User:Amy Suo Wu/annotated bibliography: Difference between revisions

Amy Suo Wu (talk | contribs) |

Amy Suo Wu (talk | contribs) |

||

| (13 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 27: | Line 27: | ||

In this lecture, Cramer sketches the field of conspiracy theory and cultural theory; Political Theology, Semiotics, Paranoia, Sublime, Underground Politics, Postmodernism, Overground Politics, Network, Media. I found his talk on conspiracy theory analyzed through a broad cultural perspective very relevant and inspiring for understanding various interconnecting themes (sublime, conspiracy theory, epistemological critique, (alternative) representations of truth/reality) in my own research. | In this lecture, Cramer sketches the field of conspiracy theory and cultural theory; Political Theology, Semiotics, Paranoia, Sublime, Underground Politics, Postmodernism, Overground Politics, Network, Media. I found his talk on conspiracy theory analyzed through a broad cultural perspective very relevant and inspiring for understanding various interconnecting themes (sublime, conspiracy theory, epistemological critique, (alternative) representations of truth/reality) in my own research. | ||

He defines the nature of conspiracy theories as targeting the gray area between religion and politics. Defining terms like exoteric as being the visible and official and esoteric as being invisible and hidden, Cramer talks about conspiracy as an esoteric undercurrent, an underground counterculture which contradicts official history. | He defines the nature of conspiracy theories as targeting the gray area between religion and politics. Defining terms like exoteric as being the visible and official and esoteric as being invisible and hidden, Cramer talks about conspiracy as an esoteric undercurrent, an underground counterculture which contradicts official history. Furthermore how both exoteric and esoteric fluculate between religion and politics, (political theology). He talks about the potentiality of conspiracy theories as hacking our understanding of truth because they construct alternative realities and disrupt common sense truth. They "could be in the very best cases be practical and philosophical or epistemological critiques." However, once they become exoteric, that is overground, they have the danger of turning into official politics e.g. the protocols of the elders of zion being disseminated by the Third Reich of Germany. | ||

Seen through semiotics (the study of the interpretation of signs), conspiracy theories can be thought of as hyper-semiotics or paranoid semiotics as is tries to form a theory of coherence even from the most accidental details. Cramer goes on to explain paranoia as the only form of irrationality that is 'perfectly rational - if not overly rational', because since it cannot deal with irrationality, it tries to compensate by rationalizing that which it cannot. Fear, uncertainty and doubt, as components in paranoia describe the aesthetic (in ancient greek: perception, sentiment or subjective judgement) dimensions of conspiracy theories. Since the 18th century, fear, uncertainty and doubt as an aesthetic mode is described as the Sublime. The nature of the Sublime is an overwhelming natural force that threatens human being, however in the 19th century the sublime gets detached from nature. | Seen through semiotics (the study of the interpretation of signs), conspiracy theories can be thought of as hyper-semiotics or paranoid semiotics as is tries to form a theory of coherence even from the most accidental details. Cramer goes on to explain paranoia as the only form of irrationality that is 'perfectly rational - if not overly rational', because since it cannot deal with irrationality, it tries to compensate by rationalizing that which it cannot. Fear, uncertainty and doubt, as components in paranoia describe the aesthetic (in ancient greek: perception, sentiment or subjective judgement) dimensions of conspiracy theories. Since the 18th century, fear, uncertainty and doubt as an aesthetic mode is described as the Sublime. The nature of the Sublime is an overwhelming natural force that threatens human being, however in the 19th century the sublime gets detached from nature. | ||

*watch it [http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TjbI8AQi3uA here] | *watch it [http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TjbI8AQi3uA here] | ||

==<span style="font-size:14px;">'''Stories about the Future: From Patterns of Expectation to Pattern Recognition by Veronica Hollinger. Science Fiction Studies, Vol. 33, No. 3 (Nov., 2006), pp. 452-472)'''</span>== | ==<span style="font-size:14px;">'''Stories about the Future: From Patterns of Expectation to Pattern Recognition by Veronica Hollinger. Science Fiction Studies, Vol. 33, No. 3 (Nov., 2006), pp. 452-472)'''</span>== | ||

| Line 58: | Line 55: | ||

==<span style="font-size:14px;">'''The Reform of Time. Magic and Modernity, 2001, Maureen Perkins. Pluto Press, London.'''</span>== | ==<span style="font-size:14px;">'''The Reform of Time. Magic and Modernity, 2001, Maureen Perkins. Pluto Press, London.'''</span>== | ||

Maureen Perkins main thesis is that the 19th century marginalisation of ‘superstition’ was a part of a social history of time management. What is relevant for my research is her tracings of the changing definition of 'superstition' and through this Perkins reveals how definitions of knowledge changes according to hegemonic ideas in time. Her writing has provided me with grounded examples which is the foundation of my research question: how acceptable knowledge and its value is constructed. Her examples drawn mostly from 19th century Britain, show that epistemological undertakings were underpinned by social and economic endeavors lead by political agenda. What counted as 'knowledge', the value of information, was dictated by doctrines of progress, a project that had implications in the development of modern consumerism. It is also helpful that she references David Spadafora (The Idea of Progress in Eighteenth-Century Britain, 1990) as coining the distinction between ''idea'' of progress and various ''doctrines'' of progress in a social context, the former term conveying a belief in improvement or change in a desirable direction, while the latter signifies the expression given to that belief in a particular social group, such as writers on education. | |||

Her book explores how we conceptualize human agency, that of the interplay between free will vs determinism (individual struggle vs social structure) throughout different time frames in history. Starting from the 19th century, a strengthened belief in human agency due to reform movements which represented free will as the individual's potential for self-improvement to contribute to a wider social good, took place against the backdrop of the doctrine of progress. This is exemplified in the invention of blank calendars symbolizing a tabula rasa of opportunity on which members of society could write their future, increasing the emphasis on individual responsibility. The publication of the first Letts diary in 1812 originated ‘a new [future focused] concept of diary-keeping completely different from the traditional use as a personal historical record’. She continues to write that progress in its technological form is constantly held up to society as the justification for the advance of capitalism. | Her book explores how we conceptualize human agency, that of the interplay between free will vs determinism (individual struggle vs social structure) throughout different time frames in history. Starting from the 19th century, a strengthened belief in human agency due to reform movements which represented free will as the individual's potential for self-improvement to contribute to a wider social good, took place against the backdrop of the doctrine of progress. This is exemplified in the invention of blank calendars symbolizing a tabula rasa of opportunity on which members of society could write their future, increasing the emphasis on individual responsibility. The publication of the first Letts diary in 1812 originated ‘a new [future focused] concept of diary-keeping completely different from the traditional use as a personal historical record’. She continues to write that progress in its technological form is constantly held up to society as the justification for the advance of capitalism. | ||

| Line 77: | Line 74: | ||

Amid 19th century industrially booming England, time was associated more and more with industry, both concerning efficient functioning and personal diligence. Not only was wasting time sinful and careful stewardship of it a virtue, but time also became seen as 'man's only property'. Time obtained a new treatment of currency to be guarded and owned. With the conflation of time and labour and advances in technology, the measurement of time became increasingly important and precise – which would give rise to the the commodification of time. Also, history as a discipline started to rise and saw a need to measure present time more efficiently and aspired to categorise past time more scientifically. Quantifiable data and royal birthdays in almanacs replaced giants and mermaids. The British Almanac, launched in 1828 by none other than Charles Knight, is one of the first examples of this genre being taken up as a vehicle for reform. On what seemed to be a personal crusade, Knight was the first of several 19th century campaigner to make use of the almanac to advance particular social and political attitudes (p.52), one which attempted to transform social consciousness for the reception the doctrine of progress.(p.58) In his version of the almanac, the moon changes usually featured in all the almanacs of the time were literally marginalized. In its place, at the head of the calendar, was information that would make use of the mechanical clock easier and space left over were filled with titles like "Useful Remarks". This signaled a change in the way in which time was measured. Moreover, a promotion of statistics was a prominent feature: "29 pages devoted to the heights of mountains in Europe indicate the type of numerical data which were eventually to replace the company's works of astrology and entertainment." (p.55) | Amid 19th century industrially booming England, time was associated more and more with industry, both concerning efficient functioning and personal diligence. Not only was wasting time sinful and careful stewardship of it a virtue, but time also became seen as 'man's only property'. Time obtained a new treatment of currency to be guarded and owned. With the conflation of time and labour and advances in technology, the measurement of time became increasingly important and precise – which would give rise to the the commodification of time. Also, history as a discipline started to rise and saw a need to measure present time more efficiently and aspired to categorise past time more scientifically. Quantifiable data and royal birthdays in almanacs replaced giants and mermaids. The British Almanac, launched in 1828 by none other than Charles Knight, is one of the first examples of this genre being taken up as a vehicle for reform. On what seemed to be a personal crusade, Knight was the first of several 19th century campaigner to make use of the almanac to advance particular social and political attitudes (p.52), one which attempted to transform social consciousness for the reception the doctrine of progress.(p.58) In his version of the almanac, the moon changes usually featured in all the almanacs of the time were literally marginalized. In its place, at the head of the calendar, was information that would make use of the mechanical clock easier and space left over were filled with titles like "Useful Remarks". This signaled a change in the way in which time was measured. Moreover, a promotion of statistics was a prominent feature: "29 pages devoted to the heights of mountains in Europe indicate the type of numerical data which were eventually to replace the company's works of astrology and entertainment." (p.55) | ||

Perkins argues that the aim to tighten how prophecy was | Perkins argues that the aim to tighten how prophecy was instrumentalised was not only a story of elite domination and social control. The sheer popularity is one that reflects how this tradition has not survived, a term that carries connotations of a persistence of old forms, but rather continued, a term which denotes new meanings and new boundaries. For example, prophecy being replaced by political and economic forecasting and science fiction, and weather prediction metaphosed into weather forecasts issued by government meteorologist. (p.11) | ||

==<span style="font-size:14px;">'''Video annotation of "Way of the Dream", a documentary featuring Jungian psychologist, Marie Louise von Franz'''</span> == | ==<span style="font-size:14px;">'''Video annotation of "Way of the Dream", a documentary featuring Jungian psychologist, Marie Louise von Franz'''</span> == | ||

| Line 91: | Line 85: | ||

==<span style="font-size:14px;">'''On Divination and Synchronicity : The Psychology of Meaningful Chance Studies in Jungian Psychology by Marie-Luise von Franz, 1980. Inner City Books, Canada.'''</span>== | ==<span style="font-size:14px;">'''On Divination and Synchronicity : The Psychology of Meaningful Chance Studies in Jungian Psychology by Marie-Luise von Franz, 1980. Inner City Books, Canada.'''</span>== | ||

This publication is based on a transcription by Miss Una Thomas of the lecture series presented by Dr. von Franz at the C.G. Jung Institute, Zürich, in the fall of 1969. This book is organized into four lecture themes. Lecture two titled Divination is what I'll annotate in detail. | This publication is based on a transcription by Miss Una Thomas of the lecture series presented by Dr. von Franz at the C.G. Jung Institute, Zürich, in the fall of 1969. This book is organized into four lecture themes. Lecture two titled Divination is what I'll annotate in detail. | ||

As a psychologist, Marie-Luise von Franz is intrigued by the one-sided emotional conviction of statistical truth held by modern scientists. She wants to know why they are so emotionally tied to the idea that the calculus of probability or statistics is the truth. Thus by psychoanalytical means she investigates the depths of this thinking by going back and looking at the origin of this belief: the workings of an (number) archetype. | As a psychologist, Marie-Luise von Franz is intrigued by the one-sided emotional conviction of statistical truth held by modern scientists. She wants to know why they are so emotionally tied to the idea that the calculus of probability or statistics is the truth. Thus by psychoanalytical means she investigates the depths of this thinking by going back and looking at the origin of this belief: the workings of an (number) archetype. | ||

Dr. von Franz speculates that counting probably originated first with counting aids or reckoning aids (pebbles, stones, sticks..etc), which | Dr. von Franz speculates that counting probably originated first with counting aids or reckoning aids (pebbles, stones, sticks..etc), which were a way for human consciousness to get a hold of number. For primitive man, they owned as far as they could count and then the rest would be infinity - the godhead. For many tribes the concept of the group or 'many' covers the concept of the infinite. Nowadays, through mathematics and advance technology, we have more means to handle the many, the infinite. However, if man believes that he can handle an infinite series of natural numbers, that is an inflation, an identification with the archetype of the Self, or of the godhead. She compares this to making the same fatal mistake of thinking that a statistical truth ''is'' the truth, for we are really only handling an abstract concept and not reality itself, and into that thought then sneaks identification with the godhead in which one secretly believes that they can master nature and find the truth about everything. | ||

In writing about probability she talks the irrational nature of a single event (number) and how modern mathematicians thus needs to project them by a specific procedure onto the background of infinite possibilities to cope with them. The secret in probability is repetition: the more repeats, the more accurate the probability. They ignore the individual and simply deal with it as a ''class'', a group. She muses, "[m]athematicians are very honest people; they never deny that the single number has irrational, individual qualities, they are simply not interested". Or as the German mathematician and theoretical physicist, Hermann Weyl says, "ignore the single integer." Therefore the concept of average is an abstraction existing only in our minds: it doesn't actually exist, for the actual accumulation of people is an accumulation of unique cases. The calculus of probability is a mental artifact. | In writing about probability she talks about the irrational nature of a single event (number) and how modern mathematicians thus needs to project them by a specific procedure onto the background of infinite possibilities to cope with them. The secret in probability is repetition: the more repeats, the more accurate the probability. They ignore the individual and simply deal with it as a ''class'', a group. She muses, "[m]athematicians are very honest people; they never deny that the single number has irrational, individual qualities, they are simply not interested". Or as the German mathematician and theoretical physicist, Hermann Weyl says, "ignore the single integer." Therefore the concept of average is an abstraction existing only in our minds: it doesn't actually exist, for the actual accumulation of people is an accumulation of unique cases. The calculus of probability is a mental artifact. | ||

Similar to Barbara Tedlocks (below) text, she talks about how the personality of the medium acts as the filter of the information. She explains about how one can only have empathy into certain human states that the medium has experienced themselves. | Similar to Barbara Tedlocks (below) text, she talks about how the personality of the medium acts as the filter of the information. She explains about how one can only have empathy into certain human states that the medium has experienced for themselves. | ||

Non-number divinations techniques are based on some kind of chaotic pattern, which is exactly like the modern psychological Rorschach test. Dr. von Franz argues that the Rorschach test is a procedure that rediscovered the primitive divination technique of using chaotic patterns. Looking at chaotic patterns allows one to project what the unconscious is fantasying or dreaming about by means of confusing the conscious thoughts. She explains: "one cannot make head nor tail of a chaotic pattern; one is bewildered and that moment of bewilderment brings up the intuition from the unconscious [...] and through the absolute knowledge in the unconscious one gets information about one's inner and outer situation." That is the working principle of using arbitrary patterns. The real beginning of science was when chaotic patterns were put into some ordered way. The step of going from the random pattern, the Rorschach pattern, as a source of information, to the pattern which contains a geometrical or numerical order, is coincident with the possibility of forming a general theory. She criticizes modern science for pulling apart theory and experiment and how we have specifically developed mathematical ordering leaving the working principle of chaos and chance in its archaic form. | Non-number divinations techniques are based on some kind of chaotic pattern, which is exactly like the modern psychological Rorschach test. Dr. von Franz argues that the Rorschach test is a procedure that rediscovered the primitive divination technique of using chaotic patterns. Looking at chaotic patterns allows one to project what the unconscious is fantasying or dreaming about by means of confusing the conscious thoughts. She explains: "one cannot make head nor tail of a chaotic pattern; one is bewildered and that moment of bewilderment brings up the intuition from the unconscious [...] and through the absolute knowledge in the unconscious one gets information about one's inner and outer situation." That is the working principle of using arbitrary patterns. The real beginning of science was when chaotic patterns were put into some ordered way. The step of going from the random pattern, the Rorschach pattern, as a source of information, to the pattern which contains a geometrical or numerical order, is coincident with the possibility of forming a general theory. She criticizes modern science for pulling apart theory and experiment and how we have specifically developed mathematical ordering leaving the working principle of chaos and chance in its archaic form. | ||

| Line 105: | Line 99: | ||

The idea of chance or chance events in scientific experiments are seen as a nuisance to be eliminated by as much repetition as possible. Naturally chance is an objective factor and exists, but in science one speaks of a chance ''accident'', something to be regretted. She concludes by looking at the different methodologies between a modern, physical scientific experiment and a divination oracle. The experiments eliminate chance, the oracle makes chance the centre; the experiment is based on repetition, the oracle is based on the one unique act. The experiment is based on a probability calculus and the oracle uses the unique, individual number as a source of information. | The idea of chance or chance events in scientific experiments are seen as a nuisance to be eliminated by as much repetition as possible. Naturally chance is an objective factor and exists, but in science one speaks of a chance ''accident'', something to be regretted. She concludes by looking at the different methodologies between a modern, physical scientific experiment and a divination oracle. The experiments eliminate chance, the oracle makes chance the centre; the experiment is based on repetition, the oracle is based on the one unique act. The experiment is based on a probability calculus and the oracle uses the unique, individual number as a source of information. | ||

'''Lecture one: Coincidence in psychical research Psychological aspects. | |||

coming soon''' | |||

==<span style="font-size:14px;">'''Divination as a Way of Knowing: Embodiment, Visualisation, Narrative, and Interpretation. By Barbara Tedlock. Folklore, Vol. 112, No. 2 (Oct., 2001), pp. 189-197 published by Taylor and Francis, Ltd'''</span>== | ==<span style="font-size:14px;">'''Divination as a Way of Knowing: Embodiment, Visualisation, Narrative, and Interpretation. By Barbara Tedlock. Folklore, Vol. 112, No. 2 (Oct., 2001), pp. 189-197 published by Taylor and Francis, Ltd'''</span>== | ||

| Line 114: | Line 110: | ||

Similarly, in C. Nadia Seremetakis's text Divination, media, and the networked body of modernity, she quotes Comaroff and Comaroff; "[divinatory practices] register the impact of large-scale transformations on local worlds. Indeed, [their] very durability stems from a genius for making the language of intimate, interpersonal affect speak of more abstract social forces. . . . Because witches distill complex material and social processes into comprehensible human motives, then, they tend to figure in narratives that . . . map translocal scenes onto local landscapes, that translate translocal discourses into local vocabularies of cause and effect. [Comaroff and Comaroff 1999:285]" | Similarly, in C. Nadia Seremetakis's text Divination, media, and the networked body of modernity, she quotes Comaroff and Comaroff; "[divinatory practices] register the impact of large-scale transformations on local worlds. Indeed, [their] very durability stems from a genius for making the language of intimate, interpersonal affect speak of more abstract social forces. . . . Because witches distill complex material and social processes into comprehensible human motives, then, they tend to figure in narratives that . . . map translocal scenes onto local landscapes, that translate translocal discourses into local vocabularies of cause and effect. [Comaroff and Comaroff 1999:285]" | ||

What is interesting in this research article is that the writer introduces a brief history of the use of the terms "divination" and "mantic". She writes that the English word "divination" having its roots in Latin (divinus) meaning belonging or relating to a deity and divine, was actually an improvement on the original Greek word mantike. This word is derived from mania, which meant madness, raving, insanity, or inspiration. Plato describes another ancient Greek term oionistic, that referred to the inductive art of the uninspired and sane who inquire purely from human reasoning into the future by observing bird flights and other omens, concluding that "both in name and in fact, madness is nobler than sanity [for] the first proceeds from a god, the other from mere men" (Helmbold and Rabinowitz 1956, 245). This is interesting in relation to how Perkins (1996) describes the perceptions of the different kinds of astrology in the 19th century. What was once seen as dull and an uninspired way of inducing a conclusion came to be acceptable knowledge guided by reason, while intuitive forms became deemed as superstitious. This contrasts serves to highlights the how the ever-changing nature of knowledge and its following perception is valued and shaped by ideology. The term mantike originally referring only to prophecy consisting of a kind of mania, madness or ecstasy of divine possession later became extended to also mean oionistic – inductive, or artificial divination (technike) as well. | What is interesting in this research article is that the writer introduces a brief history of the use of the terms "divination" and "mantic". She writes that the English word "divination" having its roots in Latin (divinus) meaning belonging or relating to a deity and divine, was actually an improvement on the original Greek word ''mantike''. This word is derived from mania, which meant madness, raving, insanity, or inspiration. Plato describes another ancient Greek term ''oionistic'', that referred to the inductive art of the uninspired and sane who inquire purely from human reasoning into the future by observing bird flights and other omens, concluding that "both in name and in fact, madness is nobler than sanity [for] the first proceeds from a god, the other from mere men" (Helmbold and Rabinowitz 1956, 245). This is interesting in relation to how Perkins (1996) describes the perceptions of the different kinds of astrology in the 19th century. What was once seen as dull and an uninspired way of inducing a conclusion came to be acceptable knowledge guided by reason, while intuitive forms became deemed as superstitious. This contrasts serves to highlights the how the ever-changing nature of knowledge and its following perception is valued and shaped by discourse and ideology. The term mantike originally referring only to prophecy consisting of a kind of mania, madness or ecstasy of divine possession later became extended to also mean oionistic – inductive, or artificial divination (technike) as well. | ||

Tedlock writes that over the years, many so-called inductive or rational forms of divination have been compared with Western scientific techniques. Anthropologist Emile Durkheim and Marcel Mauss, argued that the science of divination was a system of classification. Marlene Dobkin labelled divination the non-Western equivalent of various psychological tests including TATs and Rorschachs (Dobkin 1969, 140; <span style="color:red;">von Franz</span>), while Alan Harwood called divination an aetiology or science of causes (Harwood 1970, 111). Divination has also been categorised as a diagnostic procedure (Ackerknect 1971, 168; Fabrega and Silver 1973, 38), and June Nash coined a new word for divination – sociopsy – which she argued was comparable to biopsy in Western medicine (Nash 1967, 133). As these analogies between divination and science indicate, the English term retains a strongly Roman rather than a Greek flavour. | |||

==<span style="font-size:14px;">'''Chapter One: "The work of representation” in Representation: cultural representations and signifying practices by Stuart Hall. 1997, London: Sage. '''</span>== | |||

1) The concept of 'discourse', from signs(relations of meanings) to culture(relations of power).<br> | |||

Foucault shifted and opened up the meaning of term 'discourse' from a linguistic concept (broad and inclusive idea of signs: visual images, sounds, facial expressions .etc ) to encapsulate a larger system of representation beyond signs. Like the semioticians, Foucault was a 'constructionist', however unlike a then, he was not concerned with meaning through language but how knowledge was produced through discourse. For Foucault 'discourse' is about what one says (language) as much as what one does (practice). More specifically, 'discourse' meant 'a group of statements which provide a language (terminology/jargon)for talking about – a way of representing the knowledge about – a particulate topic at a particular historical moment. Discourse is about the production of knowledge through language, but since all social practices entail meaning, and meanings shape and influence what we do – our conduct – all practices have a discursive aspect.' By defining and producing the objects of our knowledge, it regulates its meaning and influences how ideas are put into practice and used to regulate conduct of others. Just as it governs certain acceptable forms of truth, it also defines limitations and restricts the construction of knowledge itself – of how reality is perceived and produced. | |||

Foucault also historicized discourse. He maintained that discourse, representation, knowledge and truth are historically grounded; things meant something and were true, only within a specific historical context. e.g the idea of hysterical women only existed after the 19th century. | |||

Discourse (that which constructs the topic) --> Episteme (event/historical moment) --> Discursive formation (whenever these discursive events 'refer to the same object, share the same style and…support a strategy---a common institutional, administrative or political drift and pattern') | |||

2) power and knowledge; from discourse to power/knowledge <br> | |||

He focused on the relationship between knowledge and power, and how power operated within what he called an institutional apparatus and its technologies (techniques). Apparatus includes linguistic and non-linguistic elements – regulations, laws, morality, scientific statements etc….The apparatus is thus always inscribed in a play of power, but it is also always linked to certain co-ordinates of knowledge…. This is what the apparatus consists in: strategies of relations of forces supporting and supported by types of knowledge' | |||

The main difference between Foucault's understanding of 'discourse' and Marxist theories of 'ideology' was that | |||

he rejected the reductionism of all the relation between knowledge and power to a question of ''class'' power and ''class'' interests. | |||

Foucault argued that not only is knowledge always a form of power, but power is implicated in the questions of whether and in what circumstances knowledge is to be applied or not. This question of the application and effectiveness of power/knowledge was more important, he thought, than the question of its 'truth'. | |||

Knowledge linked to power, not only assumes the authority of 'the truth' but has the power to ''make itself true''. All knowledge, once applied in the real world, has real effects, and in that sense at least,' becomes true'. Knowledge, once used to regulate the conduct of others, entails constraint, regulation and the disciplining of practices. Thus, 'there is no power relation without the correlative constitution of a field of knowledge, nor any knowledge that does not presuppose and constitute at the same time, power relations'. | |||

Knowledge does not operate in a void: it has to work through certain technologies and strategies of application, in specific situations, historical contexts and institutional regimes. | |||

3) the question of the 'subject' <br> | |||

coming soon... | |||

==PI, movie by Darren Aronofsky. 1998== | |||

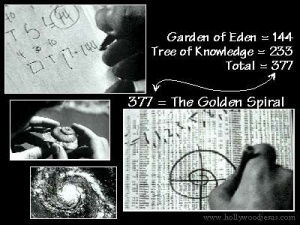

Aronofsky's movie is about the obsessive mind of the protagonists, Max Cohen. This movie is underlined by opposing views of the universe as an extremely complex and chaotic system verses an ordered universe enabling prediction. After attempts to predict the stock market, Max's computer crashes leaving a 216-digit number. This starts the spiral of the obsessive search for mathematical perfection (idealism) in the Torah and stock market. What this movie reveals is that in the pursuit of order - the universal laws of nature, the paranoiac behavior will try to find a way to connect everything including the irrational. Max, mentor, Sol saids to him: "when your mind comes obsessed with anything, you will filter anything else out and find the thing everywhere………as soon as you discard scientific rigor, your no longer a mathematician, your a numerologist." | |||

[[image:Pi03.jpg | 300px ]] [[image:Pi-0.jpg |368px]] | |||

[[image:Pi movie-vi.jpg | 500px]] | |||

Latest revision as of 00:33, 17 December 2012

Why Has Critique Run Out of Steam? From Matters of Fact to Matters of Concern, 2004, Bruno Latour. Article from Critical Inquiry, a journal of Art, Culture and Politics, Published by the University of Chicago.

Bruno Latours article questions the ethics of critical inquiry. Beginning with global warming as an example to demonstrate his concern about the misuse of social critique, Latour mourns over the fact that people are abusing the techniques he was pioneering to detect the real prejudices hidden behind the appearance of objective statements. "[T]here is now, an excess of distrust of good matter disguised as bad ideological bias." (p. 227) He spent many years undermining the certainty of scientific matters of fact, however these strategies he helped to created are now used to attack the 'good' facts scientists rightfully fought. He feels the weapons of social critique have now mutated and have been mutinously deployed to attack what it used to defend. Conspiracy theories for Latour are an absurd deformation of scientific argument. With regret, the global warming theory is something that is being questioned by naive believers for its foundation of reality based on a lack of certainty. He feels complicit in being a 'mad scientist' for letting this virus of critical inquiry unleash without control.

Latour relates the difference between what he calls matters of fact and matters of concern to Heideggar's mediation on the word 'thing' as having strong connection to a quasi-judiciary assembly. This ancient word 'thing', once designated a site in which people did their dealing and disputes, has become in modern usage, a word which designates what is out there, what lies out of any dispute, out of language. Thus matters of fact can be seen as an object, out there, and matters of concern can be understood as issues in there - a gathering. In the case of global warming, he feels like it was an object (fact) that has been degraded into a thing (discussion).

He poses two approaches are that used by the contemporary critical scene: the fairy (anti-fetish) and fact position. Both these positions are based on the premise of debunking one another. The anti-fetish position reveals the power of free will as own power that is projected such as culture and art, and the fact position reveals powerful causalities of external forces such as economics, genetics. etc. His critique is that social critique can choose either one to argue for what you don't believe (anti-fetish position) and use another for what you do believe in (fact position), without any consistency. Latour stands for a critic who doesn't debunk but assembles, one who offers the participants arenas in which to gather.

On the one hand, I can understand that Latour is trying to defend urgent issues like global warming as something that should not be primarily regarded as a lack of scientific certainty, but should rather be regarded as a matter of fact. On the other hand, however, I find it a little hypocritical that while he stands to offer participants spaces in which to gather as a practice of matters of concern, the global warming matter of fact should be left alone and not be turned into a discussion. Though I find it helpful to use his distinctions and definitions of fact and gathering, I would like to re-visit the global warming case (perhaps against his wishes) as a matter of concern.

The Weather Imagination, 2005, Luian Boia. Reaktion books, London.

Boia traces human's relationship and imagination of the weather and sets the field to discuss how discourses like ideology and politics have mediated questions of climate change causality as either a god/nature inflicted phenomenon or a human caused phenomenon. As a historian, he traces texts ranging from scholarly manuscripts of medieval Europe to scientific literature to modern sci-fi writings to reveal an ever-constant malaise of crisis expressed through an imagined catastrophe. His position in the global warming debate is neither a believer or non-believer, rather he calls into question, both the certainty of scientific (statistical) models and the human propensity for catastrophism. "Our search for explanation must go beyond the factual basis of the (global warming) theory and focus on the reasons for its dominance." In a sense his position is quite similar to Bruno Latours 2004 article, in that they both recognize that the issue is not the factual foundation but rather the issues that govern its outcomes. That said, I feel like Boia is more skeptical of the prestige that scientific models holds, a position that is more closely related to the Latours' constructivist position held in his eariler works (Science in Action, Labortory life).

This book is organized into three sections, however the third section is most relevant for my research. (The first is the anthropological and psychological analysis of our relation to climate as a means to explaining human diversity. i.e. Human beings are different because they live under different skies. The second is historical; climate as a way of illuminating the progress of history. Since the 19th century, the climate was regarded as one of the casual factors in the historical development and the radically different destinies of civilizations. ) The third is climate and catastrophe. The prototype of this kind of over-dramatization is the Biblical Flood, evoking an overwhelming natural force threatening humanity. The nature of catastrophe is the nature of what Florian in Tangent Conspiracies (annotation below) describes as the Sublime. In this section, he traces the religious historical interpretation of catastrophes as apocalyptic notions of the universal Flood which served to be a moralistic concept of human destiny. He highlights historical relationships to climate as once being the arsenal of the forces of divine justice and how it became demoted, due to The Enlightenment, to 'natural phenomena'. He continues, however, that the anxiety felt about the sins of men against God has been maintained today in the "form of a preoccupation with the 'end of civilization'". Throughout the ages, natural phenomena is integrated into interpretative systems which the interpretations are the manifestations of the socio-ideological tensions of the time; mostly likely to result in war and revolution, rather than end of the world.

In the concatenation of disasters beginning from the 1900's, the Flood acquired a new equally frightening variant in the form of a 'human tide'. He explains that this was brought on by the interchangeability of anxiety toward nature and people, the world wars and the increasingly sense of the 'other'. The fear of 'technological flood' is what Boia describes as a catastrophe based on humanities ability to destroy itself. There are however, a plethora of evidence to prove and disprove global warming theories based on different ideological grounds. He also tries to emphasize that we are tempted to confuse 'existing reality' with the 'virtual reality' of (scientific) models, as they are "…simplified, coherent and synthetic versions of a certain dimension of reality or determined process. They are extremely useful as long as we remember that they are not the real thing: they are methodological fictions" (p.177). It is also interesting to note that the early meteorological recording of medieval europe focused on the usual, the excesses, the dramatic - an attitude that still prevails today exemplified by the operations of media. Harmless consequences are of no interest to the media, as it is the most dramatic versions that will receive the most publicity. This of course fuels our imagination for catastrophes.

Tangent Conspiracies, 2006, Florian Cramer. A lecture given at a V2 event (Rotterdam) by the same name.

In this lecture, Cramer sketches the field of conspiracy theory and cultural theory; Political Theology, Semiotics, Paranoia, Sublime, Underground Politics, Postmodernism, Overground Politics, Network, Media. I found his talk on conspiracy theory analyzed through a broad cultural perspective very relevant and inspiring for understanding various interconnecting themes (sublime, conspiracy theory, epistemological critique, (alternative) representations of truth/reality) in my own research.

He defines the nature of conspiracy theories as targeting the gray area between religion and politics. Defining terms like exoteric as being the visible and official and esoteric as being invisible and hidden, Cramer talks about conspiracy as an esoteric undercurrent, an underground counterculture which contradicts official history. Furthermore how both exoteric and esoteric fluculate between religion and politics, (political theology). He talks about the potentiality of conspiracy theories as hacking our understanding of truth because they construct alternative realities and disrupt common sense truth. They "could be in the very best cases be practical and philosophical or epistemological critiques." However, once they become exoteric, that is overground, they have the danger of turning into official politics e.g. the protocols of the elders of zion being disseminated by the Third Reich of Germany.

Seen through semiotics (the study of the interpretation of signs), conspiracy theories can be thought of as hyper-semiotics or paranoid semiotics as is tries to form a theory of coherence even from the most accidental details. Cramer goes on to explain paranoia as the only form of irrationality that is 'perfectly rational - if not overly rational', because since it cannot deal with irrationality, it tries to compensate by rationalizing that which it cannot. Fear, uncertainty and doubt, as components in paranoia describe the aesthetic (in ancient greek: perception, sentiment or subjective judgement) dimensions of conspiracy theories. Since the 18th century, fear, uncertainty and doubt as an aesthetic mode is described as the Sublime. The nature of the Sublime is an overwhelming natural force that threatens human being, however in the 19th century the sublime gets detached from nature.

- watch it here

Stories about the Future: From Patterns of Expectation to Pattern Recognition by Veronica Hollinger. Science Fiction Studies, Vol. 33, No. 3 (Nov., 2006), pp. 452-472)

In this article, Hollinger reads three science-fiction novels (William Gibson's Pattern Recognition, 2003; Margaret Atwood's Oryx and Crake, 2003; and Greg Egan Schild's Ladder, 2001) as a series of significantly interrelated responses to the increasingly complex nature of the future in technoculture. Moreover, through studying the sf genre, she explores the problematic impact of the future – the future in/as technoculture – on the present.

The idea of the future-present describes "the phenomenology of a present infused with futurity, no longer like itself, no longer like the present." In our increasingly fast paced technoculture, perpetual change estranges us from "the past." Quoting Jonathan Benison, Hollinger writes "…our present in effect has started to make sense less as a continuation of the past than as an anticipation of the future, which it pre-empts or incorporates before it can ever arrive." This rupture with our past or the disappearance of a sense of history (one in which earlier social formations have attempted to preserve traditions) has lead inevitably to a loss of the "future", at least one that is open-ended fostering a sense of (utopian) possibility. The way in which we perceive the timespan of "now" is subject to incessant change, we live in a perpetual present that weakens the possibility to envision a meaningful transformation. As the duration of "now" has shortened, the future is also closer smothering futuristic imagination because change happens so abruptly, so violently, so profoundly. In Gibson's Pattern Recognition, Hubertus Bigend, the sinister businessman who represents the new world order of global corporate culture concludes that "We have no future because our present is too volatile.... We have only risk management. The spinning of a given moment's scenarios. Pattern recognition." Hollinger suggests that "the 'vocation' of science fiction has become "to dramatize our incapacity to imagine the future" -that is, to illustrate with the stories the inability to imagine something qualitatively different.

What is interesting is the notion of the "futuristic flu", a satirical diagnosis by Professor Istvan Csicsery-Ronay, Jr. on the sense of intrusion of technoscientific futurity. This condition which happens in a "time further in the future than the one in which we exist and choose infects the host present, reproducing itself in simulacra, until it destroys all the original chronocytes of the host imagination. The result is an increasingly acute sense that the shape of things to come has already been determined, undermining in the process the "morale and freedom necessary to create an open, 'conditional future'". Through studying these books from a genre that reflects a way of thinking about a sociopolitical present defined by radical and incessant technological transformation, Hollinger portrays the discourse of technoscience and it's preoccupation with futurity not so much as reducing alternative futures by materializing what it preempts immediately – thereby perpetuating 'now', but rather the inability to even fathom a distant future, one that is so inaccessible and opaque because the future-present is constant and blindingly close. Technological acceleration has inadvertently compressed time whereby we live in a kind of science-fictionalised present.

The Formula, What if you built a machine to predict the hit movies? By Malcolm Gladwell. New Yorker, Annals of Entertainment, October 16, 2006.

Malcolm Gladwell's article is about Epagogix, a prediction company based on the neural network system to estimate a screenplay's box-office performance before it gets made. However, underlying this report about prediction companies Gladwell is actually probing the problems of subjective and objective knowledge making even in today's technologically advanced environment. The article is deliberately centered around the people behind this business – Dick Copaken the lawyer, and his eclectic team consisting of people with a background in risk management and biochemistry. He begins by anchoring this thesis in a historical context by contrasting two opposing 'mindstates' propounded by David Hume(1711-1776) and Lord Kames (Henry Home 1896-1782) regarding the old philosophical debate of subjectivity and objectivity (idealism and materialism). Platinum Blue, a tech startup that does much the same using computer software in the music industry as Epagogix in the movie industry, is headed by Mike McCready who Gladwell labels under the Kames camp. Unlike 'Humeian' thought which is predicated on notion that there is no way to arrive at an objective truth exemplified in the expression, 'beauty lies in the eye of the beholder', Kamesian thought is predicated on the conviction that a rational system of rules exists external to our minds. It is not surprising then that Hume once referred Kames as "the most arrogant man in the world". In trying to strictly measure mathematical relationships among all of a songs structural components, Platinum Blue's software doesn't care about things such as the cleverness of lyrics, it only tries to measure and reduce subjective traits like beauty in an objective way. Gladwell provides a little background to Kames personal history as a 'brilliant lawyer' – and to be a good lawyer he writes, is to be invested with a reverence for rules believing in the power of broad patterns and rules rather than the authority of individuals or institutions.

Similar to Kames, Copaken is also a lawyer and possesses the same conviction that there is always a underlying pattern or system of rules to everything. In developing his own system for evaluating the commercial potential of stories, Copaken introduced a powerful kind of computerized learning system called an artificial neural network to Hollywood. Neural networks among other things are used for data mining – to look for patterns in very large amounts of data. This meant that screenplays were being treated as mathematical propositions using categories and scores to convert them into measurable data. Gladwell concludes that although it is easier to detect patterns using advanced tools to evaluate structural variables, it actually makes the task of filmmaking harder precisely because we cannot escape personal opinion. To know the rules in art doesn't necessary make you an artists.

The Reform of Time. Magic and Modernity, 2001, Maureen Perkins. Pluto Press, London.

Maureen Perkins main thesis is that the 19th century marginalisation of ‘superstition’ was a part of a social history of time management. What is relevant for my research is her tracings of the changing definition of 'superstition' and through this Perkins reveals how definitions of knowledge changes according to hegemonic ideas in time. Her writing has provided me with grounded examples which is the foundation of my research question: how acceptable knowledge and its value is constructed. Her examples drawn mostly from 19th century Britain, show that epistemological undertakings were underpinned by social and economic endeavors lead by political agenda. What counted as 'knowledge', the value of information, was dictated by doctrines of progress, a project that had implications in the development of modern consumerism. It is also helpful that she references David Spadafora (The Idea of Progress in Eighteenth-Century Britain, 1990) as coining the distinction between idea of progress and various doctrines of progress in a social context, the former term conveying a belief in improvement or change in a desirable direction, while the latter signifies the expression given to that belief in a particular social group, such as writers on education.

Her book explores how we conceptualize human agency, that of the interplay between free will vs determinism (individual struggle vs social structure) throughout different time frames in history. Starting from the 19th century, a strengthened belief in human agency due to reform movements which represented free will as the individual's potential for self-improvement to contribute to a wider social good, took place against the backdrop of the doctrine of progress. This is exemplified in the invention of blank calendars symbolizing a tabula rasa of opportunity on which members of society could write their future, increasing the emphasis on individual responsibility. The publication of the first Letts diary in 1812 originated ‘a new [future focused] concept of diary-keeping completely different from the traditional use as a personal historical record’. She continues to write that progress in its technological form is constantly held up to society as the justification for the advance of capitalism.

According to Max Webber, accurate prediction lay in the heart of rationalism. The principle of development inherent in the process of 'civilization' was driven by the use of calculation as a strategy of social action. As such, rationalism, another credo of the 19th century reform movements, set the chasm between what was considered a rational way to 'calculate' and the superstitious way (faulty understanding of nature, a definition in the late 18th century ) to predict. Statistical calculations superseded and marginalized older superstitious forecasts about the future. 'The rise of a culture of planning, is, in fact, a form of secular prediction'. Example starts with the suicide of Robert Fitzroy, the first head of the new governmental department of meteorology in England, because his weather forecasts in the newspapers proved to be disastrously wrong. As a result, the sensitivity towards such terms as prognostications, prophecy, or forecasts were tainted due to the association of practicing 'superstition'.

The phenomenon of prediction, once belonging in the realm of magic and prophecy, still has crucial importance to modern secular society. Perkins argues that modern forecasting, however has become a powerful means of excluding alternative interpretations of the future. "The so-called decline of magic, in the West at least, has allowed a linear, exclusive teleology of progress to dominate." Referencing Ziauddin Sardar, (Rescuing all our Futures: the Future of Futures Studies (Westport, Conn.: Praeger, 1999)), who suggested that the modern secular prediction helps to create community by excluding the possibility of difference: '[T]he act of prediction exhibits a way of thinking that is limited to a certain cultural understanding. Moreover, the act of prediction is part of a cultural worldview that constricts the future to being only one future, by assuming that it is already ‘out there’ in some sense, waiting to be discovered'.

Visions of the Future. Almanacs, Time and Cultural Change 1775-1870. 1996, Maureen Perkins. Clarendon Press, Oxford

Published five years earlier, 'Visions of the Future' was the foundation in which 'The Reform of Time' was built. In this book, Maureen Perkins finely combs through the history of almanacs as a genre from 1775-1870 in England. She illustrates through this history, a battleground that reflects the way in which social reformers helped to construct a discourse of acceptable knowledge in the formation of cultural capital by banishing the prolific popular culture of prediction, prophesy and astrology into the lowest ranks of literature. She gives very detailed and historical accounts of various almanacs, each with their own commercial, social or political agenda's. For my research, I am interested how the traditional form of almanacs were hijacked to became a place to educate, distribute, reinforce and criticize values that were at odds with their own. In 1827, as a part of the campaign to enlighten a rising literate class by replacing their existing faulty knowledge which reformers labelled as ignorant or 'superstitious', the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge (SDUK) chose to target the widespread of almanacs. Headed by Charles Knight, who sought to produce a respectable replacement to the potential 'divisiveness' of popular 'trash' reading for popular audiences, the SDUK aimed to marginalize superstition by establishing authority on scientific rational knowledge. Furthermore he also contributed to the triumph of the mass discourse of an idealized 'society of the text', a readership whose utilitarian values would acknowledge the grand narrative of useful knowledge. (p.45) A different understanding of time which was increasingly getting transformed by the rise of statistical measurement, rendered the the claims to predict the future as jumping across the flow of time (Newtonian Laws) out of the question.

Perkins continues to explores the two main forms of astrology which were initially utilized by social reformers to at the same time denounce one mode of thinking while promoting the other. The major difference between 'superstitious' judicial and 'factual' natural astrology was the fundamental role in the former by the usage of a diagram charting the heavens in which could be drawn up, consulted and interpreted by an astrologer. In contrast the latter applied information about planetary movement and lunar phase to physical phenomena such as growth of crops or administration of medicine, all of which were guided by reason. A part of this justified logic lie in the fact that natural astrology sometimes called 'moonlore', was employed by the Christian church in coordinating its moveable feats such as Easter on the phases of the moon, therefore Godly and approvable. While judicial astrology, a 'heathenish' divination not based on Christian principles, was popularly used to predict and prophecies weather and government remained suspect to civil authorities. As the closing of the 18th century and the early years of the 19th century was a time of political turmoil, it saw an upsurge of interest in ancient prophecies. Circulated by the printed word, the almanac would play a large role as a suitable means of popularizing the message of dissent and disaffection with inherited wealth and corruption. Politically subversive, radical almanacs promoted the importance and popularity of prophecy, while often at the same time mocking and denigrating the clergy. Prophecy was closely linked to Millenarianism, and authorities were fearful of the widespread expectation of an end to earthy government. (p.96-100) In 1824, the Vagrancy Act was implemented which provided for the prosecution of 'every person pretending or profession to tell Fortunes, or using any subtle Craft, Means or Device, by Palmistry or otherwise to deceive and impose on any of his Majesty's Subjects'. By the 1830's predicting the future using statistics had acquired the 'dignity of science'. (p.89-92)

Amid 19th century industrially booming England, time was associated more and more with industry, both concerning efficient functioning and personal diligence. Not only was wasting time sinful and careful stewardship of it a virtue, but time also became seen as 'man's only property'. Time obtained a new treatment of currency to be guarded and owned. With the conflation of time and labour and advances in technology, the measurement of time became increasingly important and precise – which would give rise to the the commodification of time. Also, history as a discipline started to rise and saw a need to measure present time more efficiently and aspired to categorise past time more scientifically. Quantifiable data and royal birthdays in almanacs replaced giants and mermaids. The British Almanac, launched in 1828 by none other than Charles Knight, is one of the first examples of this genre being taken up as a vehicle for reform. On what seemed to be a personal crusade, Knight was the first of several 19th century campaigner to make use of the almanac to advance particular social and political attitudes (p.52), one which attempted to transform social consciousness for the reception the doctrine of progress.(p.58) In his version of the almanac, the moon changes usually featured in all the almanacs of the time were literally marginalized. In its place, at the head of the calendar, was information that would make use of the mechanical clock easier and space left over were filled with titles like "Useful Remarks". This signaled a change in the way in which time was measured. Moreover, a promotion of statistics was a prominent feature: "29 pages devoted to the heights of mountains in Europe indicate the type of numerical data which were eventually to replace the company's works of astrology and entertainment." (p.55)

Perkins argues that the aim to tighten how prophecy was instrumentalised was not only a story of elite domination and social control. The sheer popularity is one that reflects how this tradition has not survived, a term that carries connotations of a persistence of old forms, but rather continued, a term which denotes new meanings and new boundaries. For example, prophecy being replaced by political and economic forecasting and science fiction, and weather prediction metaphosed into weather forecasts issued by government meteorologist. (p.11)

Video annotation of "Way of the Dream", a documentary featuring Jungian psychologist, Marie Louise von Franz

http://pzwart3.wdka.hro.nl/aa/resources/204/

On Divination and Synchronicity : The Psychology of Meaningful Chance Studies in Jungian Psychology by Marie-Luise von Franz, 1980. Inner City Books, Canada.

This publication is based on a transcription by Miss Una Thomas of the lecture series presented by Dr. von Franz at the C.G. Jung Institute, Zürich, in the fall of 1969. This book is organized into four lecture themes. Lecture two titled Divination is what I'll annotate in detail.

As a psychologist, Marie-Luise von Franz is intrigued by the one-sided emotional conviction of statistical truth held by modern scientists. She wants to know why they are so emotionally tied to the idea that the calculus of probability or statistics is the truth. Thus by psychoanalytical means she investigates the depths of this thinking by going back and looking at the origin of this belief: the workings of an (number) archetype.

Dr. von Franz speculates that counting probably originated first with counting aids or reckoning aids (pebbles, stones, sticks..etc), which were a way for human consciousness to get a hold of number. For primitive man, they owned as far as they could count and then the rest would be infinity - the godhead. For many tribes the concept of the group or 'many' covers the concept of the infinite. Nowadays, through mathematics and advance technology, we have more means to handle the many, the infinite. However, if man believes that he can handle an infinite series of natural numbers, that is an inflation, an identification with the archetype of the Self, or of the godhead. She compares this to making the same fatal mistake of thinking that a statistical truth is the truth, for we are really only handling an abstract concept and not reality itself, and into that thought then sneaks identification with the godhead in which one secretly believes that they can master nature and find the truth about everything.

In writing about probability she talks about the irrational nature of a single event (number) and how modern mathematicians thus needs to project them by a specific procedure onto the background of infinite possibilities to cope with them. The secret in probability is repetition: the more repeats, the more accurate the probability. They ignore the individual and simply deal with it as a class, a group. She muses, "[m]athematicians are very honest people; they never deny that the single number has irrational, individual qualities, they are simply not interested". Or as the German mathematician and theoretical physicist, Hermann Weyl says, "ignore the single integer." Therefore the concept of average is an abstraction existing only in our minds: it doesn't actually exist, for the actual accumulation of people is an accumulation of unique cases. The calculus of probability is a mental artifact.

Similar to Barbara Tedlocks (below) text, she talks about how the personality of the medium acts as the filter of the information. She explains about how one can only have empathy into certain human states that the medium has experienced for themselves.

Non-number divinations techniques are based on some kind of chaotic pattern, which is exactly like the modern psychological Rorschach test. Dr. von Franz argues that the Rorschach test is a procedure that rediscovered the primitive divination technique of using chaotic patterns. Looking at chaotic patterns allows one to project what the unconscious is fantasying or dreaming about by means of confusing the conscious thoughts. She explains: "one cannot make head nor tail of a chaotic pattern; one is bewildered and that moment of bewilderment brings up the intuition from the unconscious [...] and through the absolute knowledge in the unconscious one gets information about one's inner and outer situation." That is the working principle of using arbitrary patterns. The real beginning of science was when chaotic patterns were put into some ordered way. The step of going from the random pattern, the Rorschach pattern, as a source of information, to the pattern which contains a geometrical or numerical order, is coincident with the possibility of forming a general theory. She criticizes modern science for pulling apart theory and experiment and how we have specifically developed mathematical ordering leaving the working principle of chaos and chance in its archaic form.

The idea of chance or chance events in scientific experiments are seen as a nuisance to be eliminated by as much repetition as possible. Naturally chance is an objective factor and exists, but in science one speaks of a chance accident, something to be regretted. She concludes by looking at the different methodologies between a modern, physical scientific experiment and a divination oracle. The experiments eliminate chance, the oracle makes chance the centre; the experiment is based on repetition, the oracle is based on the one unique act. The experiment is based on a probability calculus and the oracle uses the unique, individual number as a source of information.

Lecture one: Coincidence in psychical research Psychological aspects. coming soon

Divination as a Way of Knowing: Embodiment, Visualisation, Narrative, and Interpretation. By Barbara Tedlock. Folklore, Vol. 112, No. 2 (Oct., 2001), pp. 189-197 published by Taylor and Francis, Ltd

Barbara Tedlock addresses the practice of divination as active process of knowledge making by exploring the unknown in order to elicit answers to questions beyond the range of ordinary human understanding. This involves complementary modes of cognition associated with primary process(presentational) and secondary process of thinking (representational). During a divination, diviners construct usable knowledge from oracular messages by linking diverse domains of representational information and symbolism with emotional or presentational experience. She writes about how inductive (rational), intuitive (non-rational) and interpretative narrative techniques as ways of knowing are simultaneously recognized and employed by diviners in their native language when elicited to form a theory of divination.

Tedlock also writes about the role of the diviner as "specialists who use the idea of moving from a boundless to a bounded realm of existence in their practice. Compared with their peers, diviners excel in insight, imagination, fluency in language, and knowledge of cultural traditions."

Similarly, in C. Nadia Seremetakis's text Divination, media, and the networked body of modernity, she quotes Comaroff and Comaroff; "[divinatory practices] register the impact of large-scale transformations on local worlds. Indeed, [their] very durability stems from a genius for making the language of intimate, interpersonal affect speak of more abstract social forces. . . . Because witches distill complex material and social processes into comprehensible human motives, then, they tend to figure in narratives that . . . map translocal scenes onto local landscapes, that translate translocal discourses into local vocabularies of cause and effect. [Comaroff and Comaroff 1999:285]"

What is interesting in this research article is that the writer introduces a brief history of the use of the terms "divination" and "mantic". She writes that the English word "divination" having its roots in Latin (divinus) meaning belonging or relating to a deity and divine, was actually an improvement on the original Greek word mantike. This word is derived from mania, which meant madness, raving, insanity, or inspiration. Plato describes another ancient Greek term oionistic, that referred to the inductive art of the uninspired and sane who inquire purely from human reasoning into the future by observing bird flights and other omens, concluding that "both in name and in fact, madness is nobler than sanity [for] the first proceeds from a god, the other from mere men" (Helmbold and Rabinowitz 1956, 245). This is interesting in relation to how Perkins (1996) describes the perceptions of the different kinds of astrology in the 19th century. What was once seen as dull and an uninspired way of inducing a conclusion came to be acceptable knowledge guided by reason, while intuitive forms became deemed as superstitious. This contrasts serves to highlights the how the ever-changing nature of knowledge and its following perception is valued and shaped by discourse and ideology. The term mantike originally referring only to prophecy consisting of a kind of mania, madness or ecstasy of divine possession later became extended to also mean oionistic – inductive, or artificial divination (technike) as well.

Tedlock writes that over the years, many so-called inductive or rational forms of divination have been compared with Western scientific techniques. Anthropologist Emile Durkheim and Marcel Mauss, argued that the science of divination was a system of classification. Marlene Dobkin labelled divination the non-Western equivalent of various psychological tests including TATs and Rorschachs (Dobkin 1969, 140; von Franz), while Alan Harwood called divination an aetiology or science of causes (Harwood 1970, 111). Divination has also been categorised as a diagnostic procedure (Ackerknect 1971, 168; Fabrega and Silver 1973, 38), and June Nash coined a new word for divination – sociopsy – which she argued was comparable to biopsy in Western medicine (Nash 1967, 133). As these analogies between divination and science indicate, the English term retains a strongly Roman rather than a Greek flavour.

Chapter One: "The work of representation” in Representation: cultural representations and signifying practices by Stuart Hall. 1997, London: Sage.

1) The concept of 'discourse', from signs(relations of meanings) to culture(relations of power).

Foucault shifted and opened up the meaning of term 'discourse' from a linguistic concept (broad and inclusive idea of signs: visual images, sounds, facial expressions .etc ) to encapsulate a larger system of representation beyond signs. Like the semioticians, Foucault was a 'constructionist', however unlike a then, he was not concerned with meaning through language but how knowledge was produced through discourse. For Foucault 'discourse' is about what one says (language) as much as what one does (practice). More specifically, 'discourse' meant 'a group of statements which provide a language (terminology/jargon)for talking about – a way of representing the knowledge about – a particulate topic at a particular historical moment. Discourse is about the production of knowledge through language, but since all social practices entail meaning, and meanings shape and influence what we do – our conduct – all practices have a discursive aspect.' By defining and producing the objects of our knowledge, it regulates its meaning and influences how ideas are put into practice and used to regulate conduct of others. Just as it governs certain acceptable forms of truth, it also defines limitations and restricts the construction of knowledge itself – of how reality is perceived and produced.

Foucault also historicized discourse. He maintained that discourse, representation, knowledge and truth are historically grounded; things meant something and were true, only within a specific historical context. e.g the idea of hysterical women only existed after the 19th century.

Discourse (that which constructs the topic) --> Episteme (event/historical moment) --> Discursive formation (whenever these discursive events 'refer to the same object, share the same style and…support a strategy---a common institutional, administrative or political drift and pattern')

2) power and knowledge; from discourse to power/knowledge

He focused on the relationship between knowledge and power, and how power operated within what he called an institutional apparatus and its technologies (techniques). Apparatus includes linguistic and non-linguistic elements – regulations, laws, morality, scientific statements etc….The apparatus is thus always inscribed in a play of power, but it is also always linked to certain co-ordinates of knowledge…. This is what the apparatus consists in: strategies of relations of forces supporting and supported by types of knowledge'

The main difference between Foucault's understanding of 'discourse' and Marxist theories of 'ideology' was that he rejected the reductionism of all the relation between knowledge and power to a question of class power and class interests.

Foucault argued that not only is knowledge always a form of power, but power is implicated in the questions of whether and in what circumstances knowledge is to be applied or not. This question of the application and effectiveness of power/knowledge was more important, he thought, than the question of its 'truth'.

Knowledge linked to power, not only assumes the authority of 'the truth' but has the power to make itself true. All knowledge, once applied in the real world, has real effects, and in that sense at least,' becomes true'. Knowledge, once used to regulate the conduct of others, entails constraint, regulation and the disciplining of practices. Thus, 'there is no power relation without the correlative constitution of a field of knowledge, nor any knowledge that does not presuppose and constitute at the same time, power relations'.

Knowledge does not operate in a void: it has to work through certain technologies and strategies of application, in specific situations, historical contexts and institutional regimes.

3) the question of the 'subject'

coming soon...

PI, movie by Darren Aronofsky. 1998

Aronofsky's movie is about the obsessive mind of the protagonists, Max Cohen. This movie is underlined by opposing views of the universe as an extremely complex and chaotic system verses an ordered universe enabling prediction. After attempts to predict the stock market, Max's computer crashes leaving a 216-digit number. This starts the spiral of the obsessive search for mathematical perfection (idealism) in the Torah and stock market. What this movie reveals is that in the pursuit of order - the universal laws of nature, the paranoiac behavior will try to find a way to connect everything including the irrational. Max, mentor, Sol saids to him: "when your mind comes obsessed with anything, you will filter anything else out and find the thing everywhere………as soon as you discard scientific rigor, your no longer a mathematician, your a numerologist."