User:Dusan Barok/Monoskop library (project proposal): Difference between revisions

| (One intermediate revision by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 10: | Line 10: | ||

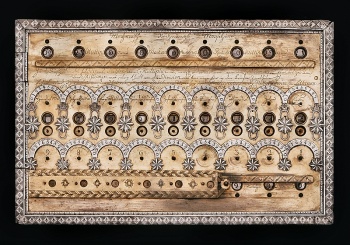

[[File:1970, ansamblu mobi (sigma) 1222244234.jpg|thumb|350px|Sigma group, ''Ansamblu Mobil'', 1970. Suspended aluminium plates, 350x120x30 cm.]] | [[File:1970, ansamblu mobi (sigma) 1222244234.jpg|thumb|350px|Sigma group, ''Ansamblu Mobil'', 1970. Suspended aluminium plates, 350x120x30 cm.]] | ||

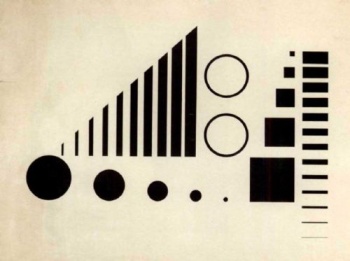

[[File:Vasulka, Steina and Woody (1974) - Noisefields.jpg|thumb|350px|Steina and Woody Vasulka, ''Noisefields'', 1974. Video still.]] | [[File:Vasulka, Steina and Woody (1974) - Noisefields.jpg|thumb|350px|Steina and Woody Vasulka, ''Noisefields'', 1974. Video still.]] | ||

Over the years I have collected | Over the years I have collected approximately 100 gigabytes of experimental films, video art, electroacoustic music, scanned versions of computer-aided paintings, graphics, prints, and numerous publications covering the development of media arts and media culture. I have focused primarily on those works which I found to be relevant, but not appropriately represented in the canon of art history. Obviously, this collection is only the tip of the iceberg, as there are many more such treasures in the private archives of other collectors. After being asked so many times to share a film or a recording, I decided to share them all. How come? | ||

Almost a decade ago I was | Almost a decade ago, I was a member of a [http://monoskop.org/Burundi media lab] in Bratislava, Slovakia. We organised free software workshops, evenings of media theory, a new-media culture festival, street projects, hardware recycling, and so on. The niche culture we belonged to was generally regarded as ‘new media’. Our main struggle was with the limited size of the audience we could reach. Recurring questions included: is ‘new media’ really so new, if computers have been around since the Second World War? Why does mankind need noise music? What makes signal processing into ‘art’? Interdisciplinarity and the international networks which we were a part of, were not enough to legitimise our work. It was mainly this frustration which led me to dig deeper into the past, and to trace the origins of ‘new media’ culture, all the way back to before it was ‘new’. In order to document this process I set up a Wiki website, [http://monoskop.org Monoskop], which gradually came to be known as an independent resource for research in media arts and culture. | ||

In principle, content | In principle, all content on the website is created openly and collaboratively. Anyone is welcome to edit and add new information – similarly to Wikipedia, except that Monoskop is primarily focused on media culture. In the past eight years it has expanded, both in size and in level of detail, and is now structured into various themes and sub-categories. Monoskop pages now cover a wide variety of subjects: biographies, records of events, academic programmes, cultural servers, mailing lists, etc. Monoskop focuses on digital cultures which have emerged from local and international grassroots networks (FLOSS, tactical media, open spectrum) but also from academies (digital humanities, software studies) and even corporations (social media), as well as those that were ‘born digital’ (surf clubs). Monoskop is unique in its particular focus on local scenes, mapped in [http://monoskop.org/Template:Cities city entries] spanning the last two decades or so. Other pages, catalogued by [http://monoskop.org/Template:Countries country of origin], explore in more detail the history – following the trails and pinpointing the intersections of art and technology since the 1910s. | ||

As I was compiling bibliographies, I realised I could only find literature covering relatively small sections of this field. This led me, in collaboration with Tomáš Kovács, to launch a side project inspired by music blog culture: [http://monoskop.org/log/ Monoskop/log], a place where one can find electronic versions of books, journals, catalogues and essays related to media culture. It took me some time to realise that, of the nearly 2,000 publications on the blog, only a small fraction dealt specifically with media culture in central and eastern Europe. I also noticed that the media departments in academies and universities tend to focus on a mix of American and local national discourse, and thus lack a perspective focused on the region as a whole. So I created on the Wiki a new page (which may also be considered as an entity in its own right), a kind of entry gate focusing on [http://monoskop.org/Media_art_in_CEE central and eastern Europe]. | |||

However, | However, one thing missing here is the artworks themselves. This is mainly due to the original decision not to get involved too deeply in copyright issues for the Wiki. So all the gifts, CDs, DVDs, all the files scraped from websites, private torrents, and closed academic archives, which I had collected in the course of my research, ended up being locked on my hard drives. But the experience, and the positive feedback Monoskop/log has received from students, teachers, and even authors who found their works online, finally convinced me that it does make sense to share it. Which brings me back to the collection I mentioned at the beginning. How to make it public? | ||

==Current structure== | ==Current structure== | ||

| Line 208: | Line 208: | ||

In December I participated at a [http://najave.razmjenavjestina.org/2011/12/01/g33koskop-seminar-03-12-2011-1500-o-arhivi-i-knjiznici/ seminar at Mama club] in Zagreb, Croatia, to discuss the idea of a library for the first time in public. I gave a wider [http://burundi.sk/monoskop/index.php/Monoskop/Zagreb_2011_talk introduction to the project] and the following discussions helped me to articulate what is crucial. | In December I participated at a [http://najave.razmjenavjestina.org/2011/12/01/g33koskop-seminar-03-12-2011-1500-o-arhivi-i-knjiznici/ seminar at Mama club] in Zagreb, Croatia, to discuss the idea of a library for the first time in public. I gave a wider [http://burundi.sk/monoskop/index.php/Monoskop/Zagreb_2011_talk introduction to the project] and the following discussions helped me to articulate what is crucial. | ||

Three | Three essential goals for the collection became clear: reaching the widest possible audience (including researchers); involving more people in sharing their rare content; and maintaining public access. Rather than attempting to create some grand historical narrative interweaving the content, the goal is instead to provide quotable online resources and to unlock these resources, thus enabling other researchers to produce alternative art histories. Although there are thousands of different databases and archives with advanced search options, people looking for content (including researchers) tend to simply search Google’s database. Therefore, for the collection to reach people, it must be indexed by search bots. | ||

==Work plan== | ==Work plan== | ||

Latest revision as of 20:28, 14 June 2012

- Public library of media arts and culture

Outline

Over the years I have collected approximately 100 gigabytes of experimental films, video art, electroacoustic music, scanned versions of computer-aided paintings, graphics, prints, and numerous publications covering the development of media arts and media culture. I have focused primarily on those works which I found to be relevant, but not appropriately represented in the canon of art history. Obviously, this collection is only the tip of the iceberg, as there are many more such treasures in the private archives of other collectors. After being asked so many times to share a film or a recording, I decided to share them all. How come?

Almost a decade ago, I was a member of a media lab in Bratislava, Slovakia. We organised free software workshops, evenings of media theory, a new-media culture festival, street projects, hardware recycling, and so on. The niche culture we belonged to was generally regarded as ‘new media’. Our main struggle was with the limited size of the audience we could reach. Recurring questions included: is ‘new media’ really so new, if computers have been around since the Second World War? Why does mankind need noise music? What makes signal processing into ‘art’? Interdisciplinarity and the international networks which we were a part of, were not enough to legitimise our work. It was mainly this frustration which led me to dig deeper into the past, and to trace the origins of ‘new media’ culture, all the way back to before it was ‘new’. In order to document this process I set up a Wiki website, Monoskop, which gradually came to be known as an independent resource for research in media arts and culture.

In principle, all content on the website is created openly and collaboratively. Anyone is welcome to edit and add new information – similarly to Wikipedia, except that Monoskop is primarily focused on media culture. In the past eight years it has expanded, both in size and in level of detail, and is now structured into various themes and sub-categories. Monoskop pages now cover a wide variety of subjects: biographies, records of events, academic programmes, cultural servers, mailing lists, etc. Monoskop focuses on digital cultures which have emerged from local and international grassroots networks (FLOSS, tactical media, open spectrum) but also from academies (digital humanities, software studies) and even corporations (social media), as well as those that were ‘born digital’ (surf clubs). Monoskop is unique in its particular focus on local scenes, mapped in city entries spanning the last two decades or so. Other pages, catalogued by country of origin, explore in more detail the history – following the trails and pinpointing the intersections of art and technology since the 1910s.

As I was compiling bibliographies, I realised I could only find literature covering relatively small sections of this field. This led me, in collaboration with Tomáš Kovács, to launch a side project inspired by music blog culture: Monoskop/log, a place where one can find electronic versions of books, journals, catalogues and essays related to media culture. It took me some time to realise that, of the nearly 2,000 publications on the blog, only a small fraction dealt specifically with media culture in central and eastern Europe. I also noticed that the media departments in academies and universities tend to focus on a mix of American and local national discourse, and thus lack a perspective focused on the region as a whole. So I created on the Wiki a new page (which may also be considered as an entity in its own right), a kind of entry gate focusing on central and eastern Europe.

However, one thing missing here is the artworks themselves. This is mainly due to the original decision not to get involved too deeply in copyright issues for the Wiki. So all the gifts, CDs, DVDs, all the files scraped from websites, private torrents, and closed academic archives, which I had collected in the course of my research, ended up being locked on my hard drives. But the experience, and the positive feedback Monoskop/log has received from students, teachers, and even authors who found their works online, finally convinced me that it does make sense to share it. Which brings me back to the collection I mentioned at the beginning. How to make it public?

Current structure

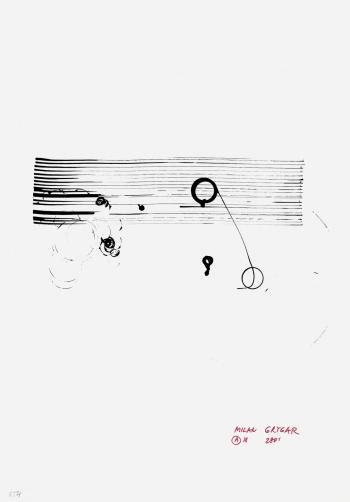

Monoskop - Source Documents for Media Arts and Culture/ ├── 01 CONSTRUCTIVISM │ ├── Alge │ ├── Bauhaus │ ├── Berlewi, Henryk │ ├── Contimporanul │ ├── De Stijl │ ├── Fulla, Ľudovít │ ├── Gabo, Naum │ ├── Kallai, Erno │ ├── Kassák, Lajos │ ├── Klutsis, Gustav │ ├── Lissitzky, El │ ├── Malevich, Kazimir │ ├── Micić, Ljubomir │ ├── Modern Architecture │ ├── Moholy-Nagy, László │ ├── Molnár, Farkas │ ├── Productivists │ ├── Punct │ ├── Rodchenko, Alexander │ ├── Strzemiński, Wladyslaw │ ├── Tatlin, Vladimir │ ├── VKhUTEMAS │ ├── Zenit │ └── Literature ├── 02 LITERATURE, LITERARY THEORY, AESTHETICS │ └── Literature ├── 03 AUDIOVISUAL COMPOSITIONS │ ├── Grygar, Milan │ └── Literature ├── 04 EXPERIMENTAL FILM │ ├── Acimovic-Godina, Karpo │ ├── Antonisz, Julian Józef │ ├── Bódy, Gábor │ ├── Borowczyk, Walerian │ ├── Burian, E.F.; Zahradníček, Čeněk │ ├── Dodal, Karel; Dodalová, Irena │ ├── Ďurček, Ľubomír │ ├── Forgacs, Peter │ ├── Frič, Martin │ ├── Gotoslav, Tomislav │ ├── Hammid, Alexander │ ├── Havrilla, Vladimir │ ├── Kinema Ikon │ ├── Kinoautomat │ ├── Kováč, Ctibor │ ├── Kristl, Vlado │ ├── Królikiewicz, Grzegorz │ ├── Kučera, Jan │ ├── Kucia, Jerzy │ ├── Lehovec, Jiří │ ├── Lenica, Jan │ ├── Makavejev, Dušan │ ├── Matić, Ivica │ ├── Moholy-Nagy, László │ ├── Narkevicius, Deimantas │ ├── Neumann, Hieronim │ ├── Petek, Vladimir │ ├── Rybczynski, Zbigniew │ ├── Skolimowski, Jerzy │ ├── Slivka, Martin │ ├── Themerson, Stefan and Franciszka │ ├── VA - Anthology of Polish Experimental Animation (1944 - 2007) DVD │ ├── VA - Hungarian short films - Vol. 1 │ ├── VA - Hungarian short films - Vol. 2 │ ├── VA - Serbian Alternative Film 1950-1990 │ ├── Vávra, Otakar │ ├── Vertov, Dziga │ ├── Warsztat Formy Filmowej │ └── Literature ├── 05 CYBERNETICS, TECHNOLOGY AND POLITICS │ ├── Jakobson, Jewna │ └── Literature ├── 06 ELECTROACOUSTIC MUSIC │ ├── Bánkövi, Gyula │ ├── Chojnacka, Elisabeth │ ├── Detoni, Dubravko │ ├── Dobrowolski, Andrzej │ ├── Dumitrescu; Avram; Hodgkinson; Cutler │ ├── Hyperion Ensemble │ ├── Jovanovic, Arsenije │ ├── Knížák, Milan │ ├── Koenig; Pongrácz; Riehn │ ├── Kotonski, Wlodzimierz │ ├── Krček, Jaroslav │ ├── Lazarov, Simo │ ├── Ligeti, György │ ├── Malec, Ivo │ ├── Marbe, Myriam │ ├── Mazurek, Bohdan │ ├── Nemescu, Octavian │ ├── Penderecki, Krzysztof │ ├── Piňos; Blatný; Ištvan; Štědroň │ ├── Pongrácz, Zoltán │ ├── Rääts, Jaan │ ├── Rudnik, Eugeniusz │ ├── Slovakia │ ├── Szigeti, István │ ├── VA - Elektroakusticka hudba │ ├── VA - Radioacustica Selected 2003 │ ├── VA - Radioacustica Selected 2009 │ └── Literature ├── 07 PERFORMANCE │ └── Literature ├── 08 MULTIMEDIA ENVIRONMENTS │ └── Literature ├── 09 VISUAL RESEARCH, KINETIC ART, OP ART │ └── Literature ├── 10 DYNAMIC OBJECTS, CYBERNETIC SCULPTURE │ └── Literature ├── 11 COMPUTER ART │ ├── Byte │ ├── Dróżdż, Stanisław │ ├── Epure, Sherban │ ├── Flondor, Constantin │ ├── PAGE │ ├── Sayler, Diet │ ├── Sýkora, Zdeněk │ └── Literature ├── 12 VIDEO │ ├── Art in Windows (2000) CD │ ├── Barla Videojournal CD │ ├── From Monument To Market (Od Monumentu do Marketu, 2005) DVD │ ├── inyfilm.sk │ ├── Mediálne umenie na Slovensku (2006) DVD │ ├── Petr Skala - A Hidden Experimenter (1969-1993) DVD │ ├── Robakowski, Józef │ ├── Ronai, Peter │ ├── Transitland collection │ ├── Vasulkas │ ├── Vipotnik, Miha │ └── Literature ├── 13 ELECTRONIC MUSIC │ ├── Abbildungen Variete │ ├── Aporea │ ├── Mario Marzidovsek │ ├── Naj │ ├── NSRD et al │ ├── P.P. Nikt │ └── Literature ├── 14 NEW MEDIA ART, MEDIA CULTURE │ ├── Hlinka, Zden │ ├── Szegedy-Maszák, Zoltán │ ├── Yugoslav and Serbian Demoscene (1994-2001) │ └── Literature └── 15 ART THEORY, ART HISTORY, MEDIA THEORY ├── Arkzin ├── Arns, Inke ├── Cseres, Jozef ├── Czegledy, Nina ├── Dan, Cãlin ├── Denegri, Jerko ├── Fabuš, Palo ├── flusserstudies-CS-issue ├── Flusser, Vilém ├── Frakcija ├── Further literature ├── Groys, Boris ├── Gržinić, Marina ├── IDEA ├── Interviu ├── Kelomees, Raivo ├── Kluszczynski, Ryszard ├── kuda.org ├── Long April ├── Meštrović, Matko ├── Murin, Michal ├── Peternák, Miklós ├── Piotrowski, Piotr ├── Pospiszyl, Tomas ├── Praktyka Teoretyczna ├── Prelom ├── Red Thread ├── Rišková, Mária ├── Scholz, Trebor ├── Sei, Keiko ├── TkH ├── van Belle, Guy ├── Vojtechovský, Miloš └── Further literature

Objectives

In December I participated at a seminar at Mama club in Zagreb, Croatia, to discuss the idea of a library for the first time in public. I gave a wider introduction to the project and the following discussions helped me to articulate what is crucial.

Three essential goals for the collection became clear: reaching the widest possible audience (including researchers); involving more people in sharing their rare content; and maintaining public access. Rather than attempting to create some grand historical narrative interweaving the content, the goal is instead to provide quotable online resources and to unlock these resources, thus enabling other researchers to produce alternative art histories. Although there are thousands of different databases and archives with advanced search options, people looking for content (including researchers) tend to simply search Google’s database. Therefore, for the collection to reach people, it must be indexed by search bots.

Work plan

- Let the archive be indexed by crawlers by publishing it on a wiki

Rethink the folder structure. Upload archive to a server, possibly in several rounds. Install Semantic Mediawiki extension to the Monoskop wiki, which already includes hundreds of artist biographies and contextual information. Create semantic templates for artists, works, and fields there. Make semantic wiki pages for particular works from the archive, linking them to the media file on the server; make use of the Mediawiki Widgets. Consider distributed video streaming. Embed published works within artist pages: this will create Wikipedia-style artist profiles which also include preview of artworks -- impossible on Wikipedia due to copyright limitations. Publish the updates across social media, aim for the widest reach, ask for new contributions.

- Distribute the archive across the peer network via dumps and torrents

Make wiki content dumps, one package for all text, all images, all video files, and all sound files. Create torrent backups for each package using BurnBit torrent backup system, which is also used by Wikipedia. Alternatively, contact ArchiveTeam.org and Archive.org for mirrors. Announce packages and torrents across social media.

- Situate the works within various online contexts as curated selections

Propose the selections to curated online archives such as Ubu, and create the readers and media anthologies on popular filesharing platforms, Aaaarg.org, Karagarga torrent tracker, and so on. These can be done in collaboration with invited artists and cultural practitioners, building upon their works, syllabi, or other research.

- Data analysis

Make use of semantic annotation, create special pages using inline queries. Analyse collected works using computational methods from digital humanities and software studies. Publish the scripts.

Recent works

Faceleaks

Faceleaks is a Firefox/Chrome add-on which attaches a leak button to Facebook photos, allowing user to leak them to www.faceleaks.info website which has a visual appearance of Wikileaks Cablegate website.

The browser add-on is a Greasemonkey user script written in JavaScript language and subsequently compiled to XPI format compatible with Firefox browsers. The add-on was then pointed to forward the leaked Facebook pictures to the newly registered Faceleaks.info domain, which was designed to mock the Cablegate page at the Wikileaks.org website, including a logo of Facebook default icon mashupped with the official Wikileaks logo. The XPI file was uploaded to the official Add-ons for Firefox website maintained by Mozilla Foundation, along with the short description of the add-on. The information about the project was then sent to the experimental browser software repository, Artzilla.org, which included it in their database. Information about the project was shared via social networks without a direct interference of the author, also following the public presentation of the add-on at the Rebelhuis exhibition in Rotterdam. There was another version of add-on created in PEM format, compiled into CRX format for Chrome browsers, and included in the Faceleaks.info website. The source code for both versions was finally made publicly available and uploaded to Gitorious repository.

In November and December 2010 I was reading a lot about WikiLeaks and observing how the Cablegate story interacts within the media sphere. I perceived it as a convergence of crucial issues at stake for the contemporary politics and as many others I was discussing the potential it creates for political change. There were several threads, a question--of leaking as a creative act, of what is to be and what not to be linked to the public domain, of accountability and reponsibility, of information transparency, and of censorship. I was not able to answer the question of what gives the WikiLeaks organisation mandate to decide what sort of classified information made public is more likely to meet their maxim--to create more "just" world.

I was primarily interested in exploring a technique of leaking and apply a method of modifying technology shaping the society on a grand scale to see what would happen if control over leaking is given to a wide range of people. When talking to Michael, the moment we got an idea of embedding a leak button within the Facebook page, I realized how such a simple hack would go deep into the very idea social networks build upon: trust. WikiLeaks use similar hack to break a conspiracy in a corrupted governing body, giving its participants an anonymous 'leak' option. Facebook platform is entrusted by millions to keep their personal information "classified" to people they trust, and yet many downplay privacy concerns, and play. Faceleaks explores possibility of breaking a trust in favor of entertainment.

Social stock market

Social stock market was an idea of software which allows users to trade their friendships acquired at social media websites.

My ground assumption was that a social network profile is a commodity being produced by an user, a product of his or her labour of socialising online, while the sole extractor of its financial value being a network provider selling profiles to advertisers. The users--profile producers--are rewarded by the satisfaction from the ever rising number of friends displayed prominently at their profile pages as a kind of social relevance ratio, as the points the player collected in the social game. I wanted to explore the functioning of economic value system inherent in the social graph, make it more transparent and take it a step further.

The main question was 'how'. I imagined a software, a platform which would mirror social graphs of various networks (Facebook, Twitter, Myspace) and increase the value of a user each time he or she makes a new friendship, kind of an individual's social market value. The user would be thought as both a company issuing shares (requesting friendships) and a shareholder (having friendships with other users, in other words, owning shares at other companies). This would create an interesting situation, in which the value of all players raise in the most cases, since a friendship in the social network does not seem to be a scarce commodity. In theory, there were thousands of friends available for free, each a few clicks away, since both sides would always benefit from befriending each other. In other words, I was unable to create a more nuanced market situation, for instance to solve the issue of offer and demand, and how to make the friendship the desired object of consumption. Having more time for it, I would dive into issues of immaterial economy.

Rig

Rig was placed in an art gallery hosted by the local city hall as a computer which tries to generate money by running Bitcoin currency mining software. It consisted of a PC tower with a cover removed and a screen displaying the process, accompanied by printouts of cypherpunk and crypto-anarchist manifestos.

Bitcoin is a peer-to-peer currency. Peer-to-peer means that no central authority issues new money or tracks transactions. These tasks are managed collectively by the network. The participants store the money (bitcoins) on their computers and run the software to make transactions to others. To generate money the users are optionally running another piece of software, Bitcoin mining client on their machines, called the "mining rigs". The processing power of the rig mining network thus replaces the central authority issuing money. The exhibited computer was simply running a mining software processing and verifying the transactions in the bitcoin network, and during three weeks of the exhibition it mined about 1 cent.

I was primarily interested in exploring a potential the Bitcoin technology has as an alternative economy.

Bibliography

- The archive

- Florian Cramer, "Peer-to-Peer Services: Transgressing the archive (and its maladies?)", [1]

- Jacques Derrida, Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression. University of Chicago Press, 1996. [2] [3]

- Hal Foster, "An Archival Impulse", October, 2004. [4]

- Charles Merewether (ed.), The Archive. London: Whitechapel, 2006. [5]

- Archiving media art

- Annet Dekker (ed.), Archive2020 – Sustainable Archiving of Born-Digital Cultural Content. Virtueel Platform, 2010. [6]

- Joke Brouwer and Arjen Mulder (eds.), Making Art of Databases, Rotterdam: V2, 2003. [7]

- Nina Wenhart, "W0rdM4g1x. Or how to put a spell on Media Art Archives", January 2011, [8]

- Alain Depocas, Jon Ippolito, Caitlin Jones (eds.), Permanence Through Change: The Variable media Approach, New York: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, with Montreal: Daniel Langlois Foundation, 2003. English and French. [9]

- Sandra Fauconnier and Rens Frommé, Capturing Unstable Media: "Summary of Research Results", March 2003 [10]

- Filesharing

- Julian Myers, "Four Dialogues 2: On AAAARG", Aug 2009. [11]

- Janneke Adema, "Scanners, collectors and aggregators. On the ‘underground movement’ of (pirated) theory text sharing", Sep 2009. [12]

- Morgan Currie, "Small is Beautiful: a discussion with AAAARG architect Sean Dockray", Jan 2010. [13]

- "The AAAARG.org Discussion of the Macmillan Threat", Apr 2010. [14]

- Matthew Fuller, "In the Paradise of Too Many Books: An Interview with Sean Dockray", Mute magazine, May 2011. [15]