User:Eleanorg/2.1/gradProposal1: Difference between revisions

| (78 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

== General Introduction == | == General Introduction == | ||

I am | <div style="background-color:#eee;padding:30px;"> | ||

<span style="font-style:italic;font-size:16px;"> | |||

"If I am struggling for autonomy, do I not need to be struggling for something else as well, a conception of myself as invariably in community, impressed upon by others[?]" | |||

</span> <br /><br > | |||

<span style="text-align:right;"> | |||

(Butler 2004, p.21). | |||

</span> | |||

</div> | |||

I will be creating a collaborative online publishing tool. It will invite participants to produce a publication about consent, in a way which encourages self-awareness about the dilemmas and compromises of working together consensually. The project will use networked publishing and web-to-print tools in order to do this. It will be situated within current feminist debates surrounding consent, as a microcosm of wider discussions of how we are to live democratically together. | |||

==Social Context: The Feminist "Consent" Debate== | |||

<div style="background-color:#eee;padding:10px;"> | |||

<span style="font-style:italic;"> | |||

"The issue of 'consent'... is about more than the letter of the law, and, like all sexual issues, at its heart is communication." | |||

</span> <br /><br > | |||

<span style="text-align:right;"> | |||

(Kramer Bussel 2008, p.43) | |||

</span> | |||

</div> | |||

<em></em><br /> | |||

The questions of how people negotiate consensually, and what it means to do this, have long been a fascination in my work and activism. It is widely held that governments derive legitimacy from "the consent of the governed" (Johnston 2010), and many leftwing groups take this idea to its logical conclusion in their use of Consensus decision-making. Consensus means "looking for 'win-win' solutions [in which] everyone agrees with the final decision" (Seeds for Change, 2012a). However, a closer look at what it means to "consent" poses challenges to this ideal. Under what conditions do we consent, and is consenting the same as really endorsing something? Can and should we consent out of solidarity to something we do not want? One field which is actively posing these questions is the feminist anti-rape movement, in which I have been active for several years and for which "consent" is of central concern. This field has interesting contributions to make to broader debates about how we are to live democratically together. | |||

The anti-rape movement makes frequent reference to "consent" as the vital missing ingredient in abusive encounters. (As legal theorists put it, consent works a "moral magic", which makes otherwise impermissable acts permissable (Kleinig, 2010)). It thus campiagns tirelessly under the banner "No Means No", stressing that explicit consent - "saying yes" (Reclaim the Night Oxford, 2011)- should be sought, communicated and respected. (For further examples of this approach see Rape Crisis Scotland 2008, 2010 & 2011.) | |||

This discourse paints a black and white picture: either consent is given, or it is not, and only the most explicit of gestures ("saying yes") counts as valid consent. Ensuring that sexual subjects, as one government campaign put it, "get a 'yes' before sex" (Home Office, 2006) appears at first glance to be the highest goal of this movement. Its demands map closely onto dominant legal conceptions of consent as something which is sought by an active party, and either given or withheld by a reactive other (Kleinig, 2010). | |||

However, there is a growing call from within the feminist movement to expand the definition of valid consent from simply "saying yes", to a broader one including the process of negotiation itself. This trend is summed up in the title of Schwyzer's (2008) article, "The Opposite of Rape is not Consent: The Opposite of Rape is Enthusiasm". Schwyzer debunks the claim that "yes means yes", noting the vital distinction between giving consent and actually wanting something. Other feminist writers attempt to bridge this distinction by re-defining consent entirely. Proposals for a new definition have included "an active collaboration for the benefit... of all persons concerned" (Easton & Liszt, 1997), "an open dialogue" (Kramer Bussel, 2008), and a "process" based on "affirmative participation" (Millar, 2008). | |||

This debate about how exactly we should define consent is still emerging, and can be brought into fruitful dialogue with the question of how we might use networked media to collaborate in a democratic manner. These feminist models make vital distinctions between wanting something, endorsing something, and cooperating with something. Applied to democratic processes, they make clear that people who vote for something (even in a Consensus system) may not actually want it. This raises difficult and relevant questions for networked collaboration, asking how and why we cooperate with others. | |||

By chosing this social context I aim to work with people who are already familiar with debates surrounding "consent", in order to facilitate a process of teasing out some of the dilemmas and contradictions that it throws up. I will treat this specific context as a microcosm, with potentially useful contributions to wider debates about how we are to co-exist consensually (ie, democratically) as people. The field of feminist activism is an ideal setting in which to make these links between interpersonal consent and democratic consent more generally, as an activist movement by definition is faced not only with questions of "consent" as discussed above, but with the practical question of how to agree and act together as a movement of many individuals and groups. So, the primary audience and participants in the project will be those active in this feminist community. The secondary audience will be those interested in how the project's processes and outcomes contribute to discussions about consensual relations more broadly. | |||

== | ==Relation to previous work== | ||

[[File:playfight.pdf | thumb | 300px | Fig. 1: 'Play!Fight!' front cover]] | |||

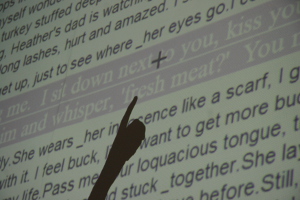

[[File:openSauce.jpg | thumb | 300px | Fig. 2: 'Open Sauce': installation view of track changes interface]] | |||

'' | [[File:dissoluteImageInstallationView2.jpg | thumb | 300px | Fig. 3: 'The Dissolute Image': installation view]] | ||

[[File:petraPortraitSmall.JPG | thumb | 300px | Fig. 4: 'Volunteer Hosts': volunteers agreed to 'host' files on their person over a set period of time]] | |||

[[File:ScrapedPlacards1.jpg | thumb | 300px | Fig. 5: A placard generated automatically from leftwing headlines]] | |||

This project continues a practice which self-reflexively analyses the way that groups organize. I take as subject, audience and participants those whose intention is to critique the non-consensual or undemocratic organization of society as it stands, and investigate how these groups organize in practice. In 2010 I set up the online platform Radical X to this end, which facilitates dialogue-based projects within activist communities: precisely those groups wrestling with what it means to consent, how far solidarity should extend, and how we might work together to articulate a shared vision. It has invited both bridge-building between apparently hostile communities (in the conversation and publishing project Play!Fight!, 2010), and highlighting of disagreements between those who seem to share common ground (in the collaborative writing project Open Sauce, 2011). Both these projects used debates about sexual politics as a "way in" to broader questions about how we negotiate the compromises inherent in interpersonal relations and democracy. It was important to both projects that the subject matter was embedded in the process of the projects themselves: a project about a clash of cultures set up and analysed this clash (by, for example, inviting speakers from one community into a physical space organized by another); a project about how fantasies are formed created a tool through which this process could happen and be analyzed (by using an open-access wiki for collaborative writing). | |||

Given the importance of investigating the subject of democratic negotiation <em>through</em> democratic processes, it became problematic that my role as facilitator involved a strong element of hierarchical curation (for example, chosing which texts to include in the end publication of Play!Fight!). | |||

'Open Sauce' (2011, Fig.2) began experimenting with handing over curation to the project's participants. In fact, observing the way in which participants edited each others' work became the most interesting aspect of the project. A developing fascination here was in the power of the editor/curator either to promote or to erase the words of others. I was fascinated by observing how this power is exercised. | |||

My interest in the conflicting desires to echo and to erase others' views was continued in 'The Dissolute Image' (2012, Fig.3), which confronted participants more directly with the question of whether they would enable the distribution of other people's (possibly objectionable) content. An image which had been censored from Facebook was divided into its individual pixels, with each one offered up for 'adoption' on participants' own websites. Only when all 95,000 pixels have been 'adopted' (posted on participants' own sites) will the image fully reappear. The vulnerability of digital files to their need for physical storage was also highlighted in the related project 'Volunteer Hosts' (2012, Fig.4), in which volunteers agreed to store a digital file about their person without knowing in advance what it contained. | |||

This project will bring the above explorations of what it might mean to 'facilitate' or 'transmit' back to the Radical X platform and its concern with sexual politics. Just as the question for feminists is, "is consenting to somthing the same as wanting it?", the question explored in the above projects is, "is hosting or transmitting something the same as endorsing it?". The project will develop processes for collaborative production which look critically at the role of those who transmit, publish or filter the works of others. The theme of "consent" will bring focus to this process, exploring (and embodying) questions such as: what does it mean to agree? What does it mean to endorse? And how far should cooperation with our allies extend? | |||

In order to do this, the project will look for technical models which enable the decentralization of curation/publishing of documents, so that participants can be confronted directly with these questions (rather than having them resolved through centralized curation). | |||

==Technical Tools and Context== | |||

'The Dissolute Image' and 'Volunteer Hosts' both stressed the reliance of digital documents on those who host or transmit them. This research responds to the wider context in which online publishing has radically changed what it means to publish a cultural object, and what the nature of that object is. No longer singular and stable, networked documents are vulnerable to others with which they are linked. (For example: dynamic websites break when an API is changed; images embedded from other servers can disappear; RSS feeds fill sites with unpredictable external content.) This has brought with it an exciting uncertainty about the status of the singular, autonomous agent (author) who creates and controls a discrete document. I have argued elsewhere that this brings tremendous opportunity for less defensive forms of sociality, while also posing frightening threats to our belief in an autonomous individual self. There are rich links to be made here with the debates about negotiation and consent discussed above, which deal with how and why we cooperate with others. The field of digital publishing, then, is an ideal technical context and starting-point. | |||

While the 'porous' nature of digital documents has tremendous social potential, the "atomization of content" (Ludovico, 2012) which it creates tends currently to serve quite different ends. As Ludovico, Parisier (2011) and IMC London (2012) point out, the devolution of curatorial power to individual users is currently more likely to create a personalized "filter bubble" than to expose readers to a broad range of challenging content. Those who helped to articulate this problem are turning back to paternalistic curation as a solution (Parisier & Peter Koechley's new anti-filter bubble service is "starting out with a heavy focus on curation — finding and sharing the best important stuff that the Internet generates each day" (Upworthy, 2012)). Others, such as outgoing Indymedia collective IMC London, express the vague and unmet need for "curation from within the sea of content" which "foster[s] true collaboration and solidarity" (IMC London 2012). | |||

What kinds of digital publishing tools could enable such a process, which does not resort to centralized curation but encourages the kind of dialogue-based collaboration envisioned by the feminist writers discussed above? | |||

===Wikis=== | |||

My first experiment with collaborative publishing ('Open Sauce') used a wiki, which enables multiple versions of a text to be saved on top of one another by many different writers. This worked for raising the question of whether to cooperate or compete (without centralized curation), as any participant could erase words in a previous version or keep them intact. However, the easy ability to delete disliked text didn't challenge participants as much as it might have done with the responsibility of leaving words intact which they disagreed with. Also, as the wiki was a single central site, participants weren't challenged with the question of whether they would publish the text themselves. The singular, chronological form of a wiki lends itself to the idea that a text is to be 'improved' - rather than a model of possibily overlapping, provisional collections of texts (as per the consent model) which are not striving chronologically towards a united idea of 'truth' or 'quality'. | |||

===Embedding=== | |||

The use of image embedding (displaying an image on a webpage by linking to the file on another site) is another technology I've explored. In 'The Dissolute Image' and more recent prototypes using image embedding, participants are challenged more explicitly to display content from external sites which they don't control. This gets closer to my interests than the use of wikis, with their focus on altering the content provided by others. Embedding is limited, however, by its unsuitability for content other than image and video, and by the fact that links are only one-way: there is no way to keep track of who is participating. | |||

===Web scraping=== | |||

Web scraping - the automated extraction of content from a website for use elsewhere - is in some ways more sophisticated than embedding. I used it for a recent prototype which questions what it means to endorse a slogan, by generating placards automatically from online socialist headlines (Fig. 5). Unlike embedding, scraping allows for text content to be found and manipulated. However, specific types of content have to be searched for by a piece of software, taking away the simplicity found in simply embedding an image file, and thus making it harder to participate. It is also unclear how a project using web scraping would be able to coordinate or keep track of participants. It could be used to raise interesting questions about consent, however, as it is usually employed to extract information without permission from a site owner. | |||

===Peer to Peer filesharing=== | |||

Having explored the technologies above, my next step will be to better understand peer to peer models of circulating content. I will be looking for what these models have to offer in terms of circulation of files without centralized control, and the use of indexes or trackers to coordinate a horizontal group of participants. | |||

===Collaborative Authoring Tools & Web-to-Print=== | |||

Software which converts online files to print-ready documents has exciting potential to produce a physical outcome from a deliberative, online process of writing. I will be researching tools such as Booki, looking at how their conversion of online to paper content could be applied to a tool which encourages the type of social encounters described above. [[GIT]] | |||

By better understanding these models, I aim to revisit the technologies above and incorporate them into a publishing tool which: | |||

* Enables the contribution of content by participants | |||

* Enables the publishing or circulation of that content by other participants | |||

* Challenges participants to re-circulate content they may disagree with | |||

* Blurs the clear lines between different authors and their opinions | |||

* Allows participants to create physical documents (for example, magazines or flyers) from this online content. | |||

==Next Steps== | |||

This project has two practical aspects: a social one, and a technological one. | |||

The social aspect of the project will involve making links with people and groups in the community described above. This means meeting with people immersed in debates about consent, and finding out in more detail what dilemmas and questions arise for them from this field of activism. It will also involve finding out where points of intervention in this field might be (whether this is particular publications, events, or discussions) and what forms that intervention should take in order to respond in a relevant, comprehensible way. | |||

The technological aspect will be developed alongside this, looking for technologies which fulfil the requirements emerging from the social context. It will involve better understanding the technologies mentioned above (peer to peer models, collaborative authoring and web-to-print tools), and experimenting with how these can be used and/or re-purposed to create a custom puslishing tool. After developing initial prototypes I hope to participate in the 'Post-Digital' print lab proposed by Florian Cramer at Transmediale 2013, in order to experiment in a hands-on way with how these technologies could be used to produce physical documents through a deliberate social process. | |||

==Bibliography== | |||

===Publishing=== | |||

* Ludovico, Alessandro (2012) Post Digital Print: The Mutation of Publishing since 1894 (Eindhoven: Onopatopee). | |||

* Garsiel, Tali (2011) How Browsers Work: Behind the Scenes of Modern Web Browsers [online]. Accessed 19 October 2012 at http://taligarsiel.com/Projects/howbrowserswork1.htm. | |||

* IMC London (2012) Time to move on: IMC London signing off [online]. Accessed 13 October 2012 at http://london.indymedia.org/articles/13128 | |||

* Pariser, E. (2011) The Filter Bubble: How the New Personalized Web Is Changing What We Read and How We Think (London: Penguin). | |||

* Upworthy (2012) Could This Be The Most Upworthy Site In The History Of The Internet? [online]. Available at: http://www.upworthy.com/could-this-be-the-most-upworthy-site-in-the-history-of-the-internet (Accessed 1 December 2012). | |||

===Consent=== | |||

* Butler, J. (2004) 'Beside Oneself: On the Limits of Sexual Autonomy' in Undoing Gender (London: Routledge). | |||

* Easton, D. & Liszt, C. A. (1997) The Ethical Slut: A Guide to Infinite Sexual Possibilities (Oregon: Greenery Press). | |||

* Home Office (2006) If You Don't Get a 'Yes' Before Sex, Who'll Be Your Next Sleeping Partner? [campaign] PDF available at: http://www.homeoffice.gov.uk/documents/consent-campaign/Prison.pdf?view=... (Accessed 1 December 2012). | |||

* Johnston, J. (2010) 'A History of Consent in Western Thought', in: Miller, G. & Wertheimer, A. (eds.)(2010) The Ethics of Consent: Theory and Practice (Oxford: Oxford University Press). | |||

* Kleinig, J. (2010) 'The Nature of Consent', in: Miller, G. & Wertheimer, A. (eds.)(2010) The Ethics of Consent: Theory and Practice (Oxford: Oxford University Press). | |||

* Kramer Bussel, R. (2008) 'Beyond Yes or No: Consent as Sexual Process', in Freidman, J. & Valenti, J. (eds) Yes Means Yes: Visions of Female Sexual Power and a World Without Rape (California: Seal Press). | |||

* Miller, G. & Wertheimer, A. (eds.)(2010) The Ethics of Consent: Theory and Practice (Oxford: Oxford University Press). | |||

* Millar, Thomas M. (2008) 'Towards a Performance Model of Sex', in Freidman, J. & Valenti, J. (eds) Yes Means Yes: Visions of Female Sexual Power and a World Without Rape (California: Seal Press). | |||

* Rape Crisis Scotland (2008) This Is Not an Invitiation to Rape Me [campaign]. Available at: www.thisisnotaninvitationtorapeme.co.uk (Accessed 1 December 2012). | |||

:: (2010) Not Ever [campaign]. Available at: http://www.notever.co.uk (Accessed 1 December 2012). | |||

:: (2011) Pie Chart Postcard [campaign]. Available at: www.rapecrisisscotland.org.uk/workspace/uploads/files/chart.pdf (Accessed 1 December 2012). | |||

* Reclaim The Night Oxford (2011) Reclaim The Night [online]. Available at: http://oxfordfeminist.ox4.org/rtn (Accessed 1 December 2012). | |||

* Schwyzer, H. (2008) The Opposite of Rape is Not Consent; the Opposite of Rape is Enthusiasm [online]. Available at: http://www.hugoschwyzer.net/2008/06/15/the-opposite-of-rape-is-not-consent-the-opposite-of-rape-is-enthusiasm-a-revised-and-expanded-post/ (Accessed 1 December 2012). | |||

* Wertheimer, Alan (2003) Consent to Sexual Relations (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press). | |||

===Consensus=== | |||

* Epstein, M. (1996) 'Bare Attention', in: Thoughts Without A Thinker (New York: Basic Books). | |||

* Hardt, M. & Negri, A. (2004) Multitude: war and democracy in the Age of Empire (New York: Penguin). | |||

* Seeds for Change (2012a) Consensus Decision Making [online]. Available at: http://www.seedsforchange.org.uk/consensus (Accessed 1 December 2012). | |||

::(2012b) Facilitating Meetings: A Short Guide [online]. Available at: http://www.seedsforchange.org.uk/free/shortfacilitation#skills (Accessed 1 December 2012). | |||

Latest revision as of 22:21, 3 December 2012

General Introduction

"If I am struggling for autonomy, do I not need to be struggling for something else as well, a conception of myself as invariably in community, impressed upon by others[?]"

(Butler 2004, p.21).

I will be creating a collaborative online publishing tool. It will invite participants to produce a publication about consent, in a way which encourages self-awareness about the dilemmas and compromises of working together consensually. The project will use networked publishing and web-to-print tools in order to do this. It will be situated within current feminist debates surrounding consent, as a microcosm of wider discussions of how we are to live democratically together.

Social Context: The Feminist "Consent" Debate

"The issue of 'consent'... is about more than the letter of the law, and, like all sexual issues, at its heart is communication."

(Kramer Bussel 2008, p.43)

The questions of how people negotiate consensually, and what it means to do this, have long been a fascination in my work and activism. It is widely held that governments derive legitimacy from "the consent of the governed" (Johnston 2010), and many leftwing groups take this idea to its logical conclusion in their use of Consensus decision-making. Consensus means "looking for 'win-win' solutions [in which] everyone agrees with the final decision" (Seeds for Change, 2012a). However, a closer look at what it means to "consent" poses challenges to this ideal. Under what conditions do we consent, and is consenting the same as really endorsing something? Can and should we consent out of solidarity to something we do not want? One field which is actively posing these questions is the feminist anti-rape movement, in which I have been active for several years and for which "consent" is of central concern. This field has interesting contributions to make to broader debates about how we are to live democratically together.

The anti-rape movement makes frequent reference to "consent" as the vital missing ingredient in abusive encounters. (As legal theorists put it, consent works a "moral magic", which makes otherwise impermissable acts permissable (Kleinig, 2010)). It thus campiagns tirelessly under the banner "No Means No", stressing that explicit consent - "saying yes" (Reclaim the Night Oxford, 2011)- should be sought, communicated and respected. (For further examples of this approach see Rape Crisis Scotland 2008, 2010 & 2011.)

This discourse paints a black and white picture: either consent is given, or it is not, and only the most explicit of gestures ("saying yes") counts as valid consent. Ensuring that sexual subjects, as one government campaign put it, "get a 'yes' before sex" (Home Office, 2006) appears at first glance to be the highest goal of this movement. Its demands map closely onto dominant legal conceptions of consent as something which is sought by an active party, and either given or withheld by a reactive other (Kleinig, 2010).

However, there is a growing call from within the feminist movement to expand the definition of valid consent from simply "saying yes", to a broader one including the process of negotiation itself. This trend is summed up in the title of Schwyzer's (2008) article, "The Opposite of Rape is not Consent: The Opposite of Rape is Enthusiasm". Schwyzer debunks the claim that "yes means yes", noting the vital distinction between giving consent and actually wanting something. Other feminist writers attempt to bridge this distinction by re-defining consent entirely. Proposals for a new definition have included "an active collaboration for the benefit... of all persons concerned" (Easton & Liszt, 1997), "an open dialogue" (Kramer Bussel, 2008), and a "process" based on "affirmative participation" (Millar, 2008).

This debate about how exactly we should define consent is still emerging, and can be brought into fruitful dialogue with the question of how we might use networked media to collaborate in a democratic manner. These feminist models make vital distinctions between wanting something, endorsing something, and cooperating with something. Applied to democratic processes, they make clear that people who vote for something (even in a Consensus system) may not actually want it. This raises difficult and relevant questions for networked collaboration, asking how and why we cooperate with others.

By chosing this social context I aim to work with people who are already familiar with debates surrounding "consent", in order to facilitate a process of teasing out some of the dilemmas and contradictions that it throws up. I will treat this specific context as a microcosm, with potentially useful contributions to wider debates about how we are to co-exist consensually (ie, democratically) as people. The field of feminist activism is an ideal setting in which to make these links between interpersonal consent and democratic consent more generally, as an activist movement by definition is faced not only with questions of "consent" as discussed above, but with the practical question of how to agree and act together as a movement of many individuals and groups. So, the primary audience and participants in the project will be those active in this feminist community. The secondary audience will be those interested in how the project's processes and outcomes contribute to discussions about consensual relations more broadly.

Relation to previous work

This project continues a practice which self-reflexively analyses the way that groups organize. I take as subject, audience and participants those whose intention is to critique the non-consensual or undemocratic organization of society as it stands, and investigate how these groups organize in practice. In 2010 I set up the online platform Radical X to this end, which facilitates dialogue-based projects within activist communities: precisely those groups wrestling with what it means to consent, how far solidarity should extend, and how we might work together to articulate a shared vision. It has invited both bridge-building between apparently hostile communities (in the conversation and publishing project Play!Fight!, 2010), and highlighting of disagreements between those who seem to share common ground (in the collaborative writing project Open Sauce, 2011). Both these projects used debates about sexual politics as a "way in" to broader questions about how we negotiate the compromises inherent in interpersonal relations and democracy. It was important to both projects that the subject matter was embedded in the process of the projects themselves: a project about a clash of cultures set up and analysed this clash (by, for example, inviting speakers from one community into a physical space organized by another); a project about how fantasies are formed created a tool through which this process could happen and be analyzed (by using an open-access wiki for collaborative writing).

Given the importance of investigating the subject of democratic negotiation through democratic processes, it became problematic that my role as facilitator involved a strong element of hierarchical curation (for example, chosing which texts to include in the end publication of Play!Fight!).

'Open Sauce' (2011, Fig.2) began experimenting with handing over curation to the project's participants. In fact, observing the way in which participants edited each others' work became the most interesting aspect of the project. A developing fascination here was in the power of the editor/curator either to promote or to erase the words of others. I was fascinated by observing how this power is exercised.

My interest in the conflicting desires to echo and to erase others' views was continued in 'The Dissolute Image' (2012, Fig.3), which confronted participants more directly with the question of whether they would enable the distribution of other people's (possibly objectionable) content. An image which had been censored from Facebook was divided into its individual pixels, with each one offered up for 'adoption' on participants' own websites. Only when all 95,000 pixels have been 'adopted' (posted on participants' own sites) will the image fully reappear. The vulnerability of digital files to their need for physical storage was also highlighted in the related project 'Volunteer Hosts' (2012, Fig.4), in which volunteers agreed to store a digital file about their person without knowing in advance what it contained.

This project will bring the above explorations of what it might mean to 'facilitate' or 'transmit' back to the Radical X platform and its concern with sexual politics. Just as the question for feminists is, "is consenting to somthing the same as wanting it?", the question explored in the above projects is, "is hosting or transmitting something the same as endorsing it?". The project will develop processes for collaborative production which look critically at the role of those who transmit, publish or filter the works of others. The theme of "consent" will bring focus to this process, exploring (and embodying) questions such as: what does it mean to agree? What does it mean to endorse? And how far should cooperation with our allies extend?

In order to do this, the project will look for technical models which enable the decentralization of curation/publishing of documents, so that participants can be confronted directly with these questions (rather than having them resolved through centralized curation).

Technical Tools and Context

'The Dissolute Image' and 'Volunteer Hosts' both stressed the reliance of digital documents on those who host or transmit them. This research responds to the wider context in which online publishing has radically changed what it means to publish a cultural object, and what the nature of that object is. No longer singular and stable, networked documents are vulnerable to others with which they are linked. (For example: dynamic websites break when an API is changed; images embedded from other servers can disappear; RSS feeds fill sites with unpredictable external content.) This has brought with it an exciting uncertainty about the status of the singular, autonomous agent (author) who creates and controls a discrete document. I have argued elsewhere that this brings tremendous opportunity for less defensive forms of sociality, while also posing frightening threats to our belief in an autonomous individual self. There are rich links to be made here with the debates about negotiation and consent discussed above, which deal with how and why we cooperate with others. The field of digital publishing, then, is an ideal technical context and starting-point.

While the 'porous' nature of digital documents has tremendous social potential, the "atomization of content" (Ludovico, 2012) which it creates tends currently to serve quite different ends. As Ludovico, Parisier (2011) and IMC London (2012) point out, the devolution of curatorial power to individual users is currently more likely to create a personalized "filter bubble" than to expose readers to a broad range of challenging content. Those who helped to articulate this problem are turning back to paternalistic curation as a solution (Parisier & Peter Koechley's new anti-filter bubble service is "starting out with a heavy focus on curation — finding and sharing the best important stuff that the Internet generates each day" (Upworthy, 2012)). Others, such as outgoing Indymedia collective IMC London, express the vague and unmet need for "curation from within the sea of content" which "foster[s] true collaboration and solidarity" (IMC London 2012).

What kinds of digital publishing tools could enable such a process, which does not resort to centralized curation but encourages the kind of dialogue-based collaboration envisioned by the feminist writers discussed above?

Wikis

My first experiment with collaborative publishing ('Open Sauce') used a wiki, which enables multiple versions of a text to be saved on top of one another by many different writers. This worked for raising the question of whether to cooperate or compete (without centralized curation), as any participant could erase words in a previous version or keep them intact. However, the easy ability to delete disliked text didn't challenge participants as much as it might have done with the responsibility of leaving words intact which they disagreed with. Also, as the wiki was a single central site, participants weren't challenged with the question of whether they would publish the text themselves. The singular, chronological form of a wiki lends itself to the idea that a text is to be 'improved' - rather than a model of possibily overlapping, provisional collections of texts (as per the consent model) which are not striving chronologically towards a united idea of 'truth' or 'quality'.

Embedding

The use of image embedding (displaying an image on a webpage by linking to the file on another site) is another technology I've explored. In 'The Dissolute Image' and more recent prototypes using image embedding, participants are challenged more explicitly to display content from external sites which they don't control. This gets closer to my interests than the use of wikis, with their focus on altering the content provided by others. Embedding is limited, however, by its unsuitability for content other than image and video, and by the fact that links are only one-way: there is no way to keep track of who is participating.

Web scraping

Web scraping - the automated extraction of content from a website for use elsewhere - is in some ways more sophisticated than embedding. I used it for a recent prototype which questions what it means to endorse a slogan, by generating placards automatically from online socialist headlines (Fig. 5). Unlike embedding, scraping allows for text content to be found and manipulated. However, specific types of content have to be searched for by a piece of software, taking away the simplicity found in simply embedding an image file, and thus making it harder to participate. It is also unclear how a project using web scraping would be able to coordinate or keep track of participants. It could be used to raise interesting questions about consent, however, as it is usually employed to extract information without permission from a site owner.

Peer to Peer filesharing

Having explored the technologies above, my next step will be to better understand peer to peer models of circulating content. I will be looking for what these models have to offer in terms of circulation of files without centralized control, and the use of indexes or trackers to coordinate a horizontal group of participants.

Collaborative Authoring Tools & Web-to-Print

Software which converts online files to print-ready documents has exciting potential to produce a physical outcome from a deliberative, online process of writing. I will be researching tools such as Booki, looking at how their conversion of online to paper content could be applied to a tool which encourages the type of social encounters described above. GIT

By better understanding these models, I aim to revisit the technologies above and incorporate them into a publishing tool which:

- Enables the contribution of content by participants

- Enables the publishing or circulation of that content by other participants

- Challenges participants to re-circulate content they may disagree with

- Blurs the clear lines between different authors and their opinions

- Allows participants to create physical documents (for example, magazines or flyers) from this online content.

Next Steps

This project has two practical aspects: a social one, and a technological one.

The social aspect of the project will involve making links with people and groups in the community described above. This means meeting with people immersed in debates about consent, and finding out in more detail what dilemmas and questions arise for them from this field of activism. It will also involve finding out where points of intervention in this field might be (whether this is particular publications, events, or discussions) and what forms that intervention should take in order to respond in a relevant, comprehensible way.

The technological aspect will be developed alongside this, looking for technologies which fulfil the requirements emerging from the social context. It will involve better understanding the technologies mentioned above (peer to peer models, collaborative authoring and web-to-print tools), and experimenting with how these can be used and/or re-purposed to create a custom puslishing tool. After developing initial prototypes I hope to participate in the 'Post-Digital' print lab proposed by Florian Cramer at Transmediale 2013, in order to experiment in a hands-on way with how these technologies could be used to produce physical documents through a deliberate social process.

Bibliography

Publishing

- Ludovico, Alessandro (2012) Post Digital Print: The Mutation of Publishing since 1894 (Eindhoven: Onopatopee).

- Garsiel, Tali (2011) How Browsers Work: Behind the Scenes of Modern Web Browsers [online]. Accessed 19 October 2012 at http://taligarsiel.com/Projects/howbrowserswork1.htm.

- IMC London (2012) Time to move on: IMC London signing off [online]. Accessed 13 October 2012 at http://london.indymedia.org/articles/13128

- Pariser, E. (2011) The Filter Bubble: How the New Personalized Web Is Changing What We Read and How We Think (London: Penguin).

- Upworthy (2012) Could This Be The Most Upworthy Site In The History Of The Internet? [online]. Available at: http://www.upworthy.com/could-this-be-the-most-upworthy-site-in-the-history-of-the-internet (Accessed 1 December 2012).

Consent

- Butler, J. (2004) 'Beside Oneself: On the Limits of Sexual Autonomy' in Undoing Gender (London: Routledge).

- Easton, D. & Liszt, C. A. (1997) The Ethical Slut: A Guide to Infinite Sexual Possibilities (Oregon: Greenery Press).

- Home Office (2006) If You Don't Get a 'Yes' Before Sex, Who'll Be Your Next Sleeping Partner? [campaign] PDF available at: http://www.homeoffice.gov.uk/documents/consent-campaign/Prison.pdf?view=... (Accessed 1 December 2012).

- Johnston, J. (2010) 'A History of Consent in Western Thought', in: Miller, G. & Wertheimer, A. (eds.)(2010) The Ethics of Consent: Theory and Practice (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

- Kleinig, J. (2010) 'The Nature of Consent', in: Miller, G. & Wertheimer, A. (eds.)(2010) The Ethics of Consent: Theory and Practice (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

- Kramer Bussel, R. (2008) 'Beyond Yes or No: Consent as Sexual Process', in Freidman, J. & Valenti, J. (eds) Yes Means Yes: Visions of Female Sexual Power and a World Without Rape (California: Seal Press).

- Miller, G. & Wertheimer, A. (eds.)(2010) The Ethics of Consent: Theory and Practice (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

- Millar, Thomas M. (2008) 'Towards a Performance Model of Sex', in Freidman, J. & Valenti, J. (eds) Yes Means Yes: Visions of Female Sexual Power and a World Without Rape (California: Seal Press).

- Rape Crisis Scotland (2008) This Is Not an Invitiation to Rape Me [campaign]. Available at: www.thisisnotaninvitationtorapeme.co.uk (Accessed 1 December 2012).

- (2010) Not Ever [campaign]. Available at: http://www.notever.co.uk (Accessed 1 December 2012).

- (2011) Pie Chart Postcard [campaign]. Available at: www.rapecrisisscotland.org.uk/workspace/uploads/files/chart.pdf (Accessed 1 December 2012).

- Reclaim The Night Oxford (2011) Reclaim The Night [online]. Available at: http://oxfordfeminist.ox4.org/rtn (Accessed 1 December 2012).

- Schwyzer, H. (2008) The Opposite of Rape is Not Consent; the Opposite of Rape is Enthusiasm [online]. Available at: http://www.hugoschwyzer.net/2008/06/15/the-opposite-of-rape-is-not-consent-the-opposite-of-rape-is-enthusiasm-a-revised-and-expanded-post/ (Accessed 1 December 2012).

- Wertheimer, Alan (2003) Consent to Sexual Relations (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Consensus

- Epstein, M. (1996) 'Bare Attention', in: Thoughts Without A Thinker (New York: Basic Books).

- Hardt, M. & Negri, A. (2004) Multitude: war and democracy in the Age of Empire (New York: Penguin).

- Seeds for Change (2012a) Consensus Decision Making [online]. Available at: http://www.seedsforchange.org.uk/consensus (Accessed 1 December 2012).

- (2012b) Facilitating Meetings: A Short Guide [online]. Available at: http://www.seedsforchange.org.uk/free/shortfacilitation#skills (Accessed 1 December 2012).