User:Chen Junyu/Graduation Project Seminar/ project proposal/Proposal6: Difference between revisions

Chen Junyu (talk | contribs) |

Chen Junyu (talk | contribs) |

||

| (3 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 7: | Line 7: | ||

</small>''' | </small>''' | ||

In the Asiatic world, belief in the supernatural power of the artist remained alive over greatly prolonged period. And there was no absolute division between magic, religion and philosophy in the east, especially in China. Taoism, as the primitive Chinese philosophy | In the Asiatic world, belief in the supernatural power of the artist remained alive over greatly prolonged period. And there was no absolute division between magic, religion and philosophy in the east, especially in China. Taoism, as the primitive Chinese philosophy, effects the developing of Chinese painting on a fundamental base. It influences the establishment of the material system and the construction of the painting principles. | ||

The generally accepted principle for Chinese painting was written by Hsieh Ho,a writer, art historian and critic in 6th century China, named as ''The Six Principles of Hsieh Ho''. He summarized six sentences to divide the different level of paintings. There are different versions of the interpretation in English of the six principles, and all of them are so contrasting, here I use the translation of Osvald Siren's ''Early Chinese Painting'', which I think it is the closest one to the original version. | The generally accepted principle for Chinese painting was written by Hsieh Ho,a writer, art historian and critic in 6th century China, named as ''The Six Principles of Hsieh Ho''. He summarized six sentences to divide the different level of paintings. There are different versions of the interpretation in English of the six principles, and all of them are so contrasting, here I use the translation of Osvald Siren's ''Early Chinese Painting'', which I think it is the closest one to the original version. | ||

| Line 51: | Line 51: | ||

And Michael Sullivan gives a brief tour of comparisons toward the end of his book The Meeting of Eastern and Western Art (1989), he says the “aims and techniques of the Cubists were, to some extent, anticipated by the Chinese landscape painter Wang Yuanqi 王原祁 (1642– 1715).” Both Wang and Cézanne had a method of “pulling ... mountains and rocks apart and reassembling them into a tightly organized mass,” and both worked with a kind of “laborious intensity.” | And Michael Sullivan gives a brief tour of comparisons toward the end of his book The Meeting of Eastern and Western Art (1989), he says the “aims and techniques of the Cubists were, to some extent, anticipated by the Chinese landscape painter Wang Yuanqi 王原祁 (1642– 1715).” Both Wang and Cézanne had a method of “pulling ... mountains and rocks apart and reassembling them into a tightly organized mass,” and both worked with a kind of “laborious intensity.” | ||

[[File:1510957674983476622.jpg| | [[File:1510957674983476622.jpg|100px|thumbnail]] | ||

'''Connecting to Mondrian''' | |||

'''Connecting to | |||

==Literature Survey== | ==Literature Survey== | ||

Latest revision as of 21:06, 26 January 2015

Question

By which way, I could approach the core in my work that Chinese painting always chases for--resonance of the spirit,movement of life.

Context

Here is a story about the great Chinese painter Zhang Sengyou (Chinese: 张僧繇). Quoted from Fritz Van Briessen's The Way of the Brush, originally written by Zhang Yanyuan from Tang Dynasty:

Zhang one day decided to paint a dragon on the wall of his house. He guided his brush with full confidence, and after a while the dragon was finished except for its eyes. Suddenly the master's courage failed him. He simply did not dare to paint those eyes. When, many months later, he at last felt brave enough, he groped for his brush and with swift strokes dashed in eye and pupil. Within an instant the dragon broke into cloud roaring and flew away, leaving a trace of fire and smoke.

In the Asiatic world, belief in the supernatural power of the artist remained alive over greatly prolonged period. And there was no absolute division between magic, religion and philosophy in the east, especially in China. Taoism, as the primitive Chinese philosophy, effects the developing of Chinese painting on a fundamental base. It influences the establishment of the material system and the construction of the painting principles.

The generally accepted principle for Chinese painting was written by Hsieh Ho,a writer, art historian and critic in 6th century China, named as The Six Principles of Hsieh Ho. He summarized six sentences to divide the different level of paintings. There are different versions of the interpretation in English of the six principles, and all of them are so contrasting, here I use the translation of Osvald Siren's Early Chinese Painting, which I think it is the closest one to the original version.

The six principles of Chinese painting:

1) Resonance of the spirit; Movement of Life.

2) Bone Manner (i.e. Structural) Use of the Brush.

3) Conform with the objects ( to obtain ) their Likeness.

4) According to the Species, apply the Colours.

5) Plan and Design; Place and Position ( Composition)

6) To transmit Models by Drawing.

In Hsieh Ho's principles, the achievement of resonance of the spirit/movement of life is the standard that if a painting reaches the highest level. The transmition of model by drawing is the requirement for the lowest level of Chinese painting. That is to say, the representational depiction in Chinese painting is not the most important factor, it can be the provement of the painter's technique. Only when a painting transmit the lively spirtual of what the painter wants to express, the authenticity behind the surface,this painting can be judged as one of the best category.

The Abstraction of Chinese landscape painting and the possible relation with Dutch( Western) painting

From Modrian to American exprssion, abstraction art has near 100 years history. But since 4th century, there has already existed abstraction in Chinese painting - it is not purely formalism as neoplasticism, the figure of object is still depicted in the painting. From that time, some painters started pursuing the expression of their feeling and spirit by the changing of the usage of the ink and brush. More or less at the same time, Hiesh Ho proposed his six principle of Chinese painting to define the importance of expression of spirit and vitality. His idea of how to consider when judging a painting also suggests the importance of expressing the invisible real existence behind the object in Chinese painting.

Chinese landscape painting can be traced to Jin Dynasty(3th to 4th century), it is the time which has the most free spirit and liberative mind. Zong Baihua, the 20th centuries art critic and theorist mentions in his article Thoughts of <A New Account of the Tales of the World> and the beauty of Jin Dynasty "People in Jin saw clearly the nature outward and the humans inward". The landscape, and all the other types of Chinese painting, is a combination of the description of the physical world and the feelings or understanding of humanity. We can say the Chinese painting already reaches a peak during Jin. But, since the lack of strict logical structure and theory in representing the combination of physics and mind( the way that can be spoken of, is not the constant way -- Laozi), also because the achievement of Jin relates to the complex culture and politics background, the descendants can never copy their artistic accomplishment. I think because of the unachievable accomplishment,make Jin's art works become the standard all the others.

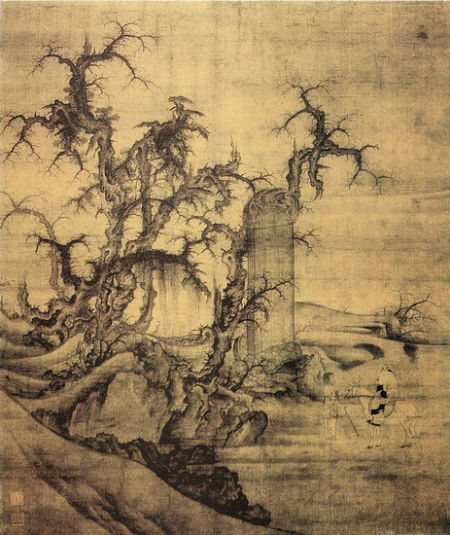

Comparison: I agree with James Elkins says in his book "Chinese Landscape painting in Western Art Theory", Of all cross-cultural descriptions, comparisons seem especially fraught. Outright comparisons can appear rude (are the Han Dynasty or the Yuan really akin to Western modernism, as both have been claimed to be?) but qualified, introductory, or otherwise informal comparisons can seem both appropriate and useful. Because the different culture background sometimes misunderstand spectator for the purpose of the painter. For example in the book of Benjamin Rowland "Art in East and West, An introduction through comparison" , he compares a detail of Matthias Grünewald’s The Temptation of St. Anthony with a painting attributed to Li Cheng 李成 called Reading the Tablet, in order to show how “demon groves” are a theme in China and in the West.

Quoted from James' book: Rowland “Li Cheng’s painting “represents a traveler seated on a donkey, scrutinizing with fearful intensity the inscription on a stele that rises like a menhir before a grotesque group of pine trees that arch their dragon branches against the empty sky.” Rowland is hypnotized by the “concentration and isolation of the twisted trees with their tortuous, iron-hard trunks and crab-claw branches,” and he finds the same “sinister” mood in The Temptation of St. Anthony, where “all nature, dreadful and deformed, enters into the demoniacal conspiracy against St. Anthony.” The branch Rowland excerpts is an icon of evil: it “stretches its dead, moss-covered branches in a kind of malediction over the ampitheater of monstrosities.” Then he mentions, Richard Barnhart has written an excellent short essay on the meaning of old trees in Chinese painting: they have more to do with longevity and independence than evil.

But some comparison in <Art in East and West> is nearly perfect. Such as the comparison between Friedrich and Ma Yuan. This comparison focuses more on the atmosphere which the paintings transmit.

And Michael Sullivan gives a brief tour of comparisons toward the end of his book The Meeting of Eastern and Western Art (1989), he says the “aims and techniques of the Cubists were, to some extent, anticipated by the Chinese landscape painter Wang Yuanqi 王原祁 (1642– 1715).” Both Wang and Cézanne had a method of “pulling ... mountains and rocks apart and reassembling them into a tightly organized mass,” and both worked with a kind of “laborious intensity.”

Connecting to Mondrian

Literature Survey

Philip Rawson, Drawing

Fritz van Briessen The Way of the Brush: Painting Techniques of China and Japan

James Elkins, Chinese Landscape Painting as Western Art History

Xie He Six principles of Chinese painting 古画品录

Lu Hong, The Formation and Development of New Ink Art in China http://www.mplusmatters.hk/inkart/paper_topic2.php?l=en

Zhu Qi, "Natural and abstract form and the unfinished modernism of Chinese painting" http://www.artlinkart.com/cn/article/overview/b55cvCso

Zong baihua,"Thoughts of <A New Account of the Tales of the World> and the beauty of Jin Dynasty"