User:Ssstephen/Reading/A Narrative Theory of Games: Difference between revisions

(Created page with "[https://www.researchgate.net/publication/254006015_A_narrative_theory_of_games read here] “Interactive Fiction” by Anthony Niesz and Norman Holland, 1984 McKenzie Wark says (talking about capitalism) that if the word feels like it doesn't fit anymore then it's probably wrong. But putting the word 'narrative' beside 'games' for me gives two results: 'narrative games' and 'game narratives' (of course there are other variations with plurals and singulars, but I'll fo...") |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 70: | Line 70: | ||

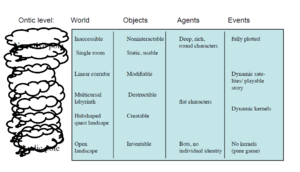

In the events section he presents story and game as opposite ends of a spectrum which seems completely unrelated to the rest of the essay. Also the diagram is titled discourse/infuence, in reference to the players influence over the kernel and sattelite narratives, this makes me even more confused about what he means by discourse. | In the events section he presents story and game as opposite ends of a spectrum which seems completely unrelated to the rest of the essay. Also the diagram is titled discourse/infuence, in reference to the players influence over the kernel and sattelite narratives, this makes me even more confused about what he means by discourse. | ||

[[File:Narrative-theory-of-games-model.png| | [[File:Narrative-theory-of-games-model.png|thumb|right|alt=Narrative theory of games model Espen Aarseth|Narrative theory of games model Espen Aarseth]] | ||

The model in section 9 has lots of useful words/categories in it, but the "narrative pole - ludic pole" axis in it is really not helpful. Luckily Microsoft Paint has a really useful tool for remixing ludonarrative diagrams so I have amended it. He then draws lines through the diagram representing different games, for example Minecraft apparently goes across the bottom of the graph as a "pure game". This really doesn't seem to match up with the more flexible theory presented earlier. In the 'objects' category this gives Minecraft only Inventable objects, while it in fact has all the types listed here, and the graph ignores how different types of object interact. I think he has done a good job of mapping the game space in this diagram but a bad job of charting how individual games move through this space like a discrete linear function, real games are much more interesting and messy than this. I dont think any of the conclusions in this section really follow from really good exploration of what a game is in previous sections. | The model in section 9 has lots of useful words/categories in it, but the "narrative pole - ludic pole" axis in it is really not helpful. Luckily Microsoft Paint has a really useful tool for remixing ludonarrative diagrams so I have amended it. He then draws lines through the diagram representing different games, for example Minecraft apparently goes across the bottom of the graph as a "pure game". This really doesn't seem to match up with the more flexible theory presented earlier. In the 'objects' category this gives Minecraft only Inventable objects, while it in fact has all the types listed here, and the graph ignores how different types of object interact. I think he has done a good job of mapping the game space in this diagram but a bad job of charting how individual games move through this space like a discrete linear function, real games are much more interesting and messy than this. I dont think any of the conclusions in this section really follow from really good exploration of what a game is in previous sections. | ||

Latest revision as of 19:07, 4 March 2023

“Interactive Fiction” by Anthony Niesz and Norman Holland, 1984

McKenzie Wark says (talking about capitalism) that if the word feels like it doesn't fit anymore then it's probably wrong. But putting the word 'narrative' beside 'games' for me gives two results: 'narrative games' and 'game narratives' (of course there are other variations with plurals and singulars, but I'll focus on these two for now).

The first, 'narrative games', is very clearly a category of computer games to me. Breath of the Wild is a narrative game, Worms is not. Things can be on the margin of the category (Is Pacman a narrative game? It has characters and a plot), and the category can be stretched and skewed to prove a point (all games are narrative games is really just word play) but in most cases it makes sense and is seful to say that some games contain narrative elements ('theoretical concepts such as “story”, “fiction”, “character,” “narration” or “rhetoric”') and those games can be referred to as 'narrative games'.

The second combination of the two words is 'game narratives' which again seems to refer to something internal to the game to me, for the moment ignoring more extended narratives of the game world like the story of Half-Life 3 or the Super Mario Bros Movie. Game narratives are the stories (fictions, characters, etc.) within a game. Narrative is an element or group of elements that are within games and can be used to examine certain aspects of them. What narratives are in Fortnite, where is the narrative in Minesweeper. As a characteristic, narrative is a way to look at games.

there is much to gain from a rigorous application of narratology to game studies

But also maybe the interesting thing about computer games is what is left in them after you describe the narrative elements, after you describe the ludic elements. Is there something unique to this medium? The feeling of exploring an open map, being able to fly, being able to skate, there is something about the immersion of a computer game that I don't think you get from other media. Not just immersion but powering-up, in music you can only tell me "Heaven is a Halfpipe" but in a computer game right now on earth I can do jack. There's no way I can know Ash Ketchum's struggle as much through the TV show or the card game as I can through playing his life on the GameBoy (although maybe the cards are not as well executed as the games or the show, but even if they were).

to emphasize the crucial importance of combining the mechanical and the semiotic aspects and to caution against and criticize the uncritical and unqualified application of terms such as “narrative” and “story” to games.

This does not feel like appropriate language to talk about games. I think Aarboy is trying to say something like "it's important to pay attention to the play part of gameplay as well as the stories in the game, because being a player makes you relate to the medium differently than a reader or viewer".

I wish to challenge the recurrent practice of applying the theories of literary criticism to a new empirical field, seemingly without any critical reassessment of the terms and concepts involved. (Aarseth 1997: 14)

The author of this essay has just quoted themself in the third person. Some readers may find this unusual (eg Stephen).

games and stories seem to share a number of elements, namely a world, its agents, objects and events.

Yessss and also (especially in the case of games, but this is useful for other stories) a range of possible actions in the world which are selected not just ideologically but for narrative purposes. Eg. why didnt the eagles fly to Mordor, and other "plotholes" which are choices not available in the narrative, actions you can't take in the game or areas you cant reach.

Whatever the answer, it seems clear that it is not purely a game, but a piece of software that does contain, among other things, a game.

Has anyone done a Clifford Geertz style analysis of games? A thick description, what are the players thinking, what are the game developers thinking, and also who else is involved in the game (the labourers who create and package it, the audience, are there NPC's ouside of the game?).

Ontic

Relating to entities and the facts about them; relating to real as opposed to phenomenal existence.

Multicursal

Of a maze or labyrinth: having more than one possible route between the centre and the outside.

My present approach is to see the ludo-narrative designspace as four independent, ontic dimensions: WORLD, OBJECTS, AGENTS, and EVENTS. Every game (and every story) contains these four elements, but they configure them differently

Yeah cool.

If an(y) interesting experience in a game is an “emergent narrative,” where does it end? And why limit this category to game-based situations? At some point it becomes hard to distinguish narratives from any other type of worldly experience

Well for me it probably ends where a narrative is something created (intentionally or otherwise) and this created story contains elements of the worldview of the creator(s) which it often (again intentionally or not) communicates to the narratee. This is probably not all worldly experience, relax, unless we are living in a simulation.

The story-telling model shown in section four really shows me how much of a traditional narrative model Espy is abandoning. All of his "ontic dimensions" fit into the category of Existents, except for Events, which is right beside them. These all fit in the "story" side of the "story-telling" model which leaves out all of the discourse elements, how the story is told. Hopefully he'll address these anyway.

A kernel is what makes us recognize the story... Satellites are what can be replaced or removed while still keeping the story recognizable, but which defines the discourse; replace the satellites and the discourse is changed.

Kernels/satellites is a nice idea, but Im not sure what EA means by discourse here. In the diagram he implied discourse is the unimportant half, and now he is relegating it to something that does not happen in the kernel of the story. It feels like he is saying there is some essential information in the main plot line that is the "point" of the story, which doesn't seem correct to me.

However, the world presented in a game is not necessarily a game world only. A game can contain two types of space, the ludic and the extra-ludic.

The difference between the playable, explorable 'gameworld' and the (usually larger) fictional world the game is set in.

In a previous paper (Aarseth 2005) I

This is the third time he has quoted himself, baller.

[Objects] are important because they determine the degree of player agency in the game: a game which allows great player freedom in creating or modifying objects will at the same time not be able to afford strong narrative control.

Probably true in most cases but this feels more like a correlation to me than the only cause. A player has agency based on the actions they can take more generally, what other agents can they interact with and how those interactions can play out, how can they explore the world in terms of speed and percieved freedom of movement, do events feel like they are happening to or caused by the player.

It can be claimed that the richness of character is an important authorial tool that characterizes the positive potential of authorship in games, where malleability and user control limit authorial affordances.

This does not fit with for example the characters of Sims, who can become extremely complex mostly due to the player, rather than the "author", assuming EA Games is referring to the game designer here. Unless he's talking about authorship in a more general sense of users creating meaning in which case I totally agree. Anyway yeah Sims, computer game as a toolset or dollhouse for exploring relationships according to the player's will rather than a novel with some exemplar relationships.

In the events section he presents story and game as opposite ends of a spectrum which seems completely unrelated to the rest of the essay. Also the diagram is titled discourse/infuence, in reference to the players influence over the kernel and sattelite narratives, this makes me even more confused about what he means by discourse.

The model in section 9 has lots of useful words/categories in it, but the "narrative pole - ludic pole" axis in it is really not helpful. Luckily Microsoft Paint has a really useful tool for remixing ludonarrative diagrams so I have amended it. He then draws lines through the diagram representing different games, for example Minecraft apparently goes across the bottom of the graph as a "pure game". This really doesn't seem to match up with the more flexible theory presented earlier. In the 'objects' category this gives Minecraft only Inventable objects, while it in fact has all the types listed here, and the graph ignores how different types of object interact. I think he has done a good job of mapping the game space in this diagram but a bad job of charting how individual games move through this space like a discrete linear function, real games are much more interesting and messy than this. I dont think any of the conclusions in this section really follow from really good exploration of what a game is in previous sections.