User:Alice/Chapter draft: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| (54 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

=Chapter outline= | =Chapter outline= | ||

What is the current situation regarding food technologies? How has food become an issue viewed as an engineering problem that needs to be solved? And what is the goal towards which current technologies are aspiring? | |||

'''Point A''' | '''Point A''' | ||

| Line 20: | Line 20: | ||

=Research focus= | =Research focus= | ||

Making connections between food and technology | Making connections between food and technology beyond the lens of techno-idealism and discussing the impact of technology on our current/future realities. | ||

=Premise= | =Premise= | ||

Inspired by the book 'In the age of the smart machine' by Shoshana Zuboff, I think it is interesting to look at the meal replacement phenomenon as potentially similar to the computerization of the workplace. What | Inspired by the book 'In the age of the smart machine' by Shoshana Zuboff, I think it is interesting to look at the meal replacement phenomenon as potentially similar to the computerization of the workplace (Zuboff, 1988). What if it does become the future of food? What can we learn today, on the possible brink of a crucial development, ahead of tech innovations that will potentially change the way we live as humans and relate to our bodies? | ||

=Summary= | |||

The aim of this chapter is to discuss the current and future implications of technology in food. Being faced with immense possibilities in technology, as well as massive new challenges related to changes in climate, what can we do today in anticipation of a radically different food future? | |||

= | =Introduction= | ||

Inspired by the book 'In the age of the smart machine' by Shoshana Zuboff, I think it is interesting to look at the meal replacement phenomenon as potentially similar to the computerization of the workplace. What are the potential implications if it does indeed become the future of food? What can we learn today, on the possible brink of a crucial development, ahead of tech innovations that will potentially change the way we live as humans and relate to our bodies? | |||

My | My research on food discourse in current tech practices started from a bad feeling. How come food is so present as a form of experimentation in hacker culture? Why has it become such a big part of their discourse? Why are so many new Silicon Valley companies receiving VC money for food innovation? And what parts of food culture are being lost in this process? | ||

== | = Point A - appropriated terminology = | ||

==What is appropriation== | |||

The official definition of cultural appropriation is 'the act of taking or using things from a culture that is not your own, especially without showing that you understand or respect this culture' (Cambridge Dictionary) or 'The unacknowledged or inappropriate adoption of the customs, practices, ideas, etc. of one people or society by members of another and typically more dominant people or society.' (Oxford dictionary) | |||

I argue that the transfer of terminology, on a smaller scale, and the innovations in food technology on a larger scale are instances of cultural appropriation. | |||

[[File:All work.jpg|150px|frameless|left|Wages for housework]] | |||

In the case of the current representations of food in society, I noticed a couple of trends that have certain aspects of cultural appropriation. On a broader scale, I can mention the representation of men and women in food culture, especially in popular culture. Women's attempts to make cooking and domestic activities recognized as a legitimate occupation have been largely overwritten by the new status symbol given to chefs, male in their majority, around the world. But this issue is not the focus of this chapter. | |||

In food technology, there has been a clear rebranding of products intended for women, such as the weight loss meal replacement Slimfast, into a product meant for busy, successful businessmen (Bowles, 2016). On the same note, cultural/spiritual traditions such as fasting (Tiku, 2016), doping for athletes with nootropics and other enhancement drugs (Bloomberg, 2016), or appropriated traditional recipes rebranded as proprietary innovations (Bulletproof, 2016) are all familiar in Silicon Valley. | |||

[[File:Idea_bulletproof.png|300px|frameless|center|Getting good ideas]] | |||

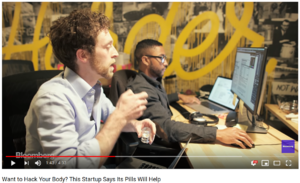

Not surprisingly, the 'new and improved' food industry that comes from Silicon Valley is overwhelmingly male. Their success model is based on self-experimentation, a habit that extends to the employees of the company. For instance, all HVMAN employees do intermittent fasting and constantly seem to be taking pills at their desks, even though the founders claim the habit is not forced upon the employees. | |||

[[File:Hvmn.png|300px|frameless|right|HVMN co-founder popping pills at his desk]] | |||

==Cooking as programming== | |||

I have not been able to find the starting point of the food terminology being used in the programming world, but my first introduction to it was through the O'Reilly collection of cookbooks. It seems that programmers are quite fond of this analogy, something that can be seen, for instance, in the foreword for the O'Reilly Perl Cookbook, written by Larry Wall. While, in his opinion, 'Cooking is the humblest of arts', and both cooking and programming languages, with a little bit of creativity, can be used 'not merely (for) getting the job done, but doing so in a way that makes your journey through life a little more pleasant' (Wall in Christiansen & Torkington, 1998). One of the nicest things he has to say within this analogy is the hope that Perl recipes will be passed on to future generations, much like traditional recipes written by grandmothers in old, dusty handwritten cookbooks. | |||

[[File:Pythoncookbook.jpg|200px|frameless|left|Cookbooks are not for everybody]] | |||

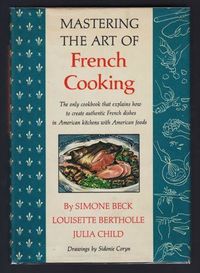

[[File:Julia.JPG|200px|frameless|right|Cooking is an art]] | |||

While the previous example is bound to give all programmers a warm and fuzzy feeling, there are plenty other encounters in the tech world. On the one hand, there is a tendency to idealize the figure of the geek, the nerd, the misunderstood genius who prefers to hack away at his computer rather than face the real world. The geek has integration issues outside of the geek community. Out there, the geek has trouble understanding the ways of the world. Portrayal of men (since the geek figure is always a man) as useless in the home, clumsy, inexperienced, only further reinforces the idea that it's the woman's role to stay on top of these domestic activities. Here's a telling example of this view: 'Hackers, makers, programmers, engineers, nerds, techies—what we’ll call “geeks” for the rest of the book (deal with it)—we’re a creative lot who don’t like to be told what to do. We’d rather be handed a box full of toys or random electronic components, or yarn, or whatever, and let loose to play. But something happens to some geeks when handed a boxful of spatulas, whisks, and sugar. Lockup. Fear. Foreign feelings associated with public speaking, or worse, coulrophobia.' (Potter, 2010) | |||

- | On the other hand, there is the tendency to explain programming and algorithms using cooking as an analogy. This oversimplification is nothing new in terms of pedagogic methods, but in this case it makes the assumption that everyone is accustomed, familiar and comfortable with cooking, which is often not the truth. In his book 'Algorithmic Adventures. From Knowledge to Magic', J. Hromkovic attempts for the entirety of the chapter 'Algorithmics, or What Have Programming and Baking in Common' to find similarities for all aspects of an algorithm in the cooking world. The definition if the algorithm is meant to bridge the gap: 'an algorithm (a method) provides simple and unambiguous advice on how to proceed step by step in order to reach our goal.' (Hromovic, 2009). However, throughout the rest of the chapter, I found the analogies more and more forced, making the entire explanation more confusing than it was intended. In another example, the author is quick to note that 'Programmers are the master chefs of the computing world - except the recipes they invent don't just give us a nice meal, they change the way we live.' His claim seems to be: the two are similar, but, of course, cooking is infinitely more trivial than programming, because the latter has lifechanging capacities. | ||

- | In the world of highly personalized nutrition, developed from medical use to a type of entrepreneurial lifestyle, the recipe has been reduced to a spreadsheet. In the hope that it will make life easier and more efficient, complete food enthusiasts have gathered on an online platform to share their extremely technical recipes for meal replacements, with ingredients measured down to a single gram, and a link that can take you straight to a checkout basket on Amazon. You can add tasty ingredients such as potassium chloride, grass-fed whey and choline bitartrate to your fresh batch of DIY powder, ready to be mixed with water and enjoyed for every meal. In real life, this approach to consumption has several issues - from the obscuring of food production, to over-reliance on corporations for sustenance. <span style="color:hotpink"> '''Add more info here''' </span> | ||

==Issues related to current food tech practices== | |||

Current food technologies, such as meal replacements, make promises for an empowered self, with full control over what they put in their own body. The claim is that ingesting a bit of potassium is more efficient than eating a banana. But the process of producing the ingredients is never exposed, thus further obscuring the processes involved in food production. | |||

Biohacking comes from the view that the body is simply another machine we can hack into (especially with the new CRISPR and genome identification technologies). This view is repeated over and over again by founders of various life-improving brain-enhancing death-repealing companies. The examples are many: ‘‘You monitor and manage the human body and then do small-level system upgrades. [...] Before you do a hardware upgrade, shouldn’t you make better use of the hardware you have right now?’’ (Wortham, 2015). | |||

The celebration of not having time to tend to your bodily needs properly, and at the same time putting so much emphasis on giving the body personalized nutrition in the most pleasureless way is, of course, a paradox. At the same time, the idea that you are solely responsible for your well-being, and that you can control your health and efficiency with the right consumer habits is another heavily promoted idea. Startups in Silicon Valley and all over the world are more than ready to provide products to any imaginable issue that can be identified, in order to achieve a desirable level of quality of life. This is problematic in many ways, because it completely ignores other factors that influence our lives, such as social class, income, education, access etc, as well as promoting efficiency and production as the main goals to be achieved by humans. | |||

the | =Disconnecting the mind from the body= | ||

==Meal replacements== | |||

The | The way we transform nature for our personal purpose does change the way we interact with each other and with the world. Developments in food production are changing the way we relate to the world. I started my research with the idea that meal replacements are the materialization of the male-dominated tech industry taking over nutrition and care for the human body. But there was always an underlying feeling that it has to be bigger than that. | ||

I | In my research of meal replacements I looked at the development and rise of Soylent. The product was developed in Silicon Valley by a couple of computer scientists who were looking for their breakthrough in the startup world. They were all young white males with no experience with cooking, who were allegedly surviving on frozen fast food, and were frustrated by the quality of their meals and the time it took away from their day (Widdicombe, 2014). Taking the approach of an engineer to this problematic situation, they came to the conclusion that traditional nutrition is very inefficient, that food is not the best way to transfer the necessary nutrients for the survival of the body. The best way to go about this, according to them, is by reducing food to its most basic elements. In my interpretation, this represents the ultimate life hack, as it allows them to further release themselves from their human bodily needs and exist purely for the purpose of being efficient in their search for profit. In this way, the only food preparation and consumption necessary on a daily basis is reduced to a minimum. | ||

I | [[File:Soylent2.png|300px|frameless|center|Mantra]] | ||

A surprising twist that I have noticed within the community of meal replacement enthusiasts is the desire to get involved in the process creating their meals. The website completefoods.co, a kind of food-related GitHub, is a place where the complete food enthusiasts post their recipes and have discussions on various versions of those recipes. This desire is influenced by the increasing volume of nutritional information coming from various sources that we are exposed to constantly (Dolejsova, 2016). | |||

==Focus on nutrients rather than food== | |||

Nutritionism is the basis of all iterations of products trying to 'disrupt mealtimes'. As expressed by Huel's community manager, 'We wanted to strip it back to what the actual purpose of food is – to provide nutrition (...) People are very focused on taste now – does it taste good? That is not the primary purpose of food' (Turk, 2018). | |||

Nutritionism and the food industry in general have, for decades, capitalized on people's fears and confusion related to food. 'Nutrients—those chemical compounds and minerals in foods that scientists have identified as important to our health—gleamed with the promise of scientific certainty. Eat more of the right ones, fewer of the wrong, and you would live longer, avoid chronic diseases, and lose weight' (Pollan, 2008). | |||

[[File:Vitamins1.jpg|200px|frameless|right|Fortified donuts]] | |||

Today's companies which produce and sell meal replacements and other food innovations all have a number of health claims, including complete nutrition, better concentration, prevention of diabetes, etc. But the lack of unaffiliated scientific studies, especially long-term (nonexistent), and the association with nutritionists that sit on the board of directors and make dubious health claims can make anyone more than a little bit suspicious of these products. The fact that the food industry is able to make such claims can be traced back to the 90s, when the US Congress passed a couple of laws (FDAMA and DSHEA) which gave more freedom to the food and supplements industries to introduce new substances into their products without much push back from the FDA. (Nestle, 2013) | |||

Looking at food as simply fuel for the body means completely disregarding the entire culture that has grown around food in every part of society. This phenomenon is described by Marion Nestle as reductionism, which, in her view, means reducing food to containers of nutrients. 'Techno-foods offer a reductionist approach to choosing a healthful diet'(Nestle, pp 334) which only encourages food producers to come up with more and more products to sell to those who find this view appealing. 'Jean-Anthelme Brillat-Savarin, the eighteenth-century gastronomic, drew a useful distinction between the alimentary activity of animals, which "feed," and humans, who eat, or dine, a practice, he suggested, that owes as much to culture as it does to biology' (Pollan, 2008). | |||

= | ==Efficiency, body discipline and the road to conquering death== | ||

Among the latest trends in the mainstream technology world, I identified 'meal disruption', genomics, 'the quantified self', nootropics and geriatrics. The wish to disconnect the weakness of the body from the sharpness of the mind is present in all these iterations of technology. In the view of Ray Kurzweil, for instance, the body deserves no respect in its fragility, and all its shortcomings can be conquered through the intelligence of the brain. In the future he envisions and predicts, a transhumanist future, the body as an unique physical entity has no place, when our minds will be able to explore many new worlds and inhabit virtual bodies, while holding vast amounts of universal knowledge. This view is in clear contradiction to feminist view on situated knowledge. | |||

I' | |||

“We seek not the knowledges ruled by phallogocentrism (nostalgia for the presence of the one true Word) and disembodied vision. We seek those ruled by | |||

partial sight and limited voice - not partiality for its own sake but, rather, for the sake of the connections and unexpected openings situated | |||

knowledges make possible.” (Haraway, 1988). | |||

In recent years, more and more money and intelligence have been invested in Silicon Valley into studying the human body. The focus, as it seems, is not so much on curing diseases such as cancer and diabetes, but specifically on curing the one 'disease' affecting the entire population: growing old. The richest of the rich are deeply invested in making themselves live as much as possible. The most likely implication of this plan is that anti-ageing technologies will only be available to the elite, and will not benefit the rest of the world in any way. | |||

'Joon Yun, a doctor who runs a health-care hedge fund, announced that he and his wife had given the first two million dollars toward funding the challenge. “I have the idea that aging is plastic, that it’s encoded,” he said. “If something is encoded, you can crack the code. (...) If you can crack the code, you can hack the code!”' (Friend, 2017). In the same view, Google has started a whole new company surrounded by secrets, Calico, dedicated entirely to this purpose, also considered 'one of the first funders of transhumanism'. (Fuck off Google wiki) Ray Kurzweil, the billionaire genius, now Google employee, who takes about 100 different pills per day, also owns a company dedicated to selling overpriced vitamins for people who fear their aging bodies. | |||

===Transhumanism=== | |||

<span style="color:hotpink"> '''Transform into a mini chapter''' </span> | |||

Definition: 'The belief or theory that the human race can evolve beyond its current physical and mental limitations, especially by means of science and technology.' (Oxford dictionaries) | |||

How can we overcome our physical limitations, so that our minds can ascend to the Singularity? The ageing body, with its physical needs, is a problem that current tech biohacking companies are trying to solve. It is no surprise that Google Ventures is a big investor in health technology and it's one of the main investors for Soylent (and some other food tech companies). I believe meal replacements and current food technologies are just incipient steps towards the idea of the singularity, promoted by Ray Kurzweil. Ray himself is living on a diet of around 100 pills per day, a very complex version of DIY Soylent that is meant to keep him alive as long as possible. | |||

But this imagined future was never meant to be for everybody. 'While people of color, trans folks and the poor struggle to live within the timespan they’re allegedly already allotted by virtue of living in an industrialized nation, a handful of powerful white guys promote themselves as humanitarians for trying to extend the already long lives of the favored few. There aren’t many futures more chilling to me than one in which not even the march of time can free us from our oligarchs' (Shane, 2016). | |||

=References= | =References= | ||

Anonymous (n.d.) In CS4F. Available at http://www.cs4fn.org/programming/recipeprogramming.php | |||

Christiansen, T., Torkington, N. (1998) ''Perl Cookbook''. Sebastopol, CA:O'Reilly | |||

Cultural appropriation. (n.d.) In: ''Cambridge Advanced Learner's Dictionary & Thesaurus'' [online] Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Available at: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/cultural-appropriation [Accessed 07.12.2018] | |||

Cultural Appropriation. (n.d.) In: ''Oxford Dictionaries'' [online] Oxford: Oxford University Press . Available at: https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/cultural_appropriation [Accessed 07.12.2018] | |||

Dolejsova, M. (2016) Deciphering a Meal Through Open Source Standards: Soylent and the Rise of Diet Hackers. In: ''alt.chi''. San Jose:CHI 2016. | |||

Friend, T. (2017) Silicon Valley's Quest to Live Forever. ''The New Yorker'', [online]. Available at https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2017/04/03/silicon-valleys-quest-to-live-forever. [Accessed 28.11.2018] | |||

Gowles, N. (2016)Food Tech Is Just Men Rebranding What Women Have Done for Decades. ''The Guardian'', [online]. Available at https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2016/apr/01/food-technology-soylent-slimfast-juice-fasting [Accessed 05.12.2018] | |||

Haraway, D. (1988) Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial | |||

Perspective. ''Feminist Studies'', Vol. 14(3), pp. 575-599 | |||

Hromovic, J. (2009) ''Algorithmic Adventures. From Knowledge to Magic''. Berlin Heidelberg:Springer Verlag | |||

Nestle, M. (2013) ''Food Politics: How the Food Industry Influences Nutrition and Health, 3rd Edition''. Berkley: University of California Press | |||

Pollan, M. (2008) ''In Defense of Food. An Eater's Manifesto''. New York:Penguin Press | Pollan, M. (2008) ''In Defense of Food. An Eater's Manifesto''. New York:Penguin Press | ||

Potter, J. (2010) ''Cooking for Geeks: Real Science, Great Hacks, and Good Food''. Sebastopol, CA: O'Reilly Media | |||

Shane, C. (2016) Life extension technology gives us a bleak future: more white men. ''Splinternews'', [online]. Available at: https://splinternews.com/life-extension-technology-gives-us-a-bleak-future-more-1793857274 [Accessed 06.12.2018] | |||

Sharma, S. (2018) Going to Work in Mommy's Basement. ''Boston Review'', [online]. Available at http://bostonreview.net/gender-sexuality/sarah-sharma-going-work-mommys-basement [Accessed 05.01.2019] | |||

Tiku, N. (2016)Startup Workers Say No to Free Food, Hell Yeah to Intermittent Fasting. ''Buzzfeed News'', [online]. Available at https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/nitashatiku/intermittent-fasting [Accessed 05.12.2018] | |||

Turk, V. (2018) Powdered Food is Back Again to Take on Sandwiches and Cereal. ''Wired'', [online]. Available at: https://www.wired.co.uk/article/huel-liquid-food-replacement-new-flavours [Accessed 05.12.2018] | |||

Widdicombe, L. (2014) The End of Food. ''The New Yorker'' [online]. Available at: https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2014/05/12/the-end-of-food [Accessed 07.12.2018] | |||

Wortham, J. (2016) You, Only Better. ''New York Times'', [online]. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2015/11/15/magazine/you-only-better.html [Accessed 07.12.2018] | |||

Zuboff, S. (1988) ''In the Age of the Smart Machine'', Basic Books | |||

Latest revision as of 15:34, 5 January 2019

Chapter outline

What is the current situation regarding food technologies? How has food become an issue viewed as an engineering problem that needs to be solved? And what is the goal towards which current technologies are aspiring?

Point A

The recipe is often used as metaphor for computer programs.

Programmers have been appropriating food terminology

Programming and computer engineering has often been explained through the metaphor of cooking, sometimes in a patronizing way

Point B

Food and nutrition are viewed as an engineering problem that can be solved through technology. Our humanity is slowing us down from accumulating capital, which is why this problem needs to be eliminated.

Advances in food technology have pushed people even further away from the natural world

The rise of food startups, meal substitutes, biohacking, and engineered/personalized nutrition are all symptoms of a while male appropriation of food culture.

Research focus

Making connections between food and technology beyond the lens of techno-idealism and discussing the impact of technology on our current/future realities.

Premise

Inspired by the book 'In the age of the smart machine' by Shoshana Zuboff, I think it is interesting to look at the meal replacement phenomenon as potentially similar to the computerization of the workplace (Zuboff, 1988). What if it does become the future of food? What can we learn today, on the possible brink of a crucial development, ahead of tech innovations that will potentially change the way we live as humans and relate to our bodies?

Summary

The aim of this chapter is to discuss the current and future implications of technology in food. Being faced with immense possibilities in technology, as well as massive new challenges related to changes in climate, what can we do today in anticipation of a radically different food future?

Introduction

Inspired by the book 'In the age of the smart machine' by Shoshana Zuboff, I think it is interesting to look at the meal replacement phenomenon as potentially similar to the computerization of the workplace. What are the potential implications if it does indeed become the future of food? What can we learn today, on the possible brink of a crucial development, ahead of tech innovations that will potentially change the way we live as humans and relate to our bodies?

My research on food discourse in current tech practices started from a bad feeling. How come food is so present as a form of experimentation in hacker culture? Why has it become such a big part of their discourse? Why are so many new Silicon Valley companies receiving VC money for food innovation? And what parts of food culture are being lost in this process?

Point A - appropriated terminology

What is appropriation

The official definition of cultural appropriation is 'the act of taking or using things from a culture that is not your own, especially without showing that you understand or respect this culture' (Cambridge Dictionary) or 'The unacknowledged or inappropriate adoption of the customs, practices, ideas, etc. of one people or society by members of another and typically more dominant people or society.' (Oxford dictionary) I argue that the transfer of terminology, on a smaller scale, and the innovations in food technology on a larger scale are instances of cultural appropriation.

In the case of the current representations of food in society, I noticed a couple of trends that have certain aspects of cultural appropriation. On a broader scale, I can mention the representation of men and women in food culture, especially in popular culture. Women's attempts to make cooking and domestic activities recognized as a legitimate occupation have been largely overwritten by the new status symbol given to chefs, male in their majority, around the world. But this issue is not the focus of this chapter.

In food technology, there has been a clear rebranding of products intended for women, such as the weight loss meal replacement Slimfast, into a product meant for busy, successful businessmen (Bowles, 2016). On the same note, cultural/spiritual traditions such as fasting (Tiku, 2016), doping for athletes with nootropics and other enhancement drugs (Bloomberg, 2016), or appropriated traditional recipes rebranded as proprietary innovations (Bulletproof, 2016) are all familiar in Silicon Valley.

Not surprisingly, the 'new and improved' food industry that comes from Silicon Valley is overwhelmingly male. Their success model is based on self-experimentation, a habit that extends to the employees of the company. For instance, all HVMAN employees do intermittent fasting and constantly seem to be taking pills at their desks, even though the founders claim the habit is not forced upon the employees.

Cooking as programming

I have not been able to find the starting point of the food terminology being used in the programming world, but my first introduction to it was through the O'Reilly collection of cookbooks. It seems that programmers are quite fond of this analogy, something that can be seen, for instance, in the foreword for the O'Reilly Perl Cookbook, written by Larry Wall. While, in his opinion, 'Cooking is the humblest of arts', and both cooking and programming languages, with a little bit of creativity, can be used 'not merely (for) getting the job done, but doing so in a way that makes your journey through life a little more pleasant' (Wall in Christiansen & Torkington, 1998). One of the nicest things he has to say within this analogy is the hope that Perl recipes will be passed on to future generations, much like traditional recipes written by grandmothers in old, dusty handwritten cookbooks.

While the previous example is bound to give all programmers a warm and fuzzy feeling, there are plenty other encounters in the tech world. On the one hand, there is a tendency to idealize the figure of the geek, the nerd, the misunderstood genius who prefers to hack away at his computer rather than face the real world. The geek has integration issues outside of the geek community. Out there, the geek has trouble understanding the ways of the world. Portrayal of men (since the geek figure is always a man) as useless in the home, clumsy, inexperienced, only further reinforces the idea that it's the woman's role to stay on top of these domestic activities. Here's a telling example of this view: 'Hackers, makers, programmers, engineers, nerds, techies—what we’ll call “geeks” for the rest of the book (deal with it)—we’re a creative lot who don’t like to be told what to do. We’d rather be handed a box full of toys or random electronic components, or yarn, or whatever, and let loose to play. But something happens to some geeks when handed a boxful of spatulas, whisks, and sugar. Lockup. Fear. Foreign feelings associated with public speaking, or worse, coulrophobia.' (Potter, 2010)

On the other hand, there is the tendency to explain programming and algorithms using cooking as an analogy. This oversimplification is nothing new in terms of pedagogic methods, but in this case it makes the assumption that everyone is accustomed, familiar and comfortable with cooking, which is often not the truth. In his book 'Algorithmic Adventures. From Knowledge to Magic', J. Hromkovic attempts for the entirety of the chapter 'Algorithmics, or What Have Programming and Baking in Common' to find similarities for all aspects of an algorithm in the cooking world. The definition if the algorithm is meant to bridge the gap: 'an algorithm (a method) provides simple and unambiguous advice on how to proceed step by step in order to reach our goal.' (Hromovic, 2009). However, throughout the rest of the chapter, I found the analogies more and more forced, making the entire explanation more confusing than it was intended. In another example, the author is quick to note that 'Programmers are the master chefs of the computing world - except the recipes they invent don't just give us a nice meal, they change the way we live.' His claim seems to be: the two are similar, but, of course, cooking is infinitely more trivial than programming, because the latter has lifechanging capacities.

In the world of highly personalized nutrition, developed from medical use to a type of entrepreneurial lifestyle, the recipe has been reduced to a spreadsheet. In the hope that it will make life easier and more efficient, complete food enthusiasts have gathered on an online platform to share their extremely technical recipes for meal replacements, with ingredients measured down to a single gram, and a link that can take you straight to a checkout basket on Amazon. You can add tasty ingredients such as potassium chloride, grass-fed whey and choline bitartrate to your fresh batch of DIY powder, ready to be mixed with water and enjoyed for every meal. In real life, this approach to consumption has several issues - from the obscuring of food production, to over-reliance on corporations for sustenance. Add more info here

Current food technologies, such as meal replacements, make promises for an empowered self, with full control over what they put in their own body. The claim is that ingesting a bit of potassium is more efficient than eating a banana. But the process of producing the ingredients is never exposed, thus further obscuring the processes involved in food production.

Biohacking comes from the view that the body is simply another machine we can hack into (especially with the new CRISPR and genome identification technologies). This view is repeated over and over again by founders of various life-improving brain-enhancing death-repealing companies. The examples are many: ‘‘You monitor and manage the human body and then do small-level system upgrades. [...] Before you do a hardware upgrade, shouldn’t you make better use of the hardware you have right now?’’ (Wortham, 2015).

The celebration of not having time to tend to your bodily needs properly, and at the same time putting so much emphasis on giving the body personalized nutrition in the most pleasureless way is, of course, a paradox. At the same time, the idea that you are solely responsible for your well-being, and that you can control your health and efficiency with the right consumer habits is another heavily promoted idea. Startups in Silicon Valley and all over the world are more than ready to provide products to any imaginable issue that can be identified, in order to achieve a desirable level of quality of life. This is problematic in many ways, because it completely ignores other factors that influence our lives, such as social class, income, education, access etc, as well as promoting efficiency and production as the main goals to be achieved by humans.

Disconnecting the mind from the body

Meal replacements

The way we transform nature for our personal purpose does change the way we interact with each other and with the world. Developments in food production are changing the way we relate to the world. I started my research with the idea that meal replacements are the materialization of the male-dominated tech industry taking over nutrition and care for the human body. But there was always an underlying feeling that it has to be bigger than that.

In my research of meal replacements I looked at the development and rise of Soylent. The product was developed in Silicon Valley by a couple of computer scientists who were looking for their breakthrough in the startup world. They were all young white males with no experience with cooking, who were allegedly surviving on frozen fast food, and were frustrated by the quality of their meals and the time it took away from their day (Widdicombe, 2014). Taking the approach of an engineer to this problematic situation, they came to the conclusion that traditional nutrition is very inefficient, that food is not the best way to transfer the necessary nutrients for the survival of the body. The best way to go about this, according to them, is by reducing food to its most basic elements. In my interpretation, this represents the ultimate life hack, as it allows them to further release themselves from their human bodily needs and exist purely for the purpose of being efficient in their search for profit. In this way, the only food preparation and consumption necessary on a daily basis is reduced to a minimum.

A surprising twist that I have noticed within the community of meal replacement enthusiasts is the desire to get involved in the process creating their meals. The website completefoods.co, a kind of food-related GitHub, is a place where the complete food enthusiasts post their recipes and have discussions on various versions of those recipes. This desire is influenced by the increasing volume of nutritional information coming from various sources that we are exposed to constantly (Dolejsova, 2016).

Focus on nutrients rather than food

Nutritionism is the basis of all iterations of products trying to 'disrupt mealtimes'. As expressed by Huel's community manager, 'We wanted to strip it back to what the actual purpose of food is – to provide nutrition (...) People are very focused on taste now – does it taste good? That is not the primary purpose of food' (Turk, 2018). Nutritionism and the food industry in general have, for decades, capitalized on people's fears and confusion related to food. 'Nutrients—those chemical compounds and minerals in foods that scientists have identified as important to our health—gleamed with the promise of scientific certainty. Eat more of the right ones, fewer of the wrong, and you would live longer, avoid chronic diseases, and lose weight' (Pollan, 2008).

Today's companies which produce and sell meal replacements and other food innovations all have a number of health claims, including complete nutrition, better concentration, prevention of diabetes, etc. But the lack of unaffiliated scientific studies, especially long-term (nonexistent), and the association with nutritionists that sit on the board of directors and make dubious health claims can make anyone more than a little bit suspicious of these products. The fact that the food industry is able to make such claims can be traced back to the 90s, when the US Congress passed a couple of laws (FDAMA and DSHEA) which gave more freedom to the food and supplements industries to introduce new substances into their products without much push back from the FDA. (Nestle, 2013)

Looking at food as simply fuel for the body means completely disregarding the entire culture that has grown around food in every part of society. This phenomenon is described by Marion Nestle as reductionism, which, in her view, means reducing food to containers of nutrients. 'Techno-foods offer a reductionist approach to choosing a healthful diet'(Nestle, pp 334) which only encourages food producers to come up with more and more products to sell to those who find this view appealing. 'Jean-Anthelme Brillat-Savarin, the eighteenth-century gastronomic, drew a useful distinction between the alimentary activity of animals, which "feed," and humans, who eat, or dine, a practice, he suggested, that owes as much to culture as it does to biology' (Pollan, 2008).

Efficiency, body discipline and the road to conquering death

Among the latest trends in the mainstream technology world, I identified 'meal disruption', genomics, 'the quantified self', nootropics and geriatrics. The wish to disconnect the weakness of the body from the sharpness of the mind is present in all these iterations of technology. In the view of Ray Kurzweil, for instance, the body deserves no respect in its fragility, and all its shortcomings can be conquered through the intelligence of the brain. In the future he envisions and predicts, a transhumanist future, the body as an unique physical entity has no place, when our minds will be able to explore many new worlds and inhabit virtual bodies, while holding vast amounts of universal knowledge. This view is in clear contradiction to feminist view on situated knowledge.

“We seek not the knowledges ruled by phallogocentrism (nostalgia for the presence of the one true Word) and disembodied vision. We seek those ruled by partial sight and limited voice - not partiality for its own sake but, rather, for the sake of the connections and unexpected openings situated knowledges make possible.” (Haraway, 1988).

In recent years, more and more money and intelligence have been invested in Silicon Valley into studying the human body. The focus, as it seems, is not so much on curing diseases such as cancer and diabetes, but specifically on curing the one 'disease' affecting the entire population: growing old. The richest of the rich are deeply invested in making themselves live as much as possible. The most likely implication of this plan is that anti-ageing technologies will only be available to the elite, and will not benefit the rest of the world in any way.

'Joon Yun, a doctor who runs a health-care hedge fund, announced that he and his wife had given the first two million dollars toward funding the challenge. “I have the idea that aging is plastic, that it’s encoded,” he said. “If something is encoded, you can crack the code. (...) If you can crack the code, you can hack the code!”' (Friend, 2017). In the same view, Google has started a whole new company surrounded by secrets, Calico, dedicated entirely to this purpose, also considered 'one of the first funders of transhumanism'. (Fuck off Google wiki) Ray Kurzweil, the billionaire genius, now Google employee, who takes about 100 different pills per day, also owns a company dedicated to selling overpriced vitamins for people who fear their aging bodies.

Transhumanism

Transform into a mini chapter

Definition: 'The belief or theory that the human race can evolve beyond its current physical and mental limitations, especially by means of science and technology.' (Oxford dictionaries)

How can we overcome our physical limitations, so that our minds can ascend to the Singularity? The ageing body, with its physical needs, is a problem that current tech biohacking companies are trying to solve. It is no surprise that Google Ventures is a big investor in health technology and it's one of the main investors for Soylent (and some other food tech companies). I believe meal replacements and current food technologies are just incipient steps towards the idea of the singularity, promoted by Ray Kurzweil. Ray himself is living on a diet of around 100 pills per day, a very complex version of DIY Soylent that is meant to keep him alive as long as possible.

But this imagined future was never meant to be for everybody. 'While people of color, trans folks and the poor struggle to live within the timespan they’re allegedly already allotted by virtue of living in an industrialized nation, a handful of powerful white guys promote themselves as humanitarians for trying to extend the already long lives of the favored few. There aren’t many futures more chilling to me than one in which not even the march of time can free us from our oligarchs' (Shane, 2016).

References

Anonymous (n.d.) In CS4F. Available at http://www.cs4fn.org/programming/recipeprogramming.php

Christiansen, T., Torkington, N. (1998) Perl Cookbook. Sebastopol, CA:O'Reilly

Cultural appropriation. (n.d.) In: Cambridge Advanced Learner's Dictionary & Thesaurus [online] Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Available at: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/cultural-appropriation [Accessed 07.12.2018]

Cultural Appropriation. (n.d.) In: Oxford Dictionaries [online] Oxford: Oxford University Press . Available at: https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/cultural_appropriation [Accessed 07.12.2018]

Dolejsova, M. (2016) Deciphering a Meal Through Open Source Standards: Soylent and the Rise of Diet Hackers. In: alt.chi. San Jose:CHI 2016.

Friend, T. (2017) Silicon Valley's Quest to Live Forever. The New Yorker, [online]. Available at https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2017/04/03/silicon-valleys-quest-to-live-forever. [Accessed 28.11.2018]

Gowles, N. (2016)Food Tech Is Just Men Rebranding What Women Have Done for Decades. The Guardian, [online]. Available at https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2016/apr/01/food-technology-soylent-slimfast-juice-fasting [Accessed 05.12.2018]

Haraway, D. (1988) Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective. Feminist Studies, Vol. 14(3), pp. 575-599

Hromovic, J. (2009) Algorithmic Adventures. From Knowledge to Magic. Berlin Heidelberg:Springer Verlag

Nestle, M. (2013) Food Politics: How the Food Industry Influences Nutrition and Health, 3rd Edition. Berkley: University of California Press

Pollan, M. (2008) In Defense of Food. An Eater's Manifesto. New York:Penguin Press

Potter, J. (2010) Cooking for Geeks: Real Science, Great Hacks, and Good Food. Sebastopol, CA: O'Reilly Media

Shane, C. (2016) Life extension technology gives us a bleak future: more white men. Splinternews, [online]. Available at: https://splinternews.com/life-extension-technology-gives-us-a-bleak-future-more-1793857274 [Accessed 06.12.2018]

Sharma, S. (2018) Going to Work in Mommy's Basement. Boston Review, [online]. Available at http://bostonreview.net/gender-sexuality/sarah-sharma-going-work-mommys-basement [Accessed 05.01.2019]

Tiku, N. (2016)Startup Workers Say No to Free Food, Hell Yeah to Intermittent Fasting. Buzzfeed News, [online]. Available at https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/nitashatiku/intermittent-fasting [Accessed 05.12.2018]

Turk, V. (2018) Powdered Food is Back Again to Take on Sandwiches and Cereal. Wired, [online]. Available at: https://www.wired.co.uk/article/huel-liquid-food-replacement-new-flavours [Accessed 05.12.2018]

Widdicombe, L. (2014) The End of Food. The New Yorker [online]. Available at: https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2014/05/12/the-end-of-food [Accessed 07.12.2018]

Wortham, J. (2016) You, Only Better. New York Times, [online]. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2015/11/15/magazine/you-only-better.html [Accessed 07.12.2018]

Zuboff, S. (1988) In the Age of the Smart Machine, Basic Books