Cybernetics Workshop Plan: Difference between revisions

Dave Young (talk | contribs) |

Dave Young (talk | contribs) |

||

| (33 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

==Previous Version== | |||

A previous version of this plan can be found [http://pzwart3.wdka.hro.nl/mediawiki/index.php?title=Cybernetics_Workshop_Plan&oldid=34605 here]. | |||

==About== | ==About== | ||

I am currently planning a workshop that deals with the ''"cybernetic view of society"'' - essentially the post-World War II tendency to view society as a cybernetic entity whose behaviour can be managed and predicted through the use of mathematical systems. In my research last year, I proposed that this "cybernetic view of society" was an ideology born out of the complexity of Cold War politics, an attempt to regain some sense of control over the myriad of possible events that could tip the world into nuclear war. | I am currently planning a workshop that deals with the ''"cybernetic view of society"'' - essentially the post-World War II tendency to view society as a cybernetic entity whose behaviour can be managed and predicted through the use of mathematical systems. In my research last year, I proposed that this "cybernetic view of society" was an ideology born out of the complexity of Cold War politics, an attempt to regain some sense of control over the myriad of possible events that could tip the world into nuclear war. | ||

| Line 4: | Line 7: | ||

In Steve Rushton's lecture at the ''Masters of Reality'' launch, he spoke about how American was transitioning from a manufacturing-based economy to an information economy. With cybernetics provided the underlying logic to the management of this transition, cybernetics left the military domain and began to form an integral part of the workings of civil society itself. Cybernetic concepts were assimilated into management systems in corporations, municipal and governmental strategy, visual art/music/film/literature, environmental science, and the mass media's understanding of the world. The result was the formation of what Jack Burnham calls a ''"systems-oriented culture, where change emanates not from things, but from the way things are done."'' [http://www.arts.ucsb.edu/faculty/jevbratt/readings/burnham_se.html source] | In Steve Rushton's lecture at the ''Masters of Reality'' launch, he spoke about how American was transitioning from a manufacturing-based economy to an information economy. With cybernetics provided the underlying logic to the management of this transition, cybernetics left the military domain and began to form an integral part of the workings of civil society itself. Cybernetic concepts were assimilated into management systems in corporations, municipal and governmental strategy, visual art/music/film/literature, environmental science, and the mass media's understanding of the world. The result was the formation of what Jack Burnham calls a ''"systems-oriented culture, where change emanates not from things, but from the way things are done."'' [http://www.arts.ucsb.edu/faculty/jevbratt/readings/burnham_se.html source] | ||

The game [http://micropolisonline.com/ ''Micropolis''] (the open source version of Sim City) encapsulates these ideas in the form of an interactive game, in which the goal is to build a metropolitan utopia in an empty virtual landscape while trying to manage municipal finances, keep the population happy, and strike a balance between the division of labour in the city. The game presents the player with a simplified set of rules and some starting capital, and from then on he/she must decide how the city is to function without much further prompt from the game, other than basic feedback about crime rate or public opinion of tax rates, for example. The game presents the player with an exaggerated | The game [http://micropolisonline.com/ ''Micropolis''] (the open source version of ''Sim City'') encapsulates these ideas in the form of an interactive game, in which the goal is to build a metropolitan utopia in an empty virtual landscape while trying to manage municipal finances, keep the population happy, and strike a balance between the division of labour in the city. The game presents the player with a simplified set of rules and some starting capital, and from then on he/she must decide how the city is to function without much further prompt from the game, other than basic feedback about crime rate or public opinion of tax rates, for example. The game presents the player with an exaggerated cybernetic view of society: the rules of the game are mutually dependent, affecting each other through feedback loops, recursion, and cellular automata-like systems. The result is an impression of a city inhabited by people (referred to as ''Sims'') with jobs, homes, and opinions on how the city is being run. | ||

==Methodology== | |||

The workshop is presented as a social experiment, a study of how people organise themselves when making decisions as a group. They will be presented with the brief to build a city within the game Micropolis, but there are not enough computers for all people to play the game individually. From this point, the participants have to decide how to proceed. | |||

==Why Micropolis?== | |||

Micropolis provides a link between two eras of computer technology: the Cold War period of game theory, statistical models, and the desire to simulate and predict the actions of the masses; and the rise in popularity of of the "personal computer" in the 1980s. Micropolis softens the cybernetic ideology inherited from the Cold War period and presents it as a "game" - not in a Von Neumann sense, but in the as a source of entertainment. Despite this, there are a number of fictional or problematic truths hidden within the game's interface that communicates a form of politics: Nuclear power vs Coal; Crime vs class; the automatic provision of a welfare system; and the various inputs that affect the satisfaction rating of the population. Above all, the game requires the participant to view the simulated society as a systematic entity, which draws quite direct parallels to the era of Cold War computing and various projects funded by the US Military from the 1940s up to today. I feel that Micropolis presents a good interface to unpack these two strands as a group. | |||

Another reason I chose Micropolis is because of its history - it was one of the first popular city-building simulation computer games (designed to be played for entertainment), and has been adopted into the One Laptop Per Child project. The OLPC project is in many ways a product of the main aims of the countercultural ideology: democratising access to computer technology, and using it as an open educational platform. By participating in OLPC project, Micropolis remains a component of the belief that computers can somehow deliver a utopian society. | |||

My aim with this workshop is to open a debate with the participants about the | ==Outcomes== | ||

My aim with this workshop is to open a debate with the participants about the cybernetic view of society and systems-oriented culture in general. I am curious to hear how people feel we have gained from this transition, and how we might be adversely affected. I see the workshops as serving two purposes: firstly, they are an end in themselves - they are designed to encourage the participants to draw new conclusions about the systems that mediate our society, to question the necessity, and if/how they contribute to a better way of life. Secondly, I hope that the workshops can function as "field-research", and that I can use some of the ''feedback'' I receive from these workshops to inform my practice. I see great value in avoiding an insular and individualistic approach to my research this year: the formation of micro-communities for the duration of the workshops are integral to a practical understanding of my research. | |||

==Workshop Structure== | ==Workshop Structure== | ||

===Overview=== | ===Overview=== | ||

The workshop structure will operate best with 6-10 participants, and over the course of a | The workshop structure will operate best with 6-10 participants, and over the course of a 2-3 hour session split into 2 sections. The first section lasts approximately 1.5 hours, beginning with a brief introduction to the game ''Micropolis''. The participants then play the game either ''as a committee'' or individually (to be decided), making decisions together and trying to build a utopian metropolis. The final section takes the form of an open discussion about the first two sections of the workshop. Specifically, how the participants feel the lecture and the game relate to each other, and how both relate to their own experiences of 21st century society. | ||

The workshop would require the following facilities: | The workshop would require the following facilities: | ||

| Line 19: | Line 31: | ||

===Section 1=== | ===Section 1=== | ||

The second section of the game is centered around playing ''Micropolis''. At this point, I'm unsure of how to organise the group. There are a number of scenarios I can work with: | |||

====Scenario 1==== | |||

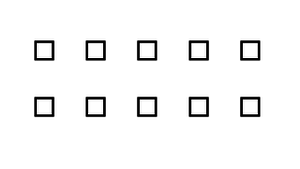

[[File:scenario-1.png | thumb | Scenario 1: Disconnected / Island]] | |||

Allow the participants to play individually using their own computers. This approach focuses on them managing the internal system of Micropolis, making their own decisions to construct their own idea of a fully-functional city. | |||

This approach follows a topology in which the nodes are independent of one another, and are not networked, as in the thumbnail image on the right. It is a non-social and autocratic model: each participant relies on their own skills to develop their city. | |||

This system can become dynamic if multiple participants decide to give each other advice. In this situation, a fluid mesh network may develop, and the participants will no longer be "islands", but can cause a social effect that will influence how they manage their individual cities. | |||

====Scenario 2==== | |||

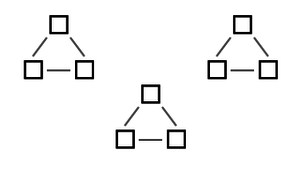

[[File:scenario-2.png | thumb | Scenario 2: Multiple Mini-Networks]] | |||

Ask the participants to form ''committees'' of 2-3 people and start playing the game. In this instance, the participants have to manage two systems - the internal system of the game, and also the social system constructed around them. They have to make decisions about how the city should be built as a group, providing each other with feedback about how they feel they should progress in the game. | |||

This topology takes the form of a group of mini-networks, within which the participants can make decisions and consult with other on how the game is to be played. There is no hierarchical bias built into the networks, but one may emerge through the course of playing the game. The participants can also decide how to delegate: they can assign particular tasks to each other, or propose a [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Time-sharing time-share] system, etc. | |||

====Scenario 3==== | |||

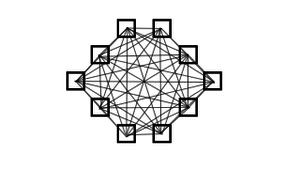

[[File:scenario-3.png | thumb | Scenario 3: Mesh Network]] | |||

Play the game as one group, so that all decisions must be made by a large committee. This will increase the variety of the social system, and may cause the decision-making process to become increasingly complex. I would give the participants the opportunity to come up with their own hierarchical system to help manage this process. | |||

This model is probably most closely related to the kind of social systems used in the communes in the 1970s. In attempting to create a "jeffersonian democracy", they used cybernetics and network theory to create non-hierarchical systems where any member of the group would have equal say in the workings of the commune. Feedback is most important in this scenario if the participants are to manage playing the game democratically. Alternatively, the group may decide to modify the network topology into a more hierarchical structure (either intentionally or by the natural development of a social order amongst the group) in order to better manage the system in Micropolis. | |||

===Section 2=== | ===Section 2=== | ||

Finally, I plan on opening up a discussion about what conclusions we can draw from the first two sections. I am curious to discover how the participants feel the game reflects and diverges from reality, and if the game can tell us anything about how cybernetics might be applied to the management of society ''IRL''. I am also interested in how their decisions were affected by the bias of the game's interface (for example, how it forces a grid-model or rewards a particular type of city), and also by the actions of the other participants - for example, how did the social systems created in the workshop affect the design of the cities? In particular, I am curious to hear how people feel the Cold War roots of this kind systems-oriented culture prejudice our daily lives today. I can deem the workshop a success if it triggers a lively discussion centered around this question. | |||

Latest revision as of 13:25, 3 October 2012

Previous Version

A previous version of this plan can be found here.

About

I am currently planning a workshop that deals with the "cybernetic view of society" - essentially the post-World War II tendency to view society as a cybernetic entity whose behaviour can be managed and predicted through the use of mathematical systems. In my research last year, I proposed that this "cybernetic view of society" was an ideology born out of the complexity of Cold War politics, an attempt to regain some sense of control over the myriad of possible events that could tip the world into nuclear war.

In Steve Rushton's lecture at the Masters of Reality launch, he spoke about how American was transitioning from a manufacturing-based economy to an information economy. With cybernetics provided the underlying logic to the management of this transition, cybernetics left the military domain and began to form an integral part of the workings of civil society itself. Cybernetic concepts were assimilated into management systems in corporations, municipal and governmental strategy, visual art/music/film/literature, environmental science, and the mass media's understanding of the world. The result was the formation of what Jack Burnham calls a "systems-oriented culture, where change emanates not from things, but from the way things are done." source

The game Micropolis (the open source version of Sim City) encapsulates these ideas in the form of an interactive game, in which the goal is to build a metropolitan utopia in an empty virtual landscape while trying to manage municipal finances, keep the population happy, and strike a balance between the division of labour in the city. The game presents the player with a simplified set of rules and some starting capital, and from then on he/she must decide how the city is to function without much further prompt from the game, other than basic feedback about crime rate or public opinion of tax rates, for example. The game presents the player with an exaggerated cybernetic view of society: the rules of the game are mutually dependent, affecting each other through feedback loops, recursion, and cellular automata-like systems. The result is an impression of a city inhabited by people (referred to as Sims) with jobs, homes, and opinions on how the city is being run.

Methodology

The workshop is presented as a social experiment, a study of how people organise themselves when making decisions as a group. They will be presented with the brief to build a city within the game Micropolis, but there are not enough computers for all people to play the game individually. From this point, the participants have to decide how to proceed.

Why Micropolis?

Micropolis provides a link between two eras of computer technology: the Cold War period of game theory, statistical models, and the desire to simulate and predict the actions of the masses; and the rise in popularity of of the "personal computer" in the 1980s. Micropolis softens the cybernetic ideology inherited from the Cold War period and presents it as a "game" - not in a Von Neumann sense, but in the as a source of entertainment. Despite this, there are a number of fictional or problematic truths hidden within the game's interface that communicates a form of politics: Nuclear power vs Coal; Crime vs class; the automatic provision of a welfare system; and the various inputs that affect the satisfaction rating of the population. Above all, the game requires the participant to view the simulated society as a systematic entity, which draws quite direct parallels to the era of Cold War computing and various projects funded by the US Military from the 1940s up to today. I feel that Micropolis presents a good interface to unpack these two strands as a group.

Another reason I chose Micropolis is because of its history - it was one of the first popular city-building simulation computer games (designed to be played for entertainment), and has been adopted into the One Laptop Per Child project. The OLPC project is in many ways a product of the main aims of the countercultural ideology: democratising access to computer technology, and using it as an open educational platform. By participating in OLPC project, Micropolis remains a component of the belief that computers can somehow deliver a utopian society.

Outcomes

My aim with this workshop is to open a debate with the participants about the cybernetic view of society and systems-oriented culture in general. I am curious to hear how people feel we have gained from this transition, and how we might be adversely affected. I see the workshops as serving two purposes: firstly, they are an end in themselves - they are designed to encourage the participants to draw new conclusions about the systems that mediate our society, to question the necessity, and if/how they contribute to a better way of life. Secondly, I hope that the workshops can function as "field-research", and that I can use some of the feedback I receive from these workshops to inform my practice. I see great value in avoiding an insular and individualistic approach to my research this year: the formation of micro-communities for the duration of the workshops are integral to a practical understanding of my research.

Workshop Structure

Overview

The workshop structure will operate best with 6-10 participants, and over the course of a 2-3 hour session split into 2 sections. The first section lasts approximately 1.5 hours, beginning with a brief introduction to the game Micropolis. The participants then play the game either as a committee or individually (to be decided), making decisions together and trying to build a utopian metropolis. The final section takes the form of an open discussion about the first two sections of the workshop. Specifically, how the participants feel the lecture and the game relate to each other, and how both relate to their own experiences of 21st century society.

The workshop would require the following facilities:

- Table space for 6-10 participants

- Internet connection (ethernet for 6-10 participants, or wireless internet)

- If available, some computers (preferably with linux-based OS) which I could pre-install Micropolis on to save time.

- Projector/wall space or panel.

Section 1

The second section of the game is centered around playing Micropolis. At this point, I'm unsure of how to organise the group. There are a number of scenarios I can work with:

Scenario 1

Allow the participants to play individually using their own computers. This approach focuses on them managing the internal system of Micropolis, making their own decisions to construct their own idea of a fully-functional city.

This approach follows a topology in which the nodes are independent of one another, and are not networked, as in the thumbnail image on the right. It is a non-social and autocratic model: each participant relies on their own skills to develop their city.

This system can become dynamic if multiple participants decide to give each other advice. In this situation, a fluid mesh network may develop, and the participants will no longer be "islands", but can cause a social effect that will influence how they manage their individual cities.

Scenario 2

Ask the participants to form committees of 2-3 people and start playing the game. In this instance, the participants have to manage two systems - the internal system of the game, and also the social system constructed around them. They have to make decisions about how the city should be built as a group, providing each other with feedback about how they feel they should progress in the game.

This topology takes the form of a group of mini-networks, within which the participants can make decisions and consult with other on how the game is to be played. There is no hierarchical bias built into the networks, but one may emerge through the course of playing the game. The participants can also decide how to delegate: they can assign particular tasks to each other, or propose a time-share system, etc.

Scenario 3

Play the game as one group, so that all decisions must be made by a large committee. This will increase the variety of the social system, and may cause the decision-making process to become increasingly complex. I would give the participants the opportunity to come up with their own hierarchical system to help manage this process.

This model is probably most closely related to the kind of social systems used in the communes in the 1970s. In attempting to create a "jeffersonian democracy", they used cybernetics and network theory to create non-hierarchical systems where any member of the group would have equal say in the workings of the commune. Feedback is most important in this scenario if the participants are to manage playing the game democratically. Alternatively, the group may decide to modify the network topology into a more hierarchical structure (either intentionally or by the natural development of a social order amongst the group) in order to better manage the system in Micropolis.

Section 2

Finally, I plan on opening up a discussion about what conclusions we can draw from the first two sections. I am curious to discover how the participants feel the game reflects and diverges from reality, and if the game can tell us anything about how cybernetics might be applied to the management of society IRL. I am also interested in how their decisions were affected by the bias of the game's interface (for example, how it forces a grid-model or rewards a particular type of city), and also by the actions of the other participants - for example, how did the social systems created in the workshop affect the design of the cities? In particular, I am curious to hear how people feel the Cold War roots of this kind systems-oriented culture prejudice our daily lives today. I can deem the workshop a success if it triggers a lively discussion centered around this question.