Nothing" gives several examples of things that silence may signify ''other'' than consent: "polite disagreement", not having seen, or choosing to ignore an edit (Wikipedia Editors 2013c). | '''How is consent signified?''' In its policy on consensus, Wikipedia (2013a) states clearly that: "Any edit that is not disputed or reverted by another editor can be assumed to have consensus." A related essay linked from this statement, "Silence and Consensus" (Wikipedia Editors, 2013b) - though not a policy document - comments that "Consensus can be presumed to exist until voiced disagreement becomes evident... [because] In wiki-editing, it is difficult to get positive affirmation for your edits..." (ibid). Kleinig himself notes that signifiers are culturally-specific, and may include silence in some cases (Kleinig 2010, p.11). Because of this, "there must be a convention whereby consent given is recognized as such" (ibid). Wikipedia's policy on Consensus attempts to set in place this convention. However, this convention is not without controversy. The Wikipedia Essay "Silence Means Nothing" gives several examples of things that silence may signify ''other'' than consent: "polite disagreement", not having seen, or choosing to ignore an edit (Wikipedia Editors 2013c). | ||

| Line 37: | Line 37: | ||

==eConsensus== | ==eConsensus== | ||

<div style="float:left;"> | <div style="float:left;"> | ||

[[File:eConsensusMetaDataOptions.png]]</div> EConsensus.org is a relatively new online tool to help activists organize. Within 'groups', group members can create and comment upon 'proposals' as well as creating 'decisions'. | [[File:eConsensusMetaDataOptions.png]]</div> EConsensus.org is a relatively new online tool to help activists organize. Within 'groups', group members can create and comment upon 'proposals' as well as creating 'decisions'. The image to the left shows the commenting options which are displayed next to each proposal. The current totals for each type of comment are shown. Clicking on one creates a new comment with that tag [1]. | ||

'''What is its grammar of consent?''' What is being consented ''to'' is clear on eConsensus.org - proposals are named as such and given a unique ID. Proposals are commented on, and ultimately consented to (or not) by group members, whose name is registered next to their consent (if given). | '''What is its grammar of consent?''' What is being consented ''to'' is clear on eConsensus.org - proposals are named as such and given a unique ID. Proposals are commented on, and ultimately consented to (or not) by group members, whose name is registered next to their consent (if given). It attempts to mimic face-to-face consensus decision-making used in activist groups, in which a proposal is presented, discussed, modified and ultimately consented to by all involved. It is notable that each proposal may be modified at any time - possibly creating confusion as to which version of the proposal the comments (and consent) below refer to. | ||

'''What is the ontology of consent?''' Group users may comment upon proposals, and 'tag' their comment with only one option from this list: 'Question', 'Danger', 'Concerns', 'Consent', or merely 'Comment'. Consent must therefore be ''communicated'' as a clear gesture; writing a positive comment without tagging it as 'Consent' does not constitute consent. (Although users of the software may, of course, choose to implement their own conventions.) | |||

<div style="float:left;"> | |||

[[File:eConsensusMetaDataOptionsDropdown.png]]</div>'''How is consent signified?'''Consent is signalled by selecting 'Consent' from a dropdown list of tags (called 'ratings') when writing a comment on a proposal. The visual language used to display these tags is blunt. Comments tagged as 'Danger' have a red mark; comments tagged 'Consent' are bright green. 'Concerns' are orange, and sit in between Danger and Consent in the interface, creating a symbolic colour spectrum. (These are the very same colours that Doodle uses to encode 'yes', 'no' and 'maybe'.) Unlike Doodle, eConsensus lets users decide how to tag their responses, rather than giving initiators the power to decide whether or not users will be able to express ambivalance ('Ifneedbe' in Doodle; 'Concern' in eConsensus). | |||

It is interesting to note that it is not possible to give consent ''and'' signal danger or concern in the same comment. 'Comment' and 'Question' sit at either end of this spectrum, apparently unrelated to the middle three options in their respective shades of grey and blue. There is no option to refuse consent, ie 'block' a proposal, as there is in conventional face-to-face consensus. The assumption in the system must therefore be that proposals are never final, and are open to modification as long as concerns or dangers persist. It is notable that eConsensus (unlike Doodle) makes it technically impossible to refuse consent. It takes the Wikipedia approach of assuming that a rejection of the current proposal should be expressed as a modification, not a refusal. | |||

# Though as of 29 January 2013 this feature was broken, and users had manually to change the tag from its default setting, 'Comment'. | |||

Latest revision as of 11:24, 28 February 2013

How consent is understood & encoded in various online collaboration systems.

Today I'm going to look at how consent is understood and encoded in three systems for online collaboration: Wikipedia, e-consensus, and Doodle. While designed for varied use-cases, what these systems have in common is that they accept input from various users, and allow users to co-ordinate that input by offering various ways of establishing consensus.

In order to examine how 'consent' is understood in these systems, I'll use a theory of consent outlined by legal theorist Kleinig (2010) in his essay "The Nature of Consent". This essay offers a useful framework in which consent has (among others), the following three components:

- The grammar of consent.

- Who is involved, and how they interact. (Kleinig favours the following grammar: 'A consented (to B) to P.' P is the proposed action, B seeks consent, and A gives it.)

- The ontology of consent

- Is consent a state of mind, or must it be an action? (Kleinig argues for the latter (ibid p.10).

- Signification

- If consent is a communicative act, which signifiers can be understood as giving consent?

How the grammar, ontology and signification of consent are understood are political questions. For example: feminists campaigning against sexual violence will stress that consent must be a communicative act, not merely a state of mind ('Yes means yes' vs 'she wanted it'). They are also likely to propose certain acceptable signifiers ('Yes means yes'), while discrediting others. And some even question the grammar outlined by Kleinig, arguing that a view of consent in which it is 'sought' and 'given' encodes unequal and polarized (gendered) subject positions.(find examples).

Thus, it is an interesting exercise to examine which 'flavours' are chosen for each of these three attributes by various organizations or pieces of software, and how these are then encoded technologically/socially.

Wikipedia

Wikipedia articles may be edited by many users, with the aim of arriving at a consensus on the text.

What is Wikipedia's grammar of consent? In Kleinig's terms, consent is given by A to B, for P. Here, P is any change to the text. B is the editor making the change. She seeks the consent of (plural) A, all other users. Wikipedia's grammar of consent thus conforms to a fairly conservative one in which consent is 'sought' and 'given' (challenged by feminists such as Millar (2008) and Kramer Bussel (2008)). However, it begins to stretch this grammar, as multiple users make proposals in an ongoing and collaborative process. A does not merely play the passive role of saying 'yes' or 'no', but is expected to be an active agent contributing her own changes if she disagrees. It is unclear whether A includes readers of Wikipedia who do not have an account on the site. Are they, by reading the text and not creating an account in order to change it, consenting to the status quo? This expectation of agency informs how consent is signified.

How is consent signified? In its policy on consensus, Wikipedia (2013a) states clearly that: "Any edit that is not disputed or reverted by another editor can be assumed to have consensus." A related essay linked from this statement, "Silence and Consensus" (Wikipedia Editors, 2013b) - though not a policy document - comments that "Consensus can be presumed to exist until voiced disagreement becomes evident... [because] In wiki-editing, it is difficult to get positive affirmation for your edits..." (ibid). Kleinig himself notes that signifiers are culturally-specific, and may include silence in some cases (Kleinig 2010, p.11). Because of this, "there must be a convention whereby consent given is recognized as such" (ibid). Wikipedia's policy on Consensus attempts to set in place this convention. However, this convention is not without controversy. The Wikipedia Essay "Silence Means Nothing" gives several examples of things that silence may signify other than consent: "polite disagreement", not having seen, or choosing to ignore an edit (Wikipedia Editors 2013c).

What is the ontology of consent? Because consent in Wikipedia is signalled by silence, there is no clear distinction made between a state of mind, and the act of giving consent. Indeed, the only actions available to editors are ones which signal lack of consent. (Excepting perhaps the 'Wiki love' feature, whereby users express appreciation to other editors - although this isn't strictly a signal of consent.)

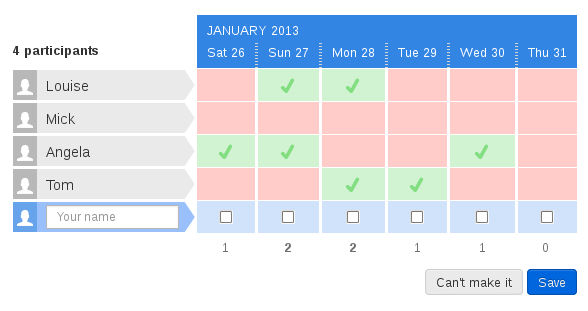

Doodle

Doodle lets anyone with the URL of a poll share their preferred days for a meeting, via a simple calendar 'polling' interface. Users of Doodle aren't consenting to anything per se - it is intended as an information-gathering tool to help a meeting planner chose the best date. However, it is an interesting example of the way that individual vs group preferences can be recorded and displayed. Its aim, like that of Wikipedia, is to arrive at a consensus - a date which may not suit everybody, but is the best of the possible options having taken group members' preferences into account.

What is its grammar of consent? In Doodle (unlike Wikipedia), in any given instance a proposal can only be made by one person, the poll initiator. The initiator chooses which dates to include in the poll, thus delimiting the choices presented. The single initiator therefore seeks the views of a number of other people. Only those who are 'invited', by being sent the poll URL, may participate in the poll. For each date, participants have by default only two choices: to check the box (meaning, I can make it), or to leave it unchecked (can't make it). Checked dates turn green, unchecked dates turn red. The poll initiator can enable, if they choose, a halfway option 'Ifneedbe', which when checked displays orange.

How is consent signified? For each date, users may check the box, or leave it blank. If no dates are suitable, the participant may save the form without checking any boxes, or click a button reading "Can't make it", which also submits the form blank. By implication, then, checking a box signifies "I can make it". A third, halway option ('Ifneedbe') may be enabled by the poll initiator. This signifies consent while registering reluctance. Any more detailed ambiguities must be recorded in a separate comments box below the poll, which is not semantically linked to it. The system narrows users' options in order to produce a clear numeric 'favourite'; thus the checked boxes can only be a rough guide, and not a reliable indication of felt preferences or desires.

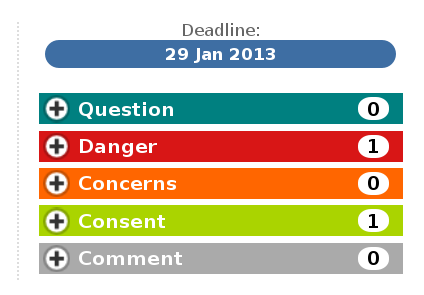

eConsensus

EConsensus.org is a relatively new online tool to help activists organize. Within 'groups', group members can create and comment upon 'proposals' as well as creating 'decisions'. The image to the left shows the commenting options which are displayed next to each proposal. The current totals for each type of comment are shown. Clicking on one creates a new comment with that tag [1].

What is its grammar of consent? What is being consented to is clear on eConsensus.org - proposals are named as such and given a unique ID. Proposals are commented on, and ultimately consented to (or not) by group members, whose name is registered next to their consent (if given). It attempts to mimic face-to-face consensus decision-making used in activist groups, in which a proposal is presented, discussed, modified and ultimately consented to by all involved. It is notable that each proposal may be modified at any time - possibly creating confusion as to which version of the proposal the comments (and consent) below refer to.

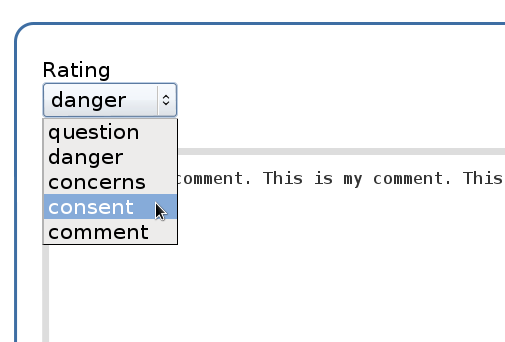

What is the ontology of consent? Group users may comment upon proposals, and 'tag' their comment with only one option from this list: 'Question', 'Danger', 'Concerns', 'Consent', or merely 'Comment'. Consent must therefore be communicated as a clear gesture; writing a positive comment without tagging it as 'Consent' does not constitute consent. (Although users of the software may, of course, choose to implement their own conventions.)

How is consent signified?Consent is signalled by selecting 'Consent' from a dropdown list of tags (called 'ratings') when writing a comment on a proposal. The visual language used to display these tags is blunt. Comments tagged as 'Danger' have a red mark; comments tagged 'Consent' are bright green. 'Concerns' are orange, and sit in between Danger and Consent in the interface, creating a symbolic colour spectrum. (These are the very same colours that Doodle uses to encode 'yes', 'no' and 'maybe'.) Unlike Doodle, eConsensus lets users decide how to tag their responses, rather than giving initiators the power to decide whether or not users will be able to express ambivalance ('Ifneedbe' in Doodle; 'Concern' in eConsensus).

It is interesting to note that it is not possible to give consent and signal danger or concern in the same comment. 'Comment' and 'Question' sit at either end of this spectrum, apparently unrelated to the middle three options in their respective shades of grey and blue. There is no option to refuse consent, ie 'block' a proposal, as there is in conventional face-to-face consensus. The assumption in the system must therefore be that proposals are never final, and are open to modification as long as concerns or dangers persist. It is notable that eConsensus (unlike Doodle) makes it technically impossible to refuse consent. It takes the Wikipedia approach of assuming that a rejection of the current proposal should be expressed as a modification, not a refusal.

- Though as of 29 January 2013 this feature was broken, and users had manually to change the tag from its default setting, 'Comment'.

- Millar, Thomas M. (2008) 'Towards a Performance Model of Sex', in Freidman, J. & Valenti, J. (eds) Yes Means Yes: Visions of Female Sexual Power and a World Without Rape (California: Seal Press).

- Kramer Bussel, R. (2008) 'Beyond Yes or No: Consent as Sexual Process', in Freidman, J. & Valenti, J. (eds) Yes Means Yes: Visions of Female Sexual Power and a World Without Rape (California: Seal Press).

- Wikipedia Editors (2013a) Wikipedia:Consensus [online]. Accessed 21 Jan 2013 at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wikipedia:Consensus.

- Wikipedia Editors (2013b) Wikipedia:Silence and Consensus [online]. Accessed 21 Jan 2013 athttp://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wikipedia:Silence_and_consensus

- Wikipedia Editors (2013c) Wikipedia:Silence Means Nothing [online]. Accessed 26 Jan 2013 at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wikipedia:Silence_means_nothing.