Media Object: Atlas, collecting the world: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| (57 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 15: | Line 15: | ||

[Under construction] <br><br> | [Under construction] <br><br> | ||

http://www.mediaartnet.org/assets/img/data/2968/full.jpg | http://www.mediaartnet.org/assets/img/data/2968/full.jpg<br> | ||

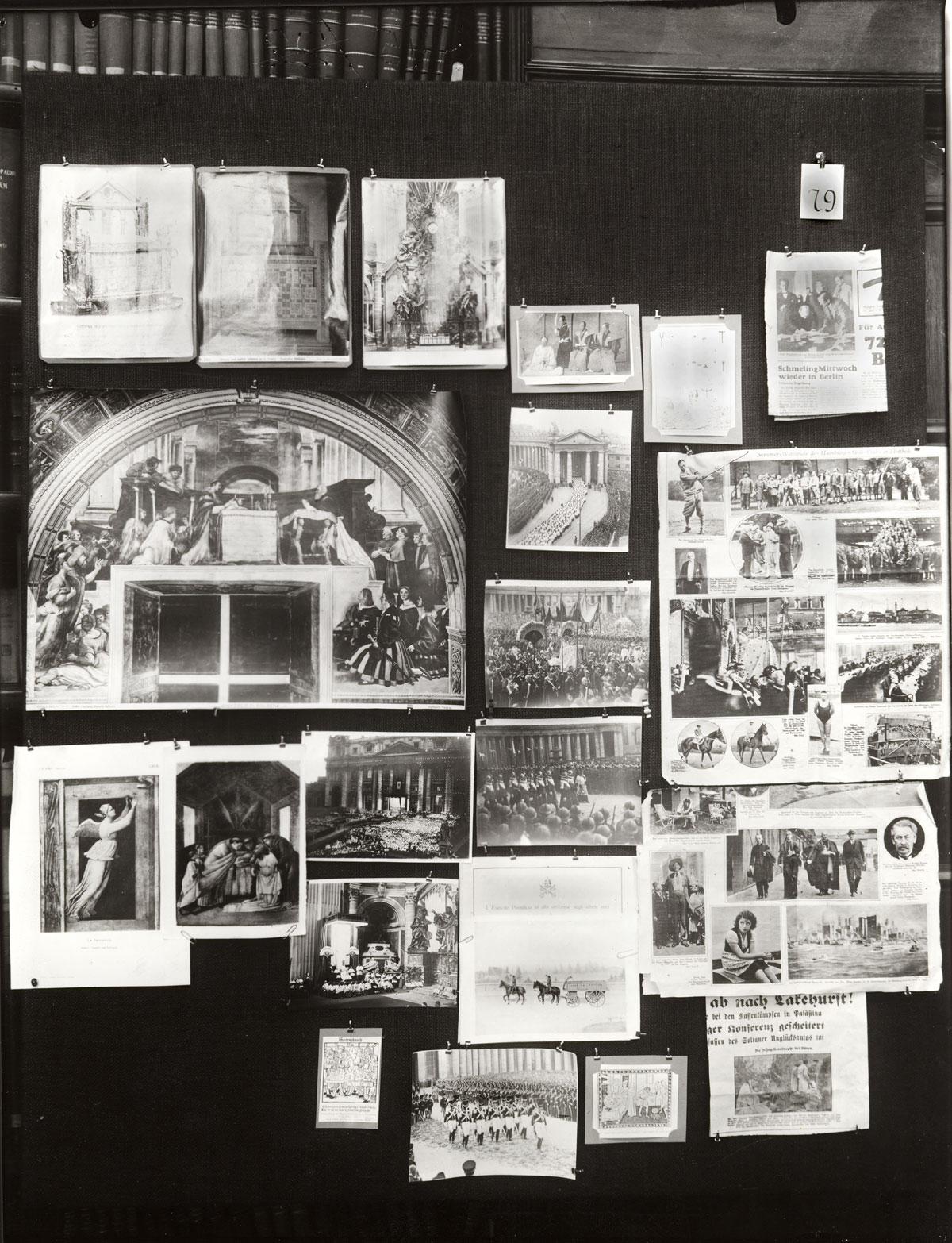

One of Warburg's ''Bilderatlas'' panels | |||

<br><br> | <br><br> | ||

== "Since Warburg’s work, not only has the atlas profoundly modified the forms – and therefore the content – of all ‘cultural sciences’ or human sciences, but it has also incited a great number of artists to completely rethink – as a collection and a re-montage, a piecing together – the modalities according to which the visual arts are elaborated and presented today." == | |||

(Didi-Huberman, p.18) | |||

<br><br> | |||

'''Introduction:''' <br> | |||

As a media object I choose the Atlas. One opens an Atlas to look for a specific piece of information but one can also ponder upon and scan through and let your imagination go. It is an object to contemplate upon, to gather new knowledge. An object that is ever-changing, never finished. Also an object that aims to collect and organize the world. More specifically I am interested in the Mnemosyne Atlas by Aby Warburg. Not only due it's art historical value and it's influence on artists, but also as a precursor of how we think about images. <br><br> | |||

Initially my interest in the atlas as an artistic object started while working on my series Sunstudies (2012/2013) and Lightstudies (2015/2016). The images are always presented in a grid, being heterogenious but still different. Both series deal with the notion of registering something that we can't see with our own eyes, like scientific imagery. In both series I used the camera as a tool to create images that are in a way still a direct vingerprint of our reality but through certain technical choices, as using a pinhole and/or a long shutter time, become so abstracted or unreal that they refer to nothing at all anymore. | |||

<br> <br> | |||

http://www.fabianlandewee.com/lightstudies_screenshot.jpg<br><br> | |||

Besides, the idea of an open ended ever changing collection of images that can be rearranged as several possibilities is important to my photographic work. Therefore my work should always be presented as a ‘table’ not as a ‘tableau’. The idea of the working table and the open possibility of changing the order of the images therefore also means that I do not work in fixed series or projects with my photographic images. Warburg's Atlas in that sense shows the same process. | |||

'''The Atlas''' <br> | |||

The Titan Atlas was condemned to carry the universe after the Titans lost the war (Titanomachy) to the Olympians. The universe is often often depicted as an orb showing information about cosmology and geography. Through carrying the sky, Atlas had the time to gather all that is to know about the earth and the sky, hence the name given to the book containing maps. The atlas in its geographical context was created in the late 16th century by Gerardus Mercator. For years after the atlas contained information about geography and cosmology. In the 19th century more categories were added, by then any information that could be systematically organized could be considered an atlas. | |||

Warburg's Atlas was radically different from the standard . As Didi-Huberman writes, Warburg's Atlas is not only a collection of images from one particular area of knowledge, but I quote ''"... these collections of images could just as easily have their roots in a dense web of thoughts, in a kind of non-systematic system out of which would emerge a complex fabric (or ‘text) woven out of various intellectual, spiritual and artistic phenomena.”'' (Didi-Huberman, p. 18). This dense web of thoughts did not only refer to Warburg’s Atlas. Through out the years Warburg collected around 60.000 books for his library which were not ordered alphabetically or in a certain timeline, but by theme and connection, the library turns into a ''Denkraum''. | |||

Warburg started assembling his ''Atlas'' in 1925 after being released from a Swiss psychiatric clinic. It consisted out of more than 60 black panels of each 170 by 140 cm and contained over 1000 images. The project was left unfinished in 1929 when Warburg unexpectedly died. He used metal clasps to arrange and rearrange the reproduced black and white photographs of art-historical and cosmographical images. Then he would photograph his arrangement before starting the rearrangement again. For creating his Atlas he used his own metonymic, intuitive logic, after all he had studied these images almost his whole life. | |||

Besides creating a Denkraum with his Atlas, Warburg's main aim was to outline the ''Nachleben'' of certain gestures and motives found in antiquity that reappear later in the Renaissance and later time periods. The term ''Nachleben'' somehow encapsulates that there are traces that remain over time, patterns that reemerge in different stages of culture. He called these gestures and motives ''pathos formula'' but Warburg"... ''more specifically argued that his attempt to construct collective historical memory would focus on the inextricable link between the mnemomnic and the traumatic."'''' (Buchloch, p.14). | |||

This focus on the mnemonic and traumatic is therefore probably the reason why Warburg's work was dubbed as the ''Mnemosyne Atlas''. Two mythological characters put together, Atlas as the symbol of knowledge and suffering (after all, he was punished to carry the universe on his back, but also became an all knowing character of all the secrets of the earth and the universe). Mnemosyne, the mother of the 9 muzes, was the titanes of memory. | |||

. | |||

If we look at the panels themselves.... | |||

"''While according to Warburg collective social memory could be traced through the various layers of cultural transmission (his primary focus being the transformation of <<dynamograms>> transferred from classical antiquity to Renaissance painting, the reoccuring motif of gesture and bodily expression that he had identified in his notorious term as <<pathos formulas>>), Warburg more specifically argued that his attempt to construct collective historical memory would focus on the inextricable link between the mnemomnic and the traumatic."'' (Buchloch, p.14). | |||

These dynamograms | |||

<br><br> | <br><br> | ||

<br> | |||

<br><br> | <br><br> | ||

| Line 39: | Line 81: | ||

''"But the Atlas, at least according to it's author's intentions, would also accomplish a materialist project of constructing so ial memory by collecting photographic reproductions of a broad variety of practices of representation. Warburg's Atlas thus not only reiterated first of all his life-long challenge to the rigorous and hierararchical compartmentalization of the discipline of art history, by attempting to abolish its methods and categories of exclusively formal or stylistic description. Yet by eroding the disciplinary boundaries between the conventions and the studies of high art and mass culture, the Atlas also questioned whether mnemonic experience could even be constructed any longer under the universal reign of photographic reproduction, establishing the theoretical and the presentational framework to probe the competence of the mnemonic from which Hoch's scrapbook would emerge a few years later."'' (Buchloch, p.15) | ''"But the Atlas, at least according to it's author's intentions, would also accomplish a materialist project of constructing so ial memory by collecting photographic reproductions of a broad variety of practices of representation. Warburg's Atlas thus not only reiterated first of all his life-long challenge to the rigorous and hierararchical compartmentalization of the discipline of art history, by attempting to abolish its methods and categories of exclusively formal or stylistic description. Yet by eroding the disciplinary boundaries between the conventions and the studies of high art and mass culture, the Atlas also questioned whether mnemonic experience could even be constructed any longer under the universal reign of photographic reproduction, establishing the theoretical and the presentational framework to probe the competence of the mnemonic from which Hoch's scrapbook would emerge a few years later."'' (Buchloch, p.15) | ||

| Line 58: | Line 97: | ||

Heuristic technique <br> | Heuristic technique <br> | ||

Knowledge as punishment<br> | Knowledge as punishment<br> | ||

dialectical images<br> | |||

Reaching totality through fragments <br> | Reaching totality through fragments <br> | ||

The idea of images as knowledge <br><br> | The idea of images as knowledge <br><br> | ||

Cultural vs. personal memory <> Warburgian unconsciousness <br><br> | Cultural vs. personal memory <> Warburgian unconsciousness <br><br> Cultural memory is not Jungian collective Unconscious????? <br> | ||

The dynamic that goes on between conscious and unconscious in creating the combination of images <br> | The dynamic that goes on between conscious and unconscious in creating the combination of images <br> | ||

A dance between the conscious and the unconscious <br> | A dance between the conscious and the unconscious <br> | ||

| Line 78: | Line 118: | ||

'''Bibliography:'''<br> | '''Bibliography:'''<br> | ||

G. Didi-Huberman (2010), Atlas: How to Carry the World on One's Back?, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte <br> | G. Didi-Huberman (2010), Atlas: How to Carry the World on One's Back?, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte <br> | ||

https://www.groene.nl/artikel/op-zoek-naar-de-ziel-van-de-westerse-cultuur<br> | https://www.groene.nl/artikel/op-zoek-naar-de-ziel-van-de-westerse-cultuur<br> | ||

{{#widget:Vimeo|id=24023841}}<br> | {{#widget:Vimeo|id=24023841}}<br> | ||

{{#widget:YouTube|id=UO7FlZ9Gikw}} | {{#widget:YouTube|id=UO7FlZ9Gikw}} | ||

<br><br> | |||

To view some panels: https://warburg.library.cornell.edu/panel/b | |||

Latest revision as of 11:26, 20 June 2017

[Under construction]

One of Warburg's Bilderatlas panels

"Since Warburg’s work, not only has the atlas profoundly modified the forms – and therefore the content – of all ‘cultural sciences’ or human sciences, but it has also incited a great number of artists to completely rethink – as a collection and a re-montage, a piecing together – the modalities according to which the visual arts are elaborated and presented today."

(Didi-Huberman, p.18)

Introduction:

As a media object I choose the Atlas. One opens an Atlas to look for a specific piece of information but one can also ponder upon and scan through and let your imagination go. It is an object to contemplate upon, to gather new knowledge. An object that is ever-changing, never finished. Also an object that aims to collect and organize the world. More specifically I am interested in the Mnemosyne Atlas by Aby Warburg. Not only due it's art historical value and it's influence on artists, but also as a precursor of how we think about images.

Initially my interest in the atlas as an artistic object started while working on my series Sunstudies (2012/2013) and Lightstudies (2015/2016). The images are always presented in a grid, being heterogenious but still different. Both series deal with the notion of registering something that we can't see with our own eyes, like scientific imagery. In both series I used the camera as a tool to create images that are in a way still a direct vingerprint of our reality but through certain technical choices, as using a pinhole and/or a long shutter time, become so abstracted or unreal that they refer to nothing at all anymore.

Besides, the idea of an open ended ever changing collection of images that can be rearranged as several possibilities is important to my photographic work. Therefore my work should always be presented as a ‘table’ not as a ‘tableau’. The idea of the working table and the open possibility of changing the order of the images therefore also means that I do not work in fixed series or projects with my photographic images. Warburg's Atlas in that sense shows the same process.

The Atlas

The Titan Atlas was condemned to carry the universe after the Titans lost the war (Titanomachy) to the Olympians. The universe is often often depicted as an orb showing information about cosmology and geography. Through carrying the sky, Atlas had the time to gather all that is to know about the earth and the sky, hence the name given to the book containing maps. The atlas in its geographical context was created in the late 16th century by Gerardus Mercator. For years after the atlas contained information about geography and cosmology. In the 19th century more categories were added, by then any information that could be systematically organized could be considered an atlas.

Warburg's Atlas was radically different from the standard . As Didi-Huberman writes, Warburg's Atlas is not only a collection of images from one particular area of knowledge, but I quote "... these collections of images could just as easily have their roots in a dense web of thoughts, in a kind of non-systematic system out of which would emerge a complex fabric (or ‘text) woven out of various intellectual, spiritual and artistic phenomena.” (Didi-Huberman, p. 18). This dense web of thoughts did not only refer to Warburg’s Atlas. Through out the years Warburg collected around 60.000 books for his library which were not ordered alphabetically or in a certain timeline, but by theme and connection, the library turns into a Denkraum.

Warburg started assembling his Atlas in 1925 after being released from a Swiss psychiatric clinic. It consisted out of more than 60 black panels of each 170 by 140 cm and contained over 1000 images. The project was left unfinished in 1929 when Warburg unexpectedly died. He used metal clasps to arrange and rearrange the reproduced black and white photographs of art-historical and cosmographical images. Then he would photograph his arrangement before starting the rearrangement again. For creating his Atlas he used his own metonymic, intuitive logic, after all he had studied these images almost his whole life.

Besides creating a Denkraum with his Atlas, Warburg's main aim was to outline the Nachleben of certain gestures and motives found in antiquity that reappear later in the Renaissance and later time periods. The term Nachleben somehow encapsulates that there are traces that remain over time, patterns that reemerge in different stages of culture. He called these gestures and motives pathos formula but Warburg"... more specifically argued that his attempt to construct collective historical memory would focus on the inextricable link between the mnemomnic and the traumatic."'' (Buchloch, p.14).

This focus on the mnemonic and traumatic is therefore probably the reason why Warburg's work was dubbed as the Mnemosyne Atlas. Two mythological characters put together, Atlas as the symbol of knowledge and suffering (after all, he was punished to carry the universe on his back, but also became an all knowing character of all the secrets of the earth and the universe). Mnemosyne, the mother of the 9 muzes, was the titanes of memory. . If we look at the panels themselves....

"While according to Warburg collective social memory could be traced through the various layers of cultural transmission (his primary focus being the transformation of <<dynamograms>> transferred from classical antiquity to Renaissance painting, the reoccuring motif of gesture and bodily expression that he had identified in his notorious term as <<pathos formulas>>), Warburg more specifically argued that his attempt to construct collective historical memory would focus on the inextricable link between the mnemomnic and the traumatic." (Buchloch, p.14).

These dynamograms

"According to his aspirations as recorded in the diaries, the Mnemosyne Atlas sought to construct a model of the mnemonic in which Western European humanist thought would once more, perhaps for the last time, recognize its origins and trace its latent continuities into the present, ranging spatially across the confines of European humanist culture and situating itself temporally within the paramets of European history from classical antiquity to the present." (Buchloch, p. 14)

"While according to Warburg collective social memory could be traced through the various layers of cultural transmission (his primary focus being the transformation of <<dynamograms>> transferred from classical antiquity to Renaissance painting, the reoccuring motif of gesture and bodily expression that he had identified in his notorious term as <<pathos formulas>>), Warburg more specifically argued that his attempt to construct collective historical memory would focus on the inextricable link betweeen the mnemomnic and the traumatic." (Buchloch, p.14).

"But the Atlas, at least according to it's author's intentions, would also accomplish a materialist project of constructing so ial memory by collecting photographic reproductions of a broad variety of practices of representation. Warburg's Atlas thus not only reiterated first of all his life-long challenge to the rigorous and hierararchical compartmentalization of the discipline of art history, by attempting to abolish its methods and categories of exclusively formal or stylistic description. Yet by eroding the disciplinary boundaries between the conventions and the studies of high art and mass culture, the Atlas also questioned whether mnemonic experience could even be constructed any longer under the universal reign of photographic reproduction, establishing the theoretical and the presentational framework to probe the competence of the mnemonic from which Hoch's scrapbook would emerge a few years later." (Buchloch, p.15)

Farnese Atlas & August Sander, Arbeiter

“One can add that, on Atlas’ shoulders, the celestial sphere offered him the possibility of a real tragic knowledge, knowledge through contact and pain: everything he knew about the cosmos he gained from his own misfortune and his own punishment. A close knowledge but an impure knowledge for that reason: an anxious and even ‘grivous knowledge if we take the expression that Homer uses in the Odyssey literally, to characterize Atlas: “the malevolent Atlas’ he says, using the formulation oloophron (from the adjective loose, meaning ‘harmful’), and who yet ‘knows the depths of all the seas and supports the great columns that hold earth and sky apart’. Atlas would therefore protect us, with his bodily strength, rom the sky crushing the earth. But, with his spiritual strength, he is as knowledgeable of the abysses as he is of the great cosmic intervals: he is the holder, therefore, of an abyssal knowledge that is as worrying as it is necessary, as ‘harmful’ as is it fundamental."

Keywords: tables instead of tableau's

Warburg: new model of time: concept of nachleben = that there is something that remains over time, maybe is updated in different times and cultures, these patterns that reemerge in different stage of culture, something to do with memory. Traces are made after an experience and somehow memory is very dynamic, it can be updated, there are new associations of traces, and Nachleben is a concept that has a resonance with some neurobiological aspects of memory. There are traces that are reupdated, that are reassociated with time. This works as a model, but not in practice to explain the "Warburgian unconsciousness"

Heuristic technique

Knowledge as punishment

dialectical images

Reaching totality through fragments

The idea of images as knowledge

Cultural vs. personal memory <> Warburgian unconsciousness

Cultural memory is not Jungian collective Unconscious?????

The dynamic that goes on between conscious and unconscious in creating the combination of images

A dance between the conscious and the unconscious

Visual cortex sensitive to angles and lines and contrast etc.

Conscious creation of distance > the means which by he moves from the demonic towards the estatic

Nietzsche polarity < dionysian <> Apolian

To de-demonize these images, but also his own past

Hannah Hoch scrapbook <> Tumblr

Bibliography:

G. Didi-Huberman (2010), Atlas: How to Carry the World on One's Back?, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte

https://www.groene.nl/artikel/op-zoek-naar-de-ziel-van-de-westerse-cultuur

To view some panels: https://warburg.library.cornell.edu/panel/b