User:Rita Graca/gradproject/project proposal 6: Difference between revisions

Rita Graca (talk | contribs) |

Rita Graca (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 73: | Line 73: | ||

===Relation to a larger context=== | ===Relation to a larger context=== | ||

The urge to take control of our online spaces reveals the present concern over software pervasiveness, automation and accountability. Software is found on diverse objects and systems but is not always perceptible or understandable. In this way, software studies try to open the black box, looking for its methods and routines. (Kitchin and Dodge, 2011) However, opening the black box is not enough. Information without context, processing and analysing, is not accessible to the users. Furthermore, demanding transparency from big social media platforms doesn't provide the agency we seek as the ability to see doesn't mean the power to govern it. (Ananny and Crawford, 2016) At the same time, the increasing automation of our systems means even less control and less accountability. | |||

To overcome these difficulties, it makes sense to get around the software and focus on the relationship between the system and its users. Several projects work to visualise data, as a method for understanding relevant connections. Projects such as Ad.watch which compiles and visualises datasets of political ads on Facebook and Instagram to display the dubious relations between politics and social media platforms. Other projects decide to engage with the interface itself. Through plugins, add-ons, small robots and DIY techniques. Some authors encourage resistance arguing for alternative design practices through glitches, imperfect features, disturbing or illogical processes. (Hollanek, 2019) | |||

All these strategies support more user agency. As social media platforms become ubiquitous, spreading its convictions to billions of people, it is important to amplify these movements outside the tech world. It only makes sense to be part of a community that makes use of platforms in their own terms. | |||

<gallery widths = 400px heights=400px> | |||

File:adwatch.png| [https://ad.watch/ ad.watch] compiles and visualises datasets of political ads on Facebook and Instagram. This screenshot shows the activity of my city in Portugal. The political party that created controversial street billboards aimed at young people is also the biggest investor in social media advertising. | |||

</gallery> | |||

</div> | </div> | ||

===References=== | ===References=== | ||

Revision as of 11:25, 13 January 2020

Graduation Project Proposal

13 January 2020

What do you want to make?

In this project, I want to address my concerns with social interfaces. I propose to build a platform to publish a podcast and explore different methods of listening.

I want to give attention to the problematics of social platforms, by reaching out to people that have been engaging with actions of resistance. I aim to build a platform to share a series of conversations turned into a podcast. In each episode, I will invite a different person to discuss social networks, related to their practice or daily life. The podcast will be uploaded regularly to a platform where I can explore freely and prototype different ways of listening.

Listening doesn’t mean just hearing. The platform will allow paraphrasing, reinterpreting, annotating, and all different strategies I can explore for active listening. While I celebrate the actions of speaking up, I feel the need to provide the balance of receiving the information. I'm following closely Kate Crawford interest in assuming listening as a metaphor to capture forms of online participation. (Crawford, 2011) I hope this podcast, and the subsequent prototypes of listening, build a platform for understanding and reflection of our social networks.

My interest is focused on the design and architecture of social media platforms. The interface decides what the user can or cannot do, see and cannot see, deeply framing user behaviours. Social platforms present in the daily lives of most people are designed to reward attention. Attention comes from exaggerated actions, just like violence, harassment or SCREAMING. This benefits the social media business model, but not the well-being of the users. It also doesn't allow for bottom-up movements to thrive without following the same rules. Even online movements that fight to improve society, such as cancel culture, get entangled in the demands of mainstream social platforms. To stay relevant, they need to be viral. Aggressive. Almost scandalous.

Questions start to linger...

Is it possible to fight for a better society where the design is doomed to promote viral actions?

Do actions of protest change something or do they give an illusion of power?

How are social interfaces framing these movements?

How do you plan to make it?

I aim to create a digital audio file series. In each episode, I will be having a conversation with a guest actively involved in reshaping social media. I'm touching on topics of decentralisation, vigilantism, legislation. Alongside, I will explore strategies of care – I will prototype different features for the platform where the podcast is shared. These features are my experiences with different ways of listening. They can incorporate paraphrasing, reinterpreting, annotating, drawing, uploading, commenting, remixing, transcribing.

My platform serves a very specific purpose of giving me a boundless space for experiences. However, I intend to take the opportunity to share the project through different channels, looking into the mainstream and the alternatives. This can be a great moment to go through the design, accessibility and audience of such platforms. My experience with these projects will add up to my research on interface design. Different methods of distribution include peer-to-peer, such as Dat, or using mainstream options, such as Spotify or iTunes.

The tendency to build attractive, easy to use interfaces, can overlook and oversimplify some problems. Good design shouldn't mean a lack of disclosure or choice. These concerns noticeably apply to social media platforms. To pay attention to the actions of resistance is to acknowledge the need for change.

What is your timetable?

September, October — Ground my interests, make clear what I want to work on by researching and finding projects. Fast prototyping.

November, December — Project Proposal is written so my scope is set. Have a more specific direction for the prototypes. Who is my audience? Engage with users.

January — Allow the feedback from the assessment and the break to feed new inputs to the project. Organize a workshop (Py.rate.chnic sessions) which will allow other people to experiment and talk about the project.

February, March — Put my prototypes together to create a bigger platform. The project will expand from small experiments to a combined project. How will people engage with my project? Think about distribution, amplification and contribution from others!

April, May — Written thesis is delivered. Focus on the project. Test my prototypes, perform them or put them online. Is it useful to organise more workshops or conversations around the subject?

June, July — Finish everything: conclusion of the final project. Prepare the presentation.

Why do you want to make it?

Feels urgent. When diving into the subject of mainstream social media, the amount of noise is overwhelming. The lack of credibility of the media casts a shadow on genuine social movements and mobilisations online. There's urgency in amplifying authentic conversations. Conversations about the limitations of social interfaces, the changes we aim to see, possible solutions. There is so much noise on social media, it becomes urgent to listen.

Feels contemporary. The users have been demanding more reliable platforms and the companies picked out the trend by providing some changes. In April TikTok added two new features to promote a safer app experience. In July Instagram tested hiding its likes in several countries to benefit their users’ experience. Youtube promised to release soon new features in an attempt to be more transparent with their algorithms. It’s true that the real effects of these features are debatable and also part of well-thought marketing strategies. However, they show the audience is engaging with this type of discourses.

Feels like I can join the conversation. The interface and its features gain social and contextual meaning, through subtleties or bigger movements. As a designer, I can have a critical look at how these interfaces are built.

Who can help you and how?

Marloes de Valk, because of her knowledge on persuasive design, especially with the connection with Impakt festival. The Impakt festival itself can stimulate my research. The programme for this year is called Speculative Interfaces and it will investigate the interaction and relationship between technology and humans, and how this relationship can alter behaviours. I will attend two days of the festival.

Past Xpub students like Lucia Dossin and Lídia Pereira, which have work on similar topics.

Joana Moll and Femke Snelting, with the connection with Critical Interface Politics. This year-long research is full of useful resources. Includes the Critical Interface Toolbox and also related to the Interface Manifesto.

Olia Lialina, an artist with a lot of work on web interfaces. I will be in her workshop in November, which explores early web pages through the interface of The GeoCities archive. Approximately 382,000 home pages.

Xpub staff and students, for the variety of useful input.

Relation to previous practice

I understand that design shapes our ability to access, participate in, and contribute to the world (Holmes, 2018). As a graphic designer myself, I always was interested in the biases I implement in the things I build. Especially when those determine who can engage and how they do it.

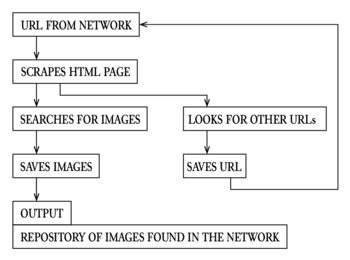

Last year we discussed decentralised networks on Special Issue 8: The Network We (de)Served, and this build up my interest in the subject. I understood how creating new platforms and looking for alternatives reveals the desire for bottom-up changes and more active end-users. It became clear that centralised models of technology propagate limited ideas, and those ideas shape our society. As a project for that same Special Issue, I prototyped some tools that helped me visualize the ideas I was discussing. To turn the research into tools is something that I intend to continue for this final project.

Relation to a larger context

The urge to take control of our online spaces reveals the present concern over software pervasiveness, automation and accountability. Software is found on diverse objects and systems but is not always perceptible or understandable. In this way, software studies try to open the black box, looking for its methods and routines. (Kitchin and Dodge, 2011) However, opening the black box is not enough. Information without context, processing and analysing, is not accessible to the users. Furthermore, demanding transparency from big social media platforms doesn't provide the agency we seek as the ability to see doesn't mean the power to govern it. (Ananny and Crawford, 2016) At the same time, the increasing automation of our systems means even less control and less accountability.

To overcome these difficulties, it makes sense to get around the software and focus on the relationship between the system and its users. Several projects work to visualise data, as a method for understanding relevant connections. Projects such as Ad.watch which compiles and visualises datasets of political ads on Facebook and Instagram to display the dubious relations between politics and social media platforms. Other projects decide to engage with the interface itself. Through plugins, add-ons, small robots and DIY techniques. Some authors encourage resistance arguing for alternative design practices through glitches, imperfect features, disturbing or illogical processes. (Hollanek, 2019)

All these strategies support more user agency. As social media platforms become ubiquitous, spreading its convictions to billions of people, it is important to amplify these movements outside the tech world. It only makes sense to be part of a community that makes use of platforms in their own terms.

ad.watch compiles and visualises datasets of political ads on Facebook and Instagram. This screenshot shows the activity of my city in Portugal. The political party that created controversial street billboards aimed at young people is also the biggest investor in social media advertising.

References

Ananny, M. and Crawford, K. (2018) Seeing without knowing: Limitations of the transparency ideal and its application to algorithmic accountability. New Media & Society, 20 (3): 973–989.

Century of the Self (2002) Film. Adam Curtis. England, BBC.

DNL# 13: HATE NEWS. Keynote with Andrea Noel and Renata Avila (2018) Film.

Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l2z6jP0Ynwg&list=PLmm_HP_Sb_cTFwQrgkRvP8yqJqerkttpm&index=3 (Accessed: 12 November 2019).

Dubrofsky, R.E. and Magnet, S. (2015) Feminist surveillance studies. Durham: Duke University Press, 221–228.

Hollanek, T. (2019) Non-user-friendly. Staging resistance with interpassive user experience design. APRJA, 8, 184–193

Holmes, K. and Maeda, J. (2018) Mismatch: how inclusion shapes design. Simplicity : design, technology, business, life. Cambridge, Massachusetts ; London, England: The MIT Press.

Ingraham, C. and Reeves, J. (2016) New media, new panics. Critical Studies in Media Communication, 33 (5): 455–467.

Kitchin, R. and Dodge, M. (2011) Code/space: software and everyday life. Software studies. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 3-21.

Lialina, O. (2018) Once Again, The Doorknob. On Affordance, Forgiveness and Ambiguity in Human Computer and Human Robot Interaction.

Available at: http://contemporary-home-computing.org/affordance/ (Accessed: 17 September 2019).

Shaw, T. (2017) Invisible Manipulators of Your Mind., 20 April.

Available at: https://www.nybooks.com/articles/2017/04/20/kahneman-tversky-invisible-mind-manipulators/ (Accessed: 11 November 2019).

Williams, J. (2018) Stand out of our light: freedom and resistance in the attention economy. Cambridge, United Kingdom ; New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Winner, L. (1980) Do Artifacts Have Politics? Daedalus, 109(1), 121–136